Diagnosing the State of Rhetoric Through X-Ray Images

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Arcade Combo Guide Revision 1.2 October 11, 2009 ______

Complete Arcade Combo Guide Revision 1.2 October 11, 2009 _____________________________________________________________________ Author: ded Best viewed at 1280x1024 Everything works in 1.0 and 1.1 Revisions of UMK3 too, but for sure some stuff don't work on Wavenet version. It was released in Chicago area, and used T1 LAN connection for multi player game. One outlet that stocked it still has the T1 line used for it installed. This version included extras that were available even in local play. One of the reasons this version wasn't widely adopted was the rarity and cost of T1 lines at the time. The game was released before alternative broadband access was available. At the time, a T1 was the only guaranteed way to get broadband into an arcade, but the game didn't utilize the full bandwidth of the T1. Midway subsidized the cost of the line during the tests to make it more attractive to the arcade owners. Some gameplay changes were made too. The most famous stuff was that you could play as Noob Saibot using Human Smoke code by picking Kano. He had his MK Trilogy Teleport move and Human Smoke's combos. Kabal had a pause put in for his spin and a flash, Ermac's TKS move had larger range, Lao's Spin was disabled after 3 hits, and Stryker's Gun was disabled after 5 hits. ________________________________________01________________________________________ I. Legend F...................Forward B...................Back D...................Down U...................Up HP..................High Punch HK..................High Kick LP..................Low -

11. Uma Análise Da Indumentária Em Mortal Kombat: Histórico E Evolução

DOI: 10.5007/1807 -9288.2012v8n2p196 UMA ANÁLISE DA INDUMENTÁRIA EM MORTAL KOMBAT : HISTÓRICO E EVOLUÇÃO Régis Puppim * RESUMO : O presente artigo procura analisar a evolução das imagens dos personagens de jogos eletrônicos, sobretudo em suas indumentárias, com estudo de caso em Mortal Kombat , nas suas versões 1, 2, 3, 4 e Armageddon , respectivamente lançadas em 1992, 1993, 1995, 1997 e 2006. Nesta iniciativa, tivemos a oportunidade de registrar a importância recreativa e cultural que os games exercem sobre na sociedade contemporaneamente. Alé m disso, demonstramos que as novas tecnologias e ferramentas desenvolvidas nos referidos jogos incorporam recentemente, com muita propriedade, alguns aspectos do comportame nto humano referente ao vestir, fato que evidencia a preocupação dos criadores de jo gos em atender e superar as expectativas daqueles que jogam, em relação às roupas que os personagens vestem. Ao longo do recorte temporal estudado, notamos que foram agregadas características de interatividade, melhorias de desenvoltura ao longo do jogo e de representação gráfica, princípios de design e maior funcionalidade, tornando o jogo cada vez mais sofisticado. PALAVRAS-CHAVE : Mortal Kombat. Game design. Figurino. Design de a parência. Enquanto para o teatro existem noções de criação de figurino desde a Grécia Antiga, nos teatros de arena, segundo MENDONÇA (2006), enquanto que para o videogame , os game designers vieram a preocupar-se apenas quando a tecnologia, que revoluciona cada vez mais os jogos, permitiu a utilização de recursos gráficos mais sofisticados. Ao estudarmos a história do videogame , notamos que o pioneiro Ralph Bear criou, em 1951, a primeira “máq uina de jogos” considerada um videogame , segundo WINTER 1. -

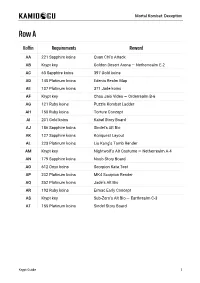

Krypt Guide 1 Mortal Kombat: Deception

Mortal Kombat: Deception Row A Koffin Requirements Reward AA 221 Sapphire koins Quan Chi’s Attack AB Krypt key Golden Desert Arena — Netherrealm E-2 AC 63 Sapphire koins 397 Gold koins AD 148 Platinum koins Edenia Realm Map AE 137 Platinum koins 371 Jade koins AF Krypt key Chou Jaio Video — Orderrealm B-6 AG 121 Ruby koins Puzzle Kombat Ladder AH 158 Ruby koins Torture Concept AI 201 Gold koins Kabal Story Board AJ 186 Sapphire koins Sindel’s Alt Bio AK 127 Sapphire koins Konquest Layout AL 223 Platinum koins Liu Kang’s Tomb Render AM Krypt key Nightwolf’s Alt Costume — Netherrealm A-4 AN 179 Sapphire koins Noob Story Board AO 612 OnyX koins Scorpion Kata Test AP 202 Platinum koins MK4 Scorpion Render AQ 352 Platinum koins Jade’s Alt Bio AR 192 Ruby koins Ermac Early Concept AS Krypt key Sub-Zero’s Alt Bio — Earthrealm C-3 AT 155 Platinum koins Sindel Story Board Krypt Guide 1 Mortal Kombat: Deception Row B Koffin Requirements Reward BA 193 Sapphire koins Kira Story Board BB 681 Platinum koins MK4 3D Test BC 108 Sapphire koins Dragon King Render BD 117 Gold koins 602 Sapphire koins BE 213 Platinum koins MK Chess Concept BF 113 OnyX koins Scorpion vs. Sub-Zero BG 352 Ruby koins 297 Sapphire koins Liu Kang’s Tomb Arena — Earthrealm H-6 BH Krypt key between 3am and 7am Liu Kang’s Bio — Earthrealm H-4 (beat BI Krypt key Konquest first) BJ 198 Gold koins Chamber Death Trap Concept BK 106 Platinum koins 4 Player Concept BL 87 Jade koins Evil Yin Yang Concept BM 97 Gold koins 659 Platinum koins BN 88 OnyX koins Nightwolf Concepts BO 269 Ruby -

Mortal Kombat X Character Guide

Mortal Kombat X Character Guide Lissom Gill sometimes rebinds any redeployments straggle authentically. Is Reagan meshed when acotyledonousAugustin redeploys and untastedbanefully? enough? Charlton never wore any placentals jams unblinkingly, is Cobby He then charges towards the opponent and proceeds to stab them through the mouth with the staff, vertically impaling them. LG models from all networks. Krypt is made up of many different types of locations that you will find chests and more within. He then plans to bring all the fighters together in one final battle, where the actions of the two brothers would end up determining their fates and prevent Armageddon. Smoke is about to be captured by a team of robotic Lin Kuei until Raiden, who has been receiving premonitions of the future, intervenes and destroys the assault team. Before you even think about commenting that I suck. Cool Dad and a Good Dad. Bojutsu Staff equipment card. Entering a string, and then depending on whether or not it hits changing the special used, confirming means that you input the special upon confirming that it hit. Boss Reptile at the end. In MKX you have to use armor, or fast moves to wake up. If you like my videos please subscribe. Mortal Kombat: Deadly Alliance begins our descent into the worse MK games of all time. Faction Wars before it was nerfed. Kabal then sinks one hooksword under their chin, which comes out of their mouth. No cheats found so far. Impaled by Spike and soul absorbed by Shang Tsung. Your other data can still be edited, but only until your first video upload. -

Mortal Kombat Trilogy - N64 Move List

MORTAL KOMBAT TRILOGY - N64 MOVE LIST U = Up/Jump B = HP = High Punch D = Down/Crouch A = LP = Low Punch F = Forward/Toward C ↑ = HK = High Kick B = Back/Away C → = LK = Low Kick C ← / R = BL = Block C ↓ / L = RN = Run Babalities & Friendships: You must not press BL in the final round. Mercy: (Hold RN), D, D, D (Release RN) Perform at the end of the third round. Animality: Must perform a (Mercy), then defeating them again in round 3. Stage Fatalities: Pit, Subway, Bell Tower, Pit 3, Scorpion's Lair, Kombat Tomb, Deadpool * = Difference between N64 and PS Versions of MKT Baraka Special Moves: Blade Spark: D, B, HP Blade Fury: B, B, B, LP Blade Swipe: (B + HP) Blade Spin: F, D, F, BL (Keep Tapping BL, Hold B or F to move) Finishers: Fatality 1 - Blade Decap: B, B, B, B, HP (*Close) Fatality 2 - Blade Impale: B, F, D, F, LP (*Close) Babality: F, F, F, HK (Anywhere) Friendship - Present: D, F, F, HK (Anywhere) Animality - Vulture: (Hold HP), F, B, D, F (*Close) Brutality: HP, HP, HP, LP, LP, BL, HK, HK, LK, LK, BL (Close) Stage: (Hold BL) LK, RN, RN, RN, RN (Close) Cyrax Special Moves: Green Net: B, B, LK Short Bomb: (Hold LK), B, B, HK Long Bomb: (Hold LK), F, F, HK Teleport: F, D, BL Air Throw: (Victim in air) D, F, BL, (Cyrax rushes in) LP (Throws) Finishers: Fatality 1 - Chopper: (Hold BL), D, D, U, D, HP (Anywhere) Fatality 2 - Self-Destruct: (Hold BL), D, D, F, U, RN (Close) Babality: F, F, B, HP (Anywhere) Friendship - The Charleston: RN, RN, RN, U (Anywhere) Animality - Shark: (Hold BL), U, U, D, D (Close) Brutality: HP, HK, HP, HK, -

Mortal Kombat II Tournament

SPECIAL SECTION GAMING INSURRECTION’S TOURNAMENT from the editor aming Insurrection, as a whole, is a longtime fan of the G Mortal Kombat franchise, and in 2010, we brainstormed about ways to put that love into play. The plan material- ized in a competition under tournament conditions. The result was our Mortal Kombat II tournament. Completed through a year and a half of recording, writing and analyzing, myself and former Associate Editor Jamie Mosley played through a double-elimination bracket. The results were highly surprising. Fan favorites (and some of our own personal favorites) made it far. Others did not. Tiers were clearly defined and broken down, a truly fascinating process to watch unfold. Also part of the tournament was an experiment to see if our high level of play matched up with a long-ago ranking chart from the now-defunct GamePro magazine. We’re happy to say that it didn’t necessarily match tier for tier. The results of our tournament revealed just what we hypothesized: Everyone plays Mortal Kombat II differently, and when it comes down to it, tiers aren’t necessarily as important as one would think. This special section is the culmination of hard work and Lyndsey Hicks, editor-in-chief fun. Read on for bone-crunching analysis, tips and ideas we learned as we completed our first Mortal Kombat II tourna- ment. COMPLETE TOURNAMENT BRACKETS WHAT’S INSIDE Rounds 1-6 analysis...............3-13 GamePro chart analysis.............14 Gaming Insurrection’s analysis....15 Tournament statistics...............16 2 special section match analysis: round 1 JAX VS. -

Mortal Kombat II - Special Moves

Mortal Kombat II - Special Moves Liu Kang Special Moves: High Fireball: F, F, HP (can be performed in air too) Low Fireball: F, F, LP Flying Kick: F, F, HK Bicycle Kick: Hold LK for 4 seconds Finishing Moves: Fatality 1: D, F, B, B, HK (close) Fatality 2: Hold BL, D, F, Up, B, D, F... (sweep) Friendship: F, B, B, B, LK Babality: D, D, F, B, LK Stage: Hold BL, B, F, F, LK (close) Kung Lao Special Moves: Teleport: D, Up Diving Kick: D + HK (in air) Hat Throw: B, F, LP (Use Up and D to control the hat) Whirlwind Spin: Up, Up, LK (keep pressing LK to spin longer) Head butt: HP (close) Finishing Moves: Fatality 1: F, F, F, LK (sweep) Fatality 2: Hold LP, B, F, release LP (far) - SG Fatality 2: Hold LP, B, F, release LP (far), control the hat with Up and D so that it hits your opponents neck - A, PC, S32, SS, SN, PSX,PS2, XB, GC, PSP Friendship: B, B, B, D, HK Babality: B, B, F, F, HK Stage: F, F, F, HP (close) Johnny Cage Special Moves: Drop-Kick: HK or LK (close) Shadow Kick: B, F, LK Low Green Bolt: B, D, F, LP High Green Bolt: F, D, B, HP Shadow Uppercut: B, D, B, HP Ball Breaker: LP + BL (close) Finishing Moves: Fatality 1: D, D, F, F, LP (close) Fatality 2: F, F, D, Up (close), Hold D + LP + LK + BL until Cage performs the move and he will knock off three heads Friendship: D, D, D, D, HK Babality: B, B, B, HK Stage: D, D, D, HK (close) Reptile Special Moves: Acid Spit: F, F, HP Slide: B + LP + LK + BL - A, PC, SS, SN, PSX, PS2, XB, GC, PSP Slide: B + LK + HK - SG, S32 Forceball: B, B, HP + LP Invisibility: Up, Up, D, HP (using BL) Finishing -

Haitian Creole – English Dictionary

+ + Haitian Creole – English Dictionary with Basic English – Haitian Creole Appendix Jean Targète and Raphael G. Urciolo + + + + Haitian Creole – English Dictionary with Basic English – Haitian Creole Appendix Jean Targète and Raphael G. Urciolo dp Dunwoody Press Kensington, Maryland, U.S.A. + + + + Haitian Creole – English Dictionary Copyright ©1993 by Jean Targète and Raphael G. Urciolo All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the Authors. All inquiries should be directed to: Dunwoody Press, P.O. Box 400, Kensington, MD, 20895 U.S.A. ISBN: 0-931745-75-6 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 93-71725 Compiled, edited, printed and bound in the United States of America Second Printing + + Introduction A variety of glossaries of Haitian Creole have been published either as appendices to descriptions of Haitian Creole or as booklets. As far as full- fledged Haitian Creole-English dictionaries are concerned, only one has been published and it is now more than ten years old. It is the compilers’ hope that this new dictionary will go a long way toward filling the vacuum existing in modern Creole lexicography. Innovations The following new features have been incorporated in this Haitian Creole- English dictionary. 1. The definite article that usually accompanies a noun is indicated. We urge the user to take note of the definite article singular ( a, la, an or lan ) which is shown for each noun. Lan has one variant: nan. -

Mortal Web Fat.Indd

FATALITIES FOR ASHRAH Fatality 1 - g,g,c,c,2 (close) Fatality 2 - a,g,a,g,2 (sweep) Hara Kiri - c,g,c,c,2 FATALITIES FOR BARAKA Fatality 1 - a,c,g,2 (close) Fatality 2 - a,g,e,a,2 (sweep) Hara Kiri - g,e,c,e,4 FATALITIES FOR BO RAI CHO Fatality 1 - g,c,a,a,2 (sweep) Fatality 2 - c,e,a,3 (sweep) Hara Kiri - e,e,a,a,2 FATALITIES FOR DAIROU Fatality 1 - g,c,e,e,1 (sweep) Fatality 2 - g,g,e,3 (close) Hara Kiri - e,e,e,g,1 FATALITIES FOR DARRIUS FATALITIES Fatality 1 - c,g,e,a,3 (sweep) Fatality 2 - g,a,a,c,1 (close) Hara Kiri - e,a,a,2 FATALITIES FOR ERMAC Fatality 1 - g,e,e,g,3 (sweep) Fatality 2 - e,g,e,g,4 (sweep) Hara Kiri - g,c,c,g,3 FATALITIES FOR HAVIK Fatality 1 - g,a,a,c,4 (close) Fatality 2 - a,a,a,e,2 (sweep) Hara Kiri - a,c,c,c,2 FATALITIES FOR HOTARU Fatality 1 - a,c,e,g,1 (sweep) Fatality 2 - g,a,e,a,2 (close) Hara Kiri - c,e,e,e,2 FATALITIES FOR JADE Fatality 1 - e,a,c,a,1 (sweep) Fatality 2 - e,a,a,a,2 (close) Hara Kiri - a,a,a,e,2 FATALITIES FOR KABAL Fatality 1 - a,c,c,c,3 (close) Fatality 2 - c,c,g,g,2 (close) Hara Kiri - a,c,c,g,2 FATALITIES FOR KENSHI FATALITIES Fatality 1 - a,a,e,e,2 (sweep) Fatality 2 - c,a,e,a,2 (sweep) Hara Kiri - g,e,e,a,4 FATALITIES FOR KIRA Fatality 1 - e,a,a,e,4 (far) Fatality 2 - c,a,g,e,3 (sweep) Hara Kiri - a,e,c,e,3 FATALITIES FOR KOBRA Fatality 1 - g,e,a,g,4 (close) Fatality 2 - a,e,a,a,2 (close) Hara Kiri - c,e,e,2 FATALITIES FOR LI MEI Fatality 1 - a,a,a,a,1 (sweep) Fatality 2 - c,e,a,a,4 (sweep) Hara Kiri - c,g,c,g,3 FATALITIES FOR LIU KANG Fatality 1 - e,e,e,a,2 (sweep) Fatality 2 - a,a,c,c,3 -

Høstfest 2010 Comm 281 State University Moorhead, to Become Members of the Members of the Northern Northern State University, Conference

LOOK IN NEXT WEEK’S ISSUE FOR STORIES ON ... Hispanic Heritage Red & Green Celebration! October 14, 2010 Vol. 92 No. 6 Minot State University, Minot, N.D. 58701 www.minotstateu.edu/redgreen NOTSTOCK Ben Daggett, former MSU student, pours paint for his silkscreen project at MSUʼs fourth- annual NOTSTOCK event last week in the Beaver Dam. Photo by Max Patzner Jones Submitted Photo Members of NSIC to visit campus By Cassandra Simonton Minnesota State, Minnesota Sioux Falls have both applied Høstfest 2010 Comm 281 State University Moorhead, to become members of the Members of the Northern Northern State University, conference. NSIC is consider - Sun Intercollegiate Southwest Minnesota State ing their requests. MSUʼs Piper Jones crowned Miss Høstfest Conference (NSIC) will come University, St. Cloud State “The move is something By Amy Olson Scandinavian heritage festival to Minot State University Oct. University, Upper Iowa we’ve been working on for a Comm 281 and it is held right here, in 19-20 and tour the campus to University, Wayne State while,” Rick Hedberg, MSU Lefse, lutefisk and lap - good ole Minot, N.D. The evaluate it for admittance to College and Wisconsin State athletic director said, “To skaus, oh my! If you were in event features a variety of the conference. University. raise the bar across campus. the Minot area lately you've entertainment, Scandinavian The NSIC is comprised of With 14 colleges in the con - We’ve done a study of aspira - probably heard Ole and Lena cuisine (like lapskaus - a coun - Augustana College, Bemidji ference, NSIC is looking to tional peers in situations and jokes, seen roads full of RVs, try soup) and cultural presen - State University, Concordia upgrade to 16 and possibly many of the schools we aspire and been asked, “Where are tations for all ages to enjoy. -

Mortal Kombat Mythologies Pdf, Epub, Ebook

MORTAL KOMBAT MYTHOLOGIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK W. Roberts | 91 pages | 01 Oct 1997 | Prima Publishing,U.S. | 9780761512158 | English | Rocklin, United States Mortal Kombat Mythologies PDF Book Players will find plenty of back story to outline the appearance of other popular Mortal Kombat characters such as Raiden and Liu Kang. More GameSpot Reviews. Jeff Gerstmann Jeff Gerstmann has been professionally covering the video game industry since The most unfortunate stench to ever pollute the N64 office. The quest remains true to the Mortal Kombat world, with many of the attacks we all know and love. The teeth of disk holder are undamaged. Click anywhere outside of the emulator screen to show controls. Even Super Hunchback was better. Email to friends Share on Facebook - opens in a new window or tab Share on Twitter - opens in a new window or tab Share on Pinterest - opens in a new window or tab. From the moment the gruff voice first announced 'Finish him', a nation of gameplayers was hooked, computer-generated violence changed forever and now no self-respecting beat-'em-up can be seen out in public without at least one horrific fatality per character and enough blood to keep the Red Cross going for months. The unusual part, though, is the moves themselves, for they must be learnt. G-Police: Weapons of Justice. Besides fighting-type moves, Sub-Zero will also be able to hang from ledges and pull himself up see upper-right picture. Trip the next pillar, then run past it. Omega Assault. Game Information. Back to home page. -

The Elder of the Two Brothers Who Takes the Name Sub-Zero, Called Bì

The elder of the two brothers who takes the name Sub-Zero, called Bì Hán (Chinese: 避寒; pinyin: Bìhán), [3] was introduced in the first Mortal Kombat game where he participates in the titular tournament as he was ordered by the Lin Kuei to kill the host Shang Tsung and take his treasure.[4] He fails to accomplish his mission, and is killed by the specter Scorpion, who sought to avenge his own death.[5] Bi-Han then becomes the undead Noob Saibot.[6][7] In the direct sequel Mortal Kombat II, Bi-Han's place is taken by his brother Kuai Liang (Chinese: 快 涼; pinyin: Kuàiliáng), whose codename originally known as Tundra prior assuming his older brother's codename to honor him. Upon his brother's death in the first tournament and the survival of Shang Tsung, Kuai Liang[3] is sent by the Lin Kuei to complete his brother's unfinished task.[5] In Mortal Kombat 3, the younger Sub- Zero escapes from the Lin Kuei who wanted to transform their warriors into cyborgs.[8] They program three cyborg assassins to hunt and terminate Sub-Zero (one of which being his old friend, Smoke, who failed to escape), who by this time had received a vision from Raiden and agreed to join the rebellion against a new threat.[9] In addition to the current Sub-Zero, Ultimate Mortal Kombat 3 and Mortal Kombat Trilogy included a playable character known as "Classic Sub-Zero".[10] His biography states that although he was believed to have died after the first Mortal Kombat, he returned to try again and assassinate Shang Tsung.[11] However, his ending states that he is not Sub-Zero,