Treacherous Correspondence on the Renaissance Stage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treasonous Silence: the Tragedy of Philotas And

kevin curran Treasonous Silence: The Tragedy of Philotas and Legal Epistemology [with illustrations]enlr_1099 58..89 n 1605 something curious happened in the world of elite theater. ISamuel Daniel, a writer of rare and wide-ranging talent, with years of experience navigating high-profile patronage networks, made a major blunder. He allowed an edgy political play originally composed as a closet drama to get dragged onto the stage at court.The play, The Tragedy of Philotas, told the story of the title-character, a successful but problematically ambitious military commander who fails to report a treasonous plot against the life of Alexander the Great and whose reticence causes him to become implicated in that plot. Philotas’ trial in Act 4 of the play leads ultimately to his conviction and death, as well as his condemnation by a moralizing chorus in Act 5. But the trial scene itself sets Philotas up as the victim of political paranoia and the opportunistic persecution of Alexander’s conniving adviser, Craterus. After the performance, Daniel was promptly summoned to appear before King James’s Privy Council where he was accused of using Philotas to dramatize sympathetically certain aspects of the career and downfall of Robert Devereux, second Earl of Essex, who had been executed for high treason four years earlier after a failed insurrection against Queen Elizabeth. No records of this appearance survive, but two letters by Daniel—one to the Secretary of State, Robert Cecil, the other to his patron, Charles Blount, Lord Mountjoy—as well as an “Apology” which appears to have been written directly following the This essay benefited from generous audiences at the University of Tulsa, Farleigh Dickinson University, the University of North Texas,the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, and meetings of the Renaissance Society of America and the Shakespeare Association of America. -

The Holy See, Social Justice, and International Trade Law: Assessing the Social Mission of the Catholic Church in the Gatt-Wto System

THE HOLY SEE, SOCIAL JUSTICE, AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE LAW: ASSESSING THE SOCIAL MISSION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE GATT-WTO SYSTEM By Copyright 2014 Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma Submitted to the graduate degree program in Law and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D) ________________________________ Professor Raj Bhala (Chairperson) _______________________________ Professor Virginia Harper Ho (Member) ________________________________ Professor Uma Outka (Member) ________________________________ Richard Coll (Member) Date Defended: May 15, 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE HOLY SEE, SOCIAL JUSTICE, AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE LAW: ASSESSING THE SOCIAL MISSION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE GATT- WTO SYSTEM by Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma ________________________________ Professor Raj Bhala (Chairperson) Date approved: May 15, 2014 ii ABSTRACT Man, as a person, is superior to the state, and consequently the good of the person transcends the good of the state. The philosopher Jacques Maritain developed his political philosophy thoroughly informed by his deep Catholic faith. His philosophy places the human person at the center of every action. In developing his political thought, he enumerates two principal tasks of the state as (1) to establish and preserve order, and as such, guarantee justice, and (2) to promote the common good. The state has such duties to the people because it receives its authority from the people. The people possess natural, God-given right of self-government, the exercise of which they voluntarily invest in the state. -

A Brief Chronology of the House of Commons House of Commons Information Office Factsheet G3

Factsheet G3 House of Commons Information Office General Series A Brief Chronology of the August 2010 House of Commons Contents Origins of Parliament at Westminster: Before 1400 2 15th and 16th centuries 3 Treason, revolution and the Bill of Rights: This factsheet has been archived so the content The 17th Century 4 The Act of Settlement to the Great Reform and web links may be out of date. Please visit Bill: 1700-1832 7 our About Parliament pages for current Developments to 1945 9 information. The post-war years: 11 The House of Commons in the 21st Century 13 Contact information 16 Feedback form 17 The following is a selective list of some of the important dates in the history of the development of the House of Commons. Entries marked with a “B” refer to the building only. This Factsheet is also available on the Internet from: http://www.parliament.uk/factsheets August 2010 FS No.G3 Ed 3.3 ISSN 0144-4689 © Parliamentary Copyright (House of Commons) 2010 May be reproduced for purposes of private study or research without permission. Reproduction for sale or other commercial purposes not permitted. 2 A Brief Chronology of the House of Commons House of Commons Information Office Factsheet G3 Origins of Parliament at Westminster: Before 1400 1097-99 B Westminster Hall built (William Rufus). 1215 Magna Carta sealed by King John at Runnymede. 1254 Sheriffs of counties instructed to send Knights of the Shire to advise the King on finance. 1265 Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, summoned a Parliament in the King’s name to meet at Westminster (20 January to 20 March); it is composed of Bishops, Abbots, Peers, Knights of the Shire and Town Burgesses. -

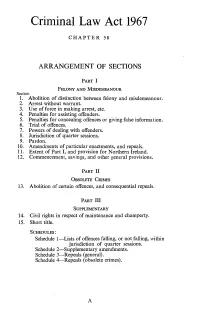

Arrangement of Sections

Criminal Law Act 1967 CHAPTER 58 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Section 1. Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. 2. Arrest without warrant. 3. Use of force in making arrest, etc. 4. Penalties for assisting offenders. 5. Penalties for concealing offences or giving false information. 6. Trial of offences. 7. Powers of dealing with offenders. 8. Jurisdiction of quarter sessions. 9. Pardon. 10. Amendments of particular enactments, and repeals. 11. Extent of Part I, and provision for Northern Ireland. 12. Commencement, savings, and other general provisions. PART 11 OBSOLETE CRIMES 13. Abolition of certain offences, and consequential repeals. PART III SUPPLEMENTARY 14. Civil rights in respect of maintenance and champerty. 15. Short title. SCHEDULES: Schedule 1-Lists of offences falling, or not falling, within jurisdiction of quarter sessions. Schedule 2-Supplementary amendments. Schedule 3-Repeals (general). Schedule 4--Repeals (obsolete crimes). A Criminal Law Act 1967 CH. 58 1 ELIZABETH n , 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] E IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and BTemporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR 1.-(1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are J\b<?liti?n of hereby abolished. -

268KB***The Law on Treasonable Offences in Singapore

Published on e-First 14 April 2021 THE LAW ON TREASONABLE OFFENCES IN SINGAPORE This article aims to provide an extensive and detailed analysis of the law on treasonable offences in Singapore. It traces the historical development of the treason law in Singapore from the colonial period under British rule up until the present day, before proceeding to lay down the applicable legal principles that ought to govern these treasonable offences, drawing on authorities in the UK, India as well as other Commonwealth jurisdictions. With a more long-term view towards the reform and consolidation of the treason law in mind, this article also proposes several tentative suggestions for reform, complete with a draft bill devised by the author setting out these proposed changes. Benjamin LOW1 LLB (Hons) (National University of Singapore). “Treason doth never prosper: what’s the reason? Why, if it prosper, none dare call it treason.”2 I. Introduction 1 The law on treasonable offences, more commonly referred to as treason,3 in Singapore remains shrouded in a great deal of uncertainty and ambiguity despite having existed as part of the legal fabric of Singapore since its early days as a British colony. A student who picks up any major textbook on Singapore criminal law will find copious references to various other kinds of substantive offences, general principles of criminal liability as well as discussion of law reform even, but very little mention is made of the relevant law on treason.4 Academic commentary on this 1 The author is grateful to Julia Emma D’Cruz, the staff of the C J Koh Law Library, the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and the ISEAS Library for their able assistance in the author’s research for this article. -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1967. (See end of Document for details) Criminal Law Act 1967 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Annotations: Extent Information E1 Subject to s. 11(2)-(4) this Part shall not extend to Scotland or Northern Ireland see s. 11(1) 1 Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. (1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are hereby abolished. (2) Subject to the provisions of this Act, on all matters on which a distinction has previously been made between felony and misdemeanour, including mode of trial, the law and practice in relation to all offences cognisable under the law of England and Wales (including piracy) shall be the law and practice applicable at the commencement of this Act in relation to misdemeanour. [F12 Arrest without warrant. (1) The powers of summary arrest conferred by the following subsections shall apply to offences for which the sentence is fixed by law or for which a person (not previously convicted) may under or by virtue of any enactment be sentenced to imprisonment for a term of five years [F2(or might be so sentenced but for the restrictions imposed by 2 Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. -

Parliament and the Tudor Succession Crisis

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1999 Parliament and the Tudor Succession Crisis Lauri Bauer Coleman College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Coleman, Lauri Bauer, "Parliament and the Tudor Succession Crisis" (1999). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626228. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-g3g0-en82 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PARLIAMENT AND THE TUDOR SUCCESSION CRISIS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts by Lauri Bauer Coleman 1999 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts CZ&Lua L Lauri Bauer Coleman Approved, August 1999 Lu Ann Homza Ronald Hoffman TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ................................... iv Abstract...............................................................................................................................v Introduction....................................................................................................................... -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Criminal Law Act 1967 CHAPTER 58 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Section 1. Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. 2. Arrest without warrant. 3. Use of force in making arrest, etc. 4. Penalties for assisting offenders. 5. Penalties for concealing offences or giving false information. 6. Trial of offences. 7. Powers of dealing with offenders. 8. Jurisdiction of quarter sessions. 9. Pardon. 10. Amendments of particular enactments, and repeals. 11. Extent of Part I, and provision for Northern Ireland. 12. Commencement, savings, and other general provisions. PART II OBSOLETE CRIMES 13. Abolition of certain offences, and consequential repeals. PART III SUPPLEMENTARY 14. Civil rights in respect of maintenance and champerty. 15. Short title. SCHEDULES : Schedule 1-Lists of offences falling, or not falling, within jurisdiction of quarter sessions. Schedule 2-Supplementary amendments. Schedule 3-Repeals (general). Schedule 4--Repeals (obsolete crimes). A Criminal Law Act 1967 CH. 58 1 ELIZABETH II 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] BE IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR 1.-(1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are Abolition of abolished. -

Form and Accessibility of the Law Applicable in Wales

Law Commission Consultation Paper No 223 FORM AND ACCESSIBILITY OF THE LAW APPLICABLE IN WALES A Consultation Paper ii THE LAW COMMISSION – HOW WE CONSULT About the Commission: The Law Commission is the statutory independent body created by the Law Commissions Act 1965 to keep the law under review and to recommend reform where it is needed. The Law Commissioners are: The Rt Hon Lord Justice Lloyd Jones (Chairman), Stephen Lewis, Professor David Ormerod QC and Nicholas Paines QC. The Chief Executive is Elaine Lorimer. Topic of this consultation paper: The form and accessibility of the law applicable in Wales. Availability of materials: This consultation paper is available on our website in English and in Welsh at http://www.lawcom.gov.uk. Duration of the consultation: 9 July 2015 to 9 October 2015. How to respond Please send your responses either: By email to: [email protected] or By post to: Sarah Young, Law Commission, 1st Floor, Tower, Post Point 1.54, 52 Queen Anne’s Gate, London SW1H 9AG Tel: 020 3334 3953 If you send your comments by post, it would be helpful if, where possible, you also send them to us electronically. After the consultation: In the light of the responses we receive, we will decide our final recommendations and we will present them to the Welsh Government. Consultation Principles: The Law Commission follows the Consultation Principles set out by the Cabinet Office, which provide guidance on type and scale of consultation, duration, timing, accessibility and transparency. The Principles are available on the Cabinet Office website at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/consultation-principles-guidance. -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Status: Point in time view as at 01/02/1991. This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1967. (See end of Document for details) Criminal Law Act 1967 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Extent Information E1 Subject to s. 11(2)-(4) this Part shall not extend to Scotland or Northern Ireland see s. 11(1) 1 Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. (1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are hereby abolished. (2) Subject to the provisions of this Act, on all matters on which a distinction has previously been made between felony and misdemeanour, including mode of trial, the law and practice in relation to all offences cognisable under the law of England and Wales (including piracy) shall be the law and practice applicable at the commencement of this Act in relation to misdemeanour. [F12 Arrest without warrant. (1) The powers of summary arrest conferred by the following subsections shall apply to offences for which the sentence is fixed by law or for which a person (not previously convicted) may under or by virtue of any enactment be sentenced to imprisonment for a term of five years [F2(or might be so sentenced but for the restrictions imposed by [F3section 33 of the Magistrates’Courts Act 1980)]] and to attempts to committ any 2 Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. -

Chapter 9: an Overview of British Constitutional History: the King And

Chapter 9: An Overview of British Constitutional History: the King appoint ministers, and to veto legislation, but informally the Crown has deferred to Commons on these matters for more than a century. and the Medieval Parliament Neither the mutli-document character of the English constitution, nor the complexity of its unwritten informal constitution is unusual among the countries Two chapters are devoted to developing an overview of the constitutional history analyzed in the present study. What is unusual about the English constitution is its of the United Kingdom. This is done for three reasons: first, most English language longevity and the fact that none of its written documents describe formal procedures of readers will be most familiar with this history, although they will not generally be constitutional amendment that are more stringent than for changes in ordinary familiar with its constitutional developments. Most historians focus on the great legislation. The relative ease of amendment has allowed more constitutional legislation tapistry of history rather than a single very important strand of developments, and thus to be passed and, thus, a more gradual path of constitutional development than in the telling the tale provides a useful illustration of how the analytical models can be used as other modern kingdoms of northern Europe, but its constitutional core has remained a lense though which to view hitory. Second, the English history demonstrates very extraordinarily stable. The medieval constitution remained substantially in place for 400 clearly the robustness of the King and Council template. Although times were often hundred years, except for two decades in the seventeenth century. -

Viewed As a Threat to Himself and to the Crown

! MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Sarah Elizabeth Donelson Candidate for the Degree: Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________ Director Dr. Judith P. Zinsser ______________________________________ Reader Dr. Renee Baernstein _______________________________________ Reader Dr. Charlotte Goldy ______________________________________ Reader Dr. Stephen Norris _______________________________________ Graduate School Representative Dr. Katharine Gillespie ! ! ABSTRACT BY NO ORDINARY PROCESS: TREASON, GENDER, AND POLITICS UNDER HENRY VIII by Sarah Elizabeth Donelson Using the treason statute of 1534 and the Pole/Courtenay treason case of 1538, I explore how the intersection of treason, gender, and personal politics subverted and then changed the gender paradigm for traitors in the sixteenth century. The Poles and Courtenays were descended from the Plantagenets, the ruling dynasty in England before the Tudors, and as such were a threat to Henry VIII and the stability of his throne. After one member of the Pole family, Cardinal Reginald Pole, was declared a traitor by the king, Henry VIII and his principal minister, Thomas Cromwell, embarked upon an investigation of his family and friends. What they found convinced them that these two families were guilty of high treason and planning to replace him on the throne. The Pole/ Courtenay case shows the instability of customary gender assumptions both in English politics and the legislation and prosecution of treason. Though the process of the investigation, prosecution, and sentencing, the state changed what it meant to be a traitor in terms of gender. ! ! BY NO ORDINARY PROCESS: TREASON, GENDER, AND POLITICS UNDER HENRY VIII A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History by Sarah Elizabeth Donelson Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2012 Dissertation Director: Dr.