Does Hip Contracture Effect Anterior Pelvic Tilt Changes During Squatting?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SIMMONDS TEST: Patient Is Prone Doctor Flexes the Patients Knee to 90 Degrees Doctor Squeezes the Patient’S Calf

Clinical Orthopedic Testing Review SIMMONDS TEST: Patient is prone Doctor flexes the patients knee to 90 degrees Doctor squeezes the patient’s calf. Classical response: Failure of ankle plantarflexion Classical Importance= torn Achilles tendon Test is done bilaterally ACHILLES TAP: Patient is prone Doctor flexes the patient’s knee to 90 degree Doctor dorsiflexes the ankle and then strikes the Achilles tendon with a percussion hammer Classical response: Plantar response Classical Importance= Intact Achilles tendon Test is done bilaterally FOOT DRAWER TEST: Patient is supine with their ankles off the edge of the examination table Doctor grasps the heel of the ankle being tested with one hand and the tibia just above the ankle with the other. Doctor applies and anterior to posterior and then a posterior to anterior sheer force. Classical response: Anterior or posterior translation of the ankle Classical Importance= Anterior talofibular or posterior talofibular ligament laxity. Test is done bilaterally LATERAL STABILITY TEST: Patient is supine Doctor grasps the tibia with one hand and the foot with the other. Doctor rotates the foot into inversion Classical response: Excessive inversion Classical Importance= Anterior talofibular ligament sprain Test is done bilaterally MEDIAL STABILITY TEST: Patient is supine Doctor grasps the tibia with one hand and the foot with the other Doctor rotates the foot into eversion Classical response: Excessive eversion Classical Importance= Deltoid ligament sprain Test is done bilaterally 1 Clinical Orthopedic Testing Review KLEIGER’S TEST: Patient is seated with the legs and feet dangling off the edge of the examination table. Doctor grasps the patient’s foot while stabilizing the tibia with the other hand Doctor pulls the ankle laterally. -

Sacroiliac Joint N Ischium N Ilium N Pubis James R

Pelvic Anatomy Evidence-Based Evaluation & Treatment n Innominates of the Sacroiliac Joint n ischium n ilium n pubis James R. Scifers, DScPT, LAT, ATC Moravian College n Sacrum Athletic Training Program Articulations Biomechanics of the Pelvis n Function of the SI Joint n transmit vertical forces n Sacroiliac Joints n transmit ground n Pubic Symphysis reaction forces n Lumbo-Sacral Joint Sacral Motions Arthrokinematics of the SI Joint n During trunk flexion… n Sacral Base (S1) n Initially, sacral flexion occurs (base of sacrum n Sacral Apex (S5) moves anterior) n Flexion (nutation) n Later, sacral extension occurs with continued trunk flexion (base of sacrum moves posterior) n occurs during exhalation n Extension (counternutation) n occurs during inhalation 1 Dysfunction Classification Ilio-Sacral (IS) Dysfunctions n Sacroiliac Joint (SIJ) n Named for motion at n Any injury to SIJ PSIS n Ilio-Sacral (IS) n anterior rotation n ilium (innominate) n posterior rotation moving on sacrum n up-slip n Sacro-Iliac (SI) n down-slip (rare) n sacrum moving on ilium n in-flare n Pubic Shear n out-flare n Pubic symphysis / Pubic shear lesion Sacro-Iliac (SI) Dysfunctions Pubic Shear Lesions n Sacral Rotations n Named for “direction facing on axis” n Named for any movement at pubic n Forward Rotations symphysis n right on right n Indicates injury to pubic n left on left symphysis n Backward Rotations n right on left n left on right SI Evaluation Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) n Reliability (k) is reproducibility of test results, can be n History* intra-tester (within one clinician) or inter-tester (between n Observation** multiple clinicians) n Palpation** n Sensitivity (sens) is the ability of test to RULE OUT a condition. -

Common Causes of Hip Pain

Common Causes of Hip Pain • Osteoarthritis • Osteonecrosis Physical Examination of the Hip • Sciatica • Stress Fracture • Infection • Impingement / labral tear • Trochanteric Bursitis • IT Band Pathology Physical Exam 1. Gait analysis 2. Examination Standing • Hip / spinal alignment • Crouch may be hip contracture Gait Analysis 3. Examination Supine • Palpation • Range-of-motion • Strength testing • Distal pulses 4. Provocative maneuvers Pathologic Gait Antalgic: Shortened stance on painful side Steppage: Leg lifts higher to clear ground Waddling: Broad-based, pelvis drops towards raised leg during swing . proximal myopathy Trandelenburg: Trunk towards weak side during stance . abductor weakness Look at posture…leaning forward might be spine Steppage gait . Antalgic gait . - Compensatory for foot drop - “Limping” - Exaggerated hip flexion - Shortened stance allows foot on weak side to clear ground phase on painful / - Tibialis anterior weakness affected limb -RX: • AFO brace, • Refer, especially if acute Trandelenburg gait . - Weak abductors - Superior gluteal nerve - Prior hip surgery Exam Standing . - Walk around the patient - Overall posture - Pelvic tilt Exam Standing • Scoliosis • Leg length discrepancy - Crouch • Hip contracture • Spinal hyperlordosis - Adductor contracture Exam Supine . - Palpation… • know your anatomy / landmarks - Range of motion . Exam Supine • Flexion: 110 - 120° • Extension: 10 - 15° • IR/ER: 30 - 40° / 40 – 60° - Strength and sensation testing - Don’t forget distal pulses Exam Supine . Exam Supine . - Inspection -

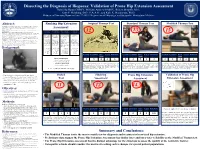

Prone Hip Extension Assessment Gabriella Baran OMSIV, William Andrew OMSIV, Robert Murphy, M.S., Kurt P

Dissecting the Diagnosis of Iliopsoas: Validation of Prone Hip Extension Assessment Gabriella Baran OMSIV, William Andrew OMSIV, Robert Murphy, M.S., Kurt P. Heinking, D.O., F.A.A.O., and Kyle K. Henderson, Ph.D. Midwestern University, Downers Grove, IL60515; Departments of Physiology, and Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine Abstract: Ranking Hip Extension Original Thomas Test Standard Thomas Test Modified Thomas Test Introduction: The father of British Orthopaedic surgery, Hugh Owen Thomas, is recognized for his method to assess hip flexion contracture in patients with Potts disease. The “Thomas Test” was modified to assess the iliopsoas muscle in healthy patients. In Osteopathic medical schools, prone hip extension is also used to Assessment: appreciate a palpable barrier. Objective: Provide historical context for hip extension assessment for medical education and validate prone hip extension assessment. 13 Versatility Specialization Muscle Groups Accuracy Methods: IRB approval was obtained (MWU#2852) and subjects assessed with the Modified- 12 15 Thomas Test (MTT), prone hip extension, and other structural examinations: pelvic side shift, leg length, lumbar curve, seated and standing flexion tests. A digital goniometer and force plate transducer were used to assess Applicability to Applicability to a # of muscle groups Diagnosis prone hip range of motion (ROM) and physician applied force. Results: The MTT, utilizing gravity as the force for hip extension, had high intra-rater reliability (0.969). different patient specific patient assessed and/or ability consistency: Preliminary data for prone hip extension assessment had high intra-rater reliability for ROM (0.973) and the populations: population: to treat: force required to reach the perceived restrictive barrier (0.928). -

Medical Tests, Signs & Maneuvers Guide

Medical Tests, Signs & Maneuvers Guide Achilles Squeeze test: For Achilles This can be performed with tendon rupture. Squeezing the calf Doppler placed on the digits muscle fails to produce plantar during test. The test is valuable flexion of the ankle joint. Also called prior to an invasive procedure on Simmons Test, Thompson test. the arteries at the wrist, Addis test: For determination of Allis' sign: Relaxation of the leg length discrepancy. With fascia between the crest of the patient in prone position, flexing ilium and the greater trochanter: a the knees to 90 degrees reveals the sign of fracture of the neck of the potential discrepancies of both femur. tibial and femoral lengths. Amoss' sign: In painful flexure of Adson's maneuver: See under the spine, the patient, when rising Adson's test to a sitting posture from lying in bed, does so by supporting him- For thoracic outlet Adson's test: self with his hands placed far syndrome. With the patient in a behind him in the bed. sitting position, his hands resting on thighs, the examiner palpates Anghelescu's sign: Inability to both radial pulses as the patient bend the spine while lying on the rapidly fills his lungs by deep back so as to rest on the head and inspiration and, holding his breath, heels alone, seen in tuberculosis hyperextends his neck and turns of the vertebrae. his head toward the affected side. If the radial pulse on that side is Anterior drawer sign: See under decidedly or completely obliter- drawer sign. ated, the result is considered Anterior tibial sign: Involuntary positive. -

Diagnostic Approach to Hip Pain

Diagnostic Approach to Hip Pain Zoë J. Foster, MD October 3, 2018 Disclosures I have nothing to disclose. Objectives • Review examination of the hip, including special tests • Discuss differential diagnosis for hip pain • Consider special diagnoses not to be missed Anatomy Images from: Sonosim Case 1: Anterior hip pain 15yo track athlete with worsening R groin pain tripped and fell in her yard a year ago, now with pain x 6 months dull constant achy pain, 4-5/10 radiation to anterior thigh hard to get comfortable at night hard to go up and down stairs one at a time can’t run due to pain better with ibuprofen no history of hip problems prior Differential Diagnosis for Hip Pain INTRA-ARTICULAR CAUSES EXTRA-ARTICULAR CAUSES Labral tear Adhesive capsulitis Loose bodies (including OCD lesions) Snapping hip (internal or external) Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) Greater trochanteric pain syndrome Synovitis Piriformis syndrome Tears of ligamentum teres Ostetis pubis Chondral injury Sports hernia Avascular necrosis Myotendinous injuries Avulsion injuries (ASIS, etc) Stress fractures Nerve compression syndromes From: Poultsides, L. A., Bedi, A., & Kelly, B. T. (2012). An Algorithmic Approach to Mechanical Hip Pain. HSS Journal, 8(3), 213–224. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11420-012-9304-x Locations of “Hip Pain” From: Wilson JJ, Furukawa M. Evaluation of the patient with hip pain. American Family Physician. 2014; 89(1): 27-34 Differential Diagnosis for Hip Pain ANTERIOR LATERAL POSTERIOR Osteoarthritis Greater trochanteric pain syndrome Piriformis syndrome -

Orthopaedic Examination Spinal Cord / Nerves

9/6/18 OBJECTIVES: • Identify the gross anatomy of the upper extremities, spine, and lower extremities. • Perform a thorough and accurate orthopaedic ORTHOPAEDIC EXAMINATION examination of the upper extremities, spine, and lower extremities. • Review the presentation of common spine and Angela Pearce, MS, APRN, FNP-C, ONP-C extremity diagnoses. Robert Metzger, DNP, APRN, FNP - BC • Determine appropriate diagnostic tests for common upper extremity, spine, and lower extremity problems REMEMBER THE BASIC PRINCIPLES OF MUSCULOSKELETAL EXAMINATION Comprehensive History Comprehensive Physical Exam THE PRESENTERS • Chief Complaint • Inspection • HPI OLDCART • Palpation HAVE NO CONFLICTS OF INTEREST • PMH • Range of Motion TO REPORT • PSH • Basic principles use a goniometer to assess joint ROM until you can • PFSH safely eyeball it • ROS • Muscle grading • Physical exam one finger point • Sensation to maximum pain • Unusual findings winging and atrophy SPINAL COLUMN SPINAL CORD / NERVES • Spinal cord • Begins at Foramen Magnum and • Consists of the Cervical, Thoracic, continues w/ terminus at Conus Medullaris near L1 and Lumbar regions. • Cauda Equina • Collection of nerves which run from • Specific curves to the spinal column terminus to end of Filum Terminale • Lordosis: Cervical and Lumbar • Nerve Roots • Kyphosis: Thoracic and Sacral • Canal is broader in cervical/ lumbar regions due to large number of nerve roots • Vertebrae are the same throughout, • Branch off the spinal cord higher except for C1 & C2, therefore same than actual exit through -

Administration Guidelines for the Spinal Alignment and Range Of

The Spinal Alignment and Range of Motion Measure (SAROMM) © 2005 Doreen Bartlett I would like to acknowledge the following people for participating in the development of this instrument: Wendy Chan BScPT candidate at the time, for her participation in the initial item generation (1999). Diane Dupuis BScPT candidates, for the initial protocol development and pilot Rhonda Foster testing of the Joint Alignment and Functional Range of Motion Sunita Karmakar Measure (1999-2000). Victoria Szwajcer Susann Cox Physical therapists at the Five Counties Children’s Centre in Gill Davis Peterborough, Ontario, for participating in refinement of the items Kelly Holy through a focus group and three iterations using the Jennifer Mai Delphi process. Special thanks to Barbara Purdie, who Barbara Purdie coordinated sessions with clients of the Centre to have Sharon White photographs taken to support the training manual (2001). All of these therapists, and Susan Pecoskie and Angela Harrison, participated in the feasibility testing and preliminary and final reliability testing of the SAROMM (2002 and 2003). Robert Palisano Professor, Program in Rehabilitation Sciences, Drexel University in Philadelphia, and a colleague through CanChild, Centre for Childhood Disability Research at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, has provided valuable input through the process of instrument refinement. Andrea Clarke Physical therapists at the Children’s Rehabilitation Centre Bonnie Darbyson of Essex County in Windsor, Ontario, for reviewing a “final” Anne Girard version of the Spinal Alignment and Range of Motion Measure Laurie Lessard (2001). Jayne Garland For participating in additional photographs of items recommended in the feasibility study. Patricia Darling For technical assistance preparing this training manual. -

Differentiating Hip Pathology from Lumbar Spine Pathology: Key Points of Evaluation and Management

Instructional Course Lecture Differentiating Hip Pathology From Lumbar Spine Pathology: Key Points of Evaluation and Management Abstract Aaron J. Buckland, MBBS, The diagnosis and treatment of patients who have both hip and lumbar FRACS spine pathologies may be a challenge because overlapping Ryan Miyamoto, MD symptoms may delay a correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Rakesh D. Patel, MD Common complaints of patients who have both hip and lumbar spine pathologies include low back pain with associated buttock, groin, James Slover, MS, MD thigh, and, possibly, knee pain. A thorough patient history should be Afshin E. Razi, MD obtained and a complete physical examination should be performed in these patients to identify the primary source of pain. Plain and advanced imaging studies and diagnostic injections can be used to further delineate the primary pathology and guide the appropriate sequence of treatment. Both the surgeon and the patient should understand that, although one pathology is managed, the management of the other pathology may be necessary because of persistent pain. The recognition of both entities may help reduce the likelihood of misdiagnosis, and the management of both entities in the appropriate sequence may help reduce the likelihood of persistent symptoms. ip and lumbar spine patholo- symptoms is clear despite coexistent Hgies often occur in combina- hip and lumbar spine pathologies. In tion, which may result in substantial patients with complex hip-spine syn- disability.1-3 Patients with both hip drome, however, no clear source of and lumbar spine pathology com- symptoms is known despite a detailed monly have low back pain (LBP) physical examination. -

Introduction to OMT of Hip and Pelvis

STFM National Convention 2011 New Orleans The Essential Lower Back Exam Judith A. Furlong, M.D., Cathee McGonigle, D.O. & Rob Rutherford, MD Objectives Brief review of the anatomy of the back, (hip and pelvis in Handout) Provide a systematic approach to examine the lower back, hip, and pelvis Overview 60-70% of the adult population has been affected by low back pain at some time in their lives Up to 15-30% may be affected at one time Back pain is a common cause of absenteeism from work in employees between the ages of 30 and 60 years In 1988, an estimated 149 million work days were missed by about 22.4 million people (17.6% of all U.S. workers) due to low back pain Most people have complete resolution of their symptoms in 30 days; others have recurrence or symptoms become chronic Persistance of symptoms should trigger a more extensive work-up for a cause Keep in mind that litigation and Worker’s Compensation claims may significantly affect a person’s pain behavior and impact their motivation to return to work rapidly Brief Review of Anatomy Lumbar Spine Muscles Differential Diagnosis Inflammation Infection Degenerative disorders Neoplasms (primary and metastatic) Trauma Metabolic disorders Developmental defects Neurologic disorders Referred pain Psychological problems Cauda equina syndrome Types of Pain Night pain Acute post-traumatic pain Pain in children Obtaining the History Location, duration, degree, and disability Determine the mechanism of injury or overuse Assess pain severity Establish the location of -

Sacroiliac Orthopedic Tests

SACROILIAC ORTHOPEDIC TESTS Sacroiliac Orthopedic Tests Page 0 of 27 Contents Sacroiliac Orthopedic Tests .................................................................................................................... 4 Reliability and Validity of Sacroiliac Joint Tests .................................................................................. 4 Performance and Interpretation of Sacroiliac Joint Tests ................................................................... 5 Test Combinations ........................................................................................................................... 6 Active Straight Leg Raise (aSLR) (aka pelvic instability test) ......................................................... 8 Mechanism ....................................................................................................................................... 8 Procedural Errors ............................................................................................................................. 8 Interpretation .................................................................................................................................... 8 Charting ............................................................................................................................................ 9 Reliability and Validity ...................................................................................................................... 9 Gaenslen’s Test (aka Pelvic rotation test) ........................................................................................... -

Physical Examination of Lower Extremity

Physical Examination of Lower Extremity Objective 1. Principles of Physical Examination 2. Physical Examination Approach: - Hip & Thigh - Knee - Foot & Ankle Principles of Physical Examination 1. Do not forget the patient - General examination, Vital signs 2. Two sides: right and left 3. Two joints: above and below 4. Two surfaces: front and back Approach to Examination (Any Lower Extremity Joint) 1. General & Gait - General: Well or ill-looking - Vital signs: febrile, hemodynamic stability - Gait cycle - Abnormal gait: antalgic gait, Trendelenburg gait, steppage (foot drop) gait 2. Look (Inspection), Feel (Palpation) & Move (Motion) 3. Special Tests 4. Neurovascular Examination Hip & Thigh 1. Inspection for: - Leg length discrepancy - Alignment & Asymmetry (wasting) - Swelling, Skin changes (erythema), Scars 2. Palpation sites: - From the front: ASIS, pubic tubercle - From the side: greater trochanter - From the back: SI joint, PSIS 3. Motion: Hip Flexion: - Preferred Position: Supine with hips and knees in neutral rotation - Stabilization: Pelvis is stabilized by manual fixation - Goniometer Axis: Femoral Greater Trochanter - Reference (Stationary) Arm: Parallel to midaxillary line of the trunk - Movement (Movable) Arm: Parallel to longitudinal axis of the femur in line with lateral femoral condyle 2 Hip Extension: - Preferred Position: Prone with hips & knees in neutral and feet extending off end of the table - Stabilization: Pelvis is stabilized by manual fixation - Goniometer Axis: Femoral Greater Trochanter - Reference (Stationary)