Thelonious Monk: Life and Influences Thelonious Monk: Life and Influences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duke Ellington Kyle Etges Signature Recordings Cottontail

Duke Ellington Kyle Etges Signature Recordings Cottontail. Cottontail stands as a fine example of Ellington’s “Blanton-Webster” years, where the band was at its peak in performance and popularity. The “Blanton-Webster” moniker refers to bassist Jimmy Blanton and tenor saxophonist Ben Webster, who recorded Cottontail on May 4th, 1940 alongside Johnny Hodges, Barney Bigard, Chauncey Haughton, and Harry Carney on saxophone; Cootie Williams, Wallace Jones, and Ray Nance on trumpet; Rex Stewart on cornet; Juan Tizol, Joe Nanton, and Lawrence Brown on trombone; Fred Guy on guitar, Duke on piano, and Sonny Greer on drums. John Hasse, author of The Life and Genius of Duke Ellington, states that Cottontail “opened a window on the future, predicting elements to come in jazz.” Indeed, Jimmy Blanton’s driving quarter-note feel throughout the piece predicts a collective gravitation away from the traditional two feel amongst modern bassists. Webster’s solo on this record is so iconic that audiences would insist on note-for-note renditions of it in live performances. Even now, it stands as a testament to Webster’s mastery of expression, predicting techniques and patterns that John Coltrane would use decades later. Ellington also shows off his Harlem stride credentials in a quick solo before going into an orchestrated sax soli, one of the first of its kind. After a blaring shout chorus, the piece recalls the A section before Harry Carney caps everything off with the droning tonic. Diminuendo & Crescendo in Blue. This piece is remarkable for two reasons: Diminuendo & Crescendo in Blue exemplifies Duke’s classical influence, and his desire to write more grandiose pieces with more extended forms. -

THELONIOUS MONK SOLO Monkrar

THELONIOUS MONK - SOLO MONK.rar >>> DOWNLOAD (Mirror #1) 1 / 3 MidwayUSA..is..a..privately..held..American..retailer..of..various..hunting..and..outdoor- related..products.. SoloMonkMP3.rar...Premium..Download..Thelonious..Monk..-..Solo..Monk..(1965)..- ..Fast..&..Anonymous...Add..comment...Your..Name...Your..E-Mail.. Thelonious...Monk.zipka*****l.com132.95...MBThelonious...Monk.zip..... Despite.various.reissue.forma ts.over.several.decades,.the.seven.original.LPs.contained.in.Thelonious.Monk.-.The.Riverside.Tenor.S essions.stood.perfectly.well.on.their... thelonious..monk..-..live..at..the..olympia,paris..may..23rd,1965..-..cd..2.zip. ]Thelonious...Monk.../...S olo...Monk...Solo...Monk...:...Thelonious...Monk.../:...Sbme...Special...Mkts....:...2003/08/19.......Theloni ous...Monk...(p)........... Monk's...Point...10....I...Should...Care...11....Ask...Me...Now...12....These...Fooli sh...Things...(Remind...Me...Of...You)...13....Introspection...14....Darn...That...Dream...15....Dinah...(Ta ke...1)...16....Sweet...And...I..... Solo.Monk.is.the.eighth.album.Thelonious.Monk.released.for.Columbi a.Records.in.1965..The.album.is.composed.entirely.of.solo.piano.work.by.Monk..The.Allmusic.review. by... THELONIOUS..MONK..-..Monk's..Music..-..Amazon.com..Music..Interesting.....Though,..I..will..say.. it's..pretty..remarkable..that..Monk..doesn't..solo..much..on..this..recording.. Solo.Monk. 1964.Solo.M onk..1964.It's.Monk's.Time.(Remastered.2003).1964.Live.At.The.1964.Monterey.Jazz.Festival....1958. Thelonious.In.Action..1957.Thelonious.Monk.With.John... Thelonious..Monk's..solo..recordings..offer..f ascinating..insight..into..the..compositional..and..improvisational..talents..of..one..of..music's..true..o ddballs,..and..Alone..In..San.... My..favourite..album:..Brilliant..Corners..by..Thelonious..Monk.....Thelo nious..Monk's..Brilliant..Corners.....and..Rollins's..lazily..unfolding..and..huge-toned..tenor..solo. -

FRIDAY the 13TH: the MICROS PLAY MONK (Cuneiform Rune 310)

Bio information: THE MICROSCOPIC SEPTET Title: FRIDAY THE 13TH: THE MICROS PLAY MONK (Cuneiform Rune 310) Cuneiform promotion dept: (301) 589-8894 / fax (301) 589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American radio) http://www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ / THELONIOUS MONK / THE MICROSCOPIC SEPTET “If the Micros have a spiritual beacon, it’s Thelonious Monk. Like the maverick bebop pianist, they persevere... Their expanding core audience thrives on the group’s impeccable arrangements, terse, angular solos, and devil-may-care attitude. But Monk and the Micros have something else in common as well. Johnston tells a story: “Someone once walked up to Monk and said, “You know, Monk, people are laughing at your music.’ Monk replied, ‘Let ‘em laugh. People need to laugh a little more.” – Richard Gehr, Newsday, New York 1989 “There is immense power and careful logic in the music of Thelonious Sphere Monk. But you might have such a good time listening to it that you might not even notice. …His tunes… warmed the heart with their odd angles and bright colors. …he knew exactly how to make you feel good… The groove was paramount: When you’re swinging, swing some more,” he’d say...” – Vijay Iyer, “Ode to a Sphere,” JazzTimes, 2010 “When I replace Letterman… The band I'm considering…is the Microscopic Septet, a New York saxophone-quartet-plus-rhythm whose riffs do what riffs are supposed to do: set your pulse racing and lodge in your skull for days on end. … their humor is difficult to resist. -

The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER , President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 4, 2016, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters GARY BURTON WENDY OXENHORN PHAROAH SANDERS ARCHIE SHEPP Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center’s Artistic Director for Jazz. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 2 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, pianist and Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, chairman of the NEA DEBORAH F. RUTTER, president of the Kennedy Center THE 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS Performances by NEA JAZZ MASTERS: CHICK COREA, piano JIMMY HEATH, saxophone RANDY WESTON, piano SPECIAL GUESTS AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE, trumpeter LAKECIA BENJAMIN, saxophonist BILLY HARPER, saxophonist STEFON HARRIS, vibraphonist JUSTIN KAUFLIN, pianist RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA, saxophonist PEDRITO MARTINEZ, percussionist JASON MORAN, pianist DAVID MURRAY, saxophonist LINDA OH, bassist KARRIEM RIGGINS, drummer and DJ ROSWELL RUDD, trombonist CATHERINE RUSSELL, vocalist 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS -

The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBoRAh F. RUTTER, President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 16, 2018, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters TODD BARKAN JOANNE BRACKEEN PAT METHENY DIANNE REEVES Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz. This performance will be livestreamed online, and will be broadcast on Sirius XM Satellite Radio and WPFW 89.3 FM. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 2 THE 2018 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts DEBORAH F. RUTTER, President of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts The 2018 NEA JAzz MASTERS Performances by NEA Jazz Master Eddie Palmieri and the Eddie Palmieri Sextet John Benitez Camilo Molina-Gaetán Jonathan Powell Ivan Renta Vicente “Little Johnny” Rivero Terri Lyne Carrington Nir Felder Sullivan Fortner James Francies Pasquale Grasso Gilad Hekselman Angélique Kidjo Christian McBride Camila Meza Cécile McLorin Salvant Antonio Sanchez Helen Sung Dan Wilson 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 -

The Jazz Record

oCtober 2019—ISSUe 210 YO Ur Free GUide TO tHe NYC JaZZ sCene nyCJaZZreCord.Com BLAKEYART INDESTRUCTIBLE LEGACY david andrew akira DR. billy torn lamb sakata taylor on tHe Cover ART BLAKEY A INDESTRUCTIBLE LEGACY L A N N by russ musto A H I G I A N The final set of this year’s Charlie Parker Jazz Festival and rhythmic vitality of bebop, took on a gospel-tinged and former band pianist Walter Davis, Jr. With the was by Carl Allen’s Art Blakey Centennial Project, playing melodicism buoyed by polyrhythmic drumming, giving replacement of Hardman by Russian trumpeter Valery songs from the Jazz Messengers songbook. Allen recalls, the music a more accessible sound that was dubbed Ponomarev and the addition of alto saxophonist Bobby “It was an honor to present the project at the festival. For hardbop, a name that would be used to describe the Watson to the band, Blakey once again had a stable me it was very fitting because Charlie Parker changed the Jazz Messengers style throughout its long existence. unit, replenishing his spirit, as can be heard on the direction of jazz as we know it and Art Blakey changed By 1955, following a slew of trio recordings as a album Gypsy Folk Tales. The drummer was soon touring my conceptual approach to playing music and leading a sideman with the day’s most inventive players, Blakey regularly again, feeling his oats, as reflected in the titles band. They were both trailblazers…Art represented in had taken over leadership of the band with Dorham, of his next records, In My Prime and Album of the Year. -

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

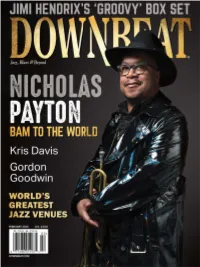

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

[email protected] 1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master Interview Was Provided by the Nati

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. ORRIN KEEPNEWS NEA Jazz Master (2011) Interviewee: Orrin Keepnews (March 2, 1923 – March 1, 2015) Interviewer: Anthony Brown with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: December 10, 2010 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 20 pp. Orrin Keepnews: I wonder if you didn’t—or you could do it when you come back, make sure you didn’t get to show off Lennie. Anthony Brown: The dog? Keepnews: The dog. I remember right now the one strain she couldn’t remember to put in there. He’s part Jack Russell. Brown: Okay. That’s it. Okay so we’ll go from the room tone. Keepnews: Okay so. Brown: Oh we haven’t got it yet. Keepnews: We don’t have it? Brown: Just talk to it. Go ahead. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 1 Keepnews: (Laughs) Brown: Today is December 10th, 2010. This is the Smithsonian/ NEA Jazz Masters Award interview with Orrin Keepnews at his house in El Cerrito, California. And it is a foggy day outside, but a lot of warmth in this house. Good afternoon Orin Keepnews. Keepnews: Good afternoon. Brown: We’re no strangers and so this is, for quite a joy, and a privilege. We’ve done several projects together, well let me just say we’ve done a few projects together, of which I’m very proud. Again, its an honor to be able to conduct this interview with you, to be able to share this time with you so that you could help the listening audience, and the historians, understand—further understand your contribution to this music since our last interview, which was in 1997. -

Jazz Greats: Thelonious Monk

Name Date Jazz Greats: Thelonious Monk Thelonious Monk was one of the creators of the music known as modern jazz. Monk was born in 1917 in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. Around the age of ve, he began to imitate tunes he heard on the family’s player piano. When the family moved to New York, young Thelonious’ mother scraped together the money for a baby grand piano. Now a single mother, she had little extra money, but she managed to pay for the piano lessons Monk began taking at age 11. A serious student, Monk spent much of his time playing or observing other pianists as they played. By the age of 13, Monk was playing with a jazz trio at a local bar and grill. At 16, he left school to pursue music full-time. His rst important gig came in the early 1940s, when he became the house piano player at a club called Minton’s Playhouse. Jazz was undergoing a great period of innovation and change, and Monk was one of the musicians at the center of it all. Beginning in the late 1940s, however, his career declined. A period of poverty, depression, and occasional trouble with the law made life very dicult for Monk and his wife, Nellie. In 1954, Monk recorded his rst solo album, “Pure Monk.” Though his temperament was challenging to many of the other musicians he played with, Monk gained and kept the notoriety he had long deserved. In 1964, he appeared on the cover of Time Magazine, a rare honor, especially for a jazz musician at the time. -

![Morgenstern, Dan. [Record Review: Thelonious Monk: Underground] Down Beat 35:16 (August 8, 1968)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8803/morgenstern-dan-record-review-thelonious-monk-underground-down-beat-35-16-august-8-1968-848803.webp)

Morgenstern, Dan. [Record Review: Thelonious Monk: Underground] Down Beat 35:16 (August 8, 1968)

Ugly Beauty, the ballad (a Monk title, oboe to tell it like it truly is (he is par isn't it?) is bittersweet, of the lineage of 10th Anniversary ticularly effective on this instrument). Ask Me Now, Ruby My Dear, Panonica He takes to the tenor sax on the perky and Crepescule with Nellie-the reflective, Kongsberg. Brooks keeps the kettles hot Summer .Jazz Clinics nostalgic aspects of love. As always, the Last Chance! and the leader charges forth with a very interpretation brings out the melody in gritty solo. Lawson, a man of talent, solos full contour, and Rouse is tuned in. Within days the first sessions of the with verve. Green Chimneys is my favorite, a riff 1968 Summer Jazz Clinics will begin. Lateef's flute is subtly beautiful on the piece; minor with a major bridge. It re Hundreds of musicians and educators longing Stay With Me. Through the minds of Dickie's Dream, the "old" Lester will meet with the best faculty ever technique of overdubbing, he is heard on assembled for a concentrated week of Young classic. Rouse gets off on this. flute and tenor simultaneously on See Line (He, too, so long with Monk, is taken learning jazz, playing jazz, living Woman. Again, the tambourine enhances jazz. There are still openings f~r _all for granted, while little heed is paid to the instruments at each of the five chmcs. this sanctified performance. fact that he has absorbed more about how If it's too late to write, just appear Brother strides in spirited fashion, Lateef Monk's music should be played than any on Sunday at 1 :00 pm at the location weaving urgent patterns. -

Kenny Burrell Kenny Burrell Mp3, Flac, Wma

Kenny Burrell Kenny Burrell mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Kenny Burrell Country: US Released: 1956 Style: Hard Bop, Bop MP3 version RAR size: 1734 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1777 mb WMA version RAR size: 1855 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 480 Other Formats: VQF RA MP2 MP4 WAV FLAC MP1 Tracklist Hide Credits Get Happy A1 Written-By – Arlen*, Koehler* But Not For Me A2 Written-By – Gershwin* Mexico City A3 Written-By – Kenny Dorham Moten Swing A4 Written-By – Bennie Moten, Buster Moten Cheeta B1 Written-By – Kenny Burrell Now See How You Are B2 Written-By – Pettiford*, Harris* Phinupi B3 Written-By – Kenny Burrell How About You B4 Written-By – Lane*, Freed* Companies, etc. Recorded At – Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey Recorded At – Audio-Video Studios Copyright (c) – Liberty Records, Inc. Credits Bass – Oscar Pettiford (tracks: A4, B1, B2, B3, B4), Paul Chambers (tracks: A1), Sam Jones (tracks: A3) Design [Cover Artwork] – Andy Warhol Design [Cover] – Reid Miles Drums – Arthur Edgehill (tracks: A3), Kenny Clarke (tracks: A1), Shadow Wilson (tracks: A4, B1, B2, B3, B4) Liner Notes – Leonard Feather Percussion – Candido (tracks: A1) Piano – Bobby Timmons (tracks: A3), Tommy Flanagan Producer – Alfred Lion Recorded By [Recording By], Mastered By [Mastering By] – Rudy Van Gelder Tenor Saxophone – Frank Foster (tracks: B2, B3, B4), J.R. Monterose (tracks: A3) Trumpet – Kenny Dorham (tracks: A3) Notes Recorded at the Audio-Video Studios, NYC on March 12, 1956 (tracks A4 to B4), at the Rudy Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, NJ, on May 29, 1956 (track A1) and on May 30, 1956 (tracks A2, A3). -

JELLY ROLL MORTON's

1 The TENORSAX of WARDELL GRAY Solographers: Jan Evensmo & James Accardi Last update: June 8, 2014 2 Born: Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, Feb. 13, 1921 Died: Las Vegas, Nevada, May 25, 1955 Introduction: Wardell Gray was the natural candidate to transfer Lester Young’s tenorsax playing to the bebop era. His elegant artistry lasted only a few years, but he was one of the greatest! History: First musical studies on clarinet in Detroit where he attended Cass Tech. First engagements with Jimmy Raschel and Benny Carew. Joined Earl Hines in 1943 and stayed over two years with the band before settling on the West Coast. Came into prominence through his performances and recordings with the concert promoter Gene Norman and his playing in jam sessions with Dexter Gordon.; his famous recording with Gordon, “The Chase” (1947), resulted from these sessions as did an opportunity to record with Charlie Parker (1947). As a member of Benny Goodman’s small group WG was an important figure in Goodman’s first experiments with bop (1948). He moved to New York with Goodman and in 1948 worked at the Royal Roost, first with Count Basie, then with the resident band led by Tadd Dameron; he made recordings with both leaders. After playing with Goodman’s bigband (1948-49) and recording in Basie’s small group (1950-51), WG returned to freelance work on the West Coast and Las Vegas. He took part in many recorded jam sessions and also recorded with Louie Bellson in 1952-53). The circumstances around his untimely death (1955) is unclear (ref.