Dave's Corner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 2019 BLUESLETTER Washington Blues Society in This Issue

LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT Hi Blues Fans, The final ballots for the 2019 WASHINGTON BLUES SOCIETY Best of the Blues (“BB Awards”) Proud Recipient of a 2009 of the Washington Blues Society are due in to us by April 9th! You Keeping the Blues Alive Award can mail them in, email them OFFICERS from the email address associ- President, Tony Frederickson [email protected] ated with your membership, or maybe even better yet, turn Vice President, Rick Bowen [email protected] them in at the April Blues Bash Secretary, Open [email protected] (Remember it’s free!) at Collec- Treasurer, Ray Kurth [email protected] tor’s Choice in Snohomish! This Editor, Eric Steiner [email protected] is one of the perks of Washing- ton Blues Society membership. DIRECTORS You get to express your opinion Music Director, Amy Sassenberg [email protected] on the Best of the Blues Awards Membership, Open [email protected] nomination and voting ballots! Education, Open [email protected] Please make plans to attend the Volunteers, Rhea Rolfe [email protected] BB Awards show and after party Merchandise, Tony Frederickson [email protected] this month. Your Music Director Amy Sassenburg and Vice President Advertising, Open [email protected] Rick Bowen are busy working behind the scenes putting the show to- gether. I have heard some of their ideas and it will be a stellar show and THANKS TO THE WASHINGTON BLUES SOCIETY 2017 STREET TEAM exceptional party! True Tone Audio will provide state-of-the-art sound, Downtown Seattle, Tim & Michelle -

5, 2015 •Marina Park, Thunder

14TH ANNUAL BLUESFEST Your free festival program courtesy of your friends at The Chronicle-Journal JOHNNY REID • JULY 3 - 5, 2015 JULY • MARINA PARK, THUNDER BAY KENNY WAYNE SHEPHERD BAND PAUL RODGERS JOHNNY REID • ALAN FREW • THE PAUL DESLAURIERS BAND • THE BOARDROOM GYPSIES • KENNY WAYNE SHEPHERD BAND • ALAN DOYLE • THE WALKERVILLES • KELLY RICHEY • BROTHER YUSEF • THE BRANDON NIEDERAUER BAND • THE GROOVE MERCHANTS • LOOSE CANNON• PAUL RODGERS • DOYLE BRAMHALL II • WALTER TROUT • THE SHEEPDOGS • THE BROS. LANDRETH • JORDAN JOHN • THE HARPOONIST AND THE AXE MURDERER • THE KRAZY KENNY PROJECT THE VOICE... KEN WRIGHT rock guitar for more than two decades, Kenny Wayne SPECIAL TO THE CHRONICLE-JOURNAL Shepherd will hot wire the marquee on Saturday. Not to be missed, Paul Rogers, the peerless, 90-million-record-sell- What is it about a blues festival, that antsy sense of ing, oh-so-soulful voice of authoritative bands Free, Bad anticipation that we feel? It's a given that the music and Company and Queen will close the festival with the ulti- Ken Wright its performers will be royally entertaining. Yet, we all arrive mate in front man style and swagger on Sunday. with fingers crossed, hoping for that transcendent experi- Newfoundland's unstoppable native son, Alan Doyle, will Has the blues, but in a good way. He writes about them. A veteran director of ence that will reverse the spin of our world if only for an introduce East Coast reels to Top 40 pop with mandolins, fiddles and bouzoukis. Considered by Eric Clapton to be the Thunder Bay Blues Society, Wright puts his writing ability together with an hour to be relived again and again with all who shared it. -

Billboard Top 10 Blues Artist, 2020 IBC Winner, and JUNO Nominee, Canadian Singer/Guitarist JW-Jones Is Known for His High-Energy Shows!

Billboard Top 10 Blues Artist, 2020 IBC Winner, and JUNO Nominee, Canadian singer/guitarist JW-Jones is known for his high-energy shows! * * * * * Fresh off the heels of winning "Best Guitarist" at the 2020 International Blues Challenge in Memphis, popular Canadian blues artist JW-Jones was looking forward to a huge year before COVID-19 hit and halted his tour schedule. “I knew I had to do something productive to stay positive. I turned isolation into inspiration!” said the JUNO-nominated Jones, whose searing axemanship has been praised in recent years by legendary blues artists Buddy Guy and Chuck Leavell (The Rolling Stones). From original music to previously unreleased songs, "this album sounds bigger and wider-than-ever” says Jones, "thanks to Eric Eggleston of Johnny Hall Productions, who has wicked ears and a fresh approach to production”. It features a 17-piece band with a 13-piece horn section, plus additional tracking of vocals, guitars, and studio effects that led to a most appropriate album title, Sonic Departures. High production values didn't take priority over keeping it real for this Ottawa- born artist. "Every single guitar solo on this record, with the exception of one, was recorded in one take, and it was the first-and-only take, with the band and horn section performing together in the same room” reveals Jones. In addition to his touring band consisting of Will Laurin (drums/vocals) and Jacob Clarke (upright and electric bass/vocals), Jones brought long-time band-mate Jesse Whiteley back into the fray on keys and to write some of the horn charts. -

2019 Nov 6-10

PROUDLY PRESENTS 2019 Canadian Jazz Festival Nov 6-10 www.jazzyyc.com Instagram @jazz_yyc Twitter @Jazz_YYC Facebook @JazzYYC JAZZYYC Canadian Festival JazzYYC Canadian PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Festival Team Welcome to the 6th edition of the JazzYYC Canadian Artistic Producer Festival! JazzYYC is pleased to present our most diverse Kodi Hutchinson fall program yet, made possible by our growing base Operations of sponsors, donors and members, and supported Jason Valleau by our wonderful JazzYYC volunteers. Special thanks Operations Coordinator go to the Alberta Foundation for the Arts, Calgary Arts Lucy Pasternak Development, Canada Council for the Arts, TD, Inglewood Marketing & Publicity BIA and the Calgary Public Library. BLP Arts Marketing JazzYYC strives to bring Calgary audiences the best of jazz in all of its forms so that we Social Media can build a vibrant scene in this city. Likewise, it’s our pleasure to provide a stage for Angela Wrigley, Mandy Morris the next generation of jazz artists honing their skills in the JazzYYC Youth Lab Band. As Website & Newsletter Management always, the festival brings Music Mile alive on Sunday afternoon when JazzWalk brings Ty Bohnet live jazz to the shops, restaurants and Brew pubs in Inglewood and this year we are Creative Director excited to include the Central Library in our JazzWalk series. Sharie Hunter Production Coordinator Your support as audience, through our membership program, donors, sponsors and Steven Fletcher volunteers keeps the spirit and sound of jazz alive and growing in Calgary! JazzYYC Board Gerry Hebert of Directors President, JazzYYC Gerry Hebert - President ARTISTIC PRODUCER’S MESSAGE Ken Hanley - Vice President Welcome to our annual JazzYYC Canadian Festival! Malcolm McKay - Treasurer Starting out as a small group of community events Shannon Matthyssen - Secretary back in 2012, it has been wonderful being a part of the Debra Rasmussen - Past President evolution of this Festival. -

Etta James 2012

February 2012 www.torontobluessociety.com Published by the TORON T O BLUES SOCIE T Y since 1985 [email protected] Vol 28, No 2 1938 Etta James 2012 CANADIAN PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT #40011871 MBA winners Event Listings John’s Blues Picks & more Loose Blues News TORON T O BLUES SOCIE T Y Upcoming TBS Events 910 Queen St. W. Ste. B04 Toronto, Canada M6J 1G6 Tel. (416) 538-3885 Toll-free 1-866-871-9457 Email: [email protected] Website: www.torontobluessociety.com MapleBlues is published monthly by the Toronto Blues Society ISSN 0827-0597 2012 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Derek Andrews (President), Jon Arnold (Executive), Gord Brown, Lucie Dufault (Secretary), Sharon Evans, Sarah French, Julian Fauth and Paul Reddick will appear Thursday, February 2 at the Gladstone Sharon Kate Grace, Michael Malone (Treasurer), Hotel's Melody Bar as part of the Toronto Blues Society First Thursday series. The Ed Parsons (Executive), Norman Robinson, Toronto Blues Society presents the best in blues talent the first Thursday of each month Paul Sanderson, Mike Smith (Executive), John at the recently renovated Melody Bar in The Gladstone Hotel. Performances are Valenteyn (Executive) free to the public and begin at 9pm. The next show in the series is on March 1, and Musicians Advisory Council: Lance Anderson, features a performance by Rick Taylor and Carlos del Junco. Check back soon Brian Blain, Gary Kendall, Al Lerman, Lily Sazz, to find out about upcoming performances including Layla Zoe (April 5), and Mark Stafford, Suzie Vinnick Morgan Davis (May 3). Membership Committee: Mike Malone, Lucie Default, Gord Brown, Sarah French, Mike Smith, Debbie Brown, Ed February 11, 1pm-4pm at Lula Lounge (1585 Dundas St Parsons, Norm Robinson, Rick Battision, W) - Digital Dollars: The second Digital Dollars seminar. -

Guitar Mikey Timeline

GUITAR MIKEY TIMELINE 1969 At the age of 5 receives a stack of 45 rpm records. By the age of 6 he finds himself recording himself singing along the records on his dad’s cassette recorder. Songs included “Kansas City” by Trini Lopez. 1976 First Television Appearances At Age 11 Mike McMillan AKA Guitar Mikey at age 11 starts The Young Canadian Blues Band. He makes several appearances with the 3 member band on a local cable show performing some 50's rock'n'roll classics as well as Johnny Winter's "Mean Town Blues". At age 11 Mike attends a Muddy Waters concert by himself. His father returns at the end of the show to pick him up. He is nowhere to be found. Eventually as Mike's dad continues to circle the auditorium he finds Mike exiting the stage door where he had been hanging out with the man himself, Muddy Waters. First Working Band Mike had just turned 12 when he joined his first working band "Phoenix". They would play local high school dances. He would continue performing as a guitar player playing in rock bands while all the time really wanting to play blues. 1980 Steel City Blues Band Mike realized that if he was going to play blues, he would have to front a band as the singer. So he began to sing blues imitating his childhood idol Johnny Winter. The familiar growling style would work for the time being. However Mike's singing would eventually grow into something all his own. He started The Steel City Blues Band. -

WBB One Sheet 2018

W A Y N E B A K E R B R O O K S N O W A V A I L A B L E F O R B O O K I N G iTunes Born and Raised in Chicago, Illinois Wayne Baker Brooks is considered one of today's top guitarists who's signature style combines powerful vocals with liquid fire guitar playing that honors his rich blues heritage yet effortlessly expands the boundaries of the genre. In 1997 he formed the Wayne Baker Brooks Band. In 1998 he co-authored "Blues for Dummies" with his father Lonnie Brooks and Rocker Cub Koda. He soon joined his father's band (Lonnie Brooks Blues Band) as his rhythm guitarist then quickly became bandleader & musical director. With the release of his acclaimed debut CD "Mystery" "an album that brilliantly draws on blues, blues rock, soul, funk and beyond" says All Music Guide, "Mystery" received multiple awards, accolades, and praise from the music world. Along with releasing "Blues for Dummies" & "Mystery" he was soon touring the world and featured on national TV programs (including CNN's "Showbiz"), as well as endless national radio programs, performing at the 2003 Major League Baseball All- Star Game in Chicago, and even performing for First Lady Hilary Rodham Clinton at Chess Studios (Willie Dixon Blues Heaven Foundation) with legends Bo Diddley, KoKo Taylor, & Lonnie Brooks. At the conclusion of the band's explosive set, Hillary stated, "My husband is going to be so jealous he missed this!". Wayne Baker Brooks and his band continue to record, make appearances on TV, and play the world over with WBB's signature top-shelf brand of guitar playing and a live show that should not be missed. -

Fall 2010 E-News-FINAL

Ottawa BLUES Society Got Blues? Join the Club! Road to the IBC in Memphis—Feb 1-5, 2011 Fall 2010 Al Wood & the Woodsmen join Brandon Agnew & Benny Gutman on the ‘Road to Inside the e-news Memphis’. Brandon & Benny were the successful Solo/Duo competitors at the ♫ Road to Memphis Ottawa Blues Society’s first ever Solo/Duo ♫ OBS Update blues challenge held on Wednesday, ♫ September 8. Al Wood & the Woodsmen Blues Summit & Maple Blues advanced to the finals from the 3rd Band Awards Qualifying Round, held Wednesday, September 22. Friday, September 24, six ♫ Blues Foundation News finalist bands played smokin’ sets at Tucson’s, and Al & his Woodsmen got the ♫ Blues News & Random nod from the finals judges. The other finalists included Bluestone, Lil’ Al’s Notes Combo, Steve Groves & the Wit Shifters, the Brothers Chaffey and Jeff Rogers ♫ Summer Festival Photos & the All Day Daddies. Throughout the ♫ DVD Review competitions, each ♫ Amanda’s Rollercoaster performance was judged by the same criteria as is used at the International Blues Challenge in Memphis. Bands played for 25 minutes, solos & duos for 20 minutes. Cover charges and impressive raffle draws raised a total of $5,200 as financial support for travel and accommodation expenses for the winners. The Ottawa Blues Society extends a special thank you to the following who contributed hugely to the success of the 2010 Road to Memphis: ♪ from the OBS - our volunteers, and our corporate sponsors, for their donations and support; ♪ from Tucson’s - Steve Ross, Jim Jones, our hostess Jennifer -

Shopping > Entertainment > Recordings > Music > Specialty

Google Directory - Shopping > Entertainment > Recordings > Music > Specialty Directory Help Search only in Specialty Search the Web Specialty Shopping > Entertainment > Recordings > Music > Specialty Go to Directory Home Categories Alternative (19) Flamenco (5) Reggae (21) Audiophile (15) Folk (29) Regional and Ethnic (237) Backing Tracks (15) Gymnastics (7) Rhythm and Blues, Funk, and Ballet (12) Hip-Hop (24) Soul (16) Barbershop Harmony (3) Holiday (12) Rock (100) Blues (13) Imports (31) Ska (4) Celtic (24) Independent Artists (68) Soundtracks (10) Cheerleading (9) Jazz (48) TV Compilations (6) Children (88) Karaoke (107) Urban, Dance, and Christian (84) Military (6) Electronica (195) Classical and Early (95) Native American (29) Videos (16) Country (18) New Age (74) Vintage (10) Experimental, Noise, and Progressive Rock (16) Vocal (1) Ambient (41) Punk and Hardcore (48) Weddings (18) Fitness (11) White Power (9) Related Categories: Arts > Music > Collecting (244) Arts > Music > Record Labels (1111) Arts > Music > Styles (37378) Web Pages Viewing in Google PageRank order View in alphabetical order Cadence Music Sales - http://www.cadencebuilding.com/ Large selection of mostly obscure jazz, especially avant-garde, and blues titles from hundreds of labels. Order by phone, fax, email, or mail. Forced Exposure - http://www.forcedexposure.com/ Large selection of underground music CDs and records, including reissues, from around the world. Browse by artist or label or download the catalog. http://directory.google.com/Top/Shopping/Entertainment/Recordings/Music/Specialty/ (1 of 8)9/24/2004 6:45:49 AM Google Directory - Shopping > Entertainment > Recordings > Music > Specialty Arhoolie Records/Down Home Music - http://www.arhoolie.com Hard-to-find country, bluegrass, and old time recordings along with other American genres and world music CDs, videos, magazines, and books. -

A Conceptual Canadian Blues Festival Somehot Peppersfrom Midwinter

Canadian Folk Music BUUEllN 31.2 (1997) ...3 A Conceptual Canadian Blues Festival somehot peppersfrom midwinter I had early lessonsin marginalization.As a little boy, I was North America, and the blues, we should all recognize, is in fascinatedby the culture of Native Americansand Canadians,a Canada.To refresh your memory, some months ago we pub- preoccupationwhich is less common than one might think. lished Dave Spalding'sreview of a set of recordingsby Jackson Among the kids I shareda block with, army was consideredthe Delta, a mostly acousticblues trio from Peterborough.2In that grownup, acceptablegame, and anything else was likely to be review, Dave commentedon the prevalenceof Americanplaces called babyish (a word I don't supposeI've heard spoken for and themesin the material before him and asked,"Don't Cana- nearly two quartersof a century). Cowboystended to be passe; dian situationsinspire blues players?" As I set that issueup, it in the rockin' 50s, the codesof GeneAutry and Roy Rogers,not struck me that this might be the excusefor a specialissue some to mention the latter's relatively delicate good looks, left their time. When Rick Fines, of JacksonDelta, respondedwith some machismosuspect. Of course,if I'd fastenedupon them, at least valid, intelligent thoughts on the matter (Bulletin 30.4, I'd have been interestedin white people. The slanderthat was December1996), John and I confirmed the plan. laid on me was, "Georgewants to be an Indian when he grows What follows does not pretendto be exhaustiveor defini- up." Think about it-not only did I haveto defendmy choiceof tive, nor shoulda readerassume that it is basedupon exhaustive obsessions,I had to defendmyself againstthe claim that I didn't researchon our part. -

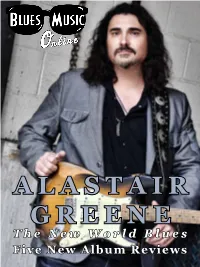

The New World Blues Five New Album Reviews Order Today Click Here! Four Print Issues Per Year

ALASTAIR GREENE The New World Blues Five New Album Reviews Order Today Click Here! Four Print Issues Per Year Every January, April, July, and October get the Best In Blues delivered right t0 you door! Artist Features, CD, DVD Reviews & Columns. Award-winning Journalism and Photography! Order Today ALASTAIR GREENE Click THE NEW WORLD BLUES Here! H NEW ALBUM H Produced by Tab Benoit for WHISKEY BAYOU RECORDS Available October 23, 2020 “Fronting a power blues-rock trio, guitarist Alastair Greene breathes in sulfuric fumes and exhales blazing fire.” - Frank John Hadley, Downbeat Magazine “Greene is a no frills rock vocalist. His fiery solos prove him a premier shredder who will appeal to fans of Walter Trout, Joe Bonamassa, and Albert Castiglia.” - Thomas J Cullen III, Blues Music Magazine “On THE NEW WORLD BLUES, Alastair makes it clear why he is a ‘guitar player’s guitar player,’ and this recording will surely leave the Alastair Greene stamp on the Blues Rock World.” - Rueben Williams, Thunderbird Management, Whiskey Bayou Records alastairgreene.com whiskeybayourecords.com BLUES MUSIC ONLINE November 11, 2020 - Issue 21 Table Of Contents 06 - ALASTAIR GREENE The New World Blues By Art Tipaldi & Jack Sullivan 18 - FIVE NEW CD REVIEWS By Various Writers 28 - FIVE BOOK REVIEWS 39 - BLUES MUSIC SAMPLER DOWNLOAD CD Sampler 26 - July 2020 PHOTOGRAPHY © LAURA CARBONE COVER PHOTOGRAPHY © COURTESY ALASTAIR GREENE Read The News Click Here! All Blues, All The Time, AND It's FREE! Get Your Paper Here! Read the REAL NEWS you care about: Blues Music News! -

Brevard Live August 2014

Brevard Live August 2014 - 1 2 - Brevard Live August 2014 Brevard Live August 2014 - 3 4 - Brevard Live August 2014 Brevard Live August 2014 - 5 6 - Brevard Live August 2014 Content August 2014 SURFING FESTIVAL FEATURES The 29th annual NKF Rich Salick Pro-Am Surf Festival is the largest surfing charity THE BMA SHOW competition in the world, featuring profes- BMA producer Ana Kirby introduces the sional and amateur surfing competitions. Columns program of the 2014 Brevard Live Music This event is held each Labor Day Week- Awards Show. Get a sneak preview of the end at the Cocoa Beach Pier. Charles Van Riper glamorous evening of celebrating our mu- Page 21 sic scene in Brevard County. 22 Political Satire Page 12 BREVARD EATZ Calendars KING CENTER SEASON OF STARS We visited New England Eatery where 25 Live Entertainment, Rock, Pop, Jazz, Blues, Soul, the Famous you can eat the freshest seafood - you Concerts, Festivals and the Legendary - the King Center offers guessed it - New England style. The res- a season of top-notch entertainment. Check taurant is a favorite among locals and Outta Space it out and buy your tickets early. tourists alike. 30 by Jared Campbell Page 16 Page 38 Local Lowdown BREVARD COMEDY by Steve Keller HERE’S TO THE 80s 33 What’s trending? Steve Keller needed a good laugh so he Do you want to time-travel? How about decided to visit Open Mike’s to check out going back to the 80s, when the baby WTF Wednesday, an open mic comedy boomers were going wild with clothes, Knights After Night night where Brevard comics vie for stage hair styles, and - believe or not - new tech- 44 Hot spots, events, time.