Ions in a Penning Trap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Restricted Energy Transfer in Laser Desorption of High Molecular Weight Biomolecules

Scanning Microscopy Volume 5 Number 2 Article 3 4-20-1991 Restricted Energy Transfer in Laser Desorption of High Molecular Weight Biomolecules Akos Vertes University of Antwerp, Belgium, [email protected] Renaat Gijbels University of Antwerp, Belgium Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/microscopy Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Vertes, Akos and Gijbels, Renaat (1991) "Restricted Energy Transfer in Laser Desorption of High Molecular Weight Biomolecules," Scanning Microscopy: Vol. 5 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/microscopy/vol5/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Dairy Center at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scanning Microscopy by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Scanning Microscopy, Vol. 5, No. 2, 1991 (Pages 317-328) 0891-7035/91$3.00+ .00 Scanning Microscopy International, Chicago (AMF O'Hare), IL 60666 USA RESTRICTED ENERGY TRANSFER IN LASER DESORPTION OF HIGH MOLECULAR WEIGHT BIOMOLECULES Akos Vertes* and Renaat Gijb els Departm ent of Chemistry, University of Antwerp (U.I.A.), Universiteitsplein 1, B-2610 Wilrijk (Belgium) (Received for publication November 15, 1990, and in revised form April 20, 1991) Abstract Introdu ction Producing ions from large molecules is of distin With the growing importan ce of biomedical investi guished importance in mass spectrometry. In our present gations in organic analysis the emphasis has been shift study we survey different laser desorption methods in ing to the detection and structure determination of ever view of their virtues and drawbacks in volatilization and larg er and more complex molecules. -

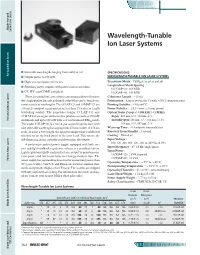

Wavelength-Tunable Ion Laser Systems

38Ch_AirCooledIonLsrs_f_v3.qxd 6/8/2005 11:19 AM Page 38.4 Diode-Pumped Solid-State Lasers Wavelength-Tunable Ion Laser Systems $ Selectable wavelengths ranging from violet to red SPECIFICATIONS: Air-Cooled Ion Lasers Air-Cooled $ Output power to 195 mW WAVELENGTH-TUNABLE ION LASER SYSTEMS $ Highest output power for its size Transverse Mode : TEM00 (except as noted) Longitudinal Mode Spacing : $ Switching power supplies with power-factor correction 35 (X)AP 321: 469 MHz $ CE, IEC, and CDRH compliant 35 (X)AP 431: 349 MHz These air-cooled ion laser systems are compact devices that pro- Coherence Length : ~10 cm duce high-quality, linearly polarized output that can be tuned over Polarization : Linear (vertical85°) with >250:1 extinction ratio a wide variety of wavelengths. The 35 LAP 321 and 35 MAP 321 are Pointing Stability : <30 mrad°C extremely compact argon-ion lasers, less than 15 inches in length Power Stability : 80.5% over a 2-hour period (excluding cables). The somewhat longer 35 LAP 431 and Optical Noise (%p-p @ <100 kHz / <1 MHz) : 35 MAP 431 are argon-ion lasers that produce as much as 195 mW Argon: 488 nm, 4 / 6; 514 nm, 4 / 6 Helium Cadmium Lasers multimode and up to 130 mW with a clean Gaussian TEM00 mode. Argon/Krypton: 488 nm, 5 / 7; 514 nm, 6 / 10; The model 35 KAP 431 is a mixed-gas (argon/krypton) laser with 568 nm, 3 / 6; 647 nm, 5 / 8 nine selectable wavelengths ranging from 476 nm (violet) to 676 nm Warm-up Time : <15 minutes from cold start (red). -

Argon-Ion and Helium-Neon Lasers

Argon-Ion and Helium- Neon Lasers The one source for gas lasers What makes Lumentum the choice for argon-ion and helium-neon (HeNe) lasers? Whether you are involved in medical research, semiconductor manufacturing, high-speed printing, or Your Source for another demanding application, we have the expertise, commitment, and technology to ensure you get the best solution for your need. With more than 35 years of experience, we have an unmatched Successful gas laser production requires extraordinary care understanding of the gas laser market. That understanding has during the manufacturing process. Every individual throughout led us to devote extensive resources to help establish a premier, each production stage, from engineering and procurement to Gas Lasers high-volume manufacturing facility. Located in Thailand, the manufacturing and quality control, is attuned to the highly facility produces lasers of the highest standard. And we maintain sensitive nature of the applications for which these products are that standard through regional quality management, on-site used. Consequently, we can assure the steady supply of quality supplier quality engineering, and regular quality audits. products to our customers around the globe. Our products are being used in customers’ new systems and as replacement components in the large installed base of existing systems. 2 3 Key Gas Laser Applications Known for their longevity and predictable electrical and optical performance characteristics, our lasers are being used in a wide variety of applications. Medical Research University, medical, and government laboratories on the cusp of new discoveries rely on instruments designed with Lumentum argon-ion and HeNe lasers for cell mapping, genome analysis, and DNA sequencing. -

Air-Cooled Argon-Ion Laser Heads in Cylindrical Package 2213 Series

Air-Cooled Argon-Ion Laser Heads in Cylindrical Package 2213 Series www.lumentum.com Data Sheet Air-Cooled Argon-Ion Laser Heads in Cylindrical Package Lumentum’s air-cooled argon lasers are designed for complex, high-resolution OEM applications such as flow cytometry, DNA sequencing, graphic arts, and semiconductor inspection. Symmetric design and axial airflow in the cylindrical argon ion Key Features laser heads provide the best mechanical package to ensure • Integral-mirror, metal-ceramic construction optimum beam-pointing stability and fast warm-up. Both initial • Hands-off operation installation and routine maintenance are straightforward due to • Ultralow noise tight production control of optical and mechanical tolerances. Blower-induced mechanical vibration is virtually eliminated • Fast warm-up through the use of flexible ducting between the laser head and • Rugged construction blower assembly. • Vibration isolation • Ultrastable resonator and beam pointing Applications • DNA sequencing • Flow cytometry • Confocal microscopy • Semiconductor inspection • Hematology • High-speed printing • Photo processing Compliance • CE per specification EN55011 and EN50082-2 • UL 1950 and 1262 • CDRH 21 CFR 1040.10 • CUL • EN60825-2 • EN60950, IEC 950 and EN61010 www.lumentum.com 2 Air-Cooled Argon-Ion Laser Heads in Cylindrical Package 2213 Series Cylindrical Head (Specifications in inches unless otherwise noted. E-vector is aligned with the umbilical cable.) 11.5 5.37 72.0 MOUNTING AIR INTAKE AREAS 3.88 BEAM AIR .50 OUTPUT EXHAUST 1.0 4X 4-40 -

CW Ndryag LASER Martin David Dawson, B.Sc

CHARACTERISATION AND APPLICATION OF A MODE-LOCKED (MODE-LOCKED/Q-SWITCHED) C.W. NdrYAG LASER Martin David Dawson, B.Sc., A.R.C.S. A Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London and for the Diploma of Membership of Imperial College Optics Group Blackett Laboratory Imperial College of Science and Technology M a r c h 1985 London SW7 2BZ DEDICATION To Mam, Dad and Pam ABSTRACT A synchronously operated (Synchroscan) picosecond streak camera has been used in a direct time-resolved study of laser emission from a GaAs/(GaAl)As double heterostructure laser pumped by 514-nm Ar ion laser pulses of duration close to the ^ 60ps Fourier-transform limit. Semiconductor laser pulsewidths as short as 20ps were recorded and the dependence of the temporal characteristics of these pulses on average pump power was investigated. Optical pulses of similar wavelength (532nm) to those obtained from the Ar ion laser, but having considerably shorter duration (^30ps), have been generated by frequency doubling the output of a mode-locked continuous wave (c.w.) Nd:YAG laser using Type II phase matching in a KTiOPOi* (K.T.P.) crystal. High doubling efficiencies (a.10/6 average power conversion) were achieved. These pulses have been used to synchronously pump a Rhodamine 6G jet-stream dye laser, whose performance is compared to its Ar ion 514nm-pumped counterpart. The mode-locked c.w. Nd:YAG laser itself has been thoroughly characterised and various changes made to improve the short and long term stability of the output. Simultaneous Q-switching of this laser at repetition rates ^ 1kHz, both with and without prelasing, has been investigated in detail using streak cameras. -

A Convenient Mode Locking Method of an Ion Laser December 1984

(702) A Convenient Mode Locking Method of an Ion Laser December 1984 Laser Technical Note A Convenient Mode Locking Method of an Ion Laser Shunsuke NAKANISHI*, Hiroshi ITOH*, Koji KONDO* and Yukio FUKUDA** (Received November 19, 1984) This note shows convenient and low cost method for obtaining the mode locked pulses in any commercially available ion laser without the rearrangement of the cavity. In contrast to the usual cases, this mode-locker system consists of two Brewster-cut fused quartz crystals, one of which acts as the acousto-optic modulator and the other as the compensator of the displacement of the laser beam at the acousto-optic modulator. Recentry the picosecond laser has become not be used as the A. O. modulator or such a indispensable to the investigation of the ultrafast modification is very troublesome 3), a home- dynamics in solids, liquids and gases. The designed A.O. modulator should be inserted in generation methods of the picosecond laser the cavity, for example between the laser tube pulses have been developed by using various and the output mirror 4). In this method, means 1,2). A synchronously pumped mode however, it becomes necessary to remove the locked cw dye laser is the most versatile and output mirror from the cavity holder in order to reliable for the generation of the tunable pico- construct the laser cavity because the path of second pulses and easily applicable to obtaining the laser beam suffers the displacement (walk subpicosecond or high power picosecond pulses. off) at the A.O. modulator and the diameter of In the case of the synchronous pumping by an the output mirror is usually too small compared ion laser, it is necessary to achieve the active with the displacement. -

The Future Is Light

IVA- JSPS Seminar The Future is Light The Blue Laser and its Application in Modern Technologies Fredrik Laurell KTH - Royal Institute of Technology 21st Century – the Century of the Photon Photonics – the physical science of light Mastering of the photon relies on scientific progress and innovation in: optics, material science, electrical engineering, nanotechnology, physics, chemistry and biology Where is Photonics important? • Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) • Manufacturing & quality control • Lighting, displays and solar energy • Life Science and healthcare • Security, metrology and sensors • Food safety and production Photonics is everywhere! Photonics is a Key Enabling Technology for Europe as acknowledged by the European Commision in 2009 One of the most important industries for the future with substanitial leverage effect on our economy, workforce and welfare Photonics - scientific progress and innovation in: optics, material science, electrical engineering, nanotechnology, physics and chemistry Lasers • What ? A 50+ old light bulb • How ? •Why should they be blue ? Where ? Basic Laser • Laser medium • Resonator • Pump Atoms in a matrix Energy diagram for a laser stimulated emission a ruby rod mirrors deposited on its end-faces and a flash lamp pump Maiman had to fabricate everything himself Absorption and emission for Cr3+ Laser History • 60-ties laser invented and most effects discovered • 70-ties a solution looking for a problem ... • 80-ties problems discovered! • 90-ties commercial success!! • 00-ties everybodies toy!!! Gas lasers – Diode lasers Diode Pumped Solid-state lasers Fiber lasers 2 kW CO2 Laser The first blue laser Ar-ion laser 0.1 % efficient … The diode laser the smallest and most frequently used laser The diode laser and the optical fiber are the backbone of telecommunication Nobel prize 2000 Zhores I. -

Laser Applications to Medicine and Biology

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF MEDICAL LASERS leactur 7 Dr.khitam Y. Elwasife special Topics 2019-2020 Layout Fundamentals of Laser • Introduction– Properties of Laser Light– Basic Components of Laser– Basic laser operation– Types of Lasers– Laser Applications Principles – of Medical Lasers Types of Medical Lasers– Laser: Medical Applications– Laser: Surgery and Diagnostics– Laser Hazards– Laser Safety– LASER STAND FOR LIGHT AMPLIFICATION BY STIMULATED EMISSION OF RADIATION Introduction LASER Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. •An optical source that emits photons in a coherent beam. •optical lasers, a device which produces any particles or electromagnetic radiations in a coherent state is called “Laser”, e.g., Atom Laser. •In most cases “laser” refers to a source of coherent photons i.e., light or other electromagnetic radiations. It is not limited to photons in the visible spectrum. There are 3 x-ray lasers, infrared lasers, UV lasers etc. Properties of Laser Light • The light emitted from a laser is monochromatic, that is, it is of one color/wavelength. In contrast, ordinary white light is a combination of many colors • Lasers emit light that is highly directional, that is, laser light is emitted as a relatively narrow beam in a specific direction. Ordinary light, such as from a light bulb, is emitted in many directions away from the source. • The light from a laser is said to be coherent, which means that the wavelengths of the laser light are in phase in space and time. Ordinary light can be a mixture of many wavelengths. Ordinary Light vs. Laser Light Ordinar Laser y Light Light Basic Concepts: Laser is a narrow beam of light of a single wavelength (monochromatic) in which each wave is in phase (coherent) with other near it. -

Laser Desorption and Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry of 29-Kda Au:SR Cluster Compounds

Anal. Chem. 2004, 76, 6187-6196 Laser Desorption and Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry of 29-kDa Au:SR Cluster Compounds T. Gregory Schaaff* Chemical Sciences Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37831-6131 Positive and negative ions generated by laser-based for electron microscopy2,3 or bright fluorescent microscopy4-6 ionization methods from three gold:thiolate cluster com- probes. Since the optical and electronic properties of cluster and pounds are mass analyzed by time-of-flight mass spec- nanocrystal compounds are inexorably linked to the size of the trometry. The three compounds have similar inorganic inorganic core, many future applications rely on the ability to core masses (∼29 kDa, ∼145 Au atoms) but different synthesis and isolate compounds with either a narrow core size n-alkanethiolate ligands associated with each cluster distribution or those that are molecularly pure (i.e., one single compound (Au:SR, R ) butane, hexane, dodecane). structure). Giant (nanometer-scale) cluster compounds have been 7 Irradiation of neat films (laser desorption/ionization) and isolated for selected systems recently (e.g., Pd145 metallic clusters 8 films generated by dilution of the cluster compounds in and semiconductor Ag2S cluster compounds ). However, due to an organic acid matrix (matrix-assisted laser desorption/ their inherent compositional and structural complexity, these types ionization) with a nitrogen laser (337 nm) produced of compounds represent a significant challenge for routine distinct ion abundances that are relevant to different analytical chemical techniques, even those developed for other structural aspects of the cluster compound. Laser de- macromolecular systems. sorption/ionization of neat Au:SR compound films pro- Because chemical properties are derived from the organic duces ions consistent with the inorganic core mass (i.e., ligands, one of the unique aspects of the Au:SR compounds devoid of original hydrocarbon content). -

(Ar+) Laser Efficiency Output Power from Argon Laser the Argon Ion

Argon (Ar+) laser efficiency We see from the diagram in figure 1.4 that the lasing energy levels belong to the Argon ion, so the atoms of the gas inside the tube need to be ionized first. As seen in the diagram, the ground state of the laser is at about 16 eV above the ground state of the neutral Argon atom. This is a large amount of energy that must be supplied to the laser, but is not used for creating laser radiation. This "wasted" energy is one of the reasons for the very low efficiency of the Argon laser (0.1%). Output Power from Argon Laser The gain of the active medium in Argon ion lasers is very high, so high power can be achieved from Argon ion lasers (tens of Watts), although as we saw, with low efficiency. The output power increases as a nonlinear function of the current density in the tube. Thus it is common to use narrow tubes (small cross section) and very high currents (100-500 A/cm2). Argon Ion lasers require a separate three phase electrical power lines. The ignition of the Argon Ion laser is done by a pulse of high voltage (about 10 Kilovolts DC) ionizes the argon gas. After ionization, a few hundreds volts DC are maintained across the laser tube. A high DC current (more than 50 Ampers) maintains lasing. Such high current densities create large amounts of heat which must be taken away from the laser. Argon Ion lasers require water cooling. In order to withstand the high temperatures, the laser tube is made from special high melting materials such as Beryllium Oxide. -

The Effect on the Ultrastructure of Dental Enamel of Excimer-Dye, Argon-Ion and CO2 Lasers

Scanning Microscopy Volume 6 Number 4 Article 16 9-23-1992 The Effect on the Ultrastructure of Dental Enamel of Excimer-Dye, Argon-Ion and CO2 Lasers J. Palamara Monash University P. P. Phakey Monash University H. J. Orams Monash University W. A. Rachinger Monash University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/microscopy Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Palamara, J.; Phakey, P. P.; Orams, H. J.; and Rachinger, W. A. (1992) "The Effect on the Ultrastructure of Dental Enamel of Excimer-Dye, Argon-Ion and CO2 Lasers," Scanning Microscopy: Vol. 6 : No. 4 , Article 16. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/microscopy/vol6/iss4/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Dairy Center at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scanning Microscopy by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Scanning Microscopy, Vol. 6, No. 4 , 1992 (Pages 1061-1071) 0891-7035/92$5. 00 +. 00 Scanning Microscopy International, Chicago (AMF O'Hare) , IL 60666 USA THE EFFECT ON THE ULTRASTRUCTURE OF DENTAL ENAMEL OF EXCIMER-DYE, ARGON-ION AND CO2 LASERS J .Palamara·, P.P.Phakey, H.J.Orams and W.A.Rachinger Department of Physics, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria 3168 , Australia (Received for publication February 21, 1992 and in revised form September 23, 1992) Abstract Introduction This sludy aimed to investigate the ultrastructural In recent years there has been renewed interest in changes that occur in dental enamel irradiated with pulsed the application of present day laser technology to clinical excimer-dye, continuous-wave (CW) argon-ion and CW CO2 dcnlal practice (Melcer, et al 1984; Kimura, et al 1983 ; lasers. -

Argon Ion Laser

LASER PHYSICS “Light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation" Methods of Achieving Population Inversion Under normal conditions, more electrons are in a lower energy state than in a higher energy state. Population inversion is a process of achieving more electrons in the higher energy state than the lower energy state. In order to achieve population inversion, we need to supply energy to the laser medium. The process of supplying energy to the laser medium is called pumping. The source that supplies energy to the laser medium is called pump source. The type of pump source used is depends on the laser medium. Different pump sources are used for different laser mediums to achieve population inversion. Some of the most commonly used pump sources are as follows: Optical pumping Electric discharge or excitation by electrons Inelastic atom-atom collisions Thermal pumping Chemical reactions Optical Pumping Light is used to supply energy to the laser medium. An external light source like xenon flash lamp is used to produce more electrons in the higher energy level . When light source provides enough energy to the lower energy state electrons in the laser medium, they jump into the higher energy state E3. The electrons in the higher energy state do not stay for long period. After a very short period, they fall back to the next lower energy state or meta stable state E2 by releasing radiation less energy. The meta stable state E2 has greater lifetime than the lower energy state or ground state E1. Hence, more electrons are accumulated in the energy state E2 than the lower energy state E1.