Women in Reality: a Rhetorical Analysis of Three of Henrik Ibsen’S Plays in Order to Determine the Most Prevalent Feminist Themes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To View/Download the AP List of Free Response Titles

Titles from Open Response Questions* Updated from an original list by Norma J. Wilkerson. Works referred to on the AP Literature exams since 1971 (specific years in parentheses) Please note that only authors were recommended in early years, not specific titles.. A Absalom, Absalom by William Faulkner (76, 00, 10, 12) Adam Bede by George Eliot (06) The Adventures of Augie March by Saul Bellow (13) The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain (80, 82, 85, 91, 92, 94, 95, 96, 99, 05, 06, 07, 08, 11, 13) The Aeneid by Virgil (06) Agnes of God by John Pielmeier (00) The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton (97, 02, 03, 08, 12, 14) Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood (00, 04, 08) All the King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren (00, 02, 04, 07, 08, 09, 11) All My Sons by Arthur Miller (85, 90) All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy (95, 96, 06, 07, 08, 10, 11, 13) America is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan (95) An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser (81, 82, 95, 03) American Pastoral by Philip Roth (09) The American by Henry James (05, 07, 10) Angels in America by Tony Kushner (09) Angle of Repose by Wallace Stegner (10) Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (80, 91, 99, 03, 04, 06, 08, 09, 16) Another Country by James Baldwin (95, 10, 12) Antigone by Sophocles (79, 80, 90, 94, 99, 03, 05, 09, 11, 14) Anthony and Cleopatra by William Shakespeare (80, 91) Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz by Mordecai Richler (94) Armies of the Night by Norman Mailer (76) As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner (78, 89, 90, 94, 01, 04, 06, 07, 09) As You Like It by William Shakespeare (92 05, 06, 10, 16) Atonement by Ian McEwan (07, 11, 13, 16) Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man by James Weldon Johnson (02, 05) The Awakening by Kate Chopin (87, 88, 91, 92, 95, 97, 99, 02, 04, 07, 09, 11, 14) B “The Bear” by William Faulkner (94, 06) Beloved by Toni Morrison (90, 99, 01, 03, 05, 07, 09, 10, 11, 14, 15, 16) A Bend in the River by V. -

Z:\TRANSCRIPTS\2018\0208DED NACIQI REV.Wpd

1 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION + + + + + OFFICE OF POSTSECONDARY EDUCATION + + + + + NATIONAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON INSTITUTIONAL QUALITY AND INTEGRITY + + + + + MEETING + + + + + THURSDAY FEBRUARY 8, 2018 + + + + + The Advisory Committee met in the National Ballroom of the Washington Plaza Hotel located at 10 Thomas Circle, Northwest, Washington, D.C., at 8:30 a.m., Arthur Keiser, Chairman, presiding. 2 MEMBERS PRESENT ARTHUR KEISER, Chairman FRANK H. WU, Vice Chair SIMON BOEHME ROBERTA DERLIN, PhD JOHN ETCHEMENDY, PhD GEORGE FRENCH, PhD BRIAN W. JONES, PhD RICK F. O'DONNELL SUSAN D. PHILLIPS, PhD CLAUDE O. PRESSNELL, JR., PhD ARTHUR J. ROTHKOPF RALPH WOLFF STEVEN VAN AUSDLE, PhD FEDERICO ZARAGOZA, PhD STAFF PRESENT JENNIFER HONG, NACIQI Executive Director HERMAN BOUNDS, Director, Accreditation Group ELIZABETH DAGGETT, Staff Analyst NICOLE HARRIS, Staff Analyst VALERIE LEFOR, Staff Analyst STEPHANIE McKISSIC, Staff Analyst SALLY MORGAN, Office of the General Counsel CHUCK MULA, Staff Analyst 3 ALSO PRESENT SHARON BEASLEY, Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing BARBARA BRITTINGHAM, New England Association of Schools and Colleges ANNE COCKERHAM, Accreditation Commission for Midwifery Education ANTOINETTE FLORES, Center for American Progress BARBARA GELLMAN-DANLEY, Higher Learning Commission RONALD HUNT, Accreditation Commission for Midwifery Education PETER JOHNSON, Accreditation Commission for Midwifery Education CHERYL JOHNSON-ODIM, Higher Learning Commission DAWN LINDSLEY, Oklahoma Department of Career and Technology Education MARCIE MACK, Oklahoma Department of Career and Technology Education BETH MARCOUX, Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education HEATHER MAURER, Accreditation Commission for Midwifery Education CATHERINE McJANNETT, Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing PATRICIA O'BRIEN, New England Association of Schools and Colleges KAREN PETERSON, Higher Learning Commission MARSAL P. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

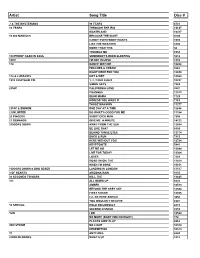

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

A Doll's House Has Been a Trailblazer for Women's Liberation and Feminist Causes Around the World

A Doll’s House Resource Guide – BMCC Speech, Communications and Theatre Arts Department A Doll’s House Resource Guide Spring 2014 Speech, Communications and Theatre Arts Department Theatre Program Borough of Manhattan Community College Dates Wed., April 23rd at 2PM & 7PM Thurs., April 24th at 7 PM Fri., April 25th at 2PM & 7PM Sat., April 26th at 7PM Location BMCC, Main Campus 199 Chambers Street Theatre II Admission is Free Table of Contents Page 2 Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) Norwegian Playwright Page 3 Ibsen around the World Page 4 Director’s Notes on the 1950s Play Adaption Page 5 Advertising from the 1950s Page 6 Ibsen and His Actresses Page 7 Questions for the Audience, Sources, and Further Reading A Doll’s House Resource Guide – BMCC Speech, Communications and Theatre Arts Department Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) Norwegian Playwright Why Ibsen? Henrik Ibsen, with the exception of Shakespeare, is the most frequently produced playwright in the world. He is also universally known as "The Father of Modern Drama" and "The Father of Realistic Drama." For over a century and a half, Ibsen's plays have been renowned for displaying a fierce revolt by the individual against an oppressive middle-class society. Specifically, A Doll's House has been a trailblazer for women's liberation and feminist causes around the world. Portrait of Henrik Ibsen. Photograph by Gustav Borgen . Ibsen Timeline 1828 Born in Skien, a small town in Norway. 1843 At 15 he moves to another small town, Grimstad, and works as an apprentice in a pharmacy. 1851 He moves to Bergen and takes on the position of Artistic Director and Dramatist at the Bergen Theatre. -

Earth Angels Free Edition-0001.Pdf

T T: DEMONIC INVESTIGATOR BOOK FOUR EARTH ANGELS UNLEASHED By Terry Ulick Renegade Company Media © Copyright 2021 with Library of Congress by Terry Ulick ISBN: 978-1-7353192-6-1 Print Edition ISBN: 978-1-7353192-7-8 Electronic Edition Disclaimer: This is a work of fiction, drawn entirely from the imagination of the author. Characters, dialogue, events, locations, and situations are all entirely fictional. Characters are not drawn upon or intended to represent any persons living or dead. Any resemblance to actual events or people is unintentional and entirely coincidental. Proofing and Editing: This book series is exactly as written on an iPhone using the MS Word app, one finger at a time using only the spell checker. That is a critical part of the story. This book has retained the files, as written, and did not go through a separate party to change anything written. Please accept errors in punctuation and style. The book remains the result of pure inspiration, letting the original flow of ideas be seen by the reader. The author beleives the errors are clues to be preserved. What you see is actual inspiration without conventional authoring. It is as it was at the time of writing and has not been changed from that moment. First printing: March 2021 by Renegade Company Media Renegade Company Media is owned by Renegade Company LLC Type: Text is Garamond Pro, 12 point. Book designed and presented by: Terry Ulick Published by: Renegade Company Media PO Box 271193 Littleton, CO 80127 www.renegadecompany.com 2 T: DEMONIC INVESTIGATOR BOOK FOUR EARTH ANGELS UNLEASHED Adult Content Warning: Reader Discretion Strongly Advised. -

Marygold Manor DJ List

Page 1 of 143 Marygold Manor 4974 songs, 12.9 days, 31.82 GB Name Artist Time Genre Take On Me A-ah 3:52 Pop (fast) Take On Me a-Ha 3:51 Rock Twenty Years Later Aaron Lines 4:46 Country Dancing Queen Abba 3:52 Disco Dancing Queen Abba 3:51 Disco Fernando ABBA 4:15 Rock/Pop Mamma Mia ABBA 3:29 Rock/Pop You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:31 Rock AC/DC Mix AC/DC 5:35 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC 3:51 Rock/Pop Thunderstruck ACDC 4:52 Rock Jailbreak ACDC 4:42 Rock/Pop New York Groove Ace Frehley 3:04 Rock/Pop All That She Wants (start @ :08) Ace Of Base 3:27 Dance (fast) Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 3:41 Dance (fast) The Sign Ace Of Base 3:09 Pop (fast) Wonderful Adam Ant 4:23 Rock Theme from Mission Impossible Adam Clayton/Larry Mull… 3:27 Soundtrack Ghost Town Adam Lambert 3:28 Pop (slow) Mad World Adam Lambert 3:04 Pop For Your Entertainment Adam Lambert 3:35 Dance (fast) Nirvana Adam Lambert 4:23 I Wanna Grow Old With You (edit) Adam Sandler 2:05 Pop (slow) I Wanna Grow Old With You (start @ 0:28) Adam Sandler 2:44 Pop (slow) Hello Adele 4:56 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop (slow) Chasing Pavements Adele 3:34 Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Rolling in the Deep Adele 3:48 Blue-eyed soul Marygold Manor Page 2 of 143 Name Artist Time Genre Someone Like You Adele 4:45 Blue-eyed soul Rumour Has It Adele 3:44 Pop (fast) Sweet Emotion Aerosmith 5:09 Rock (slow) I Don't Want To Miss A Thing (Cold Start) -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

A Doll's House

A DOLL'S HOUSE by Henrik Ibsen ACT I. ACT II. ACT III. DRAMATIS PERSONAE Torvald Helmer. Nora, his wife. Doctor Rank. Mrs Linde. Nils Krogstad. Helmer's three young children. Anne, their nurse. A Housemaid. A Porter. [The action takes place in Helmer's house.] A DOLL'S HOUSE ACT I [SCENE.--A room furnished comfortably and tastefully, but not extravagantly. At the back, a door to the right leads to the entrance-hall, another to the left leads to Helmer's study. Between the doors stands a piano. In the middle of the left-hand wall is a door, and beyond it a window. Near the window are a round table, arm-chairs and a small sofa. In the right-hand wall, at the farther end, another door; and on the same side, nearer the footlights, a stove, two easy chairs and a rocking-chair; between the stove and the door, a small table. Engravings on the walls; a cabinet with china and other small objects; a small book-case with well-bound books. The floors are carpeted, and a fire burns in the stove. It is winter. A bell rings in the hall; shortly afterwards the door is heard to open. Enter NORA, humming a tune and in high spirits. She is in outdoor dress and carries a number of parcels; these she lays on the table to the right. She leaves the outer door open after her, and through it is seen a PORTER who is carrying a Christmas Tree and a basket, which he gives to the MAID who has opened the door.] Nora. -

Lyrics for Songs of Our World

Lyrics for Songs of Our World Every Child Words and Music by Raffi and Michael Creber © 1995 Homeland Publishing From the album Raffi Radio Every child, every child, is a child of the universe Here to sing, here to sing, a song of beauty and grace Here to love, here to love, like a flower out in bloom Every girl and boy a blessing and a joy Every child, every child, of man and woman-born Fed with love, fed with love, in the milk that mother’s own A healthy child, healthy child, as the dance of life unfolds Every child in the family, safe and warm bridge: Dreams of children free to fly Free of hunger, and war Clean flowing water and air to share With dolphins and elephants and whales around Every child, every child, dreams of peace in this world Wants a home, wants a home, and a gentle hand to hold To provide, to provide, room to grow and to belong In the loving village of human kindness Lyrics for Songs of Our World Blue White Planet Words and music by Raffi, Don Schlitz © 1999 Homeland Publishing, SOCAN-New Hayes Music-New Don Songs, admin. By Carol Vincent and Associates, LLC, All rights reserved. From the album Country Goes Raffi Chorus: Blue white planet spinnin’ in space Our home sweet home Blue white planet spinnin’ in space Our home sweet home Home for the children you and me Home for the little ones yet to be Home for the creatures great and small Blue white planet Blue white planet (chorus) Home for the skies and the seven seas Home for the towns and the farmers’ fields Home for the trees and the air we breathe Blue white planet -

University of Warwick Institutional Repository: a Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Phd at The

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/36168 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. Critical and Popular Reaction to Ibsen in England: 1872-1906 by Tracy Cecile Davis Thesis supervisors: Dr. Richard Beacham Prof. Michael R. Booth Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Warwick, Department of Theatre Studies. August, 1984. ABSTRACT This study of Ibsen in England is divided into three sections. The first section chronicles Ibsen-related events between 1872, when his work was first introduced to a Briton, and 1888, when growing interest in the 'higher drama' culminated in a truly popular edition of three of Ibsen's plays. During these early years, knowledge about and appreciation of Ibsen's work was limited to a fairly small number of intellectuals and critics. A matinee performance in 1880 attracted praise, but successive productions were bowdlerized adaptations. Until 1889, when the British professional premiere of A Doll's House set all of London talking, the lack of interest among actors and producers placed the responsibility for eliciting interest in Ibsen on translators, lecturers, and essayists. The controversy initiated by A Doll's House was intensified in 1891, the so-called Ibsen Year, when six productions, numerous new translations, debates, lectures, published and acted parodies, and countless articles considered the value and desirability of Ibsen's startling modern plays. -

A-HA Air Anderson .Paak Angelo Badalamenti, David Lynch Aretha Franklin Basement Beth Hart Boy George & Culture Club Chic

Catalogue Barcode Artist Title Format Info Alternate Mixes of a-ha’s debut album “Hunting High and Low”, first released in the 30th Anniversary deluxe box set, in 2015. It will be the first time these demos appear on vinyl. Limited to 6000 copies worldwide Tracklisting: 1. Take On Me (Video Version) [2015 Remastered], 2. Train Of Thought (Early Mix) [2015 Hunting High And Low / The Early Remastered], 3. Hunting High And Low (Early Mix) [2015 Remastered], 4. The Blue 0349785342 0603497853427 A-HA Alternate Mixes (Vinyl) (Record Store LP Sky (Alternate Long Mix) [2015 Remastered], 5. Living A Boy's Adventure Tale (Early Day 2019) Mix) [2015 Remastered], 6. The Sun Always Shines On T.V. (Alternate Early Mix) [2015 Remastered], 7. And You Tell Me (Early Mix) [2015 Remastered], 8. Love Is Reason (Early Mix) [2015 Remastered], 9. Dream Myself Alive (Early "NYC" Mix) [2015 Remastered], 10. Here I Stand And Face The Rain (Early Mix) [2015 Remastered]. Surfing On A Rocket Limited edition Picture disc from Air. Tracklisting: A1- Surfing Surfing On A Rocket (Vinyl) (Record On A Rocket (Album Version) [3:42], A2 - Surfing On A Rocket (To The Smiling Sun 9029551502 0190295515027 Air 12" Single Remix) Remix – Joakim [6:31], B1 - Surfing On A Rocket (Remixed By Juan MacLean) Store Day 2019) Remix – The Juan MacLean [7:01], B2 - Surfing On A Rocket (Tel Aviv Rocket Surfing Remake) Remix – Nomo Heroes [05:21] Limited to 4000 copies worldwide. Anderson .Paak’s Grammy-nominated “Bubblin” is now available in an exclusive, Bubblin (7" Single) (Record Store Day never-before-seen vinyl colorway made especially for Record Store Day 2019.