Integer Arithmetic and Undefined Behavior in C Brad Karp UCL Computer Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

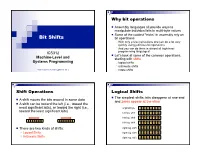

Bit Shifts Bit Operations, Logical Shifts, Arithmetic Shifts, Rotate Shifts

Why bit operations Assembly languages all provide ways to manipulate individual bits in multi-byte values Some of the coolest “tricks” in assembly rely on Bit Shifts bit operations With only a few instructions one can do a lot very quickly using judicious bit operations And you can do them in almost all high-level ICS312 programming languages! Let’s look at some of the common operations, Machine-Level and starting with shifts Systems Programming logical shifts arithmetic shifts Henri Casanova ([email protected]) rotate shifts Shift Operations Logical Shifts The simplest shifts: bits disappear at one end A shift moves the bits around in some data and zeros appear at the other A shift can be toward the left (i.e., toward the most significant bits), or toward the right (i.e., original byte 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 toward the least significant bits) left log. shift 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 left log. shift 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 left log. shift 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 There are two kinds of shifts: right log. shift 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 Logical Shifts right log. shift 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 Arithmetic Shifts right log. shift 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 Logical Shift Instructions Shifts and Numbers Two instructions: shl and shr The common use for shifts: quickly multiply and divide by powers of 2 One specifies by how many bits the data is shifted In decimal, for instance: multiplying 0013 by 10 amounts to doing one left shift to obtain 0130 Either by just passing a constant to the instruction multiplying by 100=102 amounts to doing two left shifts to obtain 1300 Or by using whatever -

Create Union Variables Difference Between Unions and Structures

Union is a user-defined data type similar to a structure in C programming. How to define a union? We use union keyword to define unions. Here's an example: union car { char name[50]; int price; }; The above code defines a user define data type union car. Create union variables When a union is defined, it creates a user-define type. However, no memory is allocated. To allocate memory for a given union type and work with it, we need to create variables. Here's how we create union variables: union car { char name[50]; int price; } car1, car2, *car3; In both cases, union variables car1, car2, and a union pointer car3 of union car type are created. How to access members of a union? We use . to access normal variables of a union. To access pointer variables, we use ->operator. In the above example, price for car1 can be accessed using car1.price price for car3 can be accessed using car3->price Difference between unions and structures Let's take an example to demonstrate the difference between unions and structures: #include <stdio.h> union unionJob { //defining a union char name[32]; float salary; int workerNo; } uJob; struct structJob { char name[32]; float salary; int workerNo; } sJob; main() { printf("size of union = %d bytes", sizeof(uJob)); printf("\nsize of structure = %d bytes", sizeof(sJob)); } Output size of union = 32 size of structure = 40 Why this difference in size of union and structure variables? The size of structure variable is 40 bytes. It's because: size of name[32] is 32 bytes size of salary is 4 bytes size of workerNo is 4 bytes However, the size of union variable is 32 bytes. -

Undefined Behaviour in the C Language

FAKULTA INFORMATIKY, MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Undefined Behaviour in the C Language BAKALÁŘSKÁ PRÁCE Tobiáš Kamenický Brno, květen 2015 Declaration Hereby I declare, that this paper is my original authorial work, which I have worked out by my own. All sources, references, and literature used or excerpted during elaboration of this work are properly cited and listed in complete reference to the due source. Vedoucí práce: RNDr. Adam Rambousek ii Acknowledgements I am very grateful to my supervisor Miroslav Franc for his guidance, invaluable help and feedback throughout the work on this thesis. iii Summary This bachelor’s thesis deals with the concept of undefined behavior and its aspects. It explains some specific undefined behaviors extracted from the C standard and provides each with a detailed description from the view of a programmer and a tester. It summarizes the possibilities to prevent and to test these undefined behaviors. To achieve that, some compilers and tools are introduced and further described. The thesis contains a set of example programs to ease the understanding of the discussed undefined behaviors. Keywords undefined behavior, C, testing, detection, secure coding, analysis tools, standard, programming language iv Table of Contents Declaration ................................................................................................................................ ii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. iii Summary ................................................................................................................................. -

Defining the Undefinedness of C

Technical Report: Defining the Undefinedness of C Chucky Ellison Grigore Ros, u University of Illinois {celliso2,grosu}@illinois.edu Abstract naturally capture undefined behavior simply by exclusion, be- This paper investigates undefined behavior in C and offers cause of the complexity of undefined behavior, it takes active a few simple techniques for operationally specifying such work to avoid giving many undefined programs semantics. behavior formally. A semantics-based undefinedness checker In addition, capturing the undefined behavior is at least as for C is developed using these techniques, as well as a test important as capturing the defined behavior, as it represents suite of undefined programs. The tool is evaluated against a source of many subtle program bugs. While a semantics other popular analysis tools, using the new test suite in of defined programs can be used to prove their behavioral addition to a third-party test suite. The semantics-based tool correctness, any results are contingent upon programs actu- performs at least as well or better than the other tools tested. ally being defined—it takes a semantics capturing undefined behavior to decide whether this is the case. 1. Introduction C, together with C++, is the king of undefined behavior—C has over 200 explicitly undefined categories of behavior, and A programming language specification or semantics has dual more that are left implicitly undefined [11]. Many of these duty: to describe the behavior of correct programs and to behaviors can not be detected statically, and as we show later identify incorrect programs. The process of identifying incor- (Section 2.6), detecting them is actually undecidable even rect programs can also be seen as describing which programs dynamically. -

Data Structures, Buffers, and Interprocess Communication

Data Structures, Buffers, and Interprocess Communication We’ve looked at several examples of interprocess communication involving the transfer of data from one process to another process. We know of three mechanisms that can be used for this transfer: - Files - Shared Memory - Message Passing The act of transferring data involves one process writing or sending a buffer, and another reading or receiving a buffer. Most of you seem to be getting the basic idea of sending and receiving data for IPC… it’s a lot like reading and writing to a file or stdin and stdout. What seems to be a little confusing though is HOW that data gets copied to a buffer for transmission, and HOW data gets copied out of a buffer after transmission. First… let’s look at a piece of data. typedef struct { char ticker[TICKER_SIZE]; double price; } item; . item next; . The data we want to focus on is “next”. “next” is an object of type “item”. “next” occupies memory in the process. What we’d like to do is send “next” from processA to processB via some kind of IPC. IPC Using File Streams If we were going to use good old C++ filestreams as the IPC mechanism, our code would look something like this to write the file: // processA is the sender… ofstream out; out.open(“myipcfile”); item next; strcpy(next.ticker,”ABC”); next.price = 55; out << next.ticker << “ “ << next.price << endl; out.close(); Notice that we didn’t do this: out << next << endl; Why? Because the “<<” operator doesn’t know what to do with an object of type “item”. -

The Art, Science, and Engineering of Fuzzing: a Survey

1 The Art, Science, and Engineering of Fuzzing: A Survey Valentin J.M. Manes,` HyungSeok Han, Choongwoo Han, Sang Kil Cha, Manuel Egele, Edward J. Schwartz, and Maverick Woo Abstract—Among the many software vulnerability discovery techniques available today, fuzzing has remained highly popular due to its conceptual simplicity, its low barrier to deployment, and its vast amount of empirical evidence in discovering real-world software vulnerabilities. At a high level, fuzzing refers to a process of repeatedly running a program with generated inputs that may be syntactically or semantically malformed. While researchers and practitioners alike have invested a large and diverse effort towards improving fuzzing in recent years, this surge of work has also made it difficult to gain a comprehensive and coherent view of fuzzing. To help preserve and bring coherence to the vast literature of fuzzing, this paper presents a unified, general-purpose model of fuzzing together with a taxonomy of the current fuzzing literature. We methodically explore the design decisions at every stage of our model fuzzer by surveying the related literature and innovations in the art, science, and engineering that make modern-day fuzzers effective. Index Terms—software security, automated software testing, fuzzing. ✦ 1 INTRODUCTION Figure 1 on p. 5) and an increasing number of fuzzing Ever since its introduction in the early 1990s [152], fuzzing studies appear at major security conferences (e.g. [225], has remained one of the most widely-deployed techniques [52], [37], [176], [83], [239]). In addition, the blogosphere is to discover software security vulnerabilities. At a high level, filled with many success stories of fuzzing, some of which fuzzing refers to a process of repeatedly running a program also contain what we consider to be gems that warrant a with generated inputs that may be syntactically or seman- permanent place in the literature. -

Bits, Bytes and Integers ‘

Bits, Bytes and Integers ‘- Karthik Dantu Ethan Blanton Computer Science and Engineering University at Buffalo [email protected] 1 Karthik Dantu Administrivia • PA1 due this Friday – test early and often! We cannot help everyone on Friday! Don’t expect answers on Piazza into the night and early morning • Avoid using actual numbers (80, 24 etc.) – use macros! • Lab this week is on testing ‘- • Programming best practices • Lab Exam – four students have already failed class! Lab exams are EXAMS – no using the Internet, submitting solutions from dorm, home Please don’t give code/exam to friends – we will know! 2 Karthik Dantu Everything is Bits • Each bit is 0 or 1 • By encoding/interpreting sets of bits in various ways Computers determine what to do (instructions) … and represent and manipulate numbers, sets, strings, etc… • Why bits? Electronic Implementation‘- Easy to store with bistable elements Reliably transmitted on noisy and inaccurate wires 0 1 0 1.1V 0.9V 0.2V 0.0V 3 Karthik Dantu Memory as Bytes • To the computer, memory is just bytes • Computer doesn’t know data types • Modern processor can only manipulate: Integers (Maybe only single bits) Maybe floating point numbers ‘- … repeat ! • Everything else is in software 4 Karthik Dantu Reminder: Computer Architecture ‘- 5 Karthik Dantu Buses • Each bus has a width, which is literally the number of wires it has • Each wire transmits one bit per transfer • Each bus transfer is of that width, though some bits might be ignored • Therefore, memory has a word size from‘-the viewpoint of -

Fixed-Size Integer Types Bit Manipulation Integer Types

SISTEMI EMBEDDED AA 2012/2013 Fixed-size integer types Bit Manipulation Integer types • 2 basic integer types: char, int • and some type-specifiers: – sign: signed, unsigned – size: short, long • The actual size of an integer type depends on the compiler implementation – sizeof(type) returns the size (in number of bytes) used to represent the type argument – sizeof(char) ≤ sizeof(short) ≤ sizeof(int) ≤ sizeof(long)... ≤ sizeof(long long) Fixed-size integers (1) • In embedded system programming integer size is important – Controlling minimum and maximum values that can be stored in a variable – Increasing efficiency in memory utilization – Managing peripheral registers • To increase software portability, fixed-size integer types can be defined in a header file using the typedef keyword Fixed-size integers (2) • C99 update of the ISO C standard defines a set of standard names for signed and unsigned fixed-size integer types – 8-bit: int8_t, uint8_t – 16-bit: int16_t, uint16_t – 32-bit: int32_t, uint32_t – 64-bit: int64_t, uint64_t • These types are defined in the library header file stdint.h Fixed-size integers (3) • Altera HAL provides the header file alt_types.h with definition of fixed-size integer types: typedef signed char alt_8; typedef unsigned char alt_u8; typedef signed short alt_16; typedef unsigned short alt_u16; typedef signed long alt_32; typedef unsigned long alt_u32; typedef long long alt_64; typedef unsigned long long alt_u64; Logical operators • Integer data can be interpreted as logical values in conditions (if, while, -

Advanced Programming Techniques (Amazing C++) Bartosz Mindur Applied Physics and Computer Science Summer School '20

Advanced Programming Techniques (Amazing C++) Bartosz Mindur Applied Physics and Computer Science Summer School '20 Kraków, 2020-07-16 [1 / 37] www.menti.com/28f8u5o5xr Which programming language do you use the most? cpp h s a b python a c v a y j csharp l b m e s s a 18 [2 / 37] Agenda References C++ history C++11/14 - must be used C++17 - should be used C++20 - may (eventually) be used ... [3 / 37] www.menti.com/uaw75janh7 What is your current knowledge of C++? Core C++ 3.1 C++ STL ! e k e 2.2 i l n o d o N C++ 11/14 G 2.4 C++17 1.4 17 [4 / 37] References and tools [5 / 37] C++ links and cool stu C++ links Online tools ISO C++ Compiler Explorer cpp references cpp insights c & cpp programming cpp.sh #include <C++> repl.it LernCpp.com Quick Bench cplusplus.com Online GDB CppCon piaza.io CppCast codiva.io Bartek Filipek ... Oine tools CMake Valgrind GDB Docker Clang Static Analyzer [6 / 37] Things you (probably) already know well [7 / 37] C++ basics variables conversion and casts references implicit pointers explicit functions static statements dynamic loops exceptions declaration function templates initialization class templates operator overloading smart pointers classes basics of the STL constructors & destructor containers fields iterators methods algorithms inheritance building programs types compilation virtual functions linking polymorphism libraries multiple inheritance tools [8 / 37] www.menti.com/32rn4èy3j What is the most important C++ feature? polymorphism templates encapsulation s r e t n i e inheritance o c p n a s w hardware accessibility i e r e s g s n multithreading i a l generic programming c 8 [9 / 37] C++ history [10 / 37] The Design of C++ The Design of C++, a lecture by Bjarne Stroustrup This video has been recorded in March, 1994 [link] The Design of C++ , lecture by Bjarne Stroustr… Do obejrze… Udostępnij [11 / 37] C++ Timeline [link] [12 / 37] C++11/C++14 [13 / 37] Move semantics Value categories (simplied) Special members lvalue T::T(const T&& other) or T::T(T&& other) T& operator=(T&& other) e.g. -

Malloc & Sizeof

malloc & sizeof (pages 383-387 from Chapter 17) 1 Overview Whenever you declare a variable in C, you are effectively reserving one or more locations in the computerʼs memory to contain values that will be stored in that variable. The C compiler automatically allocates the correct amount of storage for the variable. In some cases, the size of the variable may not be known until run-time, such as in the case of where the user enters how many data items will be entered, or when data from a file of unknown size will be read in. The functions malloc and calloc allow the program to dynamically allocate memory as needed as the program is executing. 2 calloc and malloc The function calloc takes two arguments that specify the number of elements to be reserved, and the size of each element in bytes. The function returns a pointer to the beginning of the allocated storage area in memory, and the storage area is automatically set to 0. The function malloc works similarly, except that it takes only a single argument – the total number of bytes of storage to allocate, and also doesnʼt automatically set the storage area to 0. These functions are declared in the standard header file <stdlib.h>, which should be included in your program whenever you want to use these routines. 3 The sizeof Operator To determine the size of data elements to be reserved by calloc or malloc in a machine-independent way, the sizeof operator should be used. The sizeof operator returns the size of the specified item in bytes. -

Mallocsample from Your SVN Repository

DYNAMIC MEMORY ALLOCATION IN C CSSE 120—Rose Hulman Institute of Technology Final Exam Facts Date: Monday, May 24, 2010 Time: 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. Venue: O167 or O169 (your choice) Organization: A paper part and a computer part, similar to the first 2 exams. The paper part will emphasize both C and Python. You may bring two double-sided sheets of paper this time. There will be a portion in which we will ask you to compare and contrast C and Python language features and properties. The computer part will be in C. The computer part will be worth approximately 65% of the total. Q1-2 Sample Project for Today Check out 29-MallocSample from your SVN Repository Verify that it runs, get help if it doesn't Don’t worry about its code yet; we’ll examine it together soon. Memory Requirements Any variable requires a certain amount of memory. Primitives, such an int, double, and char, typically may require between 1 and 8 bytes, depending on the desired precision, architecture, and Operating System’s support. Complex variables such as structs, arrays, and strings typically require as many bytes as their components. How large is this? sizeof operator gives the number bytes needed to store a value typedef struct { sizeof(char) char* name; int year; sizeof(char*) double gpa; sizeof(int) } student; sizeof(float) sizeof(double) char* firstName; int terms; sizeof(student) double scores; sizeof(jose) student jose; printf("size of char is %d bytes.\n", sizeof(char)); Examine the beginning of main of 29-MallocSample. -

A Cross-Platform Programmer's Calculator

– Independent Work Report Fall, 2015 – A Cross-Platform Programmer’s Calculator Brian Rosenfeld Advisor: Robert Dondero Abstract This paper details the development of the first cross-platform programmer’s calculator. As users of programmer’s calculators, we wanted to address limitations of existing, platform-specific options in order to make a new, better calculator for us and others. And rather than develop for only one- platform, we wanted to make an application that could run on multiple ones, maximizing its reach and utility. From the start, we emphasized software-engineering and human-computer-interaction best practices, prioritizing portability, robustness, and usability. In this paper, we explain the decision to build a Google Chrome Application and illustrate how using the developer-preview Chrome Apps for Mobile Toolchain enabled us to build an application that could also run as native iOS and Android applications [18]. We discuss how we achieved support of signed and unsigned 8, 16, 32, and 64-bit integral types in JavaScript, a language with only one numerical type [15], and we demonstrate how we adapted the user interface for different devices. Lastly, we describe our usability testing and explain how we addressed learnability concerns in a second version. The end result is a user-friendly and versatile calculator that offers value to programmers, students, and educators alike. 1. Introduction This project originated from a conversation with Dr. Dondero in which I expressed an interest in software engineering, and he mentioned a need for a good programmer’s calculator. Dr. Dondero uses a programmer’s calculator while teaching Introduction to Programming Systems at Princeton (COS 217), and he had found that the pre-installed Mac OS X calculator did not handle all of his use cases.