Nitzotzot Min Haner Volume # , June-July 2004 -- Page # 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Memorial Tribute on the First Yahrzeit

THE OHR SOMAYACH TORAH MAGAZINE ON THE INTERNET • www.OHR.Edu O H R N E T SHAbbAT PARSHAT SHEMINI • 20 AdAR II 5774 - MAR. 22, 2014 • VOl. 21 NO. 26 parsha INsIGhTs The prose aNd The passIoN “...a strange fire” (10:1) verything in this world is a physical parable of a spiritu - The halacha is our boundary, and even when one has al reality. Take the computer for example. The entire great passion to seek G-d, one must respect those bound - E“miracle” of the computer is based on the numbers ‘1’ aries. Rabbi Soleveitchik once said that if G-d had not given and ‘0’ placed in ever more complicated and elaborate us explicit permission we would not even be able to pray to sequences. If there’s a ‘0’ where there should be a ‘1’ or vice Him. What arrogance would it be for us to approach G-d? versa, even the simplest program will just not run. It will However, G-d not only allows, but even desires our prayers. probably send one of those delightful error messages like, Still, we must respect the distance that exists between us “Would you like to debug now?” No thank you, I’d like to fin - and G-d. ish this article which is already late! The desire for spirituality is often impatient with details, It’s not immediately apparent but serving G-d is some - rules, regulations and procedures. In looking at the big pic - what like a computer program. ture one might feel that paying attention to the small details In this week’s Torah portion the joyous event of the ded - is just not very important and even distracting. -

Purim, the Holiday That Always Comes Around Terumah and Tetzevah During a Non-Leap Year

BS”D February 19, 2021 Potomac Torah Study Center Vol. 8 #19, February 19, 2021; Terumah 5781; Zachor NOTE: Devrei Torah presented weekly in Loving Memory of Rabbi Leonard S. Cahan z”l, Rabbi Emeritus of Congregation Har Shalom, who started me on my road to learning almost 50 years ago and was our family Rebbe and close friend until his recent untimely death. ____________________________________________________________________________________ Devrei Torah are now Available for Download (normally by noon on Fridays) from www.PotomacTorah.org. Thanks to Bill Landau for hosting the Devrei Torah. ______________________________________________________________________________ Basil and Marlene Herzstein, their daughters Natanya, Yael and Mia, Grandchildren Haviv and Matar, and Basil’s sister Susan Herzstein lovingly sponsor the Devrei Torah for this Shabbat in memory of Basil and Susan’s father, Fred Herzstein, Peretz ben Avraham, whose Yarhzeit is this Shabbat, 8 Adar. ________________________________________________________________________________ From the drama of Aseret Dibrot two weeks ago and 53 mitzvot from (Jewish) law school in Mishpatim, the Torah takes us to the final five portions of Sefer Shemot – four of which consist of detailed instructions for building a Mishkan (space for God’s presence to rest among B’Nai Yisrael) and then covering how the Jews lovingly built the Mishkan following these instructions exactly. I have discussed the Mishkan in my messages the past few years. For a change, I decided to reprint one of these messages (see below) and devote my space to some reflections on Purim, the holiday that always comes around Terumah and Tetzevah during a non-leap year. The death threat to the Jews in Persia at the time of Esther and Mordechai was the first major crisis after the destruction of the first Temple and Babylonian exile (3338). -

Rav Mendel Weinbach זצ"ל Remembering Rav Mendel Weinbach , Zt”L on the First Yahrzeit

Rav Mendel Weinbach זצ"ל Remembering Rav Mendel Weinbach , zt”l On the First Yahrzeit Published by Ohr Somayach Institutions Jerusalem, Israel Published by Ohr SOmayach Tanenbaum College Gloria Martin Campus 22 Shimon Hatzadik Street, Maalot Daphna POB 18103, Jerusalem 91180, Israel Tel: +972-2-581-0315 Email: [email protected] • www.ohr.edu General Editor: Rabbi Moshe Newman Compiled and Edited by : Rabbi Richard Jacobs Editorial Assistant : Mrs. Rosalie Moriah Design and Production: Rabbi Eliezer Shapiro © 2013 - Ohr Somayach Institutions - All rights reserved First Printing - December 2013 Printed in Israel at Old City Press, Jerusalem The following pages represent our humble attempt to pay tribute to our beloved Rosh Hayeshiva, Hagaon HaRav Mendel Weinbach zt”l. Rav Weinbach wasn’t just our Rosh Hayeshiva. He was our father, mentor, advisor, friend, comrade and teacher. This volume is an opportunity for rabbis, staff, students, alumni and friends to share their memories and thoughts about a man who successfully dedicated his entire life to educating his fellow Jew. We hope this will give us an understanding of who Rav Weinbach zt”l was and what he meant to all who had the merit to know him and interact with him. One year has passed. We have come to an even greater awarness how immeasurable our loss is. But our consolation will be in fulfilling the continuity of his legacy of reaching out to our fellow Jews and bringing them closer to Torah. Yehi Zichro Baruch. A Memorial Tribute to Rabbi Mendel Weinbach, zt”l | 5| Chavrusah By RAv NOTA SCHIllER Shlit’a Editor’s Note: The memorial kennes was running late. -

The Baal Teshuva Movement

TAMUZ, 57 40 I JUNE, 19$0 VOLUME XIV, NUMBER 9 $1.25 ' ' The Baal Teshuva Movement Aish Hatorah • Bostoner Rebbe: Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Horowitz• CHABAD • Dvar Yerushalayim • Rabbi Shlomo · Freifeld • Gerrer Rebbe • Rabbi Baruch ·.. Horowitz • Jewish Education Progra . • Kosel Maarovi • Moreshet Avot/ El HaMekorot • NCSY • Neve Yerushalayim •Ohr Somayach . • P'eylim •Rabbi Nota Schiller• Sh' or Yashuv •Rabbi Meir Shuster • Horav Elazar Shach • Rabbi Mendel Weinbach •Rabbi Noach Weinberg ... and much much more. THE JEWISH BSERVER In this issue ... THE BAAL TESHUVA MOVEMENT Prologue . 1 4 Chassidic Insights: Understanding Others Through Ourselves, Rabbi Levi Yitzchok Horowitz. 5 A Time to Reach Out: "Those Days Have Come," Rabbi Baruch Horovitz 8 The First Step: The Teshuva Solicitors, Rabbi Hillel Goldberg 10 Teaching the Men: Studying Gemora-The Means and the Ends of the Teshuva Process, Rabbi Nola Schiller . 13 Teaching the Women: How to Handle a Hungry Heart, Hanoch Teller 16 THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN Watching the Airplanes, Abraham ben Shmuel . 19 0(121-6615) is published monthly, Kiruv in Israel: except Ju!y and August. by the Bringing Them to our Planet, Ezriel Hildesheimer 20 Agudath Israel of America, 5 Beekman Street, New York, N.Y The Homecoming Ordeal: 10038. Second class postage paid Helping the Baal Teshuva in America, at New York, N.Y. Subscription Rabbi Mendel Weinbach . 25 $9.00 per year; two years. $17.50; three years, $25.00; outside of the The American Scene: United States, $10.00 per year. A Famine in the Land, Avrohom Y. HaCohen 27 Single copy, $1.25 Printed in the U.S.A. -

Rav Mendel Weinbach Zt"L

Rav Mendel Weinbach zt"l Founder and Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshiva Ohr Somayach By Dovid Hoffman Wednesday, December 12, 2012 – Yated Neeman USA On Tuesday, thousands of Yeshiva Ohr Somayach alumni felt that they had lost a father when they heard the news of the passing of Rav Mendel Weinbach zt”l, founder and rosh yeshiva of Ohr Somayach. Rav Mendel invested his brilliant mind and feeling heart to draw thousands of Jews back to the joy of Torah learning and practice. As he put it, he wanted to give people a chance to have a chance. Thanks to him, many streets in Eretz Yisroel and worldwide are filled with families who seem indistinguishable from other bnei Torah families anywhere else. Only people who get to know them better realize that these thousands of individuals are the products of Rav Mendel’s hashkafah that to be mekarev a Jew means to transform him into a full-fledged ben Torah. EARLY RESPONSIBILITY TOWARDS OTHERS Rav Mendel was born in Poland in 1933. Not long afterwards, his parents moved to the United States, where his father steadfastly clung to Torah and mitzvos, refusing to work on Shabbos even if this meant working hard at less generous paying jobs to the extent that he was often absent from home when other fathers had already returned from work. His mother made up for this, infusing her young son with a love of Torah and a yearning to delve into its infinite wisdom. While still in public school, Rav Mendel already showed a propensity to care for the welfare of others and not lock himself into his own four amos. -

Thecenterfor

Issue #7 Purim 5756 the Centerfor TORAH STUDIES What does a bright, motivated college grad do if he wants to take a year off from school and learn in Yeshiva? Well, now he can come to “The Center”, Rabbi Pinchas Kantrovitz Ohr Somayach’s new ‘Yeshiva Year Abroad’ program. “The Center” is for guys who’ve tasted the sweetness of Torah, who want to be observant, but who never “Absolute truth is irrational,” said Oberlin solidified their learning skills. College psychology honors graduate Pinchas “We’re excited,” says staff member Saul Mandel. “It’s Kantrovitz. “You have to create your own.” going to be a highly personalized program at a So in June 1982, in search of his ‘own’ truth, Pinchas separate facility. Our goal is to have the guys learning set out around the world on a year’s journey. The Gemmara, Rashi, and Mishna Brura independently in problem was, he only had three months. In one year. Rav Weinbach and Reb Bulman are going to September he was to start a five-year doctoral degree be personally involved.” at one of America’s most competetive and prestigious programs in clinical psychology. A stop in Israel was sandwiched somewhere between Greece and Turkey. At the Kotel Friday night Pinchas ALUMNI SPEAK! was invited for a meal at the home of Rabbi Simcha Wasserman, zatzal. Deeply impressed, Pinchas agreed to Robert (Moshe) Resnick <[email protected]> attend a class in a Yeshiva he’d been hearing about, writes: Ohr Somayach. In October, I got married to Meryl. It’s the second for both of us and we both have young daughters. -

121912 C50-52, 54-55 Community Tribute Weinbach.Qxd

C50 HAMODIA 6 TEVES 5773 DECEMBER 19, 2012 Tribute Harav Mendel Weinbach, zt”l, Rosh Yeshivah, Yeshivas Ohr Somayach BY YEHUDA MARKS Every Jew and His Personal courses dropped, in favor of Avodas Hashem business courses. And the Harav (Chuna) Menachem Harav Weinbach’s strength business student was more Mendel Weinbach, a pioneer of wasn’t just the sheer number of organized in budgeting his time the modern-day baal teshuvah Jews he brought to Torah, but and energy. Backpacking movement and cofounder and how he did it. Harav Weinbach became less popular; dean of Ohr Somayach In- understood that each Jew finds consequently, fewer Jewish stitutions, was niftar last Hashem in his own way, and he backpackers came to the Kosel. Monday after courageously found the way for each Jew to As hashgachah would have it, battling a long and painful find Torah and avodas before Black Monday Ohr illness. He was 79. Hashem — and make it his own. Somayach had already begun Harav Weinbach was the He would quote the bringing students in directly. beloved mentor, father and Rambam, who writes in Hilchos This enabled Harav rebbi to generations of Ohr Avodah Zarah that Avraham Weinbach, who was never Somayach talmidim around the Avinu, the first “kiruv activist,” prepared to take shortcuts, to world. And as a prolific author would answer every person adhere to his shitah of getting and sought-after lecturer for according to his knowledge. the talmidim into the learning of both men’s and women’s groups “Interestingly, we can hear Torah. Unlike the backpackers across the globe, Harav Wein- the same question hundreds of who were sitting on their bach’s zeal and power were a times, and I don’t think I’ve suitcases, Harav Weinbach source of inspiration for given the same answer twice!” could now dedicate his time to thousands of others. -

CHILDR Are the Very Survival of Kial Yisroel Rabbi

THE UNDER· GROUND YESHIVA INGILOH It is located outside the all-new rope. Basements, old farm open 38 new schools in com· development of Giloh, because houses, barns, some with the Thousands more munities across Israel. By no space has been allocated for barest facilities, are the scene of are trying scraping together all available a yeshiva. When you enter the dedicated Rebbes and women resources, we il":l opened low building you must stoop teaching grouPs of children. to get in. four new schools. While we down. The floor is of raw con They are seated on benches And into those dilapidated facili· speak of dollars, we are dealing crete, there is one bathroom, some with the rain dripping from ties are streaming ever more with Jewish souls, with the and no heat. It is divided into 5 the ceiling, the wind blowing children every day. They throw future of our nation, with the rooms, each jam-packed with through broken windows - glances of contempt at the future of Klal Yisroel. children. The chairs and tables freezing in the winter. They are modern edifices of secularism look like they were rescued from sitting and studying our cherish· that stand partly empty. They We could do so the local junk dealer. ed heritage so that Torah should are partly empty because hun· Yet the children are there will continue for their future. But dreds of thousands of secularly much today. ingly. They could be sitting in a while the physical facilities are educated Israelis have made We can change the face of school near their homes, an ul so poor, their Torah and acade· "yerida" to other parts of the Israel. -

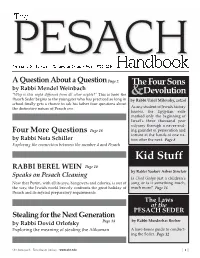

The PESACH Handbook a Question About a Question by Rabbi Mendel Weinbach

PESACHThe Published by Ohr Somayach - Tanenbaum College • Pesach 5770 / 2010 Handbook A Question About a Question Page 2 The Four Sons by Rabbi Mendel Weinbach Devolution “Why is this night different from all other nights?” This is how the & Pesach Seder begins as the youngster who has practiced so long in by Rabbi Uziel Milevsky, zatzal school finally gets a chance to ask his father four questions about the distinctive nature of Pesach eve. As any student of Jewish history knows, the Egyptian exile marked only the beginning of Israel’s three thousand year odyssey through a never-end- Four More Questions Page 18 ing gauntlet of persecution and torture at the hands of one na- by Rabbi Nota Schiller tion after the next. Page 8 Exploring the connection between the number 4 and Pesach Kid Stuff RABBI BEREL WEIN Page 10 by Rabbi Yaakov Asher Sinclair Speaks on Pesach Cleaning Is Chad Gadya just a children’s Now that Purim, with all its joys, hangovers and calories, is out of song or is it something much, the way, the Jewish world bravely confronts the great holiday of much more? Page 16 Pesach and its myriad preparatory requirements. The Laws of the PESACH SEDER Stealing for the Next Generation by Rabbi Dovid Orlofsky Page 14 by Rabbi Mordechai Becher Exploring the meaning of stealing the Afikoman A bare-bones guide to conduct- ing the Seder. Page 12 Ohr Somayach - Tanenbaum College - www.ohr.edu | 1 | The PESACH Handbook A Question About a Question by Rabbi Mendel Weinbach “Why is this night different from all other nights?” his is how the Pesach Seder begins as the young- the Torah’s insistence on our ancestors’ broiling the Pe- ster who has practiced so long in school finally sach sacrifice. -

The Ohr Somayach Alumni Association Brooklyn Beis Midrash

THE OHR SOMAYACH TORAH MAGAZINE ON THE INTERNET • WWW.OHR.EDU SHABBAT PARSHAT BEHA’ALOTCHA • 16 SIVAN 5777 • JUNE 10, 2017 • VOL. 24 NO. 33 PARSHA INSIGHTS by Rabbi yaakov asheR sinclaiR RTAGE RNIGHT E T O H S F “And Aharon did so…” (8:3) tage fright, or as it’s called in hebrew “ aimat ha’tzib - and spontaneity, but i believe, like a gymnast or a musician, bur ” — literally, “fear of the public”, affects nearly when you reach the point where things become automatic, everyone. For some people, having a molar extracted you can go into a “state of flow”. because your mind is swithout anesthesia would be a preferable alternative to relieved of all technical considerations, you can “fly”. having to perform in public. i’m happy to say the speech was well received, but at the The degree of nervousness depends on several factors: end of the day, however much work you put in, finding The size of the audience, the importance of the audience, chein (favor) in peoples’ eyes is something that comes only the amount, or lack, of preparation, the importance of the from G-d. event, and the difficulty of the presentation. in this week’s Torah portion aharon hakohen has a several years ago i was invited to speak at the plenary “command performance” that leaves all teeth-chattering, session of agudat yisrael. i had taken the precaution of fly - palm-sweating appearances in the shade. aharon has to ing to new york a couple of days before the event, having perform in front of the most important “audience” in the remembered a previous experience when i got off the plane, jumped into a taxi at JFk airport, rushed over to universe — G-d. -

121912 C50-52, 54-55 Community Tribute Weinbach.Qxd

C54 HAMODIA 6 TEVES 5773 DECEMBER 19, 2012 Tribute Because It Hurts: Still Crying for Harav Mendel Weinbach, zt”l BY MORDECHAI SCHILLER He didn’t stop while running the post offices used to sell. He filled discussions. the back cover of the magazine. bases to check his standing on every flap of the letter with One day, Harav Nachman I came up with the headline How do you measure the the scoreboard. advice, encouragement, and Bulman, zt”l, walked in, chuck- “Recycle Your Mind!” Reb impact of one person? always with questions — specific ling even more than he usually Mendel read it and shook his And what if that person is a More Than a Partner questions about what I was did. With perfect timing, he head. “You can’t say that!” husband, a father, a grandfather, Maybe the real measure of a doing and how I was doing. waited until his mischievous “Why not?” a neighbor, a friend... and also leader is how he inspires other The letters only stopped smile nailed everyone’s atten- “Essentially, you’re telling happened to be an eminent leaders. when I got married and moved tion. Then he said, “We think people their mind is garbage.” author and Rosh Yeshivah? My brother, ybl”c, Harav Nota back to Eretz Yisrael, and we these boys are not so sophisticat- I saw his point, but still liked Do you keep a running total of Schiller, learned in Yeshiva spoke regularly. After a short ed because they never learned in the concept, so I conducted an talmidim? Like the incessantly Rabbi Chaim Berlin and later time in a kollel, I was hired by the yeshivah, but let me tell you informal focus group. -

Special Message from Roshe Ha'yeshiva

Issue # 1 - Premier Issue! Cheshvan 5755 INTRODUCTORY MESSAGE Special Message from his new communication is intended to serve as a Roshe Ha'yeshiva regular monthly forum for Ohr Somayach alumni T and staff to continue the togetherness we Ma rabbu ma'asecha How wonderous are Your works experienced at Ohr Somayach and as a means for Hashem, Hashem! promoting mutual growth and development. kulam bechochma In Wisdom You have made them asisa. all. Through the Internet we would like to create a virtual Tehillim 104:24 closeness so to speak, through which we could go down to the canteen and keep up on the latest news, ovid Hamelech not only challenged us to go to the Beis Medrash and join a lively discussion, appreciate the brilliant tapestry of Hashem's drop in on a shiur, present halachic or other questions, creation but to find ways of utilizing the and offer our own Torah insights and thoughts for D wisdom of each element of creation for general debate. achieving a closer relationship with its Creator. Greetings from Rabbi Samet Electronic Mail is the newest breakthrough in the sophisticated world of computers and communication. osh Hashana, Yom Kippur, Succos, and Simchas Always on the lookout for opportunities to maintain Torah...this was certainly a busy season for you-- contact with former talmidim and to establish contact R one packed with ruchniyus (spiritual) uplift. with potential new ones, Ohr Somayach has initiated an ambitious state of the art outreach program via the It was a busy season for me as well, seeing that the Internet.