Lime Kilnswereconstructedtoconvertlimestone on Thekingsbridgeestuaryalone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 2021.Cdr

Parish Magazine Ashprington Cornworthy Dittisham May 2021 Away with the Fairies in 1917. My three year old granddaughter Lily loves fairy stories and so, apparently, did Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes. He totally believed in the Cottingley Fairies. In 1917 two talented cousins, Elsie Wright (16) and Frances Griffiths (9), borrowed their father's camera and went down through the bottom of the garden to Cottingley Beck, a stream near Bradford in Yorkshire. There Elsie took five photographs, beautifully composed, showing her cousin Frances watching with a rapt expression a group of fairy folk dancing in front of her. Other photographs showed fairies flying around and a gnome on the grass. The whole process took about half an hour. Such was the skill of the girls' composition that Elsie's mother believed that the little figures really were fairies. Her father, who developed the images, did not believe they were real and considered that the girls had used cardboard cut outs of fairies in the photographs. He refused to lend them his camera again. Elsie's mother Polly was a Theosophist. She went to a meeting in Bradford which happened to be about fairies. She told the president of the Harrogate Theosophists, Edward Gardner, about the photographs and he examined them. Having pronounced them genuine he later contacted Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, a well known Spiritualist, who was writing a piece on fairies for the 1920 Christmas edition of the Strand Magazine. Doyle was totally convinced that the images were real and asked permission to use them in his article. -

4 Brooking Barn Ashprington, Totnes, Devon TQ9 7UL

57 Fore Street, Totnes, Devon TQ9 5NL. Tel: 01803 863888 Email: [email protected] REF: DRO1267 4 Brooking Barn Ashprington, Totnes, Devon TQ9 7UL A MOST ATTRACTIVE DOUBLE FRONTED VILLAGE RESIDENCE, FORMERLY AN OPEN STONE PILLARED BARN CONVERTED TO PROVIDE A SPACIOUS ACCOMMODATION BRIEFLY COMPRISING:- ENTRANCE HALL, LOUNGE, KITCHEN/DINING ROOM, THREE BEDROOMS, EN-SUITE & FAMILY BATHROOM. WITH GARAGE & GARDEN. * * * Offers in the Region of £265,000 * * * www.rendells.co.uk 4 Brooking Barn, Ashprington SITUATION Situated within the very popular and picturesque village of Ashprington, the property stands with a sizable front garden and garage within a party block. Ashprington is approximately two and a half miles from Totnes and within easy driving of the nearby towns of Dartmouth and Kingsbridge. Totnes has a mainline railway station bringing London with three hours travelling, and a choice of two supermarkets with a compliment of multiple and independent shops. The coastlines of the South Hams are within an easy drive as is Dartmoor National Park. DIRECTIONS From Totnes, drive along Station Road in the direction of the station. Proceeding past the station, turn left at the traffic lights on to the Kingsbridge and Dartmouth road. Proceed up the hill through the next set of traffic lights (ignoring the next two turnings on the left) and just beyond the small lodge house on the left there is a turning on the left signposted ‘Ashprington’. Take this turning and drive until you enter the village. Proceeding down the hill into the village, bear right of the monument in front of you. A little way down this lane on the left hand side is No.4 Brooking Barn. -

Environment Agency South West Region

ENVIRONMENT AGENCY SOUTH WEST REGION 1997 ANNUAL HYDROMETRIC REPORT Environment Agency Manley House, Kestrel Way Sowton Industrial Estate Exeter EX2 7LQ Tel 01392 444000 Fax 01392 444238 GTN 7-24-X 1000 Foreword The 1997 Hydrometric Report is the third document of its kind to be produced since the formation of the Environment Agency (South West Region) from the National Rivers Authority, Her Majesty Inspectorate of Pollution and Waste Regulation Authorities. The document is the fourth in a series of reports produced on an annua! basis when all available data for the year has been archived. The principal purpose of the report is to increase the awareness of the hydrometry within the South West Region through listing the current and historic hydrometric networks, key hydrometric staff contacts, what data is available and the reporting options available to users. If you have any comments regarding the content or format of this report then please direct these to the Regional Hydrometric Section at Exeter. A questionnaire is attached to collate your views on the annual hydrometric report. Your time in filling in the questionnaire is appreciated. ENVIRONMENT AGENCY Contents Page number 1.1 Introduction.............................. .................................................... ........-................1 1.2 Hydrometric staff contacts.................................................................................. 2 1.3 South West Region hydrometric network overview......................................3 2.1 Hydrological summary: overview -

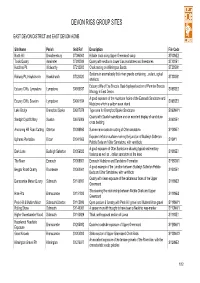

Devon Rigs Group Sites Table

DEVON RIGS GROUP SITES EAST DEVON DISTRICT and EAST DEVON AONB Site Name Parish Grid Ref Description File Code North Hill Broadhembury ST096063 Hillside track along Upper Greensand scarp ST00NE2 Tolcis Quarry Axminster ST280009 Quarry with section in Lower Lias mudstones and limestones ST20SE1 Hutchins Pit Widworthy ST212003 Chalk resting on Wilmington Sands ST20SW1 Sections in anomalously thick river gravels containing eolian ogical Railway Pit, Hawkchurch Hawkchurch ST326020 ST30SW1 artefacts Estuary cliffs of Exe Breccia. Best displayed section of Permian Breccia Estuary Cliffs, Lympstone Lympstone SX988837 SX98SE2 lithology in East Devon. A good exposure of the mudstone facies of the Exmouth Sandstone and Estuary Cliffs, Sowden Lympstone SX991834 SX98SE3 Mudstone which is seldom seen inland Lake Bridge Brampford Speke SX927978 Type area for Brampford Speke Sandstone SX99NW1 Quarry with Dawlish sandstone and an excellent display of sand dune Sandpit Clyst St.Mary Sowton SX975909 SX99SE1 cross bedding Anchoring Hill Road Cutting Otterton SY088860 Sunken-lane roadside cutting of Otter sandstone. SY08NE1 Exposed deflation surface marking the junction of Budleigh Salterton Uphams Plantation Bicton SY041866 SY0W1 Pebble Beds and Otter Sandstone, with ventifacts A good exposure of Otter Sandstone showing typical sedimentary Dark Lane Budleigh Salterton SY056823 SY08SE1 features as well as eolian sandstone at the base The Maer Exmouth SY008801 Exmouth Mudstone and Sandstone Formation SY08SW1 A good example of the junction between Budleigh -

Views to John Fenton Using the Cake Stall in the Lifeboat Station

Editor JOHN FENTON Masthead Design NICHOLAS SHILABEER Printing KINGFISHER May 2012 Issue 14 Production JEFF COOPER been to incidents there. But how many do you think were in the river North of the Higher Ferry or to incidents out in Start Bay? Question 1. North of the Higher Ferry A: 15-20%. B: 20-25%. C: 25-30%. or D: 30-35%. Start Bay A: 15-20%. B: 20-25%. C: 25-30%. or The Spirit of the Dart out on a shout Photo by Andy Kyle Photo by D: 30-35%. Of the ninety nine vessels we have launched to assist 52% have been What have we done? motorboats, but sail craft are not far After four and a half years we have the fundraising side that it is difficult to see behind at 37%. The latter have required enough records to look back and see how we could all keep up without it and assistance for a variety of reasons. Crab how reality is different from our initial the weekly summary that follows. pot lines round the prop have entangled expectations. I for one imagined that after An observation from Dartmouth Coast three. Capsizes accounted for another the initial rush of enthusiasm the need for Guard Station Officer Andy Pound who pair. Two more sprang leaks and a third training and commitment to it would fall said that “in the two years before there ran aground. One single handed sailor away. In fact the time on the water has was a lifeboat on the Dart the land based had simply fallen asleep and was drifting remained remarkably constant. -

Ashprington Cornworthy Dittisham February 2021 HOPE

Parish Magazine Ashprington Cornworthy Dittisham February 2021 HOPE When the storm has passed and the roads are tamed We’ll understand how fragile and we are the survivors it is to be alive. of a collective shipwreck. We’ll sweat empathy for those still with us and those who are gone. With a tearful heart and our destiny blessed We’ll miss the old man we will feel joy who asked for a buck in the market simply for being alive. whose name we never knew who was always at your side. And we’ll give a hug to the first stranger And maybe the poor old man and praise our good luck was your God in disguise that we kept a friend. But you never asked his name because you never had the time. And then we’ll remember all that we lost And all will become a miracle. and finally learn And all will become a legacy. everything we never learned. And we’ll respect the life, the life we have gained. And we’ll envy no one for all of us have suffered When the storm passes and we’ll not be idle I ask you Lord, in shame but be more compassionate. that you return us better, as you once dreamed us. We’ll value more what belongs to all than what was earned. We’ll be more generous “Esperanza” and much more committed. Alexis Valdes, Miami, 2020 About the Magazine HOPE If you would like to receive the Parish Magazine please contact the distribution organiser for your village: Ashprington: Mr. -

TOTNES MISSION COMMUNITY the Benefice of Totnes With

TOTNES MISSION COMMUNITY Appointment of Team Rector January 2020 AN INTRODUCTION TO he Benefice of Totnes with T Bridgetown, Ashprington, Berry Pomeroy Brooking, Cornworthy Dartington, Marldon and Stoke Gabriel. A note from the Archdeacon Every place is special in its own way, but the ancient market town of Totnes and the beautiful South Hams of Devon in which it is set are exceptional. Both the town itself, with its distinguished history and considerable present interest, and the rural communities surrounding it offer an unusually rich and varied cultural life, from the firmly traditional to the decidedly unconventional. Totnes has long been a centre for those seeking forms of spirituality and lifestyle alternative to the mainstream, at the same time retaining all the inherited elements of a fine old West Country market town. With Dartington Hall, Schumacher College, the Sharpham Estate, and other local organisations operating in the area of the benefice, the range of cultural and educational opportunities on offer locally is high, drawing people to Totnes from across the country and beyond. The villages are home to a mix of incomers and those with local roots. There are areas of great wealth within the benefice, and also areas of severe poverty and social deprivation. In all this, the churches of the benefice demonstrate a clear and increasing engagement with their vocation to grow in prayer, make disciples, and serve the people of their communities with joy. The person called to be the next Team Rector will need to demonstrate the capacity to exercise strong, clear, loving leadership in mission and service, working with a gifted and motivated team of colleagues to develop and implement the impressive action plan to which the churches are committed. -

Dart Estuary, Devon

EC Regulation 854/2004 CLASSIFICATION OF BIVALVE MOLLUSC PRODUCTION AREAS IN ENGLAND AND WALES SANITARY SURVEY REPORT Dart Estuary (Devon) 2010 SANITARY SURVEY REPORT DART ESTUARY Cover photo: Pacific oysters in bags at Flat Owers (Dart Estuary). CONTACTS: For enquires relating to this report or further For enquires relating to policy matters on information on the implementation of the implementation of sanitary surveys in sanitary surveys in England and Wales: England and Wales: Simon Kershaw/Carlos Campos Linden Jack Food Safety Group Hygiene & Microbiology Division Shellfish Hygiene (Statutory) Team Food Standards Agency Cefas Weymouth Laboratory Aviation House Barrack Road, The Nothe 125 Kingsway Weymouth London Dorset WC2B 6NH DT43 8UB ( +44 (0) 1305 206600 ( +44 (0) 20 7276 8955 * [email protected] * [email protected] © Crown copyright, 2010 Overall Review of Production Areas 2 SANITARY SURVEY REPORT DART ESTUARY STATEMENT OF USE: This report provides information from a study of the information available relevant to perform a sanitary survey of bivalve mollusc production areas in the Dart Estuary. Its primary purpose is to demonstrate compliance with the requirements for classification of bivalve mollusc production areas, laid down in EC Regulation 854/2004 laying down specific rules for the organisation of official controls on products of animal origin intended for human consumption. The Centre for Environment, Fisheries & Aquaculture Science (Cefas) undertook this work on behalf of the Food Standards Agency (FSA). DISSEMINATION: Food Standards Agency, South Hams District Council (Environmental Health), Devon Sea Fisheries Committee, Environment Agency. RECOMMENDED BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE: Cefas, 2010. Sanitary survey of the Dart Estuary (Devon). -

Twentieth Century War Memorials in Devon

386 The Materiality of Remembrance: Twentieth Century War Memorials in Devon Volume Two of Two Samuel Walls Submitted by Samuel Hedley Walls, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Research in Archaeology, April 2010. This dissertation is available for library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signed.................................................................. Samuel Walls 387 APPENDIX 1: POPULATION FIGURES IN STUDY AREAS These tables are based upon figures compiled by Great Britain Historical GIS Project (2009), Hoskins (1964), Devon Library and Information Services (2005). EAST DEVON Parish Coastline Train Notes on Boundary Changes 1891 1901 1911 1921 1931 1951 Station Awliscombe 497 464 419 413 424 441 Axminster 1860 – 2809 2933 3009 2868 3320 4163 Present Axmouth Yes Part of the parish transferred in 1939 to the newly combined 615 643 595 594 641 476 Combpyne Rousdon Parish. Aylesbeare The dramatic drop in population is because in 1898 the Newton 786 225 296 310 307 369 Poppleford Parish was created out of the parish. Beer Yes 1046 1118 1125 1257 1266 1389 Beer was until 1894 part of Seaton. Branscombe Yes 742 627 606 588 538 670 Broadclyst 1860 – 2003 1900 1904 1859 1904 2057 1966 Broadhembury 601 554 611 480 586 608 Buckerell 243 240 214 207 224 218 Chardstock This parish was transferred to Devon from Dorset in 1896. -

Local Attractions – South Devon

Local Attractions – South Devon Finlake Horse Riding Centre Finlake Resort, Chudleigh Hacking through 130 acres of private parkland and rolling countryside. Lessons from beginners right the way up to advanced. 01626 852096 (please book in advance) [email protected] http://www.finlakeridingcentre.com/ Address: 1 Stokelake Farm Cottages, Chudleigh, Newton Abbot, Devon, TQ13 0EH The Rock Climbing Centre Finlake Resort, Chudleigh Moving from tree to tree on zip slides, bridges, airy platforms. Wall climbing and bouldering also available. Suitable for all ages, no previous experience needed. 01626 852717 (please book in advance) 07974852392 [email protected] http://www.users.globalnet.co.uk/~trc/onsite.htm Address: The Rock Centre, Chudleigh, South Devon, TQ13 0EJ Becky Falls Woodland Park Manaton, 4 miles from Bovey Tracey Voted Devon’s top beauty spot and chosen as one of the WWF’s amazing family days out. Woodland park with features such as a children’s zoo, woodland trail and crafts. 01647 221259 07974852392 https://www.beckyfalls.com Address: Manaton, Newton Abbot Devon, TQ13 9UG Attractions local to Lodge Nine Page 1 Local Attractions – South Devon Babbacombe Model Village Torguay Thousands of miniature buildings, people and vehicles, along with animated scenes and touches of English humour, capture the essence of England’s past, present and future. 01803 315315 [email protected] http://www.model-village.co.uk/ Address: Hampton Avenue, Babbacombe Torquay, Devon, TQ1 3LA House of Marbles/ Teign Valley Glass/The Orangery Restaurant Bovey Tracey It is a working glass, toys and games factory set in a historic pottery. Discover traditional and modern glass making technics at work, visit museums of games, glass, pottery and marbles. -

List -275-Inprint

T H E C O L O P H O N B O O K S H O P Robert and Christine Liska P. O. B O X 1 0 5 2 E X E T E R N E W H A M P S H I R E 0 3 8 3 3 ( 6 0 3 ) 7 7 2 8 4 4 3 List 275 Books about Books * Recent Publications All items listed have been carefully described and are in fine collector’s condition unless otherwise noted. All are sold on an approval basis and any purchase may be returned within two weeks for any reason. Member ABAA and ILAB. All items are offered subject to prior sale. Please add $5.00 shipping for the first book, $1.00 for each additional volume. New clients are requested to send remittance with order. All shipments outside the United States will be charged shipping at cost. We accept VISA, MASTERCARD and AMERICAN EXPRESS. (603) 772-8443; FAX (603) 772-3384; e-mail: [email protected] Please visit our web site to view MANY additional images and titles. http://www.colophonbooks.com ☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼ 1. (ALDINE PRESS). MILLS, Adam. Aldines At Harrow : A Discursive Catalogue. The Aldine Press Collection of Lionel Oliver Bigg at Harrow School, The Old Speech Room Gallery. Cambridge: Adam Mills Rare Books, 2020, folio, blue boards lettered in white, Aldine device in gold. vi, 256 pp. First Edition. Comprises a short Introduction to Aldine collectors & collections; and 167 discursive entries detailing the Aldine Collection bequeathed by Lionel Oliver Bigg to Harrow School in 1887; also a separate section on the Aldine Cicero Editions. -

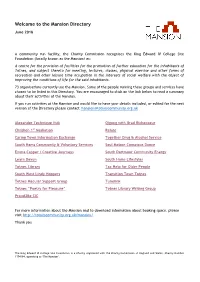

The Mansion Directory

Welcome to the Mansion Directory June 2018 A community run facility, the Charity Commission recognises the King Edward IV College Site Foundation (locally known as the Mansion) as: A centre for the provision of facilities for the promotion of further education for the inhabitants of Totnes, and subject thereto for meeting, lectures, classes, physical exercise and other forms of recreation and other leisure time occupation in the interests of social welfare with the object of improving the conditions of life for the said inhabitants. 73 organisations currently use the Mansion. Some of the people running these groups and services have chosen to be listed in this Directory. You are encouraged to click on the link below to read a summary about their activities at the Mansion. If you run activities at the Mansion and would like to have your details included, or edited for the next version of the Directory please contact [email protected] Alexander Technique Hub Qigong with Brad Richecoeur Children 1st Mediation Relate Caring Town Information Exchange Together Drug & Alcohol Service South Hams Community & Voluntary Services Soul Motion Conscious Dance Emma Capper / Creative Journeys South Dartmoor Community Energy Learn Devon South Hams Lifestyles Totnes Library Tax Help for Older People South West Lindy Hoppers Transition Town Totnes Totnes Macular Support Group Tunelink Totnes “Poetry for Pleasure” Totnes Library Writing Group Proud2Be CIC For more information about the Mansion and to download information about booking space, please visit http://totnescommunity.org.uk/mansion/ Thank you The King Edward VI College Site Foundation is a Charity registered with the Charity Commission of England and Wales.