Plaintiffs' Opening Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Order 13224

1358 Sept. 22 / Administration of George W. Bush, 2001 22. The transcript was made available by the Of- 9001(a) of the Department of Defense Ap- fice of the Press Secretary on September 21 but propriations Act, 2000 (Public Law 106–79), was embargoed for release until the broadcast. I hereby waive, with respect to India and The Office of the Press Secretary also released Pakistan, to the extent not already waived, a Spanish language transcript of this address. the application of any sanction contained in section 101 or 102 of the Arms Export Con- Statement on Signing the Air trol Act, section 2(b)(4) of the Export Import Transportation Safety and System Bank Act of 1945, and section 620E(e) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as Stabilization Act amended. September 22, 2001 You are authorized and directed to trans- mit this determination and certification to Today I signed the Airline Transportation the appropriate committees of the Congress and Systems Stabilization Act, which will pro- and to arrange for its publication in the Fed- vide urgently needed tools to assure the safe- eral Register. ty and immediate stability of our Nation’s commercial airline system. This important George W. Bush legislation also establishes a process for com- [Filed with the Office of the Federal Register, pensating victims of the terrorist attacks. 8:45 a.m., October 1, 2001] The terrorists who attacked our country on September 11th will not shut down our vital NOTE: This memorandum will be published in the businesses or thwart our way of life. -

Terrorist Assets Report 2018

TERRORIST ASSETS REPORT Calendar Year 2018 Twenty-seventh Annual Report to the Congress on Assets in the United States Relating to Terrorist Countries and Organizations Engaged in International Terrorism Office of Foreign Assets Control U.S. Department of the Treasury TERRORIST ASSETS REPORT Calendar Year 2018 Twenty-seventh Annual Report to the Congress on Assets in the United States Relating to Terrorist Countries and Organizations Engaged in International Terrorism OFFICE OF FOREIGN ASSETS CONTROL U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY CONTENTS Background A. Economic Sanctions and Terrorism B. Nature of Blocked Assets C. Nature of OFAC Information Sources D. This Report Part I: Assets Relating to International Terrorist Organizations A. Programs B. Administering and Enforcing Terrorism Sanctions C. Impact of Terrorism Sanctions D. Summary of Blocked Assets Relating to International Terrorist Organizations E. Real and Tangible Property Relating to International Terrorist Organizations Exhibit A Blocked Funds in the United States Relating to the SDGT, SDT, and FTO Programs Part II: Assets Relating to State Sponsors of Terrorism A. State Sponsors of Terrorism B. Reported Blocked Assets Relating to State Sponsors of Terrorism C. Real and Tangible Property of State Sponsors of Terrorism Table 1 Blocked Funds in the United States Relating to State Sponsors of Terrorism Attachments Tab 1 Statutory Reporting Requirement on Terrorist Assets in United States Tab 2 Federal Agencies Polled for Information References This report cites a number of sanctions-related authorities including executive orders. All of the legal materials cited in this report may be found in the legal section of OFAC’s website at the following URL: https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/Pages/legal-index.aspx 1 BACKGROUND A. -

Homeland Security Related Executive Orders (E.O

111TH CONGRESS COMMITTEE " COMMITTEE PRINT ! 2nd Session PRINT 111–A COMPILATION OF HOMELAND SECURITY RELATED EXECUTIVE ORDERS (E.O. 4601 Through E.O. 13528) (1927-2009) PREPARED FOR THE USE OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES June 2010 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 56–961 PDF WASHINGTON : 2010 Compilation of Homeland Security Related Executive Orders (E.O. 4601 Through E.O. 13528) 111TH CONGRESS COMMITTEE " COMMITTEE PRINT ! 2nd Session PRINT 111–A COMPILATION OF HOMELAND SECURITY RELATED EXECUTIVE ORDERS (E.O. 4601 Through E.O. 13528) (1927-2009) PREPARED FOR THE USE OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES June 2010 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 56–961 PDF WASHINGTON : 2010 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi, Chairman LORETTA SANCHEZ, California PETER T. KING, New York JANE HARMAN, California LAMAR SMITH, Texas PETER A. DEFAZIO, Oregon DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of MIKE ROGERS, Alabama Columbia MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas ZOE LOFGREN, California CHARLES W. DENT, Pennsylvania SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas GUS M. BILIRAKIS, Florida HENRY CUELLAR, Texas PAUL C. BROUN, Georgia CHRISTOPHER P. CARNEY, Pennsylvania CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan YVETTE D. CLARKE, New York PETE OLSON, Texas LAURA RICHARDSON, California ANH ‘‘JOSEPH’’ CAO, Louisiana ANN KIRKPATRICK, Arizona STEVE AUSTRIA, Ohio BILL PASCRELL, JR., New Jersey VACANCY EMANUEL CLEAVER, Missouri AL GREEN, Texas JAMES A. HIMES, Connecticut MARY JO KILROY, Ohio DINA TITUS, Nevada WILLIAM L. OWENS, New York VACANCY VACANCY I. Lanier Avant, Staff Director & General Counsel Rosaline Cohen, Chief Counsel Michael S. Twinchek, Chief Clerk Robert O’Connor, Minority Staff Director ——————— Prepared by Michael S. -

Sanctions and Export Control Developments in the First 50 Days of the Biden Administration

Sanctions and Export Control Developments in the First 50 Days of the Biden Administration By Elizabeth G. Silver, John E. Bradley and Aleksandra Rybicki March 17, 2021 Monitoring sanctions developments as a heat map for U.S. foreign policy and national security under the Biden Administration. As the calendar flipped past the 50th day of President Joe Biden’s administration on March 11, 2021, a survey of economic sanctions and export control-related developments shows where the Administration felt a pressing need to impose new sanctions, alter existing policies or, in several areas, clarify existing programs. To date, we have not seen substantial changes to any ongoing sanctions programs by the Biden Administration, but we will be watching complex hot spots such as China and Iran as the Administration works through the nuances of its foreign policy and deepens its diplomatic efforts over the coming weeks and months. In this bulletin, we share our thinking on these early developments with our clients and friends to help you keep your sanctions programs current and monitor shifting risk levels posed by your international operations. Africa Democratic Republic of the Congo and Mozambique The Biden Administration advanced the long-standing sanctions program against foreign terrorist organizations operating on the African continent with the designation by the Department of State of two affiliates of the Islamic State, one each in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Mozambique, as “foreign terrorist organizations,” adding them to the Office of Foreign Assets Control’s (“OFAC”) Specially Designated Nationals (“SDN”) List and subjecting them to broad sanctions. Allied Democratic Forces (also known as ISIS-DRC (“ADF”)) and Ansar al-Sunna (also known as ISIS- Mozambique) are believed to be responsible for multiple attacks on civilians and government security forces that have Vedder Price P.C. -

The President of the United States

1 115th Congress, 2d Session – – – – – – – – – – – – House Document 115–154 CONTINUATION OF THE NATIONAL EMERGENCY WITH RESPECT TO PERSONS WHO COMMIT, THREATEN TO COMMIT, OR SUPPORT TERRORISM COMMUNICATION FROM THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING A NOTIFICATION THAT THE NATIONAL EMERGENCY DECLARED WITH RESPECT TO PERSONS WHO COMMIT, THREATEN TO COM- MIT, OR SUPPORT TERRORISM, DECLARED IN EXECUTIVE ORDER 13224 OF SEPTEMBER 23, 2001, IS TO CONTINUE IN EF- FECT BEYOND SEPTEMBER 23, 2018, PURSUANT TO 50 U.S.C. 1622(d); PUBLIC LAW 94–412, SEC. 202(d); (90 STAT. 1257) SEPTEMBER 20, 2018.—Referred to the Committee on Foreign Affairs and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 79–011 WASHINGTON : 2018 VerDate Sep 11 2014 04:30 Sep 21, 2018 Jkt 079011 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HD154.XXX HD154 E:\Seals\Congress.#13 VerDate Sep 11 2014 04:30 Sep 21, 2018 Jkt 079011 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HD154.XXX HD154 THE WHITE HOUSE, Washington, September 19, 2018. Hon. PAUL D. RYAN, Speaker of the House of Representatives, Washington, DC. DEAR MR. SPEAKER: Section 202 (d) of the National Emergencies Act (50 U.S.C. 1622(d)) provides for the automatic termination of a national emergency unless, within 90 days before the anniversary date of its declaration, the President publishes in the Federal Reg- ister and transmits to the Congress a notice stating that the emer- gency is to continue in effect beyond the anniversary date. In ac- cordance with this provision, I have sent to the Federal Register for publication the enclosed notice stating that the national emergency with respect to persons who commit, threaten to commit, or sup- port terrorism declared in Executive Order 13224 of September 23, 2001, is to continue in effect beyond September 23, 2018. -

Holy Land Foundation for Relief and Development: Criminalizing Support for Non-Designated Charities

Blocking Faith, Freezing Charity CHILLING MUSLIM CHARITABLE GIVING in the “WAR ON TERRORISM FINANCING” Blocking Faith, Freezing Charity: Chilling Muslim Charitable Giving in the “War on Terrorism Financing” PUBLISHED: June 2009 FRONT COVER PHOTOGRAPH: Alex Wong/Getty Images Members of a Muslim congregation in Virginia give Zakat donations for the needy before they enter a mosque for a service to mark the conclusion of the holy month of Ramadan, the height of annual Muslim charitable giving. Zakat is one of the core “five pillars” of Islam and a religious obligation for all observant Muslims. BACK COVER PHOTOGRAPHS: LEFT: Brandon Dill/Memphis Commercial Appeal RIGHT: LIFE for Relief and Development THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION is the nation’s premier guardian of liberty, working daily in courts, legislatures and communities to defend and preserve the individual rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution, the laws and treaties of the United States. OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS Susan N. Herman, President Anthony D. Romero, Executive Director Richard Zacks, Treasurer ACLU NATIONAL OFFICE 125 Broad Street, 18th Fl. New York, NY 10004-2400 (212) 549-2500 www.aclu.org Contents I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND INTRODUCTION ................................................................................ 7 a. Introduction .............................................................................................................................7 b. Executive Summary .................................................................................................................9 -

Iran Sanctions Relief

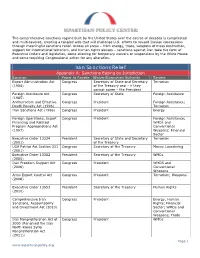

The comprehensive sanctions regime built by the United States over the course of decades is complicated and multi-layered, creating a tangled web that will challenge U.S. efforts to reward Iranian concessions through meaningful sanctions relief. Across all areas – from energy, trade, weapons of mass destruction, support for international terrorism, and human rights abuses – sanctions against Iran take the form of Executive Orders and legislation, some allowing for temporary waivers or suspensions by the White House and some requiring Congressional action for any alteration. Iran Sanctions Relief Appendix A: Sanctions Easing by Jurisdiction Sanction Power to Revoke Waiver/Exemption Authority Targets Export Administration Act Congress Secretary of State and Secretary Terrorism (1984) of the Treasury and – if they cannot agree – the President Foreign Assistance Act Congress Secretary of State Foreign Assistance (1985) Antiterrorism and Effective Congress President Foreign Assistance; Death Penalty Act (1996) Terrorism Iran Sanctions Act (1996) Congress President Energy Foreign Operations, Export Congress President Foreign Assistance; Financing and Related WMDs and Program Appropriations Act Conventional (1997) Weapons; Financial Sector Executive Order 13224 President Secretary of State and Secretary Terrorism (2001) of the Treasury USA Patriot Act Section 311 Congress Secretary of the Treasury Money Laundering (2001) Executive Order 13382 President Secretary of the Treasury WMDs (2005) Iran Freedom Support Act Congress President WMDS and -

Open the Document

Presidential Proclamation--Suspension of Entry of Aliens Subject to United Nations Secu... Page 1 of 4 Home • Briefing Room • Presidential Actions • Proclamations The White House Office of the Press Secretary For Immediate Release July 25, 2011 Presidential Proclamation--Suspension of Entry of Aliens Subject to United Nations Security Council Travel Bans and International Emergency Economic Powers Act Sanctions SUSPENSION OF ENTRY OF ALIENS SUBJECT TO UNITED NATIONS SECURITY COUNCIL TRAVEL BANS AND INTERNATIONAL EMERGENCY ECONOMIC POWERS ACT SANCTIONS BY THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA A PROCLAMATION In light of the firm commitment of the United States to the preservation of international peace and security and our obligations under the United Nations Charter to carry out the decisions of the United Nations Security Council imposed under Chapter VII, I have determined that it is in the interests of the United States to suspend the entry into the United States, as immigrants or nonimmigrants, of aliens who are subject to United Nations Security Council travel bans as of the date of this proclamation. I have further determined that the interests of the United States are served by suspending the entry into the United States, as immigrants or nonimmigrants, of aliens whose property and interests in property have been blocked by an Executive Order issued in whole or in part pursuant to the President's authority under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (50 U.S.C. 1701 et seq.). NOW, THEREFORE, I, BARACK OBAMA, by the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, including section 212(f) of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, as amended (8 U.S.C. -

U.S.-China Counterterrorism Cooperation: Issues for U.S. Policy

U.S.-China Counterterrorism Cooperation: Issues for U.S. Policy Shirley A. Kan Specialist in Asian Security Affairs July 15, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33001 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress U.S.-China Counterterrorism Cooperation: Issues for U.S. Policy Summary After the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, the United States faced a challenge in enlisting the full support of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the counterterrorism fight against Al Qaeda. This effort raised short-term policy issues about how to elicit cooperation and how to address PRC concerns about the U.S.-led war (Operation Enduring Freedom). Longer-term issues have concerned whether counterterrorism has strategically transformed bilateral ties and whether China’s support was valuable and not obtained at the expense of other U.S. interests. The extent of U.S.-China counterterrorism cooperation has been limited, but the tone and context of counterterrorism helped to stabilize—even if it did not transform—the closer bilateral relationship pursued by President George Bush in late 2001. China’s military, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), has not fought in the U.S.-led counterterrorism coalition. The Bush Administration designated the PRC-targeted “East Turkistan Islamic Movement” (ETIM) as a terrorist organization in August 2002, reportedly allowed PRC interrogators access to Uighur detainees at Guantanamo in September 2002, and held a summit in Texas in October 2002. Since 2005, however, U.S. concerns about China’s extent of cooperation in counterterrorism have increased. In September 2005, Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick acknowledged that “China and the United States can do more together in the global fight against terrorism” after “a good start,” in his policy speech that called on China to be a “responsible stakeholder” in the world. -

High Alert: the Government's War on the Financing of Terrorism and Its Implication for Donors, Domestic Charitable Organizations, and Global Philanthropy

William & Mary Law Review Volume 45 (2003-2004) Issue 4 Article 3 March 2004 High Alert: The Government's War on the Financing of Terrorism and Its Implication for Donors, Domestic Charitable Organizations, and Global Philanthropy Nina J. Crimm [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the National Security Law Commons Repository Citation Nina J. Crimm, High Alert: The Government's War on the Financing of Terrorism and Its Implication for Donors, Domestic Charitable Organizations, and Global Philanthropy, 45 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 1341 (2004), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol45/iss4/3 Copyright c 2004 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr HIGH ALERT: THE GOVERNMENT'S WAR ON THE FINANCING OF TERRORISM AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR DONORS, DOMESTIC CHARITABLE ORGANIZATIONS, AND GLOBAL PHILANTHROPY NINA J. CRIMM* ABSTRACT Within days after the September 11 terrorist attacks, the U.S. government extended its already existing commitment to combat terrorism. President Bush declared a financial war on terrorism, with the aim of depriving terrorists of their necessary financial support. He issued Executive Order 13,224, which ordered the blocking of assets of specially designated global terrorists.' Congress enacted legislation that not only fortified previously existing criminal and civil laws, but also added new ones for use in combating terrorists and terrorism. The Bush Administration dedicated resources to existing and newly created governmental structures that would be responsible for enforcing these laws and for waging the financial war on terrorism. -

United States Expands Terrorist Financing Sanctions

POLICY ALERT // SEPTEMBER 17, 2019 United States Expands Terrorist Financing Sanctions The President on September 10, 2019, authorized the Treasury Secretary to impose sanctions on non-U.S. financial institutions that have knowingly conducted or facilitated a “significant” transaction with anyone sanctioned by the United States as a specially designated global terrorist (SDGT).1 The new executive order amended Executive Order 13224, which has been the cornerstone of U.S. counter-terrorist financing efforts since 2001.2 The new executive order increases direct and indirect sanctions risk for non-U.S. financial institutions at the same time that the geographic reach of the U.S. counterterrorism sanctions program is expanding. ▶ The new executive order authorizes the Treasury Secretary to prohibit U.S. financial institutions from establishing or maintaining correspondent accounts for non-U.S. financial institutions determined to have “knowingly conducted or facilitated any significant transaction” on behalf of anyone whose property is blocked under Executive Order 13224.3 Alternatively, the Treasury Secretary may impose strict conditions on such relationships.4 ▶ The Treasury Department retains the authority to block the property of non- U.S. financial institutions that have provided services to anyone sanctioned under Executive Order 13224.5 On September 10, 2019, the Treasury Department imposed blocking sanctions on five money transmitters and one jeweler for providing financial services to groups sanctioned under Executive Order 13224.6 ▶ The new executive order gives the U.S. government more flexibility in targeting financial institutions that have knowingly conducted transactions involving terrorists, with a menu of three sanctions options: blocking, prohibiting correspondent accounts, or imposing strict conditions on relationships.7 Having the ability to calibrate sanctions may make targeting larger financial institutions more attractive to Treasury officials. -

Handbook on Counter-Terrorism Measures: What U.S

Day, Berry & Howard FOUNDATION Handbook on Counter-Terrorism Measures: What U.S. Nonprofits and Grantmakers Need to Know A plain-language guide to Executive Order 13224, the Patriot Act, embargoes and sanctions, IRS rules, Treasury Department voluntary guidelines, and USAID requirements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PRELIMINARY NOTE .............................................................................................................iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... v I. BACKGROUND AND OVERVIEW OF COUNTER-TERRORISM RULES ............... 1 II. EXECUTIVE ORDER 13224............................................................................................ 2 Summary............................................................................................................................ 2 Background of Executive Order 13224 ............................................................................. 3 What is the legal status of the Executive Order? ............................................................... 3 What does the Executive Order do?................................................................................... 4 Where to look to identify known or suspected terrorists relevant under the Executive Order. .................................................................................................... 5 What does “terrorism” mean, as used in the Executive Order?......................................... 6 Is knowledge or