Scottish Wildcat Survey Report 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation of the Wildcat (Felis Silvestris) in Scotland: Review of the Conservation Status and Assessment of Conservation Activities

Conservation of the wildcat (Felis silvestris) in Scotland: Review of the conservation status and assessment of conservation activities Urs Breitenmoser, Tabea Lanz and Christine Breitenmoser-Würsten February 2019 Wildcat in Scotland – Review of Conservation Status and Activities 2 Cover photo: Wildcat (Felis silvestris) male meets domestic cat female, © L. Geslin. In spring 2018, the Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan Steering Group commissioned the IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group to review the conservation status of the wildcat in Scotland and the implementation of conservation activities so far. The review was done based on the scientific literature and available reports. The designation of the geographical entities in this report, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The SWCAP Steering Group contact point is Martin Gaywood ([email protected]). Wildcat in Scotland – Review of Conservation Status and Activities 3 List of Content Abbreviations and Acronyms 4 Summary 5 1. Introduction 7 2. History and present status of the wildcat in Scotland – an overview 2.1. History of the wildcat in Great Britain 8 2.2. Present status of the wildcat in Scotland 10 2.3. Threats 13 2.4. Legal status and listing 16 2.5. Characteristics of the Scottish Wildcat 17 2.6. Phylogenetic and taxonomic characteristics 20 3. Recent conservation initiatives and projects 3.1. Conservation planning and initial projects 24 3.2. Scottish Wildcat Action 28 3.3. -

Felis Silvestris, Wild Cat

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2008: T60354712A50652361 Felis silvestris, Wild Cat Assessment by: Yamaguchi, N., Kitchener, A., Driscoll, C. & Nussberger, B. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Yamaguchi, N., Kitchener, A., Driscoll, C. & Nussberger, B. 2015. Felis silvestris. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T60354712A50652361. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T60354712A50652361.en Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; Microsoft; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; Wildscreen; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information -

The Dewars of St. Fillan

History of the Clan Macnab part five: The Dewars of St. Fillan The following articles on the Dewar Sept of the Clan Macnab were taken from several sources. No attempt has been made to consolidate the articles; instead they are presented as in the original source, which is given at the beginning of each section. Hence there will be some duplication of material. David Rorer Dewar means roughly “custodian” and is derived from the Gallic “Deoradh,” a word originally meaning “stranger” or “wanderer,” probably because the person so named carried St. Fillan’s relics far a field for special purposes. Later, the meaning of the word altered to “custodian.” The relics they guarded were the Quigrich (Pastoral staff); the Bernane (chapel Bell), the Fergy (possibly St. Fillan’s portable alter), the Mayne (St. Fillan’s arm bone), the Maser (St. Fillan’s manuscript). There were, of course other Dewars than the Dewars of St. Fillan and the name today is most familiar as that of a blended scotch whisky produced by John Dewar and Sons Ltd St. Fillan is mentioned in the Encyclopedia Britannica, 14th edition of 1926, as follows: Fillan, Saint or Faelan, the name of two Scottish saints, of Irish origin, whose lives are of a legendary character. The St. Fillan whose feast is kept on June 20 had churches dedicated to him at Ballyheyland, Queen’s county, Ireland, and at Loch Earn, Perthshire (see map of Glen Dochart). The other, who is commerated on January 9, was specially venerated at Cluain Mavscua in County Westmeath, Ireland. Also beginning about the 8th or 9th century at Strathfillan, Perthshire, Scotland, where there was an ancient monastery dedicated to him. -

African Wildcat 1 African Wildcat

African Wildcat 1 African Wildcat African Wildcat[1] Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Family: Felidae Genus: Felis Species: F. silvestris Subspecies: F. s. lybica Trinomial name Felis silvestris lybica Forster, 1770 The African wildcat (Felis silvestris lybica), also known as the desert cat, and Vaalboskat (Vaal-forest-cat) in Afrikaans, is a subspecies of the wildcat (F. silvestris). They appear to have diverged from the other subspecies about 131,000 years ago.[2] Some individual F. s. lybica were first domesticated about 10,000 years ago in the Middle East, and are among the ancestors of the domestic cat. Remains of domesticated cats have been included in human burials as far back as 9,500 years ago in Cyprus.[3] [4] Physical characteristics The African wildcat is sandy brown to yellow-grey in color, with black stripes on the tail. The fur is shorter than that of the European subspecies. It is also considerably smaller: the head-body length is 45 to 75 cm (17.7 to 29.5 inches), the tail 20 to 38 cm (7.87 to 15 inches), and the weight ranges from 3 to 6.5 kg (6.61 to 14.3 lbs). Distribution and habitat The African wildcat is found in Africa and in the Middle East, in a wide range of habitats: steppes, savannas and bushland. The sand cat (Felis margarita) is the species found in even more arid areas. Skull African Wildcat 2 Behaviour The African wildcat eats primarily mice, rats and other small mammals. When the opportunity arises, it also eats birds, reptiles, amphibians, and insects. -

The River Tay - Its Silvery Waters Forever Linked to the Picts and Scots of Clan Macnaughton

THE RIVER TAY - ITS SILVERY WATERS FOREVER LINKED TO THE PICTS AND SCOTS OF CLAN MACNAUGHTON By James Macnaughton On a fine spring day back in the 1980’s three figures trudged steadily up the long climb from Glen Lochy towards their goal, the majestic peak of Ben Lui (3,708 ft.) The final arête, still deep in snow, became much more interesting as it narrowed with an overhanging cornice. Far below to the West could be seen the former Clan Macnaughton lands of Glen Fyne and Glen Shira and the two big Lochs - Fyne and Awe, the sites of Fraoch Eilean and Dunderave Castle. Pointing this out, James the father commented to his teenage sons Patrick and James, that maybe as they got older the history of the Clan would interest them as much as it did him. He told them that the land to the West was called Dalriada in ancient times, the Kingdom settled by the Scots from Ireland around 500AD, and that stretching to the East, beyond the impressively precipitous Eastern corrie of Ben Lui, was Breadalbane - or upland of Alba - part of the home of the Picts, four of whose Kings had been called Nechtan, and thus were our ancestors as Sons of Nechtan (Macnaughton). Although admiring the spectacular views, the lads were much more keen to reach the summit cairn and to stop for a sandwich and some hot coffee. Keeping his thoughts to himself to avoid boring the youngsters, and smiling as they yelled “Fraoch Eilean”! while hurtling down the scree slopes (at least they remembered something of the Clan history!), Macnaughton senior gazed down to the source of the mighty River Tay, Scotland’s biggest river, and, as he descended the mountain at a more measured pace than his sons, his thoughts turned to a consideration of the massive influence this ancient river must have had on all those who travelled along it or lived beside it over the millennia. -

Serval Fact Sheet

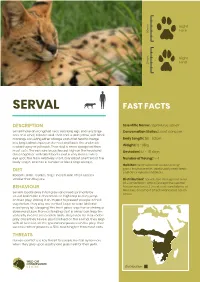

Right 50mm Fore Right 50mm Hind SERVAL FAST FACTS DESCRIPTION Scientific Name: Leptailurus serval Servals have an elongated neck, very long legs, and very large Conversation Status: Least concern ears on a small, delicate skull. Their coat is pale yellow, with black markings consisting either of large spots that tend to merge Body Length: 59 - 92cm into longitudinal stripes on the neck and back. The underside is whitish grey or yellowish. Their skull is more elongated than Weight: 12 - 18kg most cats. The ears are broad based, high on the head and Gestation: 67 - 79 days close together, with black backs and a very distinct white eye spot. The tail is relatively short, only about one third of the Number of Young: 1 - 4 body length, and has a number of black rings along it. Habitat: Well-watered savanna long- grass environments, particularly reed beds DIET and other riparian habitats. Rodents, birds, reptiles, frogs, insects and other species smaller than they are. Distribution: Servals live throughout most of sub-Saharan Africa (except the central BEHAVIOUR African rainforest), the deserts and plains of Namibia, and most of Botswana and South Servals locate prey in tall grass and reeds primarily by Africa. sound and make a characteristic high leap as they jump on their prey, striking it on impact to prevent escape in thick vegetation. They also use vertical leaps to seize bird and insect prey by “clapping” the front paws together or striking a downward blow. From a standing start a serval can leap 3m vertically into the air to catch birds. -

Pallas's Cat Status Review & Conservation Strategy

ISSN 1027-2992 I Special Issue I N° 13 | Spring 2019 Pallas'sCAT cat Status Reviewnews & Conservation Strategy 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser a component of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the Co-chairs IUCN/SSC International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is pub- Cat Specialist Group lished twice a year, and is available to members and the Friends of KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, the Cat Group. Switzerland Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] <[email protected]> <[email protected]> Original contributions and short notes about wild cats are welcome Send contributions and observations to Associate Editors: Tabea Lanz [email protected]. Guidelines for authors are available at www.catsg.org/catnews This Special Issue of CATnews has been produced with Cover Photo: Camera trap picture of manul in the support from the Taiwan Council of Agriculture's Forestry Bureau, Kotbas Hills, Kazakhstan, 20. July 2016 Fondation Segré, AZA Felid TAG and Zoo Leipzig. (Photo A. Barashkova, I Smelansky, Sibecocenter) Design: barbara surber, werk’sdesign gmbh Layout: Tabea Lanz and Christine Breitenmoser Print: Stämpfli AG, Bern, Switzerland ISSN 1027-2992 © IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group The designation of the geographical entities in this publication, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Savannah Cat’ ‘Savannah the Including Serval Hybrids Felis Catus (Domestic Cat), (Serval) and (Serval) Hybrids Of

Invasive animal risk assessment Biosecurity Queensland Agriculture Fisheries and Department of Serval hybrids Hybrids of Leptailurus serval (serval) and Felis catus (domestic cat), including the ‘savannah cat’ Anna Markula, Martin Hannan-Jones and Steve Csurhes First published 2009 Updated 2016 © State of Queensland, 2016. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/3.0/au/deed.en" http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Front cover: Close-up of a 4-month old F1 Savannah cat. Note the occelli on the back of the relaxed ears, and the tear-stain markings which run down the side of the nose. Photo: Jason Douglas. Image from Wikimedia Commons under a Public Domain Licence. Invasive animal risk assessment: Savannah cat Felis catus (hybrid of Leptailurus serval) 2 Contents Introduction 4 Identity of taxa under review 5 Identification of hybrids 8 Description 10 Biology 11 Life history 11 Savannah cat breed history 11 Behaviour 12 Diet 12 Predators and diseases 12 Legal status of serval hybrids including savannah cats (overseas) 13 Legal status of serval hybrids including savannah cats -

Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat

UPTEC X 12 012 Examensarbete 30 hp Juni 2012 Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat Carolin Johansson Molecular Biotechnology Programme Uppsala University School of Engineering UPTEC X 12 012 Date of issue 2012-06 Author Carolin Johansson Title (English) Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat Title (Swedish) Abstract This study presents mitochondrial genome sequences from 22 Egyptian house cats with the aim of resolving the uncertain origin of the contemporary world-wide population of Domestic cats. Together with data from earlier studies it has been possible to confirm some of the previously suggested haplotype identifications and phylogeny of the Domestic cat lineage. Moreover, by applying a molecular clock, it is proposed that the Domestic cat lineage has experienced several expansions representing domestication and/or breeding in pre-historical and historical times, seemingly in concordance with theories of a domestication origin in the Neolithic Middle East and in Pharaonic Egypt. In addition, the present study also demonstrates the possibility of retrieving long polynucleotide sequences from hair shafts and a time-efficient way to amplify a complete feline mitochondrial genome. Keywords Feline domestication, cat in ancient Egypt, mitochondrial genome, Felis silvestris libyca Supervisors Anders Götherström Uppsala University Scientific reviewer Jan Storå Stockholm University Project name Sponsors Language Security English Classification ISSN 1401-2138 Supplementary bibliographical information Pages 123 Biology Education Centre Biomedical Center Husargatan 3 Uppsala Box 592 S-75124 Uppsala Tel +46 (0)18 4710000 Fax +46 (0)18 471 4687 Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat Carolin Johansson Populärvetenskaplig sammanfattning Det är inte sedan tidigare känt exakt hur, när och var tamkatten domesticerades. -

Feasibility Study

for Balquhidder, Lochearnhead and Strathyre Community Trust April 2020 Broch Field Feasibility Study Strathyre, Stirlingshire Broch Field Feasibility Study determined that the improvements to the landscape of the site, which can only be achieved through community ownership, would create an attractive Strathyre, Stirlingshire for BLS Community Trust and vibrant space which would balance with the additional burden of care required. These improvements would also have the potential to introduce additional use and income streams into the community. Summary The undertaking of a feasibility study to investigate potential for community ownership of the Broch Field, Strathyre, was awarded to Munro Landscape by the Balquhidder, Lochearnhead and Strathyre (BLS) Community Trust. Community surveys, undertaken by BLS, confirmed a strong desire to take ownership of the field, which is utilised as a ‘village green’ for the local area and hosts regular community events. Key themes emanating from the survey results were taken forward to this study for assessment for viability. A concept proposals plans was produced to explore the potential for a reimagining of the current use of the field and enhancement of existing features. This was developed alongside investigations into the viability of each aspirational project and detailed costings breakdown. Overall conclusions from this study are that the Broch field is a much- needed community asset, with regular use and potential for sensitive, low- key community development. Expansion of the current facilities would support both local the community and visitors to the village and area. Implementation of landscaping improvements can be undertaken in conjunction with the introduction of facilities for the provision of a motorhome stopover, which would assist in supporting the ongoing costs of managing the site. -

Strathyre and Loch Earn

STRATHYRE AND LOCH EARN SPECIAL QUALITIES OF BREADALBANE STRATHYRE & LOCH EARN Key Features Small flats strips of farmland around watercourses Open upland hills Ben Vorlich and Stuc a’Chroin Loch Lubnaig and Loch Earn Pass of Leny Glen Ogle Landmark historic buildings and heritage sites including Edinample Castle and Dundurn Pictish Hill Fort Summary of Evaluation Sense of Place The visual/sense of place qualities are important. The open upland hills dominate much of this area, with Ben Vorlich and Stuc a’ Chroin the highest peaks, creating an open and vast sense of place with diverse features such as rocky outcrops and scree. Although open uplands are characteristic of much of the highland area of the Park they are distinctive in the Breadalbane area as being generally higher and more unbroken with distinct exposed upper slopes. Loch Earn and Loch Lubnaig are the two main lochs in the area and both have quite distinct characters. Loch Lubnaig is enclosed by heavily planted glen sides and rugged craggy hills such as Ben Ledi and the loch shores are largely undeveloped. Loch Earn in contrast is broad in expanse and flanked by steep hills to the north and south. There are areas of residential, recreational and commercial development along areas of the north and south shore. The flat glen floors are a focus for communication routes and settlement. The flat strips of farmland around the watercourses provide an enclosed landscape which contrasts with the surrounding hills. Cultural Heritage The cultural heritage of the area is of high importance with substantial evidence of continuity of use of the landscape. -

Revealed Via Genomic Assessment of Felid Cansines

Evolutionary and Functional Impacts of Short Interspersed Nuclear Elements (SINEs) Revealed via Genomic Assessment of Felid CanSINEs By Kathryn B. Walters-Conte B. S., May 2000, University of Maryland, College Park M. S., May 2002, The George Washington University A Dissertation Submitted to The Faculty of Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 15 th , 2011 Dissertation Directed By Diana L.E. Johnson Associate Professor of Biology Jill Pecon-Slattery Staff Scientist, National Cancer Institute . The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Kathryn Walters-Conte has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of March 24 th , 2011. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Evolutionary and Functional Impacts of Short Interspersed Nuclear Elements (SINEs) Revealed via Genomic Assessment of Felid CanSINEs Kathryn Walters-Conte Dissertation Research Committee: Diana L.E. Johnson, Associate Professor of Biology, Dissertation Co-Director Jill Pecon-Slattery, Staff Scientist, National Cancer Institute, Dissertation Co-Director Diana Lipscomb, Ronald Weintraub Chair and Professor, Committee Member Marc W. Allard, Research Microbiologist, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Committee Member ii Acknowledgements I would like to first thank my advisor and collaborator, Dr. Jill Pecon-Slattery, at the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health, for generously permitting me to join her research group. Without her mentorship this dissertation would never have been possible. I would also like to express gratitude to my advisor at the George Washington University, Dr.