The Representation of Women's Identity in Malayalam Cinema of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Category Wise Provisional Merit List of Eligible Students Subject to Verification of Documents for the Grant of Pragati Scholarship Scheme(Degree) 2018-19 (1St Year)

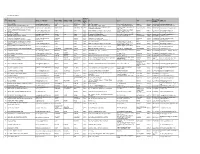

Category wise Provisional Merit List of eligible students subject to verification of documents for the Grant of Pragati Scholarship Scheme(Degree) 2018-19 (1st year) Pragati (Degree)-Nos. of Schlarships-2000 Categor Number of Sl. No. Merit No. ies Students 1 Open 0001-1010 1010 2 OBC 1020-2091 540 3 SC 1019-4474 300 4 ST 1304-6148 90 Pragati open category merit list for the academic year 2018-19(1st yr.) Degree Sl. No. Merit Caste Student Student Father Name Course Name AICTE Institute Institute Name Institute District Institute State No. Category Unique Id Name Permanent ID 1 1 OPEN 2018020874 Gayathri M Madhusoodanan AGRICULTURAL 1-2886013361 KELAPPAJI COLLEGE OF MALAPPURAM Kerala Pillai Pillai K G ENGINEERING AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY, TAVANUR 2 2 OPEN 2018014063 Sreeyuktha ... Achuthakumar K CHEMICAL 1-13392996 GOVERNMENTENGINEERINGCO THRISSUR Kerala R ENGINEERING LLEGETHRISSUR 3 3 OPEN 2018015287 Athira J Radhakrishnan ELECTRICAL AND 1-8259251 GOVT. ENGINEERING COLLEGE, THIRUVANANTHAP Kerala Krishnan S R ELECTRONICS BARTON HILL URAM ENGINEERING 4 4 OPEN 2018009723 Preethi S A Sathyaprakas ARCHITECTURE 1-462131501 COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE THIRUVANANTHAP Kerala Prakash TRIVANDRUM URAM 5 5 OPEN 2018003544 Chaithanya Mohanan K K ELECTRONICS & 1-13392996 GOVERNMENTENGINEERINGCO THRISSUR Kerala Mohan COMMUNICATION LLEGETHRISSUR ENGG 6 6 OPEN 2018015493 Vishnu Priya Gouravelly COMPUTER SCIENCE 1-12344381 UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF HYDERABAD Telangana Gouravelly Ravinder Rao AND ENGINEERING ENGINEERING 7 7 OPEN 2018011302 Pavithra. -

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K. Pandeeswaran No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Intercaste Marriage certificate not enclosed Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 2 AP-2 P. Karthigai Selvi No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Only one ID proof attached. Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 3 AP-8 N. Esakkiappan No.37/45E, Nandhagopalapuram, Above age Thoothukudi – 628 002. 4 AP-25 M. Dinesh No.4/133, Kothamalai Road,Vadaku Only one ID proof attached. Street,Vadugam Post,Rasipuram Taluk, Namakkal – 637 407. 5 AP-26 K. Venkatesh No.4/47, Kettupatti, Only one ID proof attached. Dokkupodhanahalli, Dharmapuri – 636 807. 6 AP-28 P. Manipandi 1stStreet, 24thWard, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Sivaji Nagar, and photo Theni – 625 531. 7 AP-49 K. Sobanbabu No.10/4, T.K.Garden, 3rdStreet, Korukkupet, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Chennai – 600 021. and photo 8 AP-58 S. Barkavi No.168, Sivaji Nagar, Veerampattinam, Community Certificate Wrongly enclosed Pondicherry – 605 007. 9 AP-60 V.A.Kishor Kumar No.19, Thilagar nagar, Ist st, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Chennai -600 019 10 AP-61 D.Anbalagan No.8/171, Church Street, Only one ID proof attached. Komathimuthupuram Post, Panaiyoor(via) Changarankovil Taluk, Tirunelveli, 627 761. 11 AP-64 S. Arun kannan No. 15D, Poonga Nagar, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Ch – 600 019 12 AP-69 K. Lavanya Priyadharshini No, 35, A Block, Nochi Nagar, Mylapore, Only one ID proof attached. Chennai – 600 004 13 AP-70 G. -

Top 10 Male Indian Singers

Top 10 Male Indian Singers 001asd Don't agree with the list? Vote for an existing item you think should be ranked higher or if you are a logged in,add a new item for others to vote on or create your own version of this list. Share on facebookShare on twitterShare on emailShare on printShare on gmailShare on stumbleupon4 The Top Ten TheTopTens List Your List 1Sonu Nigam +40Son should be at number 1 +30I feels that I have goten all types of happiness when I listen the songs of sonu nigam. He is my idol and sometimes I think that he is second rafi thumbs upthumbs down +13Die-heart fan... He's the best! Love you Sonu, your an idol. thumbs upthumbs down More comments about Sonu Nigam 2Mohamed Rafi +30Rafi the greatest singer in the whole wide world without doubt. People in the west have seen many T.V. adverts with M. Rafi songs and that is incediable and mind blowing. +21He is the greatest singer ever born in the world. He had a unique voice quality, If God once again tries to create voice like Rafi he wont be able to recreate it because God creates unique things only once and that is Rafi sahab's voice. thumbs upthumbs down +17Rafi is the best, legend of legends can sing any type of song with east, he can surf from high to low with ease. Equally melodious voice, well balanced with right base and high range. His diction is fantastic, you may feel every word. Incomparable. More comments about Mohamed Rafi 3Kumar Sanu +14He holds a Guinness World Record for recording 28 songs in a single day Awards *. -

Hindi Language and Literature First Degree

HINDI LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE 2017 Admission FIRST DEGREE PROGRAMME IN HINDI Under choice based credit and semester (CBCS) System 2017 Admission onwards 1 Scheme and Syllabi For First Degree Programme in Hindi (Faculty of Oriental Studies) General Scheme Duration : 6 semesters of 18 Weeks/90 working days Total Courses : 36 Total Credits : 120 Total Lecture Hours : 150/Week Evaluation : Continuous Evaluation (CE): 25% Weightage End Semester Evaluation (ESE): 75% (Both the Evaluations by Direct Grading System on a 5 Point scale Summary of Courses in Hindi Course No. of Credits Lecture Type Courses Hours/ Week a. Hindi (For B.A./B.Sc.) Language course : 4 14 18 Additional Language b. Hindi (For B.Com.) Language course : 2 8 8 Additional Language c. First Degree Programme in Hindi Language and Literature Foundation Course 1 3 4 Complementary Course 8 22 24 Core Course 14 52 64 Open Course 2 4 6 Project/Dissertation 1 4 6 A. Outline of Courses B.A./B.Sc. DEGREE PROGRAMMES Course Code Course Type Course Title Credit Lecture Hours/ Week HN 1111.1 Language course (Common Prose And One act 3 4 Course) Addl. Language I ) plays HN 1211.1 Language Course- Common Fiction, Short story, 3 4 (Addl. Language II) Novel HN 1311.1 Language Course- Common Poetry & Grammar 4 5 (Addl. Language III) HN 1411.1 Language Course- Common Drama, Translation 4 5 2 (Addl. Language IV) & Correspondence B.Com. DEGREE PROGRAMME Course Code Course Type Course Title Credit Lecture Hours/ Week HN 1111.2 Language course (Common Prose, Commercial 4 4 Course) Addl. -

Kaloji Narayana Rao University of Health Sciences, Warangal, Telangana State

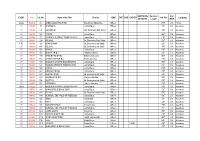

KALOJI NARAYANA RAO UNIVERSITY OF HEALTH SCIENCES, WARANGAL, TELANGANA STATE. MDS ADMISSIONS 2019-20 UNDER COMPETENT AUTHORITY QUOTA FINAL MERIT LIST AFTER VERIFICATION OF ORIGINAL CERTIFICATES AND ADDITION OF SERVICE WEIGHTAGE MARKS Final NEET NEET Service Final Roll Number STUDENT_NAME Gen CAT LOC Service Merit RANK Score weightage Score 1 143 1855208191 651 0 651 P MANISHA JAISWAL F OC OU NS 2 168 1855207911 647 0 647 N.UZWALA F BCD OU NS 3 171 1855218414 647 0 647 KASULA VANI F BCD OU NS 4 203 1855208188 639 0 639 VINEELA PYLA F OC OU NS 5 245 1855208284 634 0 634 G VAISHNAVI F BCB OU NS 6 247 1855207551 633 0 633 DAMA BALAJI M BCB OU NS 7 268 1855218461 629 0 629 PALEM SINDHUSHA F OC OU NS 8 338 1855218605 618 0 618 TALASANI ROJA F OC OU NS 9 367 1855207696 615 0 615 K SUDHEER M BCD OU NS 10 385 1855205215 613 0 613 GANGAVARAPU ESWAR KOWSIK M OC AU NS 11 404 1855207841 611 0 611 BHARAT CHANDRA V M OC OU NS 12 418 1855205315 609 0 609 SWAPNIKA SUBRAMANYAM GUDAPATI F OC AU NS 13 2467 1855207520 487 116.88 603.88 RESHMA Y F BCD SVU Service 14 475 1855207465 601 0 601 BAKKA RISHIKA F OC OU NS 15 606 1855218530 587 0 587 RAYAPATI NAMRATHA F OC OU NS 16 610 1855207431 587 0 587 RACHANVALE HAFSA PARVEEN F BCE SVU NS 17 655 1855208313 582 0 582 YERRAM HARSHITHA LAKSHMI F OC OU NS 18 662 1855207760 582 0 582 KONDOJ NAVYA SREE F BCB OU NS 19 720 1855207974 577 0 577 SWATHI MAMATHA G F BCD OU NS 20 732 1855218310 576 0 576 BRAHMANDAM ROHINI PRAVALLIKA F OC OU NS 21 772 1855220967 574 0 574 CHILLARA DIVYASREE F OC OU NS 22 778 1855207944 573 -

List of Nodal Officer

List of Nodal Officer Designa S.No tion of Phone (With Company Name EMAIL_ID_COMPANY FIRST_NAME MIDDLE_NAME LAST_NAME Line I Line II CITY PIN Code EMAIL_ID . Nodal STD/ISD) Officer 1 VIPUL LIMITED [email protected] PUNIT BERIWALA DIRT Vipul TechSquare, Golf Course Road, Sector-43, Gurgaon 122009 01244065500 [email protected] 2 ORIENT PAPER AND INDUSTRIES LTD. [email protected] RAM PRASAD DUTTA CSEC BIRLA BUILDING, 9TH FLOOR, 9/1, R. N. MUKHERJEE ROAD KOLKATA 700001 03340823700 [email protected] COAL INDIA LIMITED, Coal Bhawan, AF-III, 3rd Floor CORE-2,Action Area-1A, 3 COAL INDIA LTD GOVT OF INDIA UNDERTAKING [email protected] MAHADEVAN VISWANATHAN CSEC Rajarhat, Kolkata 700156 03323246526 [email protected] PREMISES NO-04-MAR New Town, MULTI COMMODITY EXCHANGE OF INDIA Exchange Square, Suren Road, 4 [email protected] AJAY PURI CSEC Multi Commodity Exchange of India Limited Mumbai 400093 0226718888 [email protected] LIMITED Chakala, Andheri (East), 5 ECOPLAST LIMITED [email protected] Antony Pius Alapat CSEC Ecoplast Ltd.,4 Magan Mahal 215, Sir M.V. Road, Andheri (E) Mumbai 400069 02226833452 [email protected] 6 ECOPLAST LIMITED [email protected] Antony Pius Alapat CSEC Ecoplast Ltd.,4 Magan Mahal 215, Sir M.V. Road, Andheri (E) Mumbai 400069 02226833452 [email protected] 7 NECTAR LIFE SCIENCES LIMITED [email protected] SUKRITI SAINI CSEC NECTAR LIFESCIENCES LIMITED SCO 38-39, SECTOR 9-D CHANDIGARH 160009 01723047759 [email protected] 8 ECOPLAST LIMITED [email protected] Antony Pius Alapat CSEC Ecoplast Ltd.,4 Magan Mahal 215, Sir M.V. Road, Andheri (E) Mumbai 400069 02226833452 [email protected] 9 SMIFS CAPITAL MARKETS LTD. -

EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P

UMATIC/DG Duration/ Col./ EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P. B.) Man Mohan Mahapatra 06Reels HST Col. Oriya I. P. 1982-83 73 APAROOPA Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1985-86 201 AGNISNAAN DR. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1986-87 242 PAPORI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 252 HALODHIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 294 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 06Reels EST Col. Assamese F.O.I. 1985-86 429 AGANISNAAN Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 440 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 06Reels SST Col. Assamese I. P. 1989-90 450 BANANI Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 483 ADAJYA (P. B.) Satwana Bardoloi 05Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 494 RAAG BIRAG (P. B.) Bidyut Chakravarty 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 500 HASTIR KANYA(P. B.) Prabin Hazarika 03Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 509 HALODHIA CHORYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 522 HALODIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels FST Col. Assamese I. P. 1990-91 574 BANANI Jahnu Barua 12Reels HST Col. Assamese I. P. 1991-92 660 FIRINGOTI (P. B.) Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1992-93 692 SAROTHI (P. B.) Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 05Reels EST Col. -

WWS Report 2019-2020

Sree Narayana College, Kollam Detailed Annual Activity Report of WalkWith A Scholar – 2019-2020 Walk With A Scholar programme for the year started with the coordinator meeting organized by the Director, DCE, to provide clarity regarding fund transfer procedure of WWS on 11/6/2019 at Loyola College, Sreekaryam. Also the general outline of the programme for the academic year (2019-2020) was also discussed.This was followed by another One Day Coordinator's meet on a Zonal basis at Government Women’s College, Vazhuthacaud, Thiruvananthapuram on 29/08/2019 and 30/08/2019. A monitoring committee was formed to manage and monitor the activities of WWS programme of the college. All activities of the WWS programme was presented and approved by the council. External Mentoring Sessions for First Year Date Name of the Mentor Topic 04-01-2020 M.C Rajilan Identify top three personal strengths Develop three personal strengths Goal setting Swot Analysis 06-01-2020 Mahesh T Art of Self development 11-01-2020 Harikrishnan R S Developing scientific temper 11-01-2020 Akhiles U How to read and review an academic book 25-01-2020 Adv Sabitha Beegum Understanding Constitution and democracy List of the First year WWS students 2019-2020 List of the First year WWS students 2019-2020 Sl Name of Permanent address Course Plus two Mentor’s name No student marks 1. Sabari.G.Das Theertham B 955 Nisha.V.S Thachodu Sc,Zoology Muttapalam.P.O Varkala 2. Subhalakshm Kunnil veedu B 1136 Nisha.V.S i Mukkattukunnu Sc,Zoology Chirakkarathazham. P.O Kollam 3. -

High Court of Delhi Advance Cause List

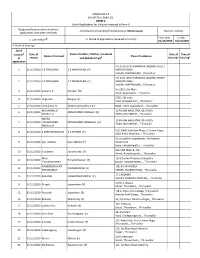

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR th WEDNESDAY, THE 29 JANUARY, 2020 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 01 TO 62 2. COMPANY JURISDICTION 63 TO 73 3. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 74 TO 85 4. REGISTRAR GENERAL/ 86 TO 104 REGISTRAR (APPLT.)/ REGISTRAR (LISTING)/ REGISTRAR(ORGL.)/ JOINT REGISTRARS(ORGL). 29.01.2020 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) 29.01.2020 [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-I) HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE C.HARI SHANKAR FRESH MATTERS & APPLICATIONS ______________________________ 1. ITA 45/2020 PR. COMMISSIONER OF INCOME ZOHEB HOSSAIN CM APPL. 3017/2020 TAX- (CENTRAL-II) CM APPL. 3018/2020 Vs. M/S ETT LIMITED (FORMERLY KNOWN AS INDIAN EXPRESS MULTIMEDIA LTD.) 2. W.P.(C) 154/2020 M/S MANAVI EXIM PVT. LTD. PREM RAJAN KUMAR CM APPL. 413/2020 Vs. THE ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER OF CUSTOMS, ICD, FOR ADMISSION _______________ 3. CUSAA 229/2019 ADDTIONAL DIRECTOR AJIT SHARMA CAV 1231/2019 GENERAL(ADJUDICATION) CAV 1232/2019 Vs. M/S IT'S MY NAME PVT LTD CAV 1233/2019 CAV 1234/2019 CAV 1235/2019 CM APPL. 53876/2019 CM APPL. 53877/2019 CM APPL. 53878/2019 4. W.P.(C) 864/2020 PRABIR GHOSH FARAZ KHAN CM APPL. 2698/2020 Vs. COMMISSIONER OF CUSTOMS, CM APPL. 2706/2020 ICD, PATPARGANJ 5. W.P.(C) 882/2020 PRABIR GHOSH FARAZ KHAN CM APPL. 2792/2020 Vs. COMMISSIONER OF CUSTOMS, CM APPL. 2793/2020 ICD, PATPARGANJ AFTER NOTICE MISC. -

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applica Ons For

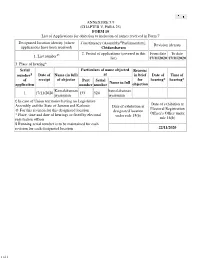

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applicaons for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated locaon identy (where Constuency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Maduravoyal Revision identy applicaons have been received) From date To date @ 2. Period of applicaons (covered in this list) 1. List number 01/12/2020 01/12/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial $ Date of Name of Father / Mother / Husband Date of Time of number Name of claimant Place of residence of receipt and (Relaonship)# hearing* hearing* applicaon NO 27/A, DEVI NARAYANA LAKSHMI STREET 1 01/12/2020 C E PRAKASAN C E NARAYANAN (F) MARUTHI RAM NAGAR, AYAPPAKKAM, , Thiruvallur NO 27/A, DEVI NARAYANA LAKSHMI STREET 2 01/12/2020 C E PRAKASAN C E NARAYANAN (F) MARUTHI RAM NAGAR, AYAPPAKKAM, , Thiruvallur No 2319, 5th Main 3 01/12/2020 Sumathi R Ramesh (H) Road, Ayapakkam, , Thiruvallur 2785, 5th main 4 01/12/2020 Jaiganesh Rangan (F) road, Ayyappakkam, , Thiruvallur 5 01/12/2020 Hemalatha D Dhatshinamoorthy K (H) 8640, TNHB, Ayapakkam, , Thiruvallur MOHAMMED 10 FA JAIN NAKSHTRA, 86 UNION 6 01/12/2020 MOHAMMED NORULLA (F) NASRULLA ROAD, NOLAMBUR, , Thiruvallur HAJIRA 10 FA JAIN NAKSHTRA, 86 UNION 7 01/12/2020 MOHAMMED MOHAMMED NASRULLA (H) ROAD, NOLAMBUR, , Thiruvallur NASRULLA C16, DABC Gokulam Phase 3, Sriram Nagar 8 01/12/2020 S SURIYAKRISHNAN K S SATHISH (F) Main Road, Nolambur, , Thiruvallur 42 sri Lakshmi apartments, 3rd Avenue 9 01/12/2020 sijo mathew biju mathew (F) millennium town, adayalampau, , Thiruvallur 312 VNR Milford, 7th 10 01/12/2020 Sundaram savarimuthu (F) Street, -

Twenty 20 Malayalam Full Movie

Twenty 20 malayalam full movie Continue Twenty:20Official theatrical posterFoshiProduced byDileep Written byUdayakrishnaSiby K. ThomasStarringMohanlalMammoottySuresh GopiJayaramDileepMusic fromSur PetereshsBerny IgnatiusCinematographyP.SukumarEditedRan by Abraham Abraham and production DistributedManjunatha release Kalasangham FilmsRelease date November 5, 2008 (2008-11-05) Duration 165 minutesCountryIndiaLanguageMalayalamBudget₹7 crore (US$980,000)Box officeest. ₹32.6 crora ($4.6 million) is a 2008 Indian action film in Malayalam, written by Udayakrishna and Sibi K. Thomas and directed by Josh. The film stars Mohanlal, Mammutti, Suresh Gopi, Jayaram and Dillep, and was produced and distributed by actor Dillep through Graand Production and Manjunatha Release. The film was produced on behalf of the Association of Malayalam Film Chronicles (AMMA) as a fundraiser to financially support actors who are struggling in the Malayalam film industry. All AMMA members worked without pay to raise funds for their Social Security programs. The film features an ensemble of actors, which includes almost all AMMA artists. The music was written by Bernie-Ignatius and Suresh Peters. The share of the first two weeks of the film's distributors was ₹5.72 crore ($800,000). The film managed to gain a foothold in the third position (with 7 prints, 4 in Chennai) in the box office of Tamil Nadu in the first week. The total number of introductory engravings produced inside Kerala was 117; some 25 prints were released outside Kerala on November 21, 2008, including 4 prints in the United States and 11 engravings in the UAE. The film grossed a total of ₹32.6 kronor ($4.6 million). It was the highest-grossing film in Malayalam cinema until 2013. -

ANNEXURE 5.9 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 10 List of Applications For

ANNEXURE 5.9 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 10 List of Applications for objection to inclusion of names received in Form 7 Designated location identity (where £ Constituency (Assembly/ Parliamentary): Revision identity applications have been received) Chidambaram @ 2. Period of applications (covered in this From date To date 1. List number list) 17/11/2020 17/11/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial Particulars of name objected Reasons number $ Date of Name (in full) at in brief Date of Time of of receipt of objector Part Serial for hearing* hearing* Name in full application number number objection Kamalakannan kamalakannan 1 17/11/2020 133 524 jayaraman jayaraman £ In case of Union territories having no Legislative Date of exhibition at Assembly and the State of Jammu and Kashmir Date of exhibition at Electoral Registration @ For this revision for this designated location designated location Officer's Office under * Place, time and date of hearings as fixed by electoral under rule 15(b) registration officer rule 16(b) $ Running serial number is to be maintained for each revision for each designated location 22/11/2020 1 of 1 ANNEXURE 5.9 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 10 List of Applications for objection to inclusion of names received in Form 7 Constituency Designated location identity (where £ Revision identity applications have been received) (Assembly/ Parliamentary): Chidambaram @ 2. Period of applications (covered in this From date To date 1. List number list) 19/11/2020 19/11/2020 3. Place of hearing* Particulars of name Serial Name (in Reasons