Core 1..48 Committee (PRISM::Advent3b2 17.25)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada Gazette, Part I

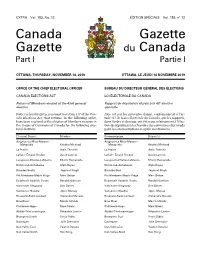

EXTRA Vol. 153, No. 12 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 153, no 12 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2019 OTTAWA, LE JEUDI 14 NOVEMBRE 2019 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER BUREAU DU DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 43rd general Rapport de député(e)s élu(e)s à la 43e élection election générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Can- Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’ar- ada Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, ticle 317 de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, have been received of the election of Members to serve in dans l’ordre ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élec- the House of Commons of Canada for the following elec- tion de député(e)s à la Chambre des communes du Canada toral districts: pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral District Member Circonscription Député(e) Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Matapédia Kristina Michaud Matapédia Kristina Michaud La Prairie Alain Therrien La Prairie Alain Therrien LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Burnaby South Jagmeet Singh Burnaby-Sud Jagmeet Singh Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke Randall Garrison Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke -

List of Mps on the Hill Names Political Affiliation Constituency

List of MPs on the Hill Names Political Affiliation Constituency Adam Vaughan Liberal Spadina – Fort York, ON Alaina Lockhart Liberal Fundy Royal, NB Ali Ehsassi Liberal Willowdale, ON Alistair MacGregor NDP Cowichan – Malahat – Langford, BC Anthony Housefather Liberal Mount Royal, BC Arnold Viersen Conservative Peace River – Westlock, AB Bill Casey Liberal Cumberland Colchester, NS Bob Benzen Conservative Calgary Heritage, AB Bob Zimmer Conservative Prince George – Peace River – Northern Rockies, BC Carol Hughes NDP Algoma – Manitoulin – Kapuskasing, ON Cathay Wagantall Conservative Yorkton – Melville, SK Cathy McLeod Conservative Kamloops – Thompson – Cariboo, BC Celina Ceasar-Chavannes Liberal Whitby, ON Cheryl Gallant Conservative Renfrew – Nipissing – Pembroke, ON Chris Bittle Liberal St. Catharines, ON Christine Moore NDP Abitibi – Témiscamingue, QC Dan Ruimy Liberal Pitt Meadows – Maple Ridge, BC Dan Van Kesteren Conservative Chatham-Kent – Leamington, ON Dan Vandal Liberal Saint Boniface – Saint Vital, MB Daniel Blaikie NDP Elmwood – Transcona, MB Darrell Samson Liberal Sackville – Preston – Chezzetcook, NS Darren Fisher Liberal Darthmouth – Cole Harbour, NS David Anderson Conservative Cypress Hills – Grasslands, SK David Christopherson NDP Hamilton Centre, ON David Graham Liberal Laurentides – Labelle, QC David Sweet Conservative Flamborough – Glanbrook, ON David Tilson Conservative Dufferin – Caledon, ON David Yurdiga Conservative Fort McMurray – Cold Lake, AB Deborah Schulte Liberal King – Vaughan, ON Earl Dreeshen Conservative -

MOVING FORWARD – TOWARDS a STRONGER CANADIAN MUSEUM SECTOR Report of the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage

MOVING FORWARD – TOWARDS A STRONGER CANADIAN MUSEUM SECTOR Report of the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage Julie Dabrusin, Chair SEPTEMBER 2018 42nd PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION Published under the authority of the Speaker of the House of Commons SPEAKER’S PERMISSION The proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees are hereby made available to provide greater public access. The parliamentary privilege of the House of Commons to control the publication and broadcast of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees is nonetheless reserved. All copyrights therein are also reserved. Reproduction of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees, in whole or in part and in any medium, is hereby permitted provided that the reproduction is accurate and is not presented as official. This permission does not extend to reproduction, distribution or use for commercial purpose of financial gain. Reproduction or use outside this permission or without authorization may be treated as copyright infringement in accordance with the Copyright Act. Authorization may be obtained on written application to the Office of the Speaker of the House of Commons. Reproduction in accordance with this permission does not constitute publication under the authority of the House of Commons. The absolute privilege that applies to the proceedings of the House of Commons does not extend to these permitted reproductions. Where a reproduction includes briefs to a Standing Committee of the House of Commons, authorization for reproduction may be required from the authors in accordance with the Copyright Act. Nothing in this permission abrogates or derogates from the privileges, powers, immunities and rights of the House of Commons and its Committees. -

Core 1..44 Committee (PRISM::Advent3b2 17.25)

Standing Committee on the Status of Women FEWO Ï NUMBER 077 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 42nd PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE Tuesday, November 7, 2017 Chair Mrs. Karen Vecchio 1 Standing Committee on the Status of Women Tuesday, November 7, 2017 Women are key decision-makers in Canadian households. Women are influencers of our next generation of scientists, technologists, Ï (1100) engineers, and mathematicians. Actually, women represent the larger [English] proportion of educators in our classrooms. The Chair (Mrs. Karen Vecchio (Elgin—Middlesex—London, Because technology is an ongoing and ever-growing driver of CPC)): Everybody, we're going to get started. We look to have a innovation within multiple industries, we have an opportunity as a quorum here. Some members will be joining us shortly. We're going nation to minimize the gender gap and to ensure that we are working to continue with our study of the economic security of women in towards a more prosperous and unified nation. Canada. Today we will have two guests on our first panel. How can we address this issue? There is no one causal factor. It is very complex, very systemic, and therefore there is no one solution Carolyn Van is the director of youth programming for Canada to all of this. Learning Code. Bonnie Brayton will be here shortly. What we do know, however, is that the causes of the gender gap in We may have to mix it up a little until our second panellist gets technology have nothing to do with biological differences. In fact, here. After the presentation, we may go to questions, but we'll see while many of us doubt it, there have been numerous research how it goes. -

Core 1..68 Committee (PRISM::Advent3b2 17.25)

Standing Committee on Finance FINA Ï NUMBER 105 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 42nd PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE Monday, September 25, 2017 Chair The Honourable Wayne Easter 1 Standing Committee on Finance Monday, September 25, 2017 should take a page from the successful tax incentive program used in the United Kingdom, which specifically incents small and medium- Ï (1530) sized business enterprises to engage in a first apprenticeship [English] experience. We think the federal government is best positioned to The Chair (Hon. Wayne Easter (Malpeque, Lib.)): I call the do that by enhancing the apprenticeship job creation tax credit that is meeting to order. already in existence. As witnesses know, just for the record, pursuant to Standing Order 83.1, we're dealing with pre-budget consultations in advance of the As to supporting labour mobility, most employers will reimburse 2018 budget, and we have six panellists here. an employee, once hired, to relocate. But what about cases in which there is no compensation or in which an EI recipient needs help to Welcome. Thank you for coming. As well, I want to thank those— travel to look for work? It is estimated by the building trade unions I think most of you—who have presented submissions prior to the that a tradesperson can incur $3,500 annually in non-compensable mid-August deadline. mobility expenses, presenting a significant obstacle to moving We we will start with the Canadian Construction Association, Mr. outside their local labour markets. We believe that a change to EI Atkinson. policy to permit unemployed construction workers on EI to obtain an advance from their approved benefits to support employment I might say as well that if you can hold your comments to about searches outside their local area would do a great deal to incent five minutes, that would be helpful; then we have more time for labour mobility. -

Charitable Registration Number: 10684 5100 RR0001 Hon. Patty Hajdu Minister of Health Government of Canada February 27, 2021

Cystic Fibrosis Canada Ontario Suite 800 – 2323 Yonge Street Toronto, ON M4P 2C9 416.485.9149 ext. 297 [email protected] www.cysticfibrosis.ca Hon. Patty Hajdu Minister of Health Government of Canada February 27, 2021 Dear Minister Hajdu, We are members of an all-party caucus on emergency access to Trikafta, a game-changing therapy that can treat 90% of the cystic fibrosis population. We are writing to thank you for your commitment to fast- tracking access to Trikafta and to let you know that we are here to collaborate with you in this work. We know that an application for review of Trikafta was received by Health Canada on December 4th, 2020 and was formally accepted for review on December 23rd. We are also aware that the Canadian Agency for Drugs Technologies in Health (CADTH) body that evaluates the cost effectiveness of drugs is now reviewing Trikafta for age 12 plus for patients who have at least one F508del mutation. This indicates that Trikafta was granted an ‘aligned review,’ the fastest review route. The aligned review will streamline the review processes by the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) to set the maximum amount for which the drug can be sold, and by Health Technology Assessment bodies (CADTH and INESSS) to undertake cost-effective analyses, which can delay the overall timeline to access to another 6 months or more. An aligned review will reduce the timelines of all of these bodies to between 8-12 months or sooner. But that is just one half of the Canadian drug approval system. -

Canada Gazette, Part I, Extra

EXTRA Vol. 149, No. 7 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 149, no 7 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 3, 2015 OTTAWA, LE MARDI 3 NOVEMBRE 2015 CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 42nd general election Rapport de député(e)s élu(e)s à la 42e élection générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Canada Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’article 317 Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, have been de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, dans l’ordre received of the election of Members to serve in the House of Com- ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élection de député(e)s à mons of Canada for the following electoral districts: la Chambre des communes du Canada pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral Districts Members Circonscriptions Député(e)s Saint Boniface—Saint Vital Dan Vandal Saint-Boniface—Saint-Vital Dan Vandal Whitby Celina Whitby Celina Caesar-Chavannes Caesar-Chavannes Davenport Julie Dzerowicz Davenport Julie Dzerowicz Repentigny Monique Pauzé Repentigny Monique Pauzé Salaberry—Suroît Anne Minh-Thu Quach Salaberry—Suroît Anne Minh-Thu Quach Saint-Jean Jean Rioux Saint-Jean Jean Rioux Beloeil—Chambly Matthew Dubé Beloeil—Chambly Matthew Dubé Terrebonne Michel Boudrias Terrebonne Michel Boudrias Châteauguay—Lacolle Brenda Shanahan Châteauguay—Lacolle Brenda Shanahan Ajax Mark Holland Ajax Mark Holland Oshawa Colin Carrie Oshawa -

We Put This Together for You and We're Sending It to You Early

Exclusively for subscribers of The Hill Times We put this together for you and we’re sending it to you early. 1. Certified election 2019 results in all 338 ridings, top four candidates 2. The 147 safest seats in the country 3. The 47 most vulnerable seats in the country 4. The 60 seats that flipped in 2019 Source: Elections Canada and complied by The Hill Times’ Samantha Wright Allen THE HILL TIMES | MONDAY, NOVEMBER 11, 2019 13 Election 2019 List Certified 2019 federal election results 2019 2019 2019 2019 2019 2019 Votes Votes% Votes Votes% Votes Votes% ALBERTA Edmonton Riverbend, CPC held BRITISH COLUMBIA Banff-Airdrie, CPC held Matt Jeneroux, CPC 35,126 57.4% Tariq Chaudary, LPC 14,038 23% Abbotsford, CPC held Blake Richards, CPC 55,504 71.1% Ed Fast, CPC 25,162 51.40% Audrey Redman, NDP 9,332 15.3% Gwyneth Midgley, LPC 8,425 10.8% Seamus Heffernan, LPC 10,560 21.60% Valerie Kennedy, GRN 1,797 2.9% Anne Wilson, NDP 8,185 10.5% Madeleine Sauvé, NDP 8,257 16.90% Austin Mullins, GRN 3,315 4.2% Stephen Fowler, GRN 3,702 7.60% Edmonton Strathcona, NDP held Battle River-Crowfoot, CPC held Heather McPherson, NDP 26,823 47.3% Burnaby North-Seymour, LPC held Sam Lilly, CPC 21,035 37.1% Damien Kurek, CPC 53,309 85.5% Terry Beech, LPC 17,770 35.50% Eleanor Olszewski, LPC 6,592 11.6% Natasha Fryzuk, NDP 3,185 5.1% Svend Robinson, NDP 16,185 32.30% Michael Kalmanovitch, GRN 1,152 2% Dianne Clarke, LPC 2,557 4.1% Heather Leung, CPC 9,734 19.40% Geordie Nelson, GRN 1,689 2.7% Amita Kuttner, GRN 4,801 9.60% Edmonton West, CPC held Bow River, CPC held -

LOBBY MONIT R the 43Rd Parliament: a Guide to Mps’ Personal and Professional Interests Divided by Portfolios

THE LOBBY MONIT R The 43rd Parliament: a guide to MPs’ personal and professional interests divided by portfolios Canada currently has a minority Liberal government, which is composed of 157 Liberal MPs, 121 Conservative MPs, 32 Bloc Québécois MPs, 24 NDP MPs, as well as three Green MPs and one Independent MP. The following lists offer a breakdown of which MPs have backgrounds in the various portfolios on Parliament Hill. This information is based on MPs’ official party biographies and parliamentary committee experience. Compiled by Jesse Cnockaert THE LOBBY The 43rd Parliament: a guide to MPs’ personal and professional interests divided by portfolios MONIT R Agriculture Canadian Heritage Children and Youth Education Sébastien Lemire Caroline Desbiens Kristina Michaud Lenore Zann Louis Plamondon Martin Champoux Yves-François Blanchet Geoff Regan Yves Perron Marilène Gill Gary Anandasangaree Simon Marcil Justin Trudeau Claude DeBellefeuille Julie Dzerowicz Scott Simms Filomena Tassi Sean Casey Lyne Bessette Helena Jaczek Andy Fillmore Gary Anandasangaree Mona Fortier Lawrence MacAulay Darrell Samson Justin Trudeau Harjit Sajjan Wayne Easter Wayne Long Jean-Yves Duclos Mary Ng Pat Finnigan Mélanie Joly Patricia Lattanzio Shaun Chen Marie-Claude Bibeau Yasmin Ratansi Peter Schiefke Kevin Lamoureux Francis Drouin Gary Anandasangaree Mark Holland Lloyd Longfield Soraya Martinez Bardish Chagger Pablo Rodriguez Ahmed Hussen Francis Scarpaleggia Karina Gould Jagdeep Sahota Steven Guilbeault Filomena Tassi Kevin Waugh Richard Lehoux Justin Trudeau -

Party Name Riding Province Email Phone Twitter Facebook

Party Name Riding Province Email Phone Twitter Facebook NDP Joanne Boissonneault Banff-Airdrie Alberta https://twitter.com/AirdrieNDP Liberal Marlo Raynolds Banff–Airdrie Alberta [email protected] 587.880.3282 https://twitter.com/MarloRaynolds https://www.facebook.com/voteMarlo Conservative BLAKE RICHARDS Banff—Airdrie Alberta [email protected] 877-379-9597 https://twitter.com/BlakeRichardsMP https://www.facebook.com/blakerichards.ca Conservative KEVIN SORENSON Battle River—Crowfoot Alberta [email protected] (780) 608-6362 https://twitter.com/KevinASorenson https://www.facebook.com/sorensoncampaign2015 Conservative MARTIN SHIELDS Bow River Alberta [email protected] (403) 793-1252 https://twitter.com/MartinBowRiver https://www.facebook.com/MartininBowRiver Conservative Joan Crockatt Calgary Centre Alberta [email protected] 587-885-1728 https://twitter.com/Crockatteer https://www.facebook.com/joan.crockatt Liberal Kent Hehr Calgary Centre Alberta [email protected] 403.475.4474 https://twitter.com/KentHehr www.facebook.com/kenthehrj NDP Jillian Ratti Calgary Centre Alberta Conservative LEN WEBBER Calgary Confederation Alberta [email protected] (403) 828-1883 https://twitter.com/Webber4Confed https://www.facebook.com/lenwebberyyc Liberal Matt Grant Calgary Confederation Alberta [email protected] 403.293.5966 www.twitter.com/MattAGrant www.facebook.com/ElectMattGrant NDP Kirk Heuser Calgary Confederation Alberta https://twitter.com/KirkHeuser Conservative DEEPAK OBHRAI Calgary Forest Lawn Alberta [email protected] -

Members of Parliament with Anti-Choice Stance, and Unknown

Members of Parliament with an Anti-choice Stance October 16, 2019 By Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada History: After 2015 election (last updated May 2016) Prior to 2015 election (last updated Feb 2015) After May 2011 election (last updated Sept 2012) After 2008 election (last updated April 2011) Past sources are listed at History links. Unknown or Party Total MPs Anti-choice MPs** Pro-choice MPs*** Indeterminate Stance Liberal 177 6* (3.5%) 170* (96%) 1 Conservative 95 76 (80%) 8 (8%) 11 (12%) NDP 39 0 39 0 Bloc Quebecois 10 0 10 0 Independent 8 1 6 1 Green 2 0 2 0 Co-operative 1 0 1 0 Commonwealth Federation People’s Party 1 1 0 Vacant (5) Total 333 84 (25%) 236 (71%) 13 (4%) (not incl. vacant) (Excluding Libs/PPC: 23%) *All Liberal MPs have agreed and will be required to vote pro-choice on any abortion-related bills/motions. Also, Trudeau will not likely allow anti-choice MPs to introduce their own bills/motions, or publicly advocate against abortion rights. Therefore, these MPs should not pose any threat, although they should be monitored. Likewise, Liberal MPs not on this 2014 pro-choice list may warrant monitoring to ensure they adhere to the party’s pro-choice policy. Oct 2016, Bill C-225 update: All 7 Liberals with previous anti-choice records voted No, except for John McKay who did not vote. **Anti-choice MPs are designated as anti-choice based on at least one of these reasons: • Voted in favour of Bill C-225, and/or Bill C-484, and/or Bill C-510, and/or Motion 312 • Opposed the Order of Canada for Dr. -

Letter to the Province from Rocky View

Office of the Reeve 262075 Rocky View Point Rocky View County, AB | T4A 0X2 www.rockyview.ca January 11, 2019 Government of Alberta Offices of the Ministers Transportation / Environment and Parks via email: [email protected]; [email protected] Dear Ministers Mason and Phillips, The 2013 Elbow River Flood caused severe property damage to Rocky View County and the City of Calgary, and threatened the community of Redwood Meadows. Rocky View County recognizes and supports the need for flood protection for all of these communities. I’m writing to officially inform you of Rocky View County Council’s position that we cannot support the Springbank Dry Dam (SR-1) option as a means of flood mitigation until all other options are equally evaluated and regional needs are fully considered. This was not a decision made lightly. In choosing SR1 as the primary means of flood protection, it clear to us that: other options such as the Priddis diversion and McLean Creek were not given the same level of technical evaluation as SR-1; value-based decisions - without public input - were used to justify SR1 over MC-1; e.g. agriculture and rural homes are less important than recreation and tourism, and full deliberation on the benefits of a wet dam for drought protection and water deliverability did not occur. Additionally, new information has come forward, including: the rising costs of SR-1, which have eliminated the cost-benefit difference with the McLean Creek option; and The new alternative storage solution proposed by the Tsuut’ina Nation.