Monetising the Impacts of Waste Incinerators Sited on Brownfield Land Using the Hedonic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marchwood Power Limited Marchwood Power Station Oceanic Way Marchwood Industrial Park Marchwood Southampton SO40 4BD

Notice of variation and consolidation with introductory note The Environmental Permitting (England & Wales) Regulations 2016 Marchwood Power Limited Marchwood Power Station Oceanic Way Marchwood Industrial Park Marchwood Southampton SO40 4BD Variation application number EPR/BL6217IM/V010 Permit number EPR/BL6217IM Variation and consolidation application number EPR/BL6217IM/V010 1 Marchwood Power Station Permit number EPR/BL6217IM Introductory note This introductory note does not form a part of the notice. Under the Environmental Permitting (England & Wales) Regulations 2016 (schedule 5, part 1, paragraph 19) a variation may comprise a consolidated permit reflecting the variations and a notice specifying the variations included in that consolidated permit. Schedule 2 of the notice comprises a consolidated permit which reflects the variations being made. All the conditions of the permit have been varied and are subject to the right of appeal. Purpose of this variation: Article 21(3) of the Industrial Emissions Directive (IED) requires the Environment Agency to review conditions in permits that it has issued and to ensure that the permit delivers compliance with relevant standards, within four years of the publication of updated decisions on Best Available Techniques (BAT) Conclusions. We have reviewed the permit for this installation against the revised BAT Conclusions for the large combustion plant sector published on 17th August 2017. Only activities covered by this BAT Reference Document have been reviewed and assessed. This variation makes the below changes following the review under Article 21(3) of the IED and the consolidation of the Environmental Permitting Regulations that came into force on the 4 January 2017: Revised emission limits and monitoring requirements for emissions to air applicable from 17 August 2021 in table S3.1a; Inclusion of process monitoring for energy efficiency in table S3.4. -

(Public) 17/09/2013, 17.00

Public Document Pack CABINET DOCUMENTS FOR THE MEMBERS ROOM Tuesday, 17th September, 2013 at 5.00 pm MEMBERS ROOM DOCUMENTS ATTACHED TO THE LISTED REPORTS Contacts Cabinet Administrator Judy Cordell Tel: 023 8083 2766 Email: [email protected] MEMBERS ROOM DOCUMENTS 14 HAMPSHIRE MINERALS AND WASTE PLAN: ADOPTION Inspectors’ report into the Hampshire Minerals and Waste Plan (2013). Saved policies of the Minerals and Waste Local Plan (1998). Minerals and Waste Core Strategy (2007). Minerals and Waste Plan for adoption (2013). Inspector’s ‘Main Modifications’. Inspector’s ‘Additional Modifications’. Hampshire County Council’s Cabinet report. List of Southampton sites in background document potentially suitable for waste management facilities. Summary of consultation responses (2013). Monday, 9 September HEAD OF LEGAL , HR AND DEMOCRATIC SERVICES 2013 Agenda Item 14 Report to Hampshire County Council, Portsmouth City Council, Southampton City Council, New Forest National Park Authority and South Downs National Park Authority by Andrew S Freeman, BSc(Hons) DipTP DipEM FRTPI FCIHT MIEnvSc an Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government rd Date : 23 May 2013 PLANNING AND COMPULSORY PURCHASE ACT 2004 (AS AMENDED) SECTION 20 REPORT ON THE EXAMINATION INTO THE HAMPSHIRE MINERALS AND WASTE PLAN LOCAL PLAN Document submitted for examination on 29 February 2012 Examination hearings held between 6 to 8 June 2012, 11 to 15 June 2012 and 13 to 14 March 2013 File Ref: PINS/Q1770/429/7 ABBREVIATIONS USED -

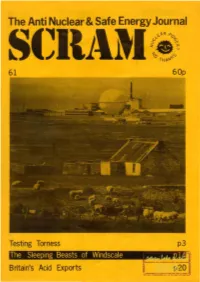

Testing Torness Britain's Acid Exports

61 Testing Torness p3 Britain's Acid Exports CONTENTS COMMENT Testing Torness 3 At the time of writing, Edinburgh is in the PETE ROCHE gives o round-up of recent middle of the Internat ional Festival •. This events a t our own local nuke. News 4-8 always brings anti-nuclear visitors from groups Chernobyl ond the Media. 9 all over the world, on holiday but not above THOM DIBDIN report$ from the Ecovision a visit to SCRAM to tell of a demonstration '87 Conference. at Wackersdorf (8-10 Oct }, or to discuss views As Safe os Houses? 1·1 PATRICK GREEN discusses the Government's on privatisation. We've also been visited by half-heorted a ttempts to solve the roovn the Greenpeoce boat, Moby Dick, on it s way gos problem. up to Dounreay to collect some samples for Trumpets & Raspbe rries 12-13 radiat ion monitoring. As usual t here is a spate STEYE MARTIN compares the triumphant Dounreay Inquiry Report with the gloomy of anti-nuclear ploys; t heatre groups wanting truth of some UKAEA leaked documents. discounts on their photocopying and demanding The Sleeping Beasts of Wl ndscole 14-15 attendance at their latest product ion which is JOHN LARGE ond PAUL DRAPER explain going to change the world. the problems which led to the notorious 1957 Wlndscale Fire. We always remind visitors that this wlll Breeder Bombs Out 16-17 be the last nuclear- free Festival in these part s MYCLE SCHNEIDER assesses the future if Torness starts up according to the SSEB's of the fast reactor fuel cycle ond latest amended schedule. -

He Chairman of British Aluminium Blamed the Closure Squarely On

- he Chairman of British Aluminium yest ~rday blamed the closure squarely on high power costs . ....... Contents -------Comment______ _ lnvergordon and Nukes 3 News 4-5 Waste Dumping - final? 6 Energy Politics Namibia and RTZ 7 PWR's and Sizewell 8-9 The closure of the aluminium smelter at lnvergordon shows that economics Consumer Campaign 10 and energy policy are Intimately linked. The energy policy of the current Govern ment Is based on the economics of unemployment. An energy policy which is Insulation Programme 11 inflationary can only lead to increased hardship for low Income groups. Appropriate Tech- 12-13 This Issue of the Energy ISulletin Is all about the· worst effects of such a policy, nology which spreads to the Third World, creating a poverty trap In places like Namibia [see page 7]. Reviews 14 The intransigent policies of this Government blunder onward, with the pro SCRAM 15 posed Pressurised Water Reactor at Slzewell in East Anglia raising Its ugly head Little Black Rabbit 16 [see pages 8 & 9]. And yet a coherent and humane energy strategy Is staring us Copy date for next issue: in _the face. An energy conservation programme, If Initiated, would Immediately Friday, February 26th, 1982. create thousands of Jo~s, save our oil reserves and eliminate the need for expen sive and dangerous nuclear power stations; and give us the breathing space to HELP! develop an alternative energy strategy [see page 11]. The weather hasn't smiled on the Smi The Combined H.eat and Power feasibility study of Atklns and Partners is ex ling Sun Shop. -

PUSH Solent Energy Strategy

Future Solent and Partnership for Urban South Hampshire (PUSH) Solent Energy Strategy Final Report Issue 3 | 5 January 2015 This report takes into account the particular instructions and requirements of our client. It is not intended for and should not be relied upon by any third party and no responsibility is undertaken to any third party. Job number 232615-00 Ove Arup & Partners Ltd 63 St Thomas Street Bristol BS1 6JZ United Kingdom www.arup.com Document Verification Job title Solent Energy Strategy Job number 232615-00 Document title Final Report File reference Document ref Revision Date Filename Solent Energy Strategy 2014 Version.docx Draft 1 2 Jan Description First draft 2014 Prepared by Checked by Approved by Name Signature Issue 16 May Filename SOLENT ENERGY STRATEGY FINAL ISSUE 160514.docx 2014 Description Prepared by Checked by Approved by Name Michael Thompson Ann Cousins Wayne Dyer Signature Issue 2 29 Aug Filename SOLENT ENERGY STRATEGY August 2014 Final 2014 Description Prepared by Checked by Approved by Name Sophie England Ann Cousins Wayne Dyer Signature Issue 3 5 Jan Filename SOLENT ENERGY STRATEGY January 2015 Version.docx 2015 Description Updated to incorporate final comments Prepared by Checked by Approved by Name Ann Cousins Ann Cousins Wayne Dyer Signature Issue Document Verification with Document | Issue 3 | 5 January 2015 W:\PUSH\MEETINGS & EVENTS\1. PUSH MEETINGS\PUSH CHIEF EXEC MEETINGS\PUSH CX 2015\13.03.15\SOLENT ENERGY STRATEGY JANUARY 2015 VERSION WD PROOF V3 (2).DOCX Future Solent and Partnership for Urban South Hampshire (PUSH) Solent Energy Strategy Final Report Contents Page Executive Summary 1 Introduction 1 Energy in the Solent 1 Why an Energy Strategy? 1 Developing the Strategy 2 Meeting the energy diversification challenge. -

Proposed Southampton Biomass Plant, West Bay Road Lpa Ref: 12/00749/Preap1 Date of Decision: 24 July 2012 Report Of: Planning & Development Manager

DECISION-MAKER: PLANNING & RIGHTS OF WAY PANEL SUBJECT: PROPOSED SOUTHAMPTON BIOMASS PLANT, WEST BAY ROAD LPA REF: 12/00749/PREAP1 DATE OF DECISION: 24 JULY 2012 REPORT OF: PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT MANAGER STATEMENT OF CONFIDENTIALITY N/A BRIEF SUMMARY The City Council was consulted last year for its views on a proposed biomass power plant in Western Docks of the Port of Southampton. Before the Council made its formal comment ‘the promoter’ of the scheme, Helius Energy plc, released a press statement confirming that the scheme was to be reviewed. The City Council has been formally consulted again by Helius Energy plc regarding its revised proposals for a 100 Megawatt biomass fuelled electricity generating station (with the capability to provide heat) in a revised location on land in the Western Docks. A site location plan is attached at Appendix 1. The key changes to the proposals are: • The site location has been changed to achieve a greater separation between the power plant and the nearest residential property (from 125 to 250 metres); • The form of the buildings has been amended and three different architectural approaches have been submitted for public comment; • The building heights have been reduced (by between 5-10 metres) for the majority of the buildings with the location of the main boiler house changed; • The option of using hybrid cooling towers has been discounted removing the potential for water vapour plumes from the cooling assembly; The project is designated as a Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project (NSIP) for the purposes of planning control and will not be determined by the Council. -

POWERING CHANGE Preliminary Results for the Year to 31 March 2021

POWERING CHANGE Preliminary Results for the year to 31 March 2021 Disclaimer This financial report contains forward-looking statements about financial and operational matters. Because they relate to future events and are subject to future circumstances, these forward-looking statements are subject to risks, uncertainties and other factors. As a result, actual financial results, operational performance and other future developments could differ materially from those envisaged by the forward-looking statements. SSE plc gives no express or implied warranty as to the impartiality, accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information, opinions or statements expressed herein. Neither SSE plc nor its affiliates assume liability of any kind for any damage or loss arising from any use of this document or its contents. This document does not constitute an offer or invitation to underwrite, subscribe for, or otherwise acquire or dispose of any SSE shares or other securities and the information contained herein cannot be relied upon as a guide to future performance. Definitions These consolidated financial results for the year ended 31 March 2021 have been prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (‘IFRSs’) and its interpretations as issued by the International Accounting Standards Board (‘IASB’) and adopted by the European Union (‘adopted IFRS’). In order to present the financial results and performance of the Group in a consistent and meaningful way, SSE applies a number of adjusted accounting measures throughout this financial report. These adjusted measures are used for internal management reporting purposes and are believed to present the underlying performance of the Group in the most useful manner for ordinary shareholders and other stakeholders. -

SSE Annual Report 2009

Scottish and Southern Energy plc Annual Report 2009 Producing energy in a more sustainable way with new developments like the Glendoe hydro electric scheme. Helping make electricity and gas more affordable by offering a ‘better plan’ and installing insulation. Ensuring electricity supply is reliable through investing in networks in England and Scotland. Providing more capacity for the UK to maintain dependable supplies of gas through development at Aldbrough. SSE’s core purpose is to provide the energy people need in a reliable and sustainable way. Our Values Safety, service, efficiency, sustainability, excellence, teamwork – the SSE SET. Our Strategy To deliver sustained real growth in the dividend payable to shareholders through the efficient operation of, and investment in, a balanced range of regulated and non-regulated energy-related businesses. Our Team More than 18,500 people, working from power stations, depots, customer service centres, offices and shops. * Unless otherwise stated, this Annual Report describes adjusted operating profit before exceptional items, the impact of IAS 32 and IAS 39 and after the removal of taxation and interest on profits from jointly-controlled entities and associates. In addition, it describes adjusted profit before tax before exceptional items, the impact of IAS 32 and IAS 39 and after the removal of taxation on profits from jointly-controlled entities and associates. It also describes adjusted earnings and earnings per share before exceptional items, the impact of IAS 32 and IAS 39 and deferred -

Marchwood CCGT Power Station

PROJECT CASE STUDY IE28 BOLL FILTRATION SOLVES FISHY PROBLEM Marchwood CCGT Power Station Marchwood Power Station is a modern CCGT (combined cycle gas turbine) Power Station situated on the banks of the River Test overlooking the Port of Southampton. The 840 Mw Station, which supplies power to approximately one million homes in the Southampton area, uses cooling water taken from the River Test estuary at a rate of some 15 tonnes a second. The raw water is also used on-site as general wash water, including for the removal of debris, such as seaweed, from the condenser bandscreens. Marchwood Power Station When the Station was built, the water cooling line was fitted with a 1.6mm duplex filtration system. However, problems soon arose with blockages to the screen nozzles and the need for daily cleaning of filter baskets – caused by mussel lava and other organic matter entering the system. The spray sets and pipework to the screens were also corroded and blocked with the growing mussels. A BOLLFILTER system was fitted with three 6.18.2 heavy duty automatic backflushing filters providing constant filtration to 500 microns, plus the original duplex filters as standby. Each automatic filter has a 3mm rubber lining and special profile filter elements with Marchwood Power Station Bandscreen hydrodynamic backflush boost to further prevent build-up of organic matter. James Brown, Marchwood Mechanical Engineer, who was responsible for designing the pipework for the new filtration system explains the advantages of the automatic filters. “When the site started operating, we soon realised the problems caused by inadequate filtration. -

Colour Guide

Colour Guide Notice of Gas Transmission Transportation Charges Effective from 1 April 2013 Introduction NTS Charges to Apply From 1 April 2013 This notice is issued in line with National Grid Gas’s (“National Grid”) Transporters Licence in respect of the NTS and our obligations contained in the Uniform Network Code, which requires National Grid to provide at least two months notice of changes to its gas transportation charges. This notice details changes that will apply from 1 April 2013 and follows the ‘indicative notice’ published on 2 November 2012. This notice is split into four parts: • TO Charges • TO Entry Commodity • DN Pension Deficit • TO Exit Capacity • TO Exit Commodity • SO Charges • SO Entry and Exit Commodity • Other SO Charges • St Fergus Compression • Connected System Exit Points Administration • Supporting Information • Appendices Basis of preparing the charges / allowed revenues National Grid sets its charges to recover the price controlled allowances set by Ofgem. The current price control expires on 31 March 2013 and Ofgem has issued its Final Proposals for the RIIO-T1 price control to apply from 1 April 2013 1. National Grid has used Ofgem’s RIIO-T1 Final Proposals, which were published on 21 December 2012, as the basis for calculating the charges contained in this notice. 2 A summary of the revenues used to set the charges is given in Table 2 in Appendix 1. 1http://www.ofgem.gov.uk/Pages/MoreInformation.aspx?docid=342&refer=Networks/Trans/PriceControls/RIIO- T1/ConRes 2 Given the timing of setting charges, we have used the figures which result from Ofgem’s RIIO-T1 Final Proposals, however this should not be interpreted as acceptance of the Final Proposals by National Grid. -

Marchwood Power Limited the Installation Is: Marchwood Power Station This Variation Notice Number Is: EPR/BL6217IM/V010

Environment Agency Review of an Environmental Permit for an Installation subject to Chapter II of the Industrial Emissions Directive under the Environmental Permitting (England & Wales) Regulations 2016 Decision document recording our decision-making process following review of a permit The Permit number is: EPR/BL6217IM The Operator is: Marchwood Power Limited The Installation is: Marchwood Power Station This Variation Notice number is: EPR/BL6217IM/V010 What this document is about Article 21(3) of the Industrial Emissions Directive (IED) requires the Environment Agency to review conditions in permits that it has issued and to ensure that the permit delivers compliance with relevant standards, within four years of the publication of updated decisions on best available techniques (BAT) conclusions. We have reviewed the permit for this installation against the revised BAT Conclusions for large combustion plant published on 17th August 2017. This is our decision document, which explains the reasoning for the consolidated variation notice that we are issuing. It explains how we have reviewed and considered the techniques used by the Operator in the operation and control of the plant and activities of the installation. This review has been undertaken with reference to the decision made by the European Commission establishing best available techniques (BAT) conclusions (‘BAT Conclusions’) for large combustion plant as detailed in document reference IEDC-7-1. It is our record of our decision-making process and shows how we have taken into account all relevant factors in reaching our position. It also provides a justification for the inclusion of any specific conditions in the permit that are in addition to those included in our generic permit template. -

Cooling Water Options for the New Generation of Nuclear Power Stations in the UK

Cooling Water Options for the New Generation of Nuclear Power Stations in the UK SC070015/SR3 The Environment Agency is the leading public body protecting and improving the environment in England and Wales. It’s our job to make sure that air, land and water are looked after by everyone in today’s society, so that tomorrow’s generations inherit a cleaner, healthier world. Our work includes tackling flooding and pollution incidents, reducing industry’s impacts on the environment, cleaning up rivers, coastal waters and contaminated land, and improving wildlife habitats. This report is the result of research commissioned and funded by the Environment Agency. Published by: Author(s): Environment Agency, Rio House, Waterside Drive, Turnpenny, A.W.H., Coughlan, J., Ng, B., Crews, P., Aztec West, Almondsbury, Bristol, BS32 4UD Bamber, R.N., Rowles, P. Tel: 01454 624400 Fax: 01454 624409 www.environment-agency.gov.uk Dissemination Status: Released to all regions ISBN: 978-1-84911-192-8 Publicly available © Environment Agency June 2010 Keywords: Nuclear, cooling water, entrainment, impingement, All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced thermal with prior permission of the Environment Agency. Research Contractor: The views and statements expressed in this report are Jacobs Engineering Ltd those of the author alone. The views or statements Kenneth Dibben House expressed in this publication do not necessarily Enterprise Road represent the views of the Environment Agency and the Chilworth Science Park Environment Agency cannot accept any responsibility for Southampton such views or statements. SO16 7NS UK This report is printed on Cyclus Print, a 100% recycled stock, which is 100% post consumer waste and is totally Tel.: +44(0)2380 893 513 chlorine free.