Beach Buckets Lawrence Hall of Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biological Catalysis of the Hydrological Cycle: Life's Thermodynamic Function

Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss., 8, C1907–C1919, Hydrology and 2011 Earth System www.hydrol-earth-syst-sci-discuss.net/8/C1907/2011/ Sciences © Author(s) 2011. This work is distributed under Discussions the Creative Commons Attribute 3.0 License. Interactive comment on “Biological catalysis of the hydrological cycle: life’s thermodynamic function” by K. Michaelian K. Michaelian karo@fisica.unam.mx Received and published: 2 June 2011 Complete response to Prof. Schymanski: General Comments In a preliminary response to Prof. Schymanski and the anonymous referee (Michaelian, 2011a), I clarified that my paper neither invokes, nor requires, the “maximum entropy production principle”. The paper simply associates Onsager’s principle (1931) of the coupling of irreversible processes, and the associated increase in entropy production, with the evidence (e.g. Zotin, 1984) for an increase in the amount of coupling of irre- versible biotic processes over the history of life on Earth. The hypothesis of my paper C1907 is that biological irreversible processes also couple with abiotic irreversible processes, in particular, that biology catalyzes the hydrological cycle. This coupling augments the global entropy production of Earth in its solar environment, in accordance with Onsager’s principle. I also suggested in my preliminary response that the particular history of Earth with regard to entropy production would depend very much on par- ticular initial conditions (even microscopic), the kinetics (dependent on the particular forces) and subsequent external perturbations (even microscopic). This dependence arises because the Earth system under the solar photon flux is non-linear and out of equilibrium (Prigogine, 1972). Prof. Schymanski asks; 1) ”What is the mechanism that selects for biota that contribute more to planetary entropy production over such that contribute less but invest more e.g. -

The Importance of Ecological Memory for Trophic Rewilding As an Ecosystem Restoration Approach

Biol. Rev. (2019), 94,pp.1–15. 1 doi: 10.1111/brv.12432 The importance of ecological memory for trophic rewilding as an ecosystem restoration approach 1,2,4 1,3 1,2 Andreas H. Schweiger ∗ , Isabelle Boulangeat , Timo Conradi , Matt Davis1,4 and Jens-Christian Svenning1,4 1Section for Ecoinformatics and Biodiversity, Department of Bioscience, Aarhus University, Ny Munkegade 114, 8000, Aarhus C, Denmark 2Plant Ecology, Bayreuth Center for Ecology and Environmental Research (BayCEER), University of Bayreuth, 95440, Bayreuth, Germany 3University Grenoble Alpes, Irstea, UR LESSEM, 2 rue de la Papeterie-BP 76, F-38402, St-Martin-d’H`eres, France 4Center for Biodiversity Dynamics in a Changing World (BIOCHANGE), Aarhus University, Ny Munkegade 114, 8000, Aarhus C, Denmark ABSTRACT Increasing human pressure on strongly defaunated ecosystems is characteristic of the Anthropocene and calls for proactive restoration approaches that promote self-sustaining, functioning ecosystems. However, the suitability of novel restoration concepts such as trophic rewilding is still under discussion given fragmentary empirical data and limited theory development. Here, we develop a theoretical framework that integrates the concept of ‘ecological memory’ into trophic rewilding. The ecological memory of an ecosystem is defined as an ecosystem’s accumulated abiotic and biotic material and information legacies from past dynamics. By summarising existing knowledge about the ecological effects of megafauna extinction and rewilding across a large range of spatial and temporal scales, we identify two key drivers of ecosystem responses to trophic rewilding: (i) impact potential of (re)introduced megafauna, and (ii) ecological memory characterising the focal ecosystem. The impact potential of (re)introduced megafauna species can be estimated from species properties such as lifetime per capita engineering capacity, population density, home range size and niche overlap with resident species. -

8.01 the Early History of Life E

8.01 The Early History of Life E. G. Nisbet and C. M. R. Fowler Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham, UK 8.01.1 INTRODUCTION 2 8.01.1.1 Strangeness and Familiarity—The Youth of the Earth 2 8.01.1.2 Evidence in Rocks, Moon, Planets, and Meteorites—The Sources of Information 3 8.01.1.3 Reading the Palimpsests—Using Evidence from the Modern Earth and Biology to Reconstruct the Ancestors and their Home 3 8.01.1.4 Modeling—The Problem of Taking Fragments of Evidence and Rebuilding the Childhood of the Planet 3 8.01.1.5 What Does a Planet Need to be Habitable? 4 8.01.1.6 The Power of Biology: The Infinite Improbability Drive 4 8.01.2 THE HADEAN (,4.56–4.0 Ga AGO) 5 8.01.2.1 Definition of Hadean 5 8.01.2.2 Building a Habitable Planet 5 8.01.2.3 The Hadean Record 7 8.01.2.4 When and Where Did Life Start? 7 8.01.3 THE ARCHEAN (,4–2.5 Ga AGO) 8 8.01.3.1 Definition of Archean 8 8.01.3.2 The Archean Record 8 8.01.3.2.1 Greenland 8 8.01.3.2.2 Barberton 9 8.01.3.2.3 Western Australia 9 8.01.3.2.4 Steep Rock, Ontario, and Pongola, South Africa 10 8.01.3.2.5 Belingwe 11 8.01.4 THE FUNCTIONING OF THE EARTH SYSTEM IN THE ARCHEAN 11 8.01.4.1 The Physical State of the Archean Planet 11 8.01.4.2 The Surface Environment 13 8.01.5 LIFE: EARLY SETTING AND IMPACT ON THE ENVIRONMENT 14 8.01.5.1 Origin of Life 14 8.01.5.2 RNA World 15 8.01.5.3 The Last Common Ancestor 17 8.01.5.4 A Hyperthermophile Heritage? 19 8.01.5.5 Metabolic Strategies 21 8.01.6 THE EARLY BIOMES 21 8.01.6.1 Location of Early Biomes 21 8.01.6.2 Methanogenesis: Impact on the Environment 22 -

The Evolutionary Impact of Invasive Species

Colloquium The evolutionary impact of invasive species H. A. Mooney* and E. E. Cleland Department of Biological Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305-5020 Since the Age of Exploration began, there has been a drastic and biotic environments that exist now are quite different from breaching of biogeographic barriers that previously had isolated those that have existed in recent geological times. the continental biotas for millions of years. We explore the International commerce has facilitated the movement of nature of these recent biotic exchanges and their consequences species; this is true globally and across taxonomic groups. on evolutionary processes. The direct evidence of evolutionary Ironically, this has increased species richness in many places consequences of the biotic rearrangements is of variable quality, where new species are introduced. The actual numbers of but the results of trajectories are becoming clear as the number individuals and species being transported across biogeographical of studies increases. There are examples of invasive species barriers every day is presumably enormous. However, only a altering the evolutionary pathway of native species by compet- small fraction of those transported species become established, itive exclusion, niche displacement, hybridization, introgression, and of these generally only about 1% become pests (5). Over predation, and ultimately extinction. Invaders themselves time however, these additions have become substantial. There evolve in response to their interactions with natives, as well as are now as many alien established plant species in New Zealand in response to the new abiotic environment. Flexibility in be- as there are native species. Many countries have 20% or more havior, and mutualistic interactions, can aid in the success of alien species in their floras (6). -

New RNA Research Demonstrates Prebiotic Possibility

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Chemistry Faculty Publications Chemistry Department 1-2020 New RNA Research Demonstrates Prebiotic Possibility David W. Ball Cleveland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/scichem_facpub Part of the Chemistry Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Publisher's Statement Link to publisher version: https://skepticalinquirer.org/2020/01/new-rna-research-demonstrates- prebiotic-possibility/ Recommended Citation Ball, David W., "New RNA Research Demonstrates Prebiotic Possibility" (2020). Chemistry Faculty Publications. 522. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/scichem_facpub/522 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Chemistry Department at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chemistry Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. New RNA Research Demonstrates Prebiotic Possibility David W. Ball Creationists and other religious fundamentalists commonly (and erroneously) bring up the issue of abiogenesis as an argument against evolution, claiming that life is too complex to have arisen naturally from simple (non-living) chemicals. Abiogenesis is the development of chemical life from non-living chemicals, and is an active area of research for scientists studying the “Origin Of Life” question. The issue is largely irrelevant as an argument against evolution because evolution deals with what happens after life is formed. It is widely accepted that modern abiogenesis research traces back to the Miller-Urey experiment, performed by Stanley Miller at the University of Chicago (with assistance from Harold Urey) and published in 1953. -

An Evolving Astrobiology Glossary

Bioastronomy 2007: Molecules, Microbes, and Extraterrestrial Life ASP Conference Series, Vol. 420, 2009 K. J. Meech, J. V. Keane, M. J. Mumma, J. L. Siefert, and D. J. Werthimer, eds. An Evolving Astrobiology Glossary K. J. Meech1 and W. W. Dolci2 1Institute for Astronomy, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822 2NASA Astrobiology Institute, NASA Ames Research Center, MS 247-6, Moffett Field, CA 94035 Abstract. One of the resources that evolved from the Bioastronomy 2007 meeting was an online interdisciplinary glossary of terms that might not be uni- versally familiar to researchers in all sub-disciplines feeding into astrobiology. In order to facilitate comprehension of the presentations during the meeting, a database driven web tool for online glossary definitions was developed and participants were invited to contribute prior to the meeting. The glossary was downloaded and included in the conference registration materials for use at the meeting. The glossary web tool is has now been delivered to the NASA Astro- biology Institute so that it can continue to grow as an evolving resource for the astrobiology community. 1. Introduction Interdisciplinary research does not come about simply by facilitating occasions for scientists of various disciplines to come together at meetings, or work in close proximity. Interdisciplinarity is achieved when the total of the research expe- rience is greater than the sum of its parts, when new research insights evolve because of questions that are driven by new perspectives. Interdisciplinary re- search foci often attack broad, paradigm-changing questions that can only be answered with the combined approaches from a number of disciplines. -

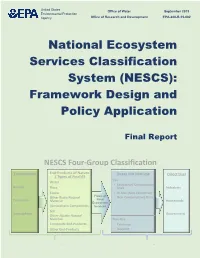

National Ecosystem Services Classification System (NESCS): Framework Design and Policy Application

United States Office of Water September 2015 Environmental Protection Agency Office of Research and Development EPA-800-R-15-002 National Ecosystem Services Classification System (NESCS): Framework Design and Policy Application Final Report NESCS Four-Group Classification Environment End-Products of Nature Direct Use Non-Use Direct User Structure / Types of Final ES Use Water • Extractive/ Consumptive Aquatic Flora Uses Industries Fauna • In-Situ (Non-Extractive/ Flows of Non-Consumptive) Uses Other Biotic Natural Final Terrestrial Material Households Ecosystem Atmospheric Components Services Soil Atmospheric Government Other Abiotic Natural Material Non-Use Composite End-Products • Existence Other End-Products • Bequest (Supply) (Demand) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors thank Jennifer Richkus, Jennifer Phelan, Robert Truesdale, Mary Barber, David Bellard, and others from RTI International for providing feedback and research support during the development of this report. The early leadership of former EPA employee John Powers proved instrumental in launching this effort. The authors thank Amanda Nahlik, Tony Olsen, Kevin Summers, Kathryn Saterson, Randy Bruins, Christine Davis, Bryan Hubbell, Julie Hewitt, Ashley Allen, Todd Doley, Karen Milam, David Simpson, and others at EPA for their discussion and feedback on earlier versions of this document. In addition, the authors thank V. Kerry Smith, Neville D. Crossman, and Brendan Fisher for review comments. Finally, the authors would like to thank participants of the two NESCS Workshops held in 2012 and 2013, as well as participants of an ACES session in 2014. Any factual or attribution errors are the responsibility of the authors alone. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION This document was developed under U.S. EPA Contract EP-W-11-029 with RTI International (Paramita Sinha and George Van Houtven), in collaboration with the ORISE Participant Program between U.S. -

Earth As an Alien World

Earth as an alien world Enric Pallé Kavli Institute of Theoretical Physics Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias Exoplanets Rising Conference – May 2010 A short history of Earth observations World Map by Eratosthenes, 194 B.C. World Map by Martin Waldseemüller, 1507 Earth curvature, V2 rocket 1946 Small rocket picture 1904 Apollo VIII, 1969 1967, First Color Picture, ATS-3, 37,000 km Nowadays we can monitor night lights, atmospheric changes, plankton blooms, forest health, etc... 10 Year advance > Planet detection 51 % rational thinking > Characterization But, how does our planet look like to ET? When observing an exoplanet, all the light will come from a single point. Different seasons, phase, geometry and weather Age Wavelength Observing the Earth as a planet (no spatial resolution) Earth–as-a-point observations with a very remote sensor A compilation of high spatial resolution data into a global spectra or photometry, and modeling Earthshine Observations: The Earthshine is the ghostly glow on the dark side of the Moon Earth observations from remote platforms The Earthshine on the moon ES/MS = albedo (+ geometry and moon properties) Leonardo da Vinci, Codex Leicester, 1510 North America Cloudy Asia Dark Pacific Dark Atlantic Global cloud data allow us a precise modeling of the earthshine- contributing area during our observations Palle et al, JGR, 2003 The Earth clouds: A unique feature in the solar system? Even with the presence of clouds, there are clear daily and yearly photometric patterns with relatively large amplitude Ocean Glint • Water • Smooth Ice • Thin clouds • Ethane Williams & Gaidos, Icarus, 2008 Earthshine observations do not get us there and remote observations are missing MESSENGER, 2005 VIRTIS @ ROSETTA, 250,000 km from Earth Variability in the IR is more muted than in the visible and strongly dependent con weather conditions. -

Optimisation of Alkali Separation in Thermal Battery Recycling

When carbon is not enough: Comprehensive Ecological Rucksack Indicators for Products 1 1 1 2 Eva Burger , Friedrich Hinterberger , Stefan Giljum , Christopher Manstein 1 Sustainable Europe Research Institute (SERI), Vienna, Austria 2 Factor 10 Institute, Vienna, Austria Corresponding author: Eva Burger [email protected] Paper presented at R‘09 Twin World Congress in Davos. Comments are very welcome. Abstract Consumers increasingly demand more transparent information about the sustainability performance of products and services. Thus companies aim at measuring and communicating the environmental performance of products. But which indicators enable a consistent measurement of the environmental sustainability of a product? Some major European initiatives have been launched, focusing in most cases on the indicator Carbon Footprint. But the Carbon Footprint does not take into account resource scarcity and trade- offs between different environmental categories, including the use of raw materials, water and land. In this paper, we present a pilot study assessing a more comprehensive set of indicators, which was conducted in 2008 with a number of Austrian companies. In contrast to the single indicator approach, a set of five indicators was selected and tested for the assessment of the environmental sustainability performance of products: Abiotic Material Rucksack, Biotic Material Rucksack, Water Rucksack, Actual Land Use and Carbon Footprint. In an ongoing Austrian research project, we currently explore, whether this indicator set can be further developed into an integrated and Web-based Business Resource Intensity Index (BRIX). Keywords: Carbon Footprint, MIPS, resource efficiency, sustainable production 1 Introduction Many of today‘s most urgent environmental problems arise from ever increasing volumes of worldwide production and consumption and the associated resource flows (UNEP, 2007). -

Astronomy Meets Biology: EFOSC2 and the Chirality of Life

Astronomical Science Astronomy Meets Biology: EFOSC2 and the Chirality of Life Michael Sterzik1 molecule are called enantiomers, and the extreme environment on Earth, and the Stefano Bagnulo 2 two forms are generally referred to as microbial colonisation of subsurface lay Armando Azua 3 righthanded and lefthanded, or dextro ers in halites (rock salt) and quartz rocks Fabiola Salinas 4 rotatory and levorotatory. by specific cyanobacteria. In the most Jorge Alfaro 4 hostile environments (exceptional aridity, Rafael Vicuna 3 The term homochirality is used when a salinity, and extreme temperatures), a molecule (or a crystal) may potentially primitive type of cyanobateria, Chroococ- exist in both forms, but only one is actu cidiopsis, can be the sole surviving 1 ESO ally present. Homochirality character organism. This has interesting implications 2 Armagh Observatory, United Kingdom ises life as we know it: all living material for the potential habitability, and eventual 3 Department of Molecular Genetics and on Earth contains and synthesises sugars terraforming, of certain areas on Mars Microbiology, Pontificia Universidad and nucleic acids exclusively in their (Friedmann & Ocampo-Friedmann, 1995). Católica de Chile, Chile righthanded form, while amino acids and 4 Faculty of Physics, Pontificia Universi proteins occur only in their lefthanded The idea of using the ESO Faint Object dad Católica de Chile, Chile representation. However, in all these Spectrograph and Camera (EFOSC2) cases, both enantiomers are chemically to investigate samples of Chroococcidi- possible and energetically equal. The opsis extracted from the underside of Homochirality, i.e., the exclusive use of reasons for homochirality in living mate Atacama Desert quartzes and to measure L-amino acids and D-sugar in biologi- rial are unknown, but they must be their circular polarisation in a laboratory cal material, induces circular polarisa- related to the origin of life. -

Returned Astrobiology Sample Mission Architectures

2003-01-2675 Global Overview: Returned Astrobiology Sample Mission Architectures Marc M. Cohen NASA-Ames Research Center ABSTRACT return missions -- while based upon some internationally agreed standards – are occurring mainly on a case-by- This paper presents a global overview of current, case basis. This basis includes two fundamental planned and proposed sample missions. At present, choices: unrestricted return or restricted return. missions are in progress to return samples from asteroids, comets and the interstellar medium. More Unrestricted return refers to missions in which the space missions are planned to Mars and the asteroids. Future agencies deem the probability of finding biotic material to sample return missions include more targets including be negligible. The constraints upon an unrestricted Europa, Mercury and Venus. This review identifies the return are relatively lenient, and concern mainly the need for developing a coordinated international system ordinary safe and secure recovery of the spacecraft for the handling and safety certification of returned without any special biohazard protection. samples. Such a system will provide added assurance to the public that all the participants in this new Restricted return refers to missions in which the space exploration arena have thought through the technical agencies deem the probability of finding biotic material to challenges and reached agreement on how to proceed. be non-negligible, although perhaps still extremely small. In contrast, any mission that may return biotic material All these future returned sample missions hold relevance by definition shall be a restricted return. A restricted to the NASA Astrobiology program because of the return would require extraordinary measures above and potential to shed light on the origins of life, or even to beyond those of an unrestricted return, including return samples of biological interest. -

Comments on the Contending Hypotheses About the Origin of Life

Comments on the contending hypotheses about the origin of life Inês Fernandes1, Miguel Amaral2, Orfeu Bertolami2 (email: [email protected]) 1Departamento de Biologia,2Departamento de Física e Astronomia, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade do Porto The problem on the origin of life is one of the most challenging and fascinating of the whole science. Understanding how living organisms have arisen from the abiotic conditions believed to prevail in most of the Universe is a formidable and exciting enigma. A great deal of effort has been devoted to concoct a plausible chain of events to explain how, from the abiotic conditions of the primitive Earth, the basic building organic molecules could arise, a proposal often referred to as Oparin-Haldane hypothesis, and whose plausibility has been partially shown by the Miller-Urey experiment. Furthermore, thanks to the understanding of DNA’s structure and the genetic code we can map out the history of evolution all the way back to single celled life. However, this brings a problem as the DNA is a quite efficient way to store information, but cells to function rely on other molecules, proteins, to replicate, grow and survive. Proteins, on their hand, are efficient molecular machines to keep cells alive and healthy, but they are unable to store information or to make copies of themselves as for that they require the DNA. Thus, DNA needs proteins to function, and proteins need DNA to exist. So, which came first? Which molecule made life possible? Scientists have proposed various scenarios about the primeval set of biomolecules. In fact, there is a third type of molecule that may hold the answer: RNA.