Chinese Ceos: Are Their Managing Philosophy and Practices Influenced by the Western Managerial Principles?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China Motor Corporation Investor Conference (Ticker Symbol :2204)

China Motor Corporation Investor Conference (ticker symbol :2204) Aug. 19, 2020 0 Agenda 14:30 China Motor Corporation Investor Conference CMC Operating Results and Future Plan 8 Opinion Exchange 15:10 Presenter :Cheng-Chang Huang Vice President 1 CMC Operating Results and Future Plan (ticker symbol :2204) Safe Harbor Notice This presentation contains forward-looking statements concerning the financial condition, results of operations and businesses of China Motor Corporation (“CMC”). All statements other than statements of historical fact are, or may be deemed to be, forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements are subject to significant risks and uncertainties which may vary from time to time and actual results may differ materially from those contained in the forward-looking statements, whether as result of new information, future events, or otherwise. CMC, its subsidiaries and representatives do not undertake any obligation to the damages resulted from the use, with or without negligence, of this presentation or other information related with it, except as required by law. Any part of this presentation can not be, on any purpose, directly or indirectly replicated, spread, transmitted or published. 3 Outline Market Overview • Auto Market in Taiwan • Auto Market in China CMC’s Operating Results in the first half of 2020 CMC’s Prospect in 2020 4 Auto Market in Taiwan Estimated (Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics) (Taiwna Institute of (Chung-Hua Institution Economic Research) Economic Research) (Source: Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics) Due to the COVID-19, the economic growth rate is a negative value in Q2. But the epidemic outbreak has been controlled, the government deregulate gradually and introduce consumption policies to boost consumption in the second half of the year. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2012 Contents

CHINA METAL INTERNATIONAL HOLDINGS INC. (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) Stock Code : 319 ANNUAL REPORT 2012 CONTENTS 2 CORPORATE INFORMATION 3 CHAIrman’s STATEMENT 5 MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS 8 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT 17 REPORT OF THE DIRECTORS 25 BIOGRAPHICAL DETAILS OF DIRECTORS AND SENIOR MANAGEMENT 31 INDEPENDENT AUDITor’s REPORT 32 CONSOLIDATED INCOME STATEMENT 33 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF COMPREHENSIVE INCOME 34 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION 35 STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION 36 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN EQUITY 37 CONSOLIDATED CASH FLOW STATEMENT 38 NOTES TO THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 86 FIVE YEARS SUMMARY Annual Report 2012 CHINA METAL INTERNATIONAL HOLDINGS INC 1 CORPORATE INFORMATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS PLACE OF BUSINESS IN HONG KONG Executive Directors Room 1502, 15th Floor The Chinese Bank Building KING Fong-Tien (Chairman) 61-65 Des Voeux Road Central TSAO Ming-Hong (Vice Chairman) Hong Kong WU Cheng-Tao CHEN Shun Min PRINCIPAL SHARE REGISTRAR AND TRANSFER OFFICE Non-Executive Director Appleby Corporate Services (Cayman) Ltd. Christian Odgaard PEDERSEN Clifton House 75 Fort Street Independent Non-Executive Directors P.O. Box 1350 GT George Town, Grand Cayman WONG Tin Yau, Kelvin, FHKIoD Cayman Islands CHIU LIN Mei-Yu (also known as Mary Lin Chiu) CHEN Pou-Tsang (also known as Angus P.T. Chen) HONG KONG BRANCH SHARE REGISTRAR COMPANY SECRETARY AND TRANSFER OFFICE TSE Kam Fai Computershare Hong Kong Investor Services Limited Shops 1712-1716, 17/F AUTHORISED REPRESENTATIVES Hopewell Centre 183 Queen’s Road East CHEN Shun Min Wanchai, Hong Kong TSE Kam Fai PRINCIPAL BANKERS AUDIT COMMITTEE Agricultural Bank of China WONG Tin Yau, Kelvin, FHKIoD (chairman) Tianjin TEDA Branch CHIU LIN Mei-Yu (also known as Mary Lin Chiu) International Development Building CHEN Pou-Tsang (also known as Angus P.T. -

Encouraging Knowledge-Intensive Industries: What Australia Can Draw from the Industrial Upgrading Experiences of Taiwan and Singapore

ENCOURAGING KNOWLEDGE-INTENSIVE INDUSTRIES: WHAT AUSTRALIA CAN DRAW FROM THE INDUSTRIAL UPGRADING EXPERIENCES OF TAIWAN AND SINGAPORE John A. Mathews Macquarie Graduate School of Management Report commissioned by the Australian Business Foundation August 1999 CONTENTS Page Foreword 3 Executive Summary 5 Abbreviations 9 1. Introduction: What is there to learn from Asia in 1999? 11 2. Industrial upgrading in Taiwan 15 3. Case study: Taiwan's innovation alliances 35 4. Industrial upgrading in Singapore 57 5. Case study: Singapore's cluster development strategies 76 6. Common institutional elements: Industrial upgrading and institutional learning 83 7. Concluding remarks: A way forward for Australian firms and institutions 94 2 FOREWORD Professor John A. Mathews of the Macquarie Graduate School of Management was commissioned by the Australian Business Foundation to research and prepare a paper that would offer some practical examples of industrial upgrading of relevance for Australia. The paper submitted describes and analyzes the industrial and technological upgrading practices of firms and public institutions in Singapore and Taiwan. These two nations are of particular interest because they have weathered the recent Asian financial crisis well. Their institutional strategies are robust and have important lessons for other countries, including Australia. The Australian Business Foundation is Australia's newest, independent, private sector economic and industry policy think-tank. It is sponsored as a separate research arm by Australian Business, the pre-eminent business services organisation. The mission of the Australian Business Foundation is to strengthen Australian enterprise through research and policy innovation. It does this by conducting ground-breaking research, which it uses to foster informed and well-argued debates and imaginative policy solutions and initiatives. -

China Motor Corporation and Subsidiaries

China Motor Corporation and Subsidiaries Consolidated Financial Statements for the Nine Months Ended September 30, 2019 and 2018 and Independent Auditors’ Review Report INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REVIEW REPORT The Board of Directors and the Shareholders China Motor Corporation Introduction We have reviewed the accompanying consolidated balance sheets of China Motor Corporation and its subsidiaries (collectively, the “Group”) as of September 30, 2019 and 2018, the related consolidated statements of comprehensive income for the three months ended September 30, 2019 and 2018 and for the nine months ended September 30, 2019 and 2018, the consolidated statements of changes in equity and cash flows for the nine months then ended and the related notes to the consolidated financial statements, including a summary of significant accounting policies (collectively referred to as the “consolidated financial statements”). Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of the consolidated financial statements in accordance with the Regulations Governing the Preparation of Financial Reports by Securities Issuers and International Accounting Standard 34 “Interim Financial Reporting” endorsed and issued into effect by the Financial Supervisory Commission of the Republic of China. Our responsibility is to express a conclusion on the consolidated financial statements based on our reviews. Scope of Review Except as explained in the following paragraph, we conducted our reviews in accordance with Statement of Auditing Standards No. 65 “Review of Financial Information Performed by the Independent Auditor of the Entity”. A review of consolidated financial statements consists of making inquiries, primarily of persons responsible for financial and accounting matters, and applying analytical and other review procedures. A review is substantially less in scope than an audit and consequently does not enable us to obtain assurance that we would become aware of all significant matters that might be identified in an audit. -

China Motor Corporation 2020 Annual Report (Translation)

Stock Code:2204 China Motor Corporation 2020 Annual Report (Translation) Printed on March 31, 2021 Notice to Readers The Annual Report have been translated into English from the original Chinese version. If there is any conflict between the English version and the original Chinese version or any difference in the interpretation of the two versions, the Chinese version shall prevail. I. Information regarding Spokesperson, Deputy Spokesperson Spokesperson: Cheng-Chang Huang Title: Vice President Deputy Spokesperson: Yu-Chun Su Title: General Manager, Corporate Planning Division, China Motor Corporation Tel: 886-3-4783191 Email: [email protected] II. Contact Information of Headquarter, Branch Company and Plant Headquarter Address: 11F., No.2, Sec. 2, Dunhua S. Rd., Da’an Dist., Taipei City 106, Taiwan Tel: 886-2-23250000 Yang Mei Plant Address: No.618, Xiucai Rd., Yangmei Dist.,Taoyuan City 326, Taiwan Tel: 886-3-4783191 Hsin Chu Plant Address: No.2, Guangfu Rd., Hukou Township, Hsinchu County 303, Taiwan Tel: 886-3-5985841 III. Common Share Transfer Agent and Registrar Company: China Motor Corporation Address: 7F., No.150, Sec. 2, Nanjing E. Rd., Zhongshan Dist., Taipei City 104, Taiwan Tel: 886-2-25156421 Website: http:// www.china-motor.com.tw IV. Information regarding 2020 Auditors Company: Deloitte & Touche Auditors: Eddie Shao, Ya-Ling Wong Address: 20F, Taipei Nan Shan Plaza, No. 100, Songren Rd., Xinyi Dist., Taipei 11073, Taiwan Tel: 886-2-27259988 Website: http://www.deloitte.com.tw V. Information regarding Depositary: N.A. VI. Corporation Website: http:// www.china-motor.com.tw Table of Contents Report to Shareholders ________________________________________________ 6 Company Overview __________________________________________________ 8 I. -

China Motor Corporation 2021/Q1 Investor Conference (Ticker Symbol:2204)

China Motor Corporation 2021/Q1 Investor Conference (ticker symbol:2204) May. 26, 2021 1 Agenda 15:10 China Motor Corporation • Postponement of annual Investor Conference general meeting • 2021/Q1 Investor Conference 5 Opinion Exchange 15:50 Presenter:Cheng-Chang Huang Vice President 2 Safe Harbor Notice This presentation contains forward-looking statements concerning the financial condition, results of operations and businesses of China Motor Corporation (“CMC”). All statements other than statements of historical fact are, or may be deemed to be, forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements are subjects to significant risks and uncertainies which may vary from time to time and actual results may differ materially from those contained in the forward-looking statements, whether as result of new information, future events, or otherwise. CMC, its subsidiaries and representatives do not undertake any obligation to the damages resulted from the use, with or without negligence, of this presentation or other information related with it, except as required by law. Any part of this presentation can not be, on any purpose, directly or indirectly replicated, spread, transmitted or published. 3 Postponement of Annual General Meeting • For the purpose of COVID-19 epidemic prevention, the Financial Supervisory Commission postpones annual general meetings of all listed companies to 7/1-8/31. CMC will convene interim board meeting to schedule the annual general meeting. 4 Outline CMC's Sales Performance from Jan. to Apr. and Operating Results in 2021/Q1 1.2021 1~4 Sales Performance 2.2021/Q1 Financial Statements CMC's Prospect in 2021/Q2 1.CMC’s Prospect in 2021/Q2 2.Launch Two New Energy Vehicles 3.Corporate Governance Evaluation: Top 5% of listed companies for 7 years 5 CMC's Sales Performance from Jan. -

Taipei, Taiwan

19th October 8-10, 2013 Taipei, Taiwan Working together, achieving great things When your company and ours combine energies, great things can happen. SUCCESS TOGETHER You bring ideas, challenges and opportunities. We’ll bring powerful additive and market expertise, unmatched testing capabilities, integrated global supply and an independent approach to help you SUCCESS differentiate and succeed. TOGETHER Visit www.lubrizol.com/successtogether to experience Success Together. PRELIMINARY PROGRAM © 2013 The Lubrizol Corporation. All rights reserved. 130004 Table of Contents 2 PROGRAM AT-A-GLANCE 3 INTRODUCTION OF SETC 2013 4 COMMITTEE MEMBERS 7 CONFERENCE REGISTRATION 10 CONFERENCE VENUE 11 KEYNOTE SPEECH 14 PLENARY SESSION 18 EXHIBITION & POSTER SESSION WITH COFFEE BREAK, LUNCH SERVICE 19 SPECIAL EVENTS 20 SPONSORS 21 TECHNICAL VISITS 23 TECHNICAL SESSIONS 36 TRAVEL INFORMATION 37 TAIPEI INFORMATION 40 ACCOMMODATION 41 HOTEL MAP 42 ADVERTISEMENTS 56 TAIPEI METRO MAP 57 FLOOR PLAN Acknowledgements: PROGRAM AT-A-GLANCE October 7, 2013 October 8, 2013 October 9, 2013 October 10, 2013 Time\Date Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday 08:00-09:00 Opening Ceremony 09:00-10:00 & Keynote Speech Technical Sessions Technical Sessions (Room 201BCDE, 2F) (Room 201A, 201B, 201C, (Room 201A, 201B, 201C, Registration 10:00-11:00 201D, 201E, 201F, 2F) 201D, 201E, 201F, 2F) Technical Sessions 11:00-12:00 (Room 102, 103, 105, 1F; Exhibition 201A, 201F, 201BCDE, 2F) Technical Visits Lunch Lunch 12:00-13:00 (Banquet Hall, 3F) (Banquet Hall, 3F) Closing Ceremony & Registration Registration Lunch 13:00-14:00 (Banquet Hall, 3F) Technical Sessions (Room 201A, 201B, 201C, Exhibition Exhibition 201D, 201E, 201F, 2F) 14:00-15:00 Technical Sessions (Room 201A, 201B, 201C, 15:00-16:00 201D, 201E, 201F, 2F) Plenary Session 16:00-17:00 (Room 102, 1F) Registration 17:00-18:00 18:00-19:00 Welcome Reception (33F, TWTC) 19:00-20:00 Banquet (VIP Room, 4F) 20:00-21:00 • Registration: Lobby, 1F • TWTC: Taipei World Trade Center (See page 19) Note) Room and time are subject to change in the final program. -

2013 Taipei, Taiwan

19th Small Engine Technology Conference October 8-10, 2013 Taipei, Taiwan FINAL PROGRAM Table of Contents 2 PROGRAM AT-A-GLANCE 3 INTRODUCTION OF SETC2013 4 CONFERENCE INFORMATION 5 COMMITTEE MEMBERS 8 OPENING CEREMONY 12 KEYNOTE SPEECH 15 PLENARY SESSION 19 EXHIBITION & POSTER SESSION 22 SPECIAL EVENTS 23 LUNCH, AWARD AND CLOSING CEREMONY 24 TECHNICAL VISITS 26 SESSION TIMETABLE 29 ABSTRACT OF TECHNICAL SESSION 67 SETC2014 CALL FOR PAPERS 68 SPONSORS 69 TAIPEI INFORMATION 72 TAIPEI METRO MAP 73 FLOOR PLAN 79 ADVERTISEMENTS PROGRAM AT-A-GLANCE October 7, 2013 October 8, 2013 October 9, 2013 October 10, 2013 Time\Date Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday 08:00-09:00 Technical Sessions Technical Sessions 08:30-10:00 08:30-10:00 (Room 201A, 201B, 201C, (Room 201A, 201B, 201C, Opening Ceremony 09:00-10:00 201D, 201E, 2F) 201D, 201E, 2F) & Keynote Speech 08:00-11:30 on on 09:00-10:30 ti (Room 201BCDE, 2F) Coffee Break, Brief Coffee Break, Brief Presentation of Poster Presentation of Poster Session 10:00-10:30 Session 10:00-10:30 Registra 10:00-11:00 Coffee Break 10:30-11:00 Technical Sessions Technical Sessions 10:00-12:00 10:30-12:00 10:30-12:00 on Technical Sessions ti (Room 201A, 201B, 201C, (Room 201A, 201B, 201C, 11:00-12:00 11:00-12:00 201D, 201E, 2F) 201D, 201E, 2F) (Room 102, 103, 1F; Exhibi 201A, 201F, 2F) Technical Visits 08:00-16:30 08:00-17:00 12:00-13:00 08:00-17:00 on on Lunch on Lunch ti 12:00-13:30 ti 12:00-13:30 Lunch, Award & (Banquet Hall, 3F) (Banquet Hall, 3F) Closing Ceremony 12:00-14:00 Registra Registra (Banquet Hall, 3F) -

Trends in Overseas Direct Investment by Chinese Companies in 2013

Trends in Overseas Direct Investment by Chinese Companies in 2013 January 2015 China and North Asia Division Overseas Research Department Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) Exclusion of liability clause Responsibility for decisions made based on the information provided in this report shall rest solely on readers. Though JETRO strives to provide accurate information, JETRO will not be responsible for any loss or damage incurred by readers through the use of the information. Unauthorized reproduction prohibited Introduction There is a trend among Chinese companies toward direct foreign investment (FDI) that is becoming more active each year. China’s 2013 FDI (net, flow) announced in September 2014 set a new record, at USD107, 843.71 million, a 22.8% increase year-on-year. By region, Chinese FDI in Asia and Central and South America drove the increase, while FDI in Europe declined. By industry, mining and finance stood out as contributing to the increase, while manufacturing made a negative contribution. In light of these circumstances, this report presents multifaceted verification of the situation in regions of China with regard to Chinese FDI and the situation in the countries and regions that receive FDI, and it describes the current state of overseas development by Chinese companies, which are expanding around the world. This report appeared in JETRO Daily in November and December 2014, and it is based on the data available at the time of writing (September-October 2014).It is hoped that this report will serve as a reference in various quarters, including at Japanese companies. January 2015 Overseas Research Department, Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) . -

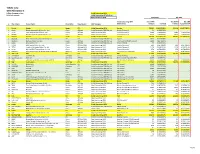

OEM PSAN Inflator Sales Data Schedule

Takata Corp OEM Allocation % Inflator shipping volume Initial Consenting OEM Units in thousands Initial Consenting OEM Roll-up Non-Consenting OEM Shipments ALL OEM Initial Consenting OEM Total PSAN Total PSAN ALL OEM # Short Name Formal Name Head office Classification OEM Category Relationship Inflators % of total Inflators ALLOCATION % 1 Honda Honda Japan CG Initial Consenting OEM Honda 53,397 14.8215192% 53,419 14.8277907% 2 CHAC Honda Automobile (China) Co., Ltd. China Affiliate Initial Consenting OEM Roll-up Honda Chinese JV 23 0.0062715% - - 3 GHAC GAC Honda Automobile Co., Ltd. China Affiliate Non-Consenting OEM Honda Chinese JV 3,682 1.0220562% 3,682 1.0220562% 4 WDHAC Dongfeng Honda Automobile Co., Ltd. China Affiliate Non-Consenting OEM Honda Chinese JV 4,323 1.2000105% 4,323 1.2000105% 5 Toyota Toyota Japan CG Initial Consenting OEM Toyota 44,018 12.2181997% 48,881 13.5681391% 6 NUMMI New United Motor Manufacturing, Inc. US CG Initial Consenting OEM Roll-up Toyota 1,922 0.5335676% - - 7 Daihatsu Daihatsu Motor Co., Ltd. Japan Affiliate Initial Consenting OEM Roll-up Toyota owned (100% owned) 2,908 0.8072901% - - 8 HINO Hino Motors, Ltd. Japan Affiliate Initial Consenting OEM Roll-up Toyota affiliate 33 0.0090817% - - 9 GTMC GAC Toyota Motor Co., Ltd. China Affiliate (KSS) Non-Consenting OEM Toyota Chinese JV 602 0.1671380% 602 0.1671380% 10 TFTM Tianjin FAW Toyota Motor Co., Ltd. China Affiliate (KSS) Non-Consenting OEM Toyota Chinese JV 3,128 0.8683364% 3,128 0.8683364% 11 SFTM Sichuan FAW Toyota Motor Co., Ltd. -

YULON Annual Report 2018

Annual Report 2018 Printed on April 30, 2019 SEC:mops.twse.com.tw YULON official Website:www.yulon-motor.com.tw Stock Code: 2201 I. Name, title, and phone of the spokesperson: Name: Steven W.Y. LO Title: General Manager Tel.:886-37-871801 Ext. 2900 E-mail:wy.lo @yulon-motor.com.tw Deputy Spokesperson:Wen Yuan Li Title:General Manager Tel.:886-37-871801 Ext. 2400 E-mail:wen-yuan.lee @yulon-motor.com.tw II. Headquarters and plant address: Headquaters: No. 39-1, Bogongkeng, Xihu Village, Sanyi Town, Miaoli County, Taiwan Tel.:886-37- 871801 Plant: No. 39-1, Bogongkeng, Xihu Village, Sanyi Town, Miaoli County, Taiwan Tel.:886-37-871801 Official Website:http//www.yulon-motor.com.tw III. Name, address, and phone of the stock transfer agency: Name: Yulon Motor Co., Ltd. Stock Affairs Office Address: 7F, No. 150, Sec. 2, Nanking E. Road, Taipei City (Hualian Building) Tel.:886-2-2515-6421~5 Official Website:http//www.yulon-motor.com.tw IV. Name, Firm, address, and phone of the acting independent auditors: 2018 Independent Auditors: Hsin-Wei TAI and Yu-Wei FAN CPA Firm: Deloitte & Touche Address: 12F, No. 156, Sec. 3, Minsheng E. Road, Taipei City (Hongtai Century Building) Tel.:886-2-2545-9988 Website:http//www.deloitte.com.tw V. Overseas securities exchange corporation listing: None VI. Corporate Website:http//www.yulon-motor.com.tw Notice to readers This English version annual report is a summary translation of the Chinese version and is not an official document of the shareholders’ meeting. If there is any discrepancy between the English version and Chinese version, the Chinese version shall prevail. -

Acronimos Automotriz

ACRONIMOS AUTOMOTRIZ 0LEV 1AX 1BBL 1BC 1DOF 1HP 1MR 1OHC 1SR 1STR 1TT 1WD 1ZYL 12HOS 2AT 2AV 2AX 2BBL 2BC 2CAM 2CE 2CEO 2CO 2CT 2CV 2CVC 2CW 2DFB 2DH 2DOF 2DP 2DR 2DS 2DV 2DW 2F2F 2GR 2K1 2LH 2LR 2MH 2MHEV 2NH 2OHC 2OHV 2RA 2RM 2RV 2SE 2SF 2SLB 2SO 2SPD 2SR 2SRB 2STR 2TBO 2TP 2TT 2VPC 2WB 2WD 2WLTL 2WS 2WTL 2WV 2ZYL 24HLM 24HN 24HOD 24HRS 3AV 3AX 3BL 3CC 3CE 3CV 3DCC 3DD 3DHB 3DOF 3DR 3DS 3DV 3DW 3GR 3GT 3LH 3LR 3MA 3PB 3PH 3PSB 3PT 3SK 3ST 3STR 3TBO 3VPC 3WC 3WCC 3WD 3WEV 3WH 3WP 3WS 3WT 3WV 3ZYL 4ABS 4ADT 4AT 4AV 4AX 4BBL 4CE 4CL 4CLT 4CV 4DC 4DH 4DR 4DS 4DSC 4DV 4DW 4EAT 4ECT 4ETC 4ETS 4EW 4FV 4GA 4GR 4HLC 4LF 4LH 4LLC 4LR 4LS 4MT 4RA 4RD 4RM 4RT 4SE 4SLB 4SPD 4SRB 4SS 4ST 4STR 4TB 4VPC 4WA 4WABS 4WAL 4WAS 4WB 4WC 4WD 4WDA 4WDB 4WDC 4WDO 4WDR 4WIS 4WOTY 4WS 4WV 4WW 4X2 4X4 4ZYL 5AT 5DHB 5DR 5DS 5DSB 5DV 5DW 5GA 5GR 5MAN 5MT 5SS 5ST 5STR 5VPC 5WC 5WD 5WH 5ZYL 6AT 6CE 6CL 6CM 6DOF 6DR 6GA 6HSP 6MAN 6MT 6RDS 6SS 6ST 6STR 6WD 6WH 6WV 6X6 6ZYL 7SS 7STR 8CL 8CLT 8CM 8CTF 8WD 8X8 8ZYL 9STR A&E A&F A&J A1GP A4K A4WD A5K A7C AAA AAAA AAAFTS AAAM AAAS AAB AABC AABS AAC AACA AACC AACET AACF AACN AAD AADA AADF AADT AADTT AAE AAF AAFEA AAFLS AAFRSR AAG AAGT AAHF AAI AAIA AAITF AAIW AAK AAL AALA AALM AAM AAMA AAMVA AAN AAOL AAP AAPAC AAPC AAPEC AAPEX AAPS AAPTS AAR AARA AARDA AARN AARS AAS AASA AASHTO AASP AASRV AAT AATA AATC AAV AAV8 AAW AAWDC AAWF AAWT AAZ ABA ABAG ABAN ABARS ABB ABC ABCA ABCV ABD ABDC ABE ABEIVA ABFD ABG ABH ABHP ABI ABIAUTO ABK ABL ABLS ABM ABN ABO ABOT ABP ABPV ABR ABRAVE ABRN ABRS ABS ABSA ABSBSC ABSL ABSS ABSSL ABSV ABT ABTT