Bilateralism Under the World Trade Organization Y.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Do Hub-And-Spoke Free Trade Agreements Increase Trade? a Panel Data Analysis

ADB Working Paper Series on Regional Economic Integration Do Hub-and-Spoke Free Trade Agreements Increase Trade? A Panel Data Analysis Joseph Alba, Jung Hur, and Donghyun Park No. 46 | April 2010 ADB Working Paper Series on Regional Economic Integration Do Hub-and-Spoke Free Trade Agreements Increase Trade? A Panel Data Analysis Joseph Alba,+ Jung Hur,++ The authors are grateful to Andrew Rose, Kamal Saggi, and three anonymous referees for their useful comments. The +++ and Donghyun Park usual disclaimer applies. This research is supported by the Sogang University Research Grant. Joseph Alba is grateful for No. 46 April 2010 research funding from Nanyang Technological University. +Joseph Alba is Associate Professor at the Economics Division, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore 639798. Tel +65 6 790 6234, Fax +65 6 792 4217, [email protected] ++Jung Hur is Associate Professor at the Department of Economics, Sogang University 1 Shinsu-Dong, Mapo-Gu, Seoul 121-742, Korea. Tel +82 2 705 8518, Fax +82 2 704 8599, [email protected] +++Donghyun Park is Principal Economist at the Economics and Research Department, Asian Development Bank, Philippines. Tel +63 2 632 5825, Fax +63 2 636 2342, [email protected] The ADB Working Paper Series on Regional Economic Integration focuses on topics relating to regional cooperation and integration in the areas of infrastructure and software, trade and investment, money and finance, and regional public goods. The series is a quick-disseminating, informal publication that seeks to provide information, generate discussion, and elicit comments. Working papers published under this series may subsequently be published elsewhere. -

Bilateral Negotiations and Multilateral Trade: the Case of Taiwan - U.S

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Regionalism versus Multilateral Trade Arrangements, NBER-EASE Volume 6 Volume Author/Editor: Takatoshi Ito and Anne O. Krueger, Eds. Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-38672-4 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/ito_97-1 Publication Date: January 1997 Chapter Title: Bilateral Negotiations and Multilateral Trade: The Case of Taiwan - U.S. Trade Talks Chapter Author: Tain-Jy Chen, Meng-Chun Liu Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8605 Chapter pages in book: (p. 345 - 370) 12 Bilateral Negotiations and Multilateral Trade: The Case of Taiwan-U.S. Trade Talks Thin-Jy Chen and Meng-chun Liu 12.1 Introduction It is widely recognized that the multilateral trading system embodied in the GATT has played an instrumental role in expanding world trade and supporting the phenomenal economic growth the world has experienced since World War 11. Even a nonmember like Taiwan has benefited from access to increasingly open markets in industrial countries, particularly the United States. Immedi- ately after the war, as a hegemonic power, the United States championed multi- lateralism in world trade and led the way in successive multilateral negotiations for trade liberalization. This effort created international public goods on which even a nonmember like Taiwan can ride free. Since the 1970s, however, the United States has resorted with increasing frequency to unilateral measures to solve trade problems. The 1974 US. Trade Law provided the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) with a set of weaponry for practicing unilateralism, such as the Section 301 provision, and strength- ened safeguard measures. -

Indo-Sri Lanka Trade in Services: Fta Ii and Beyond

WORKING PAPER NO. 145 INDO-SRI LANKA TRADE IN SERVICES: FTA II AND BEYOND Nisha Taneja Arpita Mukherjee Sanath Jayanetti Tilani Jayawardane NOVEMBER 2004 INDIAN COUNCIL FOR RESEARCH ON INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC RELATIONS Core-6A, 4th Floor, India Habitat Centre, Lodi Road, New Delhi-110 003 website1: www.icrier.org, website2: www.icrier.res.in INDO-SRI LANKA TRADE IN SERVICES: FTA II AND BEYOND Nisha Taneja Arpita Mukherjee Sanath Jayanetti Tilani Jayawardane NOVEMBER 2004 The views expressed in the ICRIER Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER). Contents List of Tables ......................................................................................................................i List of Abbreviations.........................................................................................................ii Foreword...........................................................................................................................iv I Introduction ...........................................................................................................1 II Analytical Framework ..........................................................................................3 III Methodology ..........................................................................................................5 III.1 Secondary Data..................................................................................................... -

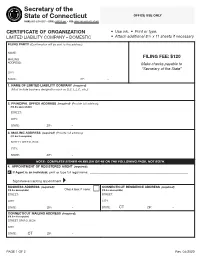

Certificate of Organization (LLC

Secretary of the State of Connecticut OFFICE USE ONLY PHONE: 860-509-6003 • EMAIL: [email protected] • WEB: www.concord-sots.ct.gov CERTIFICATE OF ORGANIZATION • Use ink. • Print or type. LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY – DOMESTIC • Attach additional 8 ½ x 11 sheets if necessary. FILING PARTY (Confirmation will be sent to this address): NAME: FILING FEE: $120 MAILING ADDRESS: Make checks payable to “Secretary of the State” CITY: STATE: ZIP: – 1. NAME OF LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY (required) (Must include business designation such as LLC, L.L.C., etc.): 2. PRINCIPAL OFFICE ADDRESS (required) (Provide full address): (P.O. Box unacceptable) STREET: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – 3. MAILING ADDRESS (required) (Provide full address): (P.O. Box IS acceptable) STREET OR P.O. BOX: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – NOTE: COMPLETE EITHER 4A BELOW OR 4B ON THE FOLLOWING PAGE, NOT BOTH. 4. APPOINTMENT OF REGISTERED AGENT (required): A. If Agent is an individual, print or type full legal name: _______________________________________________________________ Signature accepting appointment ▸ ____________________________________________________________________________________ BUSINESS ADDRESS (required): CONNECTICUT RESIDENCE ADDRESS (required): (P.O. Box unacceptable) Check box if none: (P.O. Box unacceptable) STREET: STREET: CITY: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – STATE: CT ZIP: – CONNECTICUT MAILING ADDRESS (required): (P.O. Box IS acceptable) STREET OR P.O. BOX: CITY: STATE: CT ZIP: – PAGE 1 OF 2 Rev. 04/2020 Secretary of the State of Connecticut OFFICE USE ONLY PHONE: 860-509-6003 • EMAIL: [email protected] -

Organizational Culture Model

A MODEL of ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE By Don Arendt – Dec. 2008 In discussions on the subjects of system safety and safety management, we hear a lot about “safety culture,” but less is said about how these concepts relate to things we can observe, test, and manage. The model in the diagram below can be used to illustrate components of the system, psychological elements of the people in the system and their individual and collective behaviors in terms of system performance. This model is based on work started by Stanford psychologist Albert Bandura in the 1970’s. It’s also featured in E. Scott Geller’s text, The Psychology of Safety Handbook. Bandura called the interaction between these elements “reciprocal determinism.” We don’t need to know that but it basically means that the elements in the system can cause each other. One element can affect the others or be affected by the others. System and Environment The first element we should consider is the system/environment element. This is where the processes of the SMS “live.” This is also the most tangible of the elements and the one that can be most directly affected by management actions. The organization’s policy, organizational structure, accountability frameworks, procedures, controls, facilities, equipment, and software that make up the workplace conditions under which employees work all reside in this element. Elements of the operational environment such as markets, industry standards, legal and regulatory frameworks, and business relations such as contracts and alliances also affect the make up part of the system’s environment. These elements together form the vital underpinnings of this thing we call “culture.” Psychology The next element, the psychological element, concerns how the people in the organization think and feel about various aspects of organizational performance, including safety. -

How Do Exports and Imports Affect the Use of Free Trade Agreements? Firm-Level Survey Evidence from Southeast Asia

ERIA-DP-2016-01 ERIA Discussion Paper Series How Do Exports and Imports Affect the Use of Free Trade Agreements? Firm-level Survey Evidence from Southeast Asia Lili Yan ING* Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA) and University of Indonesia Shujiro URATA ERIA and Waseda University Yoshifumi FUKUNAGA Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA) January 2016 Abstract: Based on profit estimations, findings from a firm-level survey of 630 manufacturing firms across Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries conducted in 2013 showed that a 1 percent increase in the share of exports in total sales will increase the probability of use of free trade agreements (FTAs) by 0.2 percent, whereas a 1 percent increase in the share of imports in total inputs will reduce the probability of use of FTAs by 0.4 percent. Results from locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) show that the use of FTAs is tilde-shaped and negative-shaped as a function of exports and imports, respectively. Keywords: Free Trade Agreement, ASEAN, Regional integration, FTA Utilisation JEL: F14, F15, F16, F23, F6 * The authors thank national teams for their work on leading surveys in Southeast Asia – MOFAT for Brunei Darussalam, CICP for Cambodia, LPEM–FEUI for Indonesia, NERI for Lao PDR, MIER Malaysia, YIE for Myanmar, PIDS for the Philippines, SIIA for Singapore, University of Chulalongkorn for Thailand, and CIEM for Viet Nam. The authors thank Ikumo Isono and Archanun Koophaiboon, and participants at the 14th East Asian Economic Association Conference for their comments on an earlier draft, and Robert Herdiyanto for his assistance in data cleaning at an early stage of the survey, and Rully Prassetya and Muhammad Rizqy for checking the use of GSP. -

Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship

Abilene Christian University Digital Commons @ ACU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-2019 Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship Jacob Martin [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Martin, Jacob, "Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship" (2019). Digital Commons @ ACU, Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 124. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ACU. This dissertation, directed and approved by the candidate’s committee, has been accepted by the College of Graduate and Professional Studies of Abilene Christian University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Education in Organizational Leadership Dr. Joey Cope, Dean of the College of Graduate and Professional Studies Date Dissertation Committee: Dr. First Name Last Name, Chair Dr. First Name Last Name Dr. First Name Last Name Abilene Christian University School of Educational Leadership Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Organizational Leadership by Jacob Martin December 2018 i Acknowledgments I would not have been able to complete this journey without the support of my family. My wife, Christal, has especially been supportive, and I greatly appreciate her patience with the many hours this has taken over the last few years. I also owe gratitude for the extra push and timely encouragement from my parents, Joe Don and Janet, and my granddad Dee. -

FTA Tariff Tool New Online Tool Highlights Tariff Benefits of Free Trade Agreements for American Businesses

U.S. Department of Commerce International Trade Administration FTA Tariff Tool New Online Tool Highlights Tariff Benefits of Free Trade Agreements for American Businesses http://www.export.gov/FTA/FTATariffTool/ • Are you an exporter seeking a market where the United States The FTA Tariff Tool: has an existing competitive advantage? • Are you spending time looking through pages of legal texts • consolidates and distills tariff to figure out the tariff under a trade agreement for your schedules down to a simple products? search function • Would you like to perform instant and at-a-glance searches • allows users to see how for trade and tariff trends in one easily accessed location particular sectors are treated online? under the agreements or recent trends in exports to the trade The Free Trade Agreement (FTA) Tariff Tool will ease your exporting agreement partner markets process and could help you increase your exports to U.S. trade agreement partner markets. It will streamline your industrial and • helps reduce costs and consumer product tariff searches by making information on tariff uncertainty for U.S. businesses benefits companies receive under U.S. trade agreements more accessible. The FTA Tariff Tool consolidates and condenses trade, tariff and sectoral information into a user-friendly public interface. The tool is provided free of charge by the U.S. Department of Commerce. Businesses are able to see the current and future tariffs applied to their products, as well as the date on which those products become duty free. By combining sector and product groups, trade data, and the tariff elimination schedules, users can also analyze how various sectors are treated across multiple trade agreements. -

English Business Organization Law During the Industrial Revolution

Choosing the Partnership: English Business Organization Law During the Industrial Revolution Ryan Bubb* I. INTRODUCTION For most of the period associated with the Industrial Revolution in Britain, English law restricted access to incorporation and the Bubble Act explicitly outlawed the formation of unincorporated joint stock com- panies with transferable shares. Furthermore, firms in the manufacturing industries most closely associated with the Industrial Revolution were overwhelmingly partnerships. These two facts have led some scholars to posit that the antiquated business organization law was a constraint on the structural transformation and growth that characterized the British economy during the period. For example, Professor Ron Harris argues that the limitation on the joint stock form was “less than satisfactory in terms of overall social costs, efficient allocation of resources, and even- 1 tually the rate of growth of the English economy.” * Associate Professor of Law, New York University School of Law. Email: [email protected]. For helpful comments I am grateful to Ed Glaeser, Ron Harris, Eric Hilt, Giacomo Ponzetto, Max Schanzenbach, and participants in the Berle VI Symposium at Seattle University Law School, the NYU Legal History Colloquium, and the Harvard Economic History Tea. I thank Alex Seretakis for superb research assistance. 1. RON HARRIS, INDUSTRIALIZING ENGLISH LAW: ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND BUSINESS ORGANIZATION, 1720–1844, at 167 (2000). There are numerous other examples of this and related arguments in the literature. While acknowledging that, to a large extent, restrictions on the joint stock form could be overcome by alternative arrangements, Nick Crafts nonetheless argues that “institutional weaknesses relating to . company legislation . must have had some inhibiting effects both on savers and on business investment.” Nick Crafts, The Industrial Revolution, in 1 THE ECONOMIC HISTORY OF BRITAIN SINCE 1700, at 44, 52 (Roderick Floud & Donald N. -

ASSESSING the IMPACT of TRADE AGREEMENTS on GENDER EQUALITY: Canada-EU Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement

GENDER AND TRADE ASSESSING THE IMPACT OF TRADE AGREEMENTS ON GENDER EQUALITY: Canada-EU Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement GENDER AND TRADE ASSESSING THE IMPACT OF TRADE AGREEMENTS ON GENDER EQUALITY: Canada-EU Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement WE EMPOWER, EUROPEAN UNION, UN Women and ILO WE EMPOWER – G7: The Promoting the Economic Empowerment of Women at Work through Responsible Business Conduct in G7 Countries (WE EMPOWER – G7) programme is funded by the European Union (EU) and implemented by UN Women and the International Labour Organization. WE EMPOWER – G7 convenes multistakeholder dialogues in G7 countries and the EU to exchange knowledge, experiences, good practices and lessons learned. WE EMPOWER – G7 also encourages firms of all sizes and in all industries to sign the Women’s Empowerment Principles and to galvanize their shareholders and stakeholders throughout their supply chains to drive change for gender equality. Signatories are role models for attracting talent role models for attracting talent, entering new markets and serving their communities, while measurably improving the bottom line. See more at: www.empowerwomen.org/projects. The European Union is the largest trading block in the world. The EU is committed to sustainable development and gender equality. It is working to integrate gender perspective in its trade policy, including through trade agreements such as the CETA with Canada. Work on trade and gender is advancing through a wide range of actions in the following areas: (1) data and analysis, (2) gender provisions in trade agreements, and (3) trade and gender in the WTO. UN Women is the UN organization dedicated to gender equality and women’s empowerment. -

A Guide to Nonprofit Board Service in Oregon

A GUIDE TO NONPROFIT BOARD SERVICE IN OREGON Office of the Attorney General A GUIDE TO NONPROFIT BOARD SERVICE Dear Board Member: Thank you for serving as a director of a nonprofit charitable corporation. Oregonians rely heavily on charitable corporations to provide many public benefits, and our quality of life is dependent upon the many volunteer directors who are willing to give of their time and talents. Although charitable corporations vary a great deal in size, structure and mission, there are a number of principles which apply to all such organizations. This guide is provided by the Attorney General’s office to assist board members in performing these important functions. It is only a guide and is not meant to suggest the exact manner that board members must act in all situations. Specific legal questions should be directed to your attorney. Nevertheless, we believe that this guide will help you understand the three “R”s associated with your board participation: your role, your rights, and your responsibilities. Active participation in charitable causes is critical to improving the quality of life for all Oregonians. On behalf of the public, I appreciate your dedicated service. Sincerely, Ellen F. Rosenblum Attorney General 1 UNDERSTANDING YOUR ROLE Board members are recruited for a variety of reasons. Some individuals are talented fundraisers and are sought by charities for that reason. Others bring credibility and prestige to an organization. But whatever the other reasons for service, the principal role of the board member is stewardship. The directors of the corporation are ultimately responsible for the management of the affairs of the charity. -

Bilateralism Jeffrey W

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Political Science Faculty Publications Political Science 2008 Bilateralism Jeffrey W. Legro University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/polisci-faculty-publications Part of the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Legro, Jeffrey W. "Bilateralism." In International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, volume 1, 2nd edition, edited by William A Darity, Jr., 296-297. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2008. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bilateralism Although interest in studying bigotry has varied over against women and the paradoxical intimacy that charac- the years, a renewed interest in the topic is evident among terizes relations between heterosexual males and females, researchers addressing issues related to cyberhate, terror- it becomes clear that contact, while necessary, is not suffi- ism, and religious and nationalistic fanaticism. In the case cient to eliminate bigotry. Furthermore, there is relatively of cyberhate, the speed of the Internet and its widespread little research investigating the extent to which contact accessibility make the spread of bigotry almost instanta- between different real-world racial and ethnic groups can neous and increasingly available to vulnerable populations actually breed harmony. How then to solve the problem of (Craig-Henderson 2006). As for the relationship between bigotry? The best strategy is one that includes education, bigotry and nationalism, there are a host of researchers interaction, and legislation.