Discovering the Baltics? Think Tallinn!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

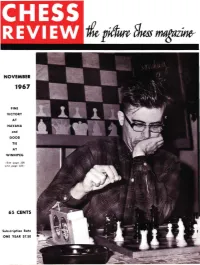

CR1967 11.Pdf

NOVEMBER 1967 FINE VICTORY AT HAVANA and GOOD TIE AT WINNIPEG ( Set PllO" ) 2$ .:ond pig" 323) 65 CENTS Subscription Rat. ONE YEAR 57.50 e wn 789 7 'h by 9 Inches. clothbound 221 diagrams 493 idea Yariations 1704 practical yariations 463 supplementary variations 3894 notes to all yariations and 439 COMPLETE GAMES! BY I. A . HOROWITZ in collaboration with Former World Champion, Dr. Max Euwe. Ernest Gruenfeld, Hans Kmoch. and many other noted authorities This latest Hild immense work, the most exhaustive of its kind, ex· plains in encyclopedic detail the fine points of all openings. It carries the reader well into the middle game, evaluates the prospects there and often gives complete exemplary games so that he is not left hanging in mid.position with the query: What happens now? A logical sequence binds the continuity in each opening. First come the moves with footnotes leading to the key positi on. Then fol· BIBLIOPHILES! low pertinent observations, illustrated by " Idea Variations." Finally, Glossy paper, handsome print, Practical and Supplementary Va riations, well annotated, exemplify the spaciolls paging and all the effective po::isibilities. Each line is appraised: +. - or =. The hi rge format- 71f2 x 9 inches-is designed for ease of read· other appurtenances of exqllis ing and playing. It eliminates much tiresome shuIIling of pages ite book-making combine to between the principal Jines and the respective comments. Clear, make this the handsomest of legible type, a wide margin for inserting notes and variation-identify. ing diagrams are olher plus features. chess books! In addition to all else. -

Baltic Journal of European Studies ISSN 2228-0588

BALTIC JOURNAL OF EUROPEAN STUDIes ISSN 2228-0588 Vol 1, No 2 (10) September 2011 Foreword .............................................................................................................................. 3 Notes on Contributors .......................................................................................................... 4 ARTICLES András Inotai. Impact of the Global Crisis on EU–China Relations: Facts, Opportunities and Potential Risks .................................................................................. 7 Andrea Éltető. Portugal and Spain: Causes and Effects of the Crisis ............................. 34 Alina Christova. The European Stability Mechanism: Progress or Missed Opportunity? ................................................................................................................. 49 Tiia Püss, Mare Viies, Reet Maldre. Social Systems in the Baltic States and the European Social Model ................................................................................................ 59 Helbe Põdder. Employment of Mothers and Fathers: A Comparison of Welfare States in Scandinavia and Estonia ........................................................................................... 85 Vlad Vernygora. Prospects for New Zealand in the Baltic States: Theoretical, Structural and Operational Dimensions of Cooperation ..............................................103 Tuuli Lähdesmäki. Contested Identity Politics: Analysis of the EU Policy Objectives and the Local Reception of the European -

New Zealand Chess Supplies P.O

NEW ZEALAND CHESS SUPPLIES P.O. Box 42-O9O Wainuiomata Phone (04)564-8578 Fax(04)564-8578 New Zealand Mail order and wholesale stockists of the widest selection of modern chess literature in Australasia. Chess sets, boards, clocks, stationery and all playing equipment. Chess Distributors of all leading brands of chess computers and software Send S.A.E. for brochure and catalogue (state your interest). Tho official magazhe of tho New Zealmd Chess Federation PLASTIC CHESSMEN (STAUNTON STYLE} 67mm King (boxed) solid and felt-based 913.50 95mm King (in plastic bag) solid, weighted, felt-based $17.50 95mm King (in plastic box with lid), as above 524.OO I Volume 20 Number 4 August 1994 $3.00 (inc GST) FOLDING CHESSBOARDS - CLUB/TOURNAMENT STANDARD 36Ommx36Omm thick cardboard (black and white squares) $5.OO 425mmx425mm Corflute plastic (dark brown and white) S5.OO 48Ommx48Omm thick cardboard (green and lemon) $6.00 VINYL CHESSBOARDS . CLUB/TOURNAMENT STANDARD 425mmx425mm roll-up mat type, algebraic symbols at borders to assist move recognition (brown and white) $7.OO 44Ommx44Omm semi-flex and non-folding, algebraic symbols as above (dark brown and off-white) $8.OO FOLDING MAGNETIC CHESS WALLETS (DABK GREEN VINYL} 1 9Ox 1 5Omm (1 Smm squares) f lat disk pieces $ 1 7.5O 27Ox2OOmm (24mm squares) f lat square pieces S 15.OO A'\^ride range of fine wood sets and boards also stocked CHESS MOVE TIMERS (CLOCKS} Turnier German-made popular club clock, brown plastic $69.00 Standard German-made as above, in imitation wood case $79.OO CLUB AND TOURNAMENT -

Nuestro Círculo

Nuestro Círculo Año 10 Nº 460 Semanario de Ajedrez 28 de mayo de 2011 ORTVIN SARAPU Txe5 27.fxe5 Te8 28.Tf6 Rg8 29.h4 Dd7 Ortvin Sarapu - Sergio Giardelli [A07] 30.Dd4 De7 31.e6 Dg7 32.Df4 h6 33.Cf7 Buenos Aries, 1978 1924 – 1999 Txe6 34.Cxh6+ Rh7 35.Cg4 Te4 36.h5 Txf4 37.hxg6+ Dxg6 38.Txf4 Db1+ 39.Rh2 Db2 0- 1.e4 c5 2.Ce2 e6 3.Cbc3 a6 4.g3 Cc6 5.Ag2 1 d6 6.0-0 Dc7 7.d3 Cf6 8.Ae3 Ae7 9.Rh1 0-0 Sarapu,O - Frankel,Z [C44] 10.f4 b5 11.Dd2 b4 12.Cd1 Ad7 13.Ag1 a5 New Zelanda, 1962 14.Ce3 Tac8 15.g4 Cd4 16.g5 Ce8 17.Cg3 f6 18.h4 Ac6 19.c3 Cb5 20.Ah2 Dd7 21.Ah3 f5 1.e4 e5 2.Cf3 Cc6 3.d4 exd4 4.c3 d5 5.exd5 22.Ag2 Cec7 23.Cc4 Tb8 24.Cxa5 Aa8 Dxd5 6.cxd4 Ab4+ 7.Cc3 Cf6 8.Ae2 0-0 9.0-0 25.Cc4 d5 26.Ce5 Dd6 27.exf5 exf5 28.Ce2 Df5 10.h3 Te8 11.Ad3 Dd7 12.a3 Af8 13.Af4 Ce6 29.d4 Tfd8 30.Ag1 bxc3 31.bxc3 Dc7 Cd8 14.d5 a6 15.Ce5 De7 16.Te1 g6 17.Dd2 32.Cg3 Cd6 33.De3 cxd4 34.cxd4 Cf8 Dc5 18.b4 Da7 19.Ae3 Db8 20.Ad4 c5 35.Tfe1 Te8 36.h5 Tb2 37.Cd3 Tc2 38.De5 21.dxc6 bxc6 22.Cxg6 hxg6 23.Axf6 Txe1+ Dc4 39.h6 Af6 40.Dxd6 Dxd3 41.Txe8 1-0 24.Txe1 Ae6 25.Ce4 Ad5 26.Dg5 Ce6 27.Dh4 Cg7 28.Cg5 Ch5 29.Dxh5 gxh5 Paul Keres - Ortvin Sarapu [B74] 30.Ah7# 1-0 Correspondence, 1961 Fischer - Sarapu [C13] Sousse, 1967 1.e4 c5 2.Cf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Cxd4 Cf6 5.Cc3 g6 6.Ae2 Ag7 7.Ae3 Cc6 8.0-0 0-0 9.Cb3 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Cc3 dxe4 4.Cxe4 Cd7 Ae6 10.f4 Tc8 11.f5 Ad7 12.g4 Ce5 13.Cd2 5.Cf3 Cgf6 6.Cxf6+ Cxf6 7.Ag5 c5 8.Ab5+ gxf5 14.exf5 Rh8 15.g5 Tg8 16.Tf2 Da5 Ad7 9.Axd7+ Dxd7 10.De2 cxd4 11.0-0-0 17.Cb3 Dd8 18.Tg2 Txc3 19.bxc3 Ce4 Ortvin Sarapu nació en Nava, Estonia, el 22 - Ac5 12.De5 Ae7 13.Cxd4 Tc8 14.f4 0-0 20.Cd4 Cxc3 21.Dd2 Cxe2+ 22.Dxe2 Cc6 1-1924 y murió en Auckland, Nueva Zelanda 15.Cf5 Dc7 16.Cxe7+ Dxe7 17.Td2 Tc5 23.Dd3 Axf5 24.Cxf5 Axa1 25.c3 Da5 el 13-4-1999). -

New Zealand Chess

NEW ZEALAND CHESS SUPPLIES P.O.Box 42-O9O Wainuiomata New Zealand Phone (04)s64€578 Fax (04)s64{578 Mall order and wholeeale stocklsts ol the wldest selectlon of modetn chess literature ln Australasla- and all playing equiPment Chess Chess sets, boards, clocks, stationery Distributors ol all leading brands ol chess comPuters and software. Send S.A.E. for brochure and catalogue (state your interest). ESSMEN'STAU NTON' STYLE - CLU B/TOU RNAMENT STAN DARD PLASTIC CH Oflicial magazine of the New Zealand Chess Federation (Inc.) 90mm King, solid, extra weighted, wide felt base (ivory & black matt finish) $28.00 felt base (black & white semi-gloss finish) $17.50 95mm King solid, weighted, Vol 23 Number I February 1997 $3.50 (incl GST) Plastic container with clip tight lid for above sets $8.00 FOLDING CHESSBOARDS - CLUB/TOURNAMENT STANDARD 48o x 48omm thick cardboard (green and lemon) $O.oO 450 x 45o mm thick vinyl (dark brown and otf white) $14.50 VINYL CHESSBOARDS - CLUB/TOURNAMENT STANDARD 450 x 470 mm roll-up mat type, algebraic symbols at borders to assist move recognition (green and white) $8.00 440 x 44omm semi-flex and non{olding, algebraic symbols as above (dark brown and off-white) $9.00 CHESS MOVE TIMERS (CLOCKS) Turnier German-made popular win*up club clock, brown plastic $69.00 Standard German-made as above, in imitation wood case $79.00 DGT official FIDE digital chess timer $169.00 SAITEK digital game timer $145.00 CLUB AND TOURNAMENT STATIONERY Bundle of 2@ loose score sheets, 80 moves and diagram $Z'oo Bundle of 5oo loose score -

New Zealand Chess

IUEW ZEALAilD CHESS SUPPLIES P.O.Box 42-090 Wal nulo mata Phone (04)564-8578 Fax (04)564-8578 New Zealand Mall order and wholesale stocklsts of the wldest selecflon of modern chess llterature ln A6tralasla. Chess sets, boards, clocks, statlonery and all playlng equlpment. Dlstrlbutors of all leadlng brands of chess computers and software. Send S.A.E. for brochure and catalogue (state your lnterest). Chess PLASTIC CHESSMEN (STAUNTON STYLE) 67mm King (boxed) solid and felt-based $13.50 95mm King (in plastic bag) so1id, weighted, felt-based $17.50 Offrcial magazne of the New ZealadChes Fedmtion (Inc ) 95mm King (in plastic box, with 1id), as above $25.50 FOLDING CHESSBOARDS - CLUB/TOURNAI4ENT STANDARD 360x360mn thick cardboard (black and white squares) $5.00 480x480mm thick cardboard (green and lemon) $6.00 Vol2lNumber4 Augustlgg5 $3.00(inclGST) VINYL CHESSBOARDS - CLUB/TOURNA}4ENT STANDARD 425x425nn ro11-up mat type, algebraic symbols at borders to assist move recognition (brown and white) $8.00 440x440mm semi-flex and non-fo1ding, algebraic symbols as above (dark brown and off-white) $9.00 FOLDING I'IAGNETIC CHESS WALLETS (DARK GREEN VINYL) 190x150mm (lSnm squares) flat disk pieces $.19.50 270x200m (24mm squares) flat square pieces $15.00 A wlde range of flne wood sets and boads also stocked 450x450rm inlaid wood (Sheesham 50mm squares) $75.00 CHESS I.,IOVE TIMERS (CLOCKS) Turnier German-made popular club clock, brown plastic $G9.00 Standard German-nnde as above, in imitation wood case S79.00 DGT official FIDE chess clock $169.00 CLUB AND TOURNAI4ENT STATIONERY Bundles of loose score sheets, 200 $7.00 80 moves and diagram 500 t1s.00 2000 $s0.00 Score pad, spiral-bound, 50 games, score sheets as above $3. -

Notabadthing Tohavestamped

MadeinGermaRy. NEW ZE.ALAND CHESS Notabadthing magazine. Registered at Post Office Headquarters, Wellington as a tohavestamped Vol. 7 No.s October 1981 8O cents onyour next flight. I I t ii i I Look lor this sign when you shop for travel Themoreyou fly $,,lurthansa GERMAN AIRLINES on the title again. Royal Inaurance Bldg. Viktor Korchnoi- - trail 109-113 Quoon St., Auckland, N.Z. Tel.: 31529 P.O. Box 1427 NEW ZEALAND CIIESS is published bi-monthly by the New Zealand Chess Association, P.0. Box 8802, Synonds St, Auckland. Months of issue are February, Aprl1, Junr,, August, October and December. NEW ZE.ALAND CHESS Unless otherwise stated, the views exptessed may not necessarily be ttrose of rhl As sociation. Vol. 7 No.S October 1981 whether they are in a national team. In this case NZCA coirncil elearly EDITOR: Robert trl. Snith, L0 Lendic Avenue Henderso:r, Auckland 8. EIIITlIRIAT vacillated Eoo long and put iEs eggs in This editorial may well draw some dis_ too fehl baskets. ASSoCIATE EDIToRS: Peter Stuart, Ortvin Sarapu llt,f{BE, Tony Dowden(otago), Michael approvBl-, but there ar€t some points that If people are going to take ti4,o or & Smll(Canterbury). Ltrite(WellinBton) Vernon I feel I must make. three wee'ks off work to compete in such I will be competing in China as a merir_ a competition they need time to make the A11 contributions shorrld be sent to the Editorrs address, Unused mnuscripts will ber of the New Zealand Team for the Asian necessary arrangements, returned unless a stafiped, addressed envelope is enclosed. -

Lufthansa 747Sto Europe City Aucktaild 109 Queen Street Telephone 31 Szalsls2g New Zealand Sludy Composer Emil Melnjchenko I

NEw ZEALAND t CHESS J:"" Resistered at post orrice Ho, werinston as a masazine AUGUST 1983 Lufthansa 747sto Europe City AUCKtAilD 109 Queen Street Telephone 31 SZAlSlS2g New Zealand sLudy composer Emil Melnjchenko I NEW ZEALAND CHESS is published bi-nonthly (February, April, June, NEW ZEALAND CHESS Vol.9 No.4 AUGUST 1983 August, October & December) by the SETS New Zealand Chess Association. Back in stock are the popular plastic, Editori PETER STUART Unless otherwise stated, the views Staunton pattern chess sets - narrow Associate Editorsi T0NY DOITJDEN (otago), VERN0N SlvlALL 1canter.uurq), expressed may not necessarily be base variety, king height 9.5 cn, MICHAEL WHIfE (wettinqton), IM ORTVIN SARAPU those of the Association. Price: 1 -9, $S.50 each; 10+, $8.50 each CANDIDATES BROUHAHA competing successfully at a Los Angeles ADDRESSES BOARDS meet at about the same timel semifinal matches, Kasparov v In any event, one cannot have very A11 articles, letters to the Editor, A new chess board in rigid plastic, The two Korchnoi and Ribli v Smyslov, were much syupathy for the Soviet position etc should be sent to the Editor, 5.3cm squares, brorrm & white, available originally due to start by the end of in view of their delay in first pro- P.W, Stuart, 24 Seacliffe Avenue, folding or non-folding. 0n1y fron NZCA! July but, following strenuous objections testing the venues and then givlng Takapuna, Auckland 9. Unpublished Price: 1-9, $3.50 each; 10*, $3.00 each manuscripts cannot be returned to the playing venues by the USSR Chess their reasons; it is almost as thou8h unless a stamped, addressed return Federation, both mtches have been post- they wished to ensure that there would envelope is enclosed. -

NEW ZEALAND CHESS SUPPLIES P.O.Box 42-O9O Wainuiomata New Zealand Phone(04)564-8578 Fax(04)564-8578

.Z NEW ZEALAND CHESS SUPPLIES P.O.Box 42-O9O Wainuiomata New Zealand Phone(04)564-8578 Fax(04)564-8578 Emai I : [email protected] Mail order and wholesale stockists of the widest selection Chess of modern chess literature in Australasia. Chess sets, boards, clocks, stationery and all playing equipment. Distributors of all leading brands of chess computers and software. Ollicial nragazine of the Ncw Zcaland Chcss Fcdcration ([nc) Send S.A.E. for brochure and catalogue (state your interest). PLASTIC CHESSMEN 'STAUNTON' STYLE - CLUE/TOURNAMENT STANDARD 90mm King, solid, extra weighted, wide felt base (ivory & black matt finish)$28.00 95mm King solid, weighted, felt base (black & white semi-gloss finish) $17.50 Vol 2-5 Number 4 August 1999 $3.50 (inc GST) 98mm King solid, weighted, felt base (black & white matt finish) $24.50 Plastic container with clip tight lid for above sets $8.00 FOLDING CHESSBOARDS - CLUB/TOURNAMENT STANDARD 480 x 480mm thick cardboard (green and lemon) $6.00 450 x 450 mm thick vinyl (dark brown and off white) $19.50 VINYL CHESSBOARDS - CLUB/TOURNAMENT STANDARD 450 x 470 mm roll-up mat type, algebraic symbols at borders to assist move recognition (green and white) $8.00 440 x 44omm semi{lex and non{olding, algebraic symbols as above (dark brown and off-white) $9.00 cHESS MOVE TTMERS (CLOCKS) Turnier German-made popular wind-up club clock, brown plastic $80.00 Standard German-made as above, in imitation wood case $88.00 DGT official FIDE digital chess timer $169.00 SAITEK digital game timer $129.00 CLUB AND -

January 2011 Volume 38 Number 1

New Zealand Chess Magazine of the New Zealand Chess Federation (Inc) January 2011 Volume 38 Number 1 GM Zong-Yuan Zhao wins Rotorua Oceania Zonal The 118th Congress - IM Anthony Ker's 12th NZ Championship Title Official publication of the New Contents Zealand Chess Federation (Inc) 3 118th Congress Report Published January 1, April 1, July 1, October 1 by Bill Forster 12 2011 Oceania Zonal – Please send all reports, letters and other Tournament Report contributions to the Editor at [email protected]. by Alan Aldridge 18 Endgame Workshop – The six Please use annotated pgn or ChessBase square system revisited format exclusively for chess material. by IM Herman van Riemsdijk Editorial 23 Book Review Editor Alan Aldridge Technical Editor Bill Forster by Leonard McLaren [email protected] 24 b2 or not b2? That is the Question!- Part 2 Annual Subscription Rates NZ: $24.00 plus postage $4.00 total by Steve Willard $28.00 27 Letter from the Kingside – International: NZD24.00 plus postage How Many Titles NZD12.00 by Roger Nokes Advertising Rates Full page $50.00 Half Page Horizontal $30.00 Quarter page Horizontal $20.00 NZCF Contact Details New Zealand Chess Federation (Inc) PO Box 216 Shortland Street Auckland Secretary Helen Milligan Play through published games and others online at www.nzchessmag.com NZ Chess Magazine January 2011 2 IM Anthony Ker wins his 12th New Zealand Championship at the 118th Congress By Bill Forster nthony Ker put his name of the Asilver rook for the twelfth time at the 118th Congress held in January at the Alexandra Park raceway in Auckland. -

Notabadthing Tohavestamped

MadeinGermany. Notabadthing I NEW ZE.ALAND CHESS Registered at Post Office Headquarters, Wellington as a magazine. tohavestamped Vol.7 No.1 February 1981 80 cents onyour next flight. Look for this sign when you shop for travel Themoneyou fly New Zealand Men's Chess Team departing for Ma1ta. From left: P.Stuart (Captain), O.Sarapu, L.Aptekar, B.Anderson and V.Small. Olympiad reports inside. @lurthansaGERMAN AIBLlNES Royal lnsurance Bldg. 109-113 Oueen Sl., Auckland, N.Z. Tel,: 31529 P.O. Bor 1427 NEl^l ZEALAND CHESS is published bi-nonrhly by the New Zealand chess Associatlon, NEW ZE.ALAND CHESS P.O. Box 8802, Synonds Street, Auckland. Months of issue are I'ebruary, Aprl1, June, August, October and December. unless otherwise stated, the vielrs expressed may not necessarily be those of the Association. Vol.7 No.1 February 1 981 Editorial Wlth this lssue I will have completed 3 P.Sinton. one year as edi.tor of New Zealand Chess. Swiss (Cle11and Trophy): I G.Haase 6\18, It has been an enjoyable year for me but 2-3 J.Sievey & M.Ioord 6, 4 D,Cameron 5. rather a hectic one. The most difficult A gare from the Swlss: task of the edilor is getting an lssue G.HMSE - D.WEEGENMR, Bird's 0pening: out on time r^rith the maxlmum amount of 1 f4 Nf5 2 Nf3 3 b3 Bg7 4 Bb2 o-0 Overseas the 96 \ up-to-date news. news is 5 93 b6 6 Bg2 Bb7 7 0-O d6 8 d3 NbdT trlckiest because it invariably arrives 9 Nbd2 e5 10 Nh4 Bxg2 11 Nxg2 Qe7 the day before you had planned taking 12 e4 Nh5? 13 f5 d5 14 Ktrl dxe4 inEo prl-ntersl the copy the 15 Nxe4 RadB 16 Qe2 Nhf6 17 Ne3 c5 The new editor of New Zealand Chess 18 a4 Nb8 19 Qf3 Nc6 20 Nxf6+ Qxf6 (as April 1981 issue) will be fron the 21 Qe4 Qd6 22 Rf2 Nd4 23 Rafl gxf5 Robert Smith and all contributions 24 Nxf5 Nxf5 25 Rxf5 f6 26 Kg2 Qe5 should now be sent to his address at: 27 Qg4 IcrB 28 Qe4 Qe8 29 Qf3 Qs5 9 James Laurle Road, 30 Rf2 RfeS 31 h4 Kg8 32 h5 Qh6 Ilenders on, 33 Bc3l Bh8 34 Bdz Qg7 35 Be3 Rd6 Auckland 9. -

Gm Walter Browne 1949-2015

IM Chandra Wins U.S. Junior Closed| GM Lenderman Wins World Open GM WALTER BROWNE 1949-2015 October 2015 | USChess.org IFC_chess life 9/5/2015 12:08 AM Page 1 CL_10-2015_K-12_Advertisment_FB_r2.qxp_chess life 11/09/2015 04:29 Page 1 2015 NATIONAL K-12 GRADE CHAMPIONSHIPS DECEMBER 4-6, 2015 DISNEY’S CORONADO SPRINGS RESORT, 1000 WEST BUENA VISTA DR., LAKE BUENA VISTA, FL 32830 $129 single/double/triple/quad OPENING CEREMONY 7SS, G/90 D5 13 SECTIONS Play only in your grade. November 2015 Friday: 12:30 pm rating supplement will be used. Team Score = total of top three (minimum two) finishers from each school per grade. First place individual and team, ROUNDS including ties, will be national champion for their grade. Friday: 1 pm, 6 pm Trophies to top individuals & top teams in each grade. Saturday: 10 am, 2 pm, 6 pm AWARDS Every participant receives a commemorative item! Full list of trophies Sunday: 9 am, 1 pm on tournament info page. AWARD CEREMONIES BLITZ Trophies in K-6 and K-12 sections. Full list of trophies on Sunday: 4:30 pm (K-1) approx. tournament info page. & 5 pm approx. BUGHOUSE Top five teams. SPECIAL ROUND TIMES FOR K-1 SECTIONS Friday: 1:30 pm, 5:30 pm SIDE EVENTS Saturday: 9:30 am, 1:30 & 5:30 pm Sunday: 9:30 am, 1:30 pm BUGHOUSE Thursday: 11 am Reg. onsite only Thurs. 9-10 am. $25/team. ON-SITE REGISTRATION BLITZ Thursday: 5 pm Reg. onsite until 4 pm. Entry in advance $15 12/3: 9 am-9:00 pm by 11/23, $20 after or at site.