The Nature and Quality of Australian Supermarkets' Policies That Can Impact Public Health Nutrition, and Evidence of Their Practical Application

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kaufland Australia Proposed Store Mornington, Melbourne Economic Impact Assessment

Kaufland Australia Proposed store Mornington, Melbourne Economic Impact Assessment November 2018 Prepared by: Anthony Dimasi, Managing Director – Dimasi & Co [email protected] Prepared for Kaufland Australia Table of contents Executive summary 1 Introduction 5 Section 1: The supermarket sector – Australia and Victoria 6 Section 2: Kaufland Australia – store format and offer 13 Section 3: Economic Impact Assessment 20 3.1 Site location and context 21 3.2 Trade area analysis 23 3.3 Competition analysis 27 3.4 Estimated sales potential 28 3.5 Economic impacts 30 3.6 Net community benefit assessment 43 Executive summary The Supermarkets & Grocery Stores category is by far the most important retail category in Australia. Total sales recorded by Supermarkets & Grocery Stores as measured by the Australian Bureau of Statistics have increased from $64.5 billion at 2007 to $103.7 billion at 2017, recording average annual growth of 4.9% per annum – despite the impacts of the global financial crisis (GFC). Over this past decade the category has also increased its share of total Australian retail sales from 31.3% to 33.7%. For Victoria, similar trends are evident. Supermarkets and grocery stores’ sales have increased over the past decade at a similar rate to the national average – 4.5% versus 4.9%. The share of total retail sales directed to supermarkets and grocery stores by Victorians has also increased over this period, from 31.6% at 2007 to 32.8% at 2017. Given the importance of the Supermarkets & Grocery Stores category to both the Victorian retail sector and Victorian consumers, the entry of Kaufland into the supermarket sector brings with it enormous potential for significant consumer benefits, as well as broader economic benefits. -

Supermarket Refrigeration Going Natural

cover story >>> SEAN McGOWAN REPORTS Supermarket refrigeration going natural In 2005, Coles Supermarkets opened its first ‘environmental concept’ supermarket featuring a cascade carbon dioxide refrigeration system. Two years on the technology has undergone significant improvement to better serve the local market, while internationally it promises to receive widespread adoption by the world’s retail heavyweights, as Sean McGowan reports. Supermarket refrigeration accounts for a significant 1% of Australia’s total electricity consumption, and this figure is reported to be higher in Europe and the United States. Therefore, its not surprising to find supermarket chains worldwide clamoring to adopt new technology which promises to cut their energy costs, while at the same time, address their corporate responsibilities to the environment and the communities who shop with them. The knight in shining armour looks set to be carbon dioxide (CO2) refrigeration systems, which are often used in a cascade design with fluorocarbon refrigerants such as R507 or R134a. A cascade system using ammonia is also on the agenda according to one of Australia’s leading supermarket refrigeration specialists, Frigrite Refrigeration. “We have traveled the world investigating system design and have developed solutions that best suit the Australian market. We installed the first CO2 systems in Australia, with another four systems installed in new supermarkets since,” says Andrew Reid, national account manager for Frigrite. “Due to economic constraints, the cascade CO2 systems installed in Australia best suit the energy and environmental expectations, however, further development is underway in finding improvements to the current concepts, which may involve a fundamental system design change and alternate refrigerants to those currently being used.” Reid says supermarket chains have acknowledged the importance of meeting environmental and community expectations as the general awareness of these two aspects increases. -

Hypermarket Lessons for New Zealand a Report to the Commerce Commission of New Zealand

Hypermarket lessons for New Zealand A report to the Commerce Commission of New Zealand September 2007 Coriolis Research Ltd. is a strategic market research firm founded in 1997 and based in Auckland, New Zealand. Coriolis primarily works with clients in the food and fast moving consumer goods supply chain, from primary producers to retailers. In addition to working with clients, Coriolis regularly produces reports on current industry topics. The coriolis force, named for French physicist Gaspard Coriolis (1792-1843), may be seen on a large scale in the movement of winds and ocean currents on the rotating earth. It dominates weather patterns, producing the counterclockwise flow observed around low-pressure zones in the Northern Hemisphere and the clockwise flow around such zones in the Southern Hemisphere. It is the result of a centripetal force on a mass moving with a velocity radially outward in a rotating plane. In market research it means understanding the big picture before you get into the details. PO BOX 10 202, Mt. Eden, Auckland 1030, New Zealand Tel: +64 9 623 1848; Fax: +64 9 353 1515; email: [email protected] www.coriolisresearch.com PROJECT BACKGROUND This project has the following background − In June of 2006, Coriolis research published a company newsletter (Chart Watch Q2 2006): − see http://www.coriolisresearch.com/newsletter/coriolis_chartwatch_2006Q2.html − This discussed the planned opening of the first The Warehouse Extra hypermarket in New Zealand; a follow up Part 2 was published following the opening of the store. This newsletter was targeted at our client base (FMCG manufacturers and retailers in New Zealand). -

Supply-Change.Org Company Launch List

Supply-Change.Org Company Launch List Is your company on this list? Contact Supply Change to request a profile preview, now through March 25, 2015. Adani Wilmar Burberry Emami Biotech Adidas Campbell's Etablissements Fr. Colruyt AEON Cargill Eurostar Agropalma Carrefour Farm Frites Ahlstrom Casino Fazer Group Ajinomoto Catalyst Paper Ferrero Trading Aldi Nord Cefetra Findus Group Aldi Sud Cémoi Florin Almacenes Exito Cencosud General Mills Amcor Cérélia Ginsters Arla Foods Coca-Cola Godrej Industries Arnott's Biscuits Coles Supermarkets Golden Agri-Resources ASDA Colgate-Palmolive Goodman Fielder Asia Pacific Resources Compass Group Greenergy International International Limited ConAgra Foods Grupo André Maggi Asia Pulp and Paper Co-op Clean Co. Grupo JD Associated British Foods Coop Norway Gucci Auchan Coop Sweden H & M August Storck Coop Switzerland Hain Celestial Aviko Co-operative Group Haribo Avon CostCo HarperCollins Axfood Cranswick Harry's Barilla CSM Bakery Supplies Hasbro Barry Callebaut Food Dai Nippon Printing Co. Heineken International Manufacturers Europe Dairy Farm International Heinz BASF Danone Henkel Bayer Dansk Supermarked Hershey Company Beijing Hualian Danzer Hewlett-Packard Best Buy Delhaize Hillshire Brands BillerudKorsnäs Doctor's Associates Holmen Bimbo Dohle Handelsgruppe Holding ICA Bongrain Dow IGA Boots UK Drax Group Iglo Foods Group Brambles Dunkin' Brands Igor Novara Brioche Pasquier Cerqueux Dupont Ikea British Airways Ecover Inditex British Sky Broadcasting Elanco International Flavors & Fragrances Bunge -

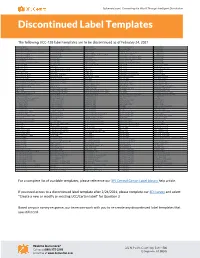

Discontinued Label Templates

3plcentral.com | Connecting the World Through Intelligent Distribution Discontinued Label Templates The following UCC-128 label templates are to be discontinued as of February 24, 2021. AC Moore 10913 Department of Defense 13318 Jet.com 14230 Office Max Retail 6912 Sears RIM 3016 Ace Hardware 1805 Department of Defense 13319 Joann Stores 13117 Officeworks 13521 Sears RIM 3017 Adorama Camera 14525 Designer Eyes 14126 Journeys 11812 Olly Shoes 4515 Sears RIM 3018 Advance Stores Company Incorporated 15231 Dick Smith 13624 Journeys 11813 New York and Company 13114 Sears RIM 3019 Amazon Europe 15225 Dick Smith 13625 Kids R Us 13518 Harris Teeter 13519 Olympia Sports 3305 Sears RIM 3020 Amazon Europe 15226 Disney Parks 2806 Kids R Us 6412 Orchard Brands All Divisions 13651 Sears RIM 3105 Amazon Warehouse 13648 Do It Best 1905 Kmart 5713 Orchard Brands All Divisions 13652 Sears RIM 3206 Anaconda 13626 Do It Best 1906 Kmart Australia 15627 Orchard Supply 1705 Sears RIM 3306 Associated Hygienic Products 12812 Dot Foods 15125 Lamps Plus 13650 Orchard Supply Hardware 13115 Sears RIM 3308 ATTMobility 10012 Dress Barn 13215 Leslies Poolmart 3205 Orgill 12214 Shoe Sensation 13316 ATTMobility 10212 DSW 12912 Lids 12612 Orgill 12215 ShopKo 9916 ATTMobility 10213 Eastern Mountain Sports 13219 Lids 12614 Orgill 12216 Shoppers Drug Mart 4912 Auto Zone 1703 Eastern Mountain Sports 13220 LL Bean 1702 Orgill 12217 Spencers 6513 B and H Photo 5812 eBags 9612 Loblaw 4511 Overwaitea Foods Group 6712 Spencers 7112 Backcountry.com 10712 ELLETT BROTHERS 13514 Loblaw -

2018 Annual Report 1 Overview

Wesfarmers Annual Report Annual Wesfarmers 2018 WESFARMERS ANNUAL REPORT 2018 CONTENTS Overview 2 2018 year in review 4 Primary objective 5 Group structure 6 Performance overview 8 Chairman’s message 10 Managing Director’s report 12 Leadership Team Operating and financial review 14 Operating and financial review 26 Retail businesses 26 Bunnings 32 Coles 40 Department Stores 42 – Kmart 44 – Target 46 Officeworks 50 Industrials 52 – Chemicals, Energy and Fertilisers 54 – Industrial and Safety 56 – Resources 57 Other activities Sustainability 58 Sustainability Governance 66 Board of directors 68 Corporate governance overview Directors’ report 72 Directors’ report 77 – Remuneration report Financial statements About Wesfarmers About this report 97 Financial statements From its origins in 1914 as a Western This annual report is a summary Wesfarmers is committed to reducing Australian farmers’ cooperative, of Wesfarmers and its subsidiary the environmental footprint associated 103 Notes to the financial statements Wesfarmers has grown into one of companies’ operations, activities and with the production of this annual Australia’s largest listed companies. financial performance and position report and printed copies are only Signed reports With headquarters in Perth, its as at 30 June 2018. In this report posted to shareholders who have diverse business operations references to ‘Wesfarmers’, ‘the elected to receive a printed copy. This 145 Directors’ declaration cover: supermarkets, liquor, hotels company’, ‘the Group’, ‘we’, ‘us’ report is printed on environmentally 146 Independent auditor’s report and convenience stores; home and ‘our’ refer to Wesfarmers Limited responsible paper manufactured under improvement; department stores; (ABN 28 008 984 049), unless ISO 14001 environmental standards. -

The Australian Grocery Sector: Structurally Irredeemable?

THE AUSTRALIAN GROCERY SECTOR: structurally irredeemable? Alexandra Merrett and Rhonda L Smith1 By all appearances, the grocery sector in Australia is less than ideally competitive and indeed less competitive than most other advanced economies. It may be that the size of the Australian economy imposes a natural limit on the market structure whereby the available economies of scale and scope mean that there is only room for two large players. The evidence suggests that, while Coles and Woolworths may have substantial market power, they do not take advantage of such market power by systematic monopoly pricing. Rather, any uses of market power are episodic and appear largely related to non-price conduct. Indeed, it seems the biggest impact for Australian consumers of our present market structure is reduced choice and innovation as sources of supply are rationalised. Australians may therefore need to consider the extent to which they prefer increased choice over lower prices and the convenience of one-stop shops. In considering these issues, this paper attempts to assess anecdotal claims – particularly in relation to ‘must have’ brands and private labels – by reference to available data. In doing so, we highlight several potential uses of publicly available information which may go some way to proving or disproving market power problems in the Australian grocery sector. 1 Alexandra Merrett is a competition lawyer and Senior Fellow at the Melbourne Law School, and may be contacted on [email protected]. Rhonda Smith is an economist and Senior Lecturer at the University of Melbourne. She may be contacted on [email protected]. -

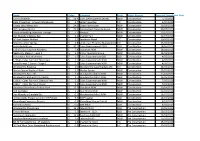

Name Value Company State Status Reason Forecast Completion Date Coles Schofields 34.9 $ Coles Developments (NSW) NSW Constr

Name Value Company State Status Reason Forecast Completion Date Coles Schofields $ 34.9 Coles Developments (NSW) NSW Construction 1/10/2021 Salta Properties - Citiwest Warehouse $ 5.7 Salta Properties VIC Construction 6/09/2021 Costco Lake Macquarie $ 24.6 Costco Wholesale NSW Construction 23/08/2021 262 Liverpool Street $ 25.6 Cornerstone Property Group NSW Construction 30/07/2021 Westrac Building Extension Tomago $ 5.7 Westrac NSW Construction 22/07/2021 Dan Murphy's Bateau Bay $ 2.1 Charter Hall NSW Construction 12/07/2021 BP Fuel Station Wollert $ 2.5 Sandhurst Retail VIC Construction 30/06/2021 Kmart Caroline Springs $ 2.8 Lend Lease Property Management (Australia)VIC Construction P/L 25/06/2021 Coles Andergrove $ 20.2 Coles Developments QLD QLD Construction 18/06/2021 115-151 Dunning Ave Rosebery $ 7.8 Goodman NSW NSW Construction 16/06/2021 Neeta City Stage 2 - Level 1 $ 5.2 Elanor Investors Group NSW Construction 15/06/2021 Coles Ascot Refurbishment $ 1.6 Coles Supermarkets QLD QLD Construction 4/06/2021 1236.8 - Coles Format C Moss Vale $ 2.2 Coles Supermarkets NSW NSW Construction 4/06/2021 Coles Format C Stores - Stage 2 $ 2.3 Coles Supermarkets NSW NSW Construction 4/06/2021 Woolworths Belgrave $ 1.0 Woolworths Supermarkets VIC VIC Construction 28/05/2021 Marley Spoon Wetherill Park $ 1.5 Marley Spoon NSW Construction 25/05/2021 Woolworths Bass Hill $ 2.4 Woolworths (Misc) NSW NSW Construction 21/05/2021 Woolworths Bathurst City Centre $ 1.7 Woolworths (Misc) NSW NSW Construction 13/05/2021 1236.6 - Coles Format C Edensor Park -

Information About Coles Group

6 Information about Coles Group 6.1 Background Information Coles Group (ASX:CGJ) is one of Australia’s largest retailers with approximately 3,000 stores, revenue of $34.7 billion (FY2007) and market capitalisation of approximately $18.0 billion as at 25 September 2007. Coles Group is headquartered in Melbourne, Australia and employs approximately 170,000 people nationally. A brief history of Coles Group is set out below. • The fi rst Coles Group variety store was opened in Melbourne, Victoria in 1914 and the fi rst Coles Group supermarket was opened in 1960. At the end of the 2007 fi nancial year, 674 Coles and 71 Bi-Lo supermarkets were open. • The fi rst Kmart opened in Melbourne, Victoria in 1969, and as at the end of the 2007 fi nancial year, there were 182 Kmart stores in Australia and New Zealand, making it Australia’s largest discount department store operator. • In 1985, Coles Group merged with The Myer Emporium Limited to create Coles Myer Limited. • The merger with the Myer Emporium brought Target into the brand portfolio which, as at the end of the 2007 fi nancial year, had 268 locations in metropolitan and country areas offering on-trend apparel and soft home-wares. • Through the 1980s and 1990s Coles Group acquired a number of liquor businesses and over the past six years it has continued to expand its liquor business by acquiring hotels and rolling out superstores. • In 1994 the fi rst Offi ceworks store opened, with the chain having grown to 107 stores and nine Harris Technology Business Centres as at the end of the 2007 fi nancial year. -

Financial Services Guide and Independent Expert’S Report in Relation to the Proposed Demerger of Coles Group Limited by Wesfarmers Limited

FINANCIAL SERVICES GUIDE AND INDEPENDENT EXPERT’S REPORT IN RELATION TO THE PROPOSED DEMERGER OF COLES GROUP LIMITED BY WESFARMERS LIMITED GRANT SAMUEL & ASSOCIATES PTY LIMITED ABN 28 050 036 372 5 OCTOBER 2018 FINANCIAL SERVICES GUIDE Grant Samuel & Associates Pty Limited (“Grant Samuel”) holds Australian Financial Services Licence No. 240985 authorising it to provide financial product advice on securities and interests in managed investments schemes to wholesale and retail clients. The Corporations Act, 2001 requires Grant Samuel to provide this Financial Services Guide (“FSG”) in connection with its provision of an independent expert’s report (“Report”) which is included in a document (“Disclosure Document”) provided to members by the company or other entity (“Entity”) for which Grant Samuel prepares the Report. Grant Samuel does not accept instructions from retail clients. Grant Samuel provides no financial services directly to retail clients and receives no remuneration from retail clients for financial services. Grant Samuel does not provide any personal retail financial product advice to retail investors nor does it provide market-related advice to retail investors. When providing Reports, Grant Samuel’s client is the Entity to which it provides the Report. Grant Samuel receives its remuneration from the Entity. In respect of the Report for Wesfarmers Limited in relation to proposed demerger of Coles Group Limited (“the Wesfarmers Report”), Grant Samuel will receive a fixed fee of $1.5 million plus reimbursement of out-of-pocket expenses for the preparation of the Report (as stated in Section 8.3 of the Wesfarmers Report). No related body corporate of Grant Samuel, or any of the directors or employees of Grant Samuel or of any of those related bodies or any associate receives any remuneration or other benefit attributable to the preparation and provision of the Wesfarmers Report. -

Fairly Traded Supplier Approval and Management Using Sedex

Fairly Traded Supplier Approval and Management Using Sedex Coles is committed to the responsible manufacture and provision of goods and services. The Coles Ethical Sourcing Policy is based primarily on Ethical Trade Initiative (ETI) and International Labour Organisation (ILO) Conventions. Introduction Coles is utilising the Sedex online portal to manage our Supplier ethical data and approval process. Coles requires all suppliers of Coles Brand, fresh produce, services and goods not for resale to become a ‘B’ member of Sedex and adhere with the approval processes outlined in this document. What is Sedex? - Membership organisation offering an online database which allows members to upload, share, manage and report on ethical information such as labour standards and health and safety policies within their own company and supply chain. - Simple and effective way to view and monitor supplier's data, so customers know where their products are coming from and if their suppliers practise local and international working standards. - Sedex is positively influencing the lives of over 24 Million workers in more than 150 countries. Benefits of Supplier ‘B’ Membership: - Lower admin burden and reduce the loss of production time. - Reduce reputational risk. - Membership cost for a production site is £40.32 for a year (as at April 2016). - Helps reduce the number of ethical audits as members can share information with multiple customers. To find out which of your customers are Sedex members, see http://www.sedexglobal.com/about-sedex/buyers-and-suppliers/list-of-members/ - Efficient and cost effective way of sharing ethical information with multiple customers. 1 Sedex and Coles Fusion Requirements 1.1. -

2019 Annual Report

20 September 2019 The Manager Company Announcements Office Australian Securities Exchange Dear Manager, 2019 ANNUAL REPORT Attached is the Coles Group Limited 2019 Annual Report. A copy of the report will be sent in mid-October 2019 to those shareholders who have elected to receive a copy. The report is also available on the Company’s website www.colesgroup.com.au. Yours faithfully, Daniella Pereira Company Secretary Coles Group Limited ABN 11 004 089 936 800 Toorak Road Hawthorn East Victoria 3123 Australia PO Box 2000 Glen Iris Victoria 3146 Australia Telephone +61 3 9829 5111 www.colesgroup.com.au 2019 Annual Report. Sustainably feed all Australians to help them lead healthier, happier lives. Coles acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of Country throughout Australia and pays its respects to elders past and present. We recognise their rich cultures and continuing connection to land and waters. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are advised that this document may contain names and images of people who are deceased. All references to Indigenous people in this document are intended to include Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people. Contents 3 Welcome to Coles 4 2019 performance 5 2019 highlights 6 Message from the Chairman 8 Managing Director and Chief Executive Officer’s report 12 Our vision, purpose and strategy 14 How we create value 17 Sustainability overview 18 Sustainability highlights 20 Our financial and operating performance 29 Looking to the future 30 How we manage risk 35 Climate change 38 Corporate governance 45 Directors’ report 63 Financial report 104 Shareholder information Forward-looking statements This report contains forward-looking statements in relation to to be correct.