Horizontal Communication and Social Movements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greenwald 1 Dara Greenwald

Dara Greenwald 53 3rd Street | Troy, NY 12180 USA | 773.459.3308 | [email protected] | http://www.daragreenwald.com EDUCATION Ph.D. (ABD) Electronic Arts, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY M.F.A. Electronic Arts, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY, 2007 M.F.A. Writing, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, 2003 B.A. Women’s Studies and Dance, Oberlin College, Oberlin, OH, 1993 Independent coursework in teaching and education, 1993-1998 TEACHING EXPERIENCE 2007-2008 Teaching Assistant, Electronic Arts, RPI, Troy, NY (Art, Community, Technology; Multimedia Century; Advanced Video) 2003–2005 Part-time Faculty, Film/Video/New Media, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL (Microcinema and the Short; Independent Programming and Distribution for Film/Video/New Media) 2002 Instructor of Record, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL (Essay Writing: Personal Narrative) Teaching Assistant to Vanalyn Green, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL (Video History) 1997-98 Founding Teacher, Academy of Communications and Technology, Chicago, IL (Humanities, Media Studies) 1993-95 Teacher, Teach for America/Backus Middle School, Washington, DC (Social Studies, Dance) OTHER RELAVENT EMPLOYMENT 1998-2005 Distribution Manager, Video Data Bank, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL Responsible for all aspects of distribution of artist videos, including: acquisitions, sales, promotions, representing artists and organization at national and international festivals and -

Taking Information to the Street Radical Reference Collective (Shinjoung Yeo, Joel Rane, James R

Radical Reference: taking information to the street Radical Reference Collective (Shinjoung Yeo, Joel Rane, James R. Jacobs, Lia Friedman, Jenna Freedman) Information Outlook, Spring, 2005 (Preprint) Radical Reference (RR) is a volunteer-run collective of library workers (Librarians, support staff, and LIS students) who believe in social justice and equality. RR provides reference service and information access to independent journalists, activists and the general public via its web site and on the street at political events. RR was launched in July, 2004 to assist and support the many activists and the public converging on New York City to protest at the 2004 Republican National Convention (RNC). During the RNC, RR volunteers went out to the streets and provided reference service to out-of- towners, journalists and anyone with a question. This “street reference” was conducted using carefully crafted “ready reference kits” that included maps, transportation information, lists of emergency phone numbers, etc. Teams of home support volunteers were on call for questions that could not be readily answered with the information on hand. Additionally, home support acted as a virtual affinity group by monitoring local mainstream and alternative media to keep street reference informed about various events and police activities. In less than a year, RR has become known in activist communities that recognize the critical role that information professionals play in the movement for social justice. In light of this, RR has expanded its services to include fact-checking workshops and skill- sharing sessions on infoshops, alternative library resources and fact-checking at American Library Association (ALA) conferences. There are future plans for copyright activism sessions at ALA as well as projects as diverse as indexing alternative media resources and creating an image archive for the NY City Independent Media Center (NYCIMC). -

Society Register

ISSN 2544-5502 SOCIETY REGISTER 4 (4) 2020 Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan ISSN 2544-5502 SOCIETY REGISTER 4 (4) 2020 Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan SOCIETY REGISTER 2020 / Vol. 4, No. 4 ISSN: 2544-5502 | DOI: 10.14746/sr EDITORIAL TEAM: Mariusz Baranowski (Editor-in-Chief), Marcos A. Bote (Social Policy Editor), Piotr Cichocki (Quantitative Research Editor), Sławomir Czapnik (Political Science Editor), Piotr Jabkowski (Statistics Editor), Mark D. Juszczak (International Relations), Agnieszka Kanas (Stratification and Inequality Editor), Magdalena Lemańczyk (Anthropology Editor), Urszula Markowska-Manista (Educational Sciences Editor), Bartosz Mika (Sociology of Work Editor), Kamalini Mukherjee (English language Editor), Krzysztof Nowak-Posadzy (Philoso- phy Editor), Anna Odrowąż-Coates (Deputy Editor-in-Chief), Aneta Piektut (Migration Editor). POLISH EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS: Agnieszka Gromkowska-Melosik, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań (Poland); Kazimierz Krzysztofek, SWPS University of Social Sciences and Humanities (Poland); Roman Leppert, Kazimierz Wielki University (Poland); Renata Nowakowska-Siuta, ChAT (Poland); Inetta Nowosad, University of Zielona Góra (Poland); Ewa Przybylska, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń (Poland); Piotr Sałustowicz, SWPS University of Social Sciences and Humanities (Poland); Bogusław Śliwerski, University of Lodz (Poland); Aldona Żurek, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań (Poland). INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS: Tony Blackshaw, Sheffield Hallam University (United King- dom); Theodore Chadjipadelis, Aristotle University Thessaloniki (Greece); Kathleen J. Farkas, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio (US); Sribas Goswami, Serampore College, University of Calcutta (India); Bozena Hautaniemi, Stockholm University (Sweden); Kamel Lahmar, University of Sétif 2 (Algeria); Georg Kam- phausen, University of Bayreuth (Germany); Nina Michalikova, University of Central Oklahoma (US); Jaroslaw Richard Romaniuk, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio (US); E. -

Information Outlook, June 2005

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Information Outlook, 2005 Information Outlook, 2000s 6-2005 Information Outlook, June 2005 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_io_2005 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Information Outlook, June 2005" (2005). Information Outlook, 2005. 6. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_io_2005/6 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Information Outlook, 2000s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Information Outlook, 2005 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. vol. 9, no. 6 June 2005 www.sla.org ACS PUBLICATIONS Partnering with librarians worldwide to advance the chemical enterprise Since 1879, ACS Publications has achieved unparalleled excellence in the chemical sciences. Such achievement is due to the dedication of information specialists worldwide who advance the chemical enterprise by providing access to the scientists they serve. Librarians like you. access | insight | discovery http://pubs.acs.org Librarian Optical engineer Laser physicist Lab technician Never underestimate the importance of a librarian. Okay, chances are you won’t actually find a librarian firing a high-energy laser. But librarians do play a vital role on any engineering team, enabling research breakthroughs and real-time solutions. Whether you’re selecting information for research communities or decision support for professionals, Elsevier provides access to the highest quality scientific, technical and health information in multiple media, including innovative electronic products like ScienceDirect® and MD Consult. -

Perspectives on Anarchist Theory

Contents Spring 1998 The Institute for IAS Update Anarchist Studies Being a Radical Professor Radical Cities and Social Revolution: An Interview with Janet Biehl The abstractness and programmatic emptiness so ian municipalism calls for the creation of self- characteristic of contemporary radical theory managed community political life at the municipal indicates a severe crisis in the left. It suggests a level: the level of the village, town, neighborhood, retreat from the belief that the ideal of a or small city. This political life would be embodied cooperative, egalitarian society can be made in institutions of direct democracy: citizens' assem concrete and thus realized in actual social blies, popular assemblies, or town meetings. Where relationships. It is as though - in a period of change such institutions already exist, their democratic and demobilization - many radicals have ceded the potential and structural power could be enlarged; right and the capacity to transform society to where they formerly existed, they could be revived; CEO's and heads of state. and where they never existed, they could be created Janet BiehFs new book, The Politics of Social anew. But within these institutions people as Ecology: Libertarian Municipalism, is an affront to citizens could manage the affairs of their own this. It challenges the politically resigned with a communities themselves - rather than relying on detailed, historically situated anti-statist and anti- statist elites - arriving at policy decisions through capitalist politics for today. the processes of direct democracy. I asked Biehl about her new work in the fall of To address problems that transcend the bound 1 9 9 7 b y e m a i l . -

International Medical Corps Afghanistan

Heading Folder Afghanistan Afghanistan - Afghan Information Centre Afghanistan - International Medical Corps Afghanistan - Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan (RAWA) Agorist Institute Albee, Edward Alianza Federal de Pueblos Libres American Economic Association American Economic Society American Fund for Public Service, Inc. American Independent Party American Party (1897) American Political Science Association (APSA) American Social History Project American Spectator American Writer's Congress, New York City, October 9-12, 1981 Americans for Democratic Action Americans for Democratic Action - Students for Democractic Action Anarchism Anarchism - A Distribution Anarchism - Abad De Santillan, Diego Anarchism - Abbey, Edward Anarchism - Abolafia, Louis Anarchism - ABRUPT Anarchism - Acharya, M. P. T. Anarchism - ACRATA Anarchism - Action Resource Guide (ARG) Anarchism - Addresses Anarchism - Affinity Group of Evolutionary Anarchists Anarchism - Africa Anarchism - Aftershock Alliance Anarchism - Against Sleep and Nightmare Anarchism - Agitazione, Ancona, Italy Anarchism - AK Press Anarchism - Albertini, Henry (Enrico) Anarchism - Aldred, Guy Anarchism - Alliance for Anarchist Determination, The (TAFAD) Anarchism - Alliance Ouvriere Anarchiste Anarchism - Altgeld Centenary Committee of Illinois Anarchism - Altgeld, John P. Anarchism - Amateur Press Association Anarchism - American Anarchist Federated Commune Soviets Anarchism - American Federation of Anarchists Anarchism - American Freethought Tract Society Anarchism - Anarchist -

Autumn Winters. the Infoshop As a Community Information Resource: a Study of Internationalist Books

Autumn Winters. The Infoshop as a Community Information Resource: A Study of Internationalist Books. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S. Degree. May 2001. 62 pages. Advisor: David Carr. This study describes a telephone survey of members of the Internationalist Books collective and an analysis of periodical holdings at Internationalist Books, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Chapel Hill Public Library. The study was conducted to examine the community services and functions performed by infoshops, as compared to those performed by academic and public libraries. Twenty-three collective members were surveyed about their support of Internationalist Books. Survey results indicate that Internationalist Books has a high standing in this community, despite frequent financial and organizational crises. The analysis of holdings was meant to examine the collection of periodicals indexed in Alternative Press Index by local libraries and by Internationalist Books. Results indicated that Internationalist Books is an important source of alternative periodicals, second only to the university library. Headings: Infoshops Alternative Press Index Bookstores – North Carolina Special Collections – Special Subjects – Underground Literature THE INFOSHOP AS A COMMUNITY INFORMATION RESOURCE: A STUDY OF INTERNATIONALIST BOOKS by Autumn Winters A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina May, 2001 Approved by: ____________________ Advisor 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. David Carr, who served as my advisor for this study. -

Of Class War and Crimethinc

Journal of Political Ideologies ISSN: 1356-9317 (Print) 1469-9613 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cjpi20 The ‘punk anarchisms’ of Class War and CrimethInc. Jim Donaghey To cite this article: Jim Donaghey (2020) The ‘punk anarchisms’ of Class War and CrimethInc., Journal of Political Ideologies, 25:2, 113-138, DOI: 10.1080/13569317.2020.1750761 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2020.1750761 Published online: 20 Apr 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 125 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cjpi20 JOURNAL OF POLITICAL IDEOLOGIES 2020, VOL. 25, NO. 2, 113–138 https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2020.1750761 The ‘punk anarchisms’ of Class War and CrimethInc. Jim Donaghey School of History, Anthropology, Philosophy and Politics, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast, Northern Ireland ABSTRACT Many of the connections between punk and anarchism are well recognized (albeit with some important contentions). This recogni- tion is usually focussed on how punk bands and scenes express anarchist political philosophies or anarchistic praxes, while much less attention is paid to expressions of ‘punk’ by anarchist activist groups. This article addresses this apparent gap by exploring the ‘punk anarchisms’ of two of the most prominent and influential activist groups of recent decades (in English-speaking contexts at least), Class War and CrimethInc. Their distinct, yet overlapping, political approaches are compared and contrasted, and in doing so, pervasive assumptions about the relationship between punk and anarchism are challenged, refuting the supposed dichotomy between ‘lifestylist’ anarchism and ‘workerist’ anarchism. -

TEDROW-DISSERTATION-2015.Pdf

Copyright by Matthew Allen Tedrow 2015 The Dissertation Committee for Matthew Allen Tedrow certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Black Sails on the Mediascape: Towards an Anarchist Theory of News Media and Media-Movement Interactions Committee: Russell Todd, Supervisor Mercedes de Uriarte, Co-Supervisor Mary Bock Gene Burd Robert Jensen Michael Young Black Sails on the Mediascape: Towards an Anarchist Theory of News Media and Media-Movement Interactions by Matthew Allen Tedrow, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2015 Dedication For Breanna. Acknowledgements Dozens of people deserve thanks for helping me finish this dissertation. Foremost among these are the UT-Austin faculty members who served on my dissertation committee. As a confidant, mentor, and advocate, Mercedes de Uriarte guided me through the process from start to finish. She gave me expert, critical feedback on every chapter, and although I did not incorporate all of her suggested edits, this work bears her imprint. Gene Burd, who chaired my committee until retiring in 2014, impressed upon me the significance of “messy,” qualitative methods and heterodox research interests. I have spent hundreds of hours in conversation with Mercedes and Gene, who have shaped my views on academic integrity, the power of news media, the history of U.S. radicalism, and the political economy of journalism research and education. I owe them an enormous intellectual debt, and am grateful for their generosity and friendship. -

Beyond the Co-Op Wall: Connecting with Local Communities

NASCO INSTITUTE 2004 A Co-operative Education & Training Institute Beyond the Co-op Wall: Connecting With Local Communities November 5 - 7, 2004 in Ann Arbor, Michigan Beyond the Co-op Wall: Connecting With Local Communities Perhaps the most incredible facet of our co-ops is the deliberate energy and care that we invest into improving the structure and community of our homes and workplaces. Unfortunately, the trend over the years has been that such improvements become so focused on ourselves that we fail to invest our refined skill and service back into our neighborhoods. This year’s Institute challenges us to go beyond the ‘co-op wall’ that we often create, and rarely recognize, to translate our concern for community into action. The weekend’s courses will discern the cultural barriers that sometimes separate co-ops from their local communities, and explore some of the ways in which we can be an active part of improving our surrounding environment through volunteerism, social action, coalition building, and local co-operation. The theme builds on recent efforts within NASCO to take an honest look at dynamics of power and privilege in our co-ops, by expanding issues of equity and inclusion to a broader context. NASCO’s Cooperative Education and Training Institute The NASCO Institute is widely recognized as one of the best training and networking opportunities available for co-opers and has provided cooperative training for 27 consecutive years! Institute participants describe the conference as a source of inspiration and a chance to gain valuable knowledge and skills. Over 400 participants from all over Canada, the United States, and beyond descend on Ann Arbor every fall to share ideas, learn new skills, and look at issues affecting the cooperative movement. -

“Unless You're a Self-Advocate, You Fall Through the Cracks.”

ONE TIME ONLY: FALL 2015/WINTER 2016 Stories, information and fact sheets for health and wellness PLUS 12 PAGES OF RESOURCES— FROM BOOKS TO PEN PALS ALL FOR PEOPLE IN PRISON “Unless you’re a self-advocate, you fall through the cracks.” p. 14, Feature story Kerry Thomas, incarcerated in Idaho IIIIIIIIIIIfrom the Publisher IIIIIIIIIIIfrom the EDITORS ’ve been living with HIV since before the virus was discovered. Back then, Dear Reader, people were afraid to touch us, funeral homes wouldn’t accept the bodies of our dead, families wouldn’t let their children in the door, or served us A One-Time Only Publication TURN IT UP! is for people in prison, and many of the I for Incarcerated People food on disposable plates. The word “stigma” barely conveys how that felt. Single issue: Fall 2015/Winter 2016 people who created TURN IT UP! have served time Fighting for our lives, we demanded dignity. We organized for our behind the walls, fighting to stay healthy despite the right to participate in our own medical care and in the decisions and poli- Laura Whitehorn and Suzy Subways, Editors-in-Chief many obstacles prison presents. We have experienced cies that would profoundly affect our lives. In June 1983, a group of people Cindy Stine, Project Manager discrimination (from eye-rolling, to being denied hous- with AIDS wrote the Denver Principles: Andrea Piccolo, Art Director ing, jobs, and other basic human rights) because of our Susie Day, Copy Editor “We condemn attempts to label us as ‘victims,’ a term which implies Cover art by Corina Dross prison records, race, HIV status, sexuality or gender. -

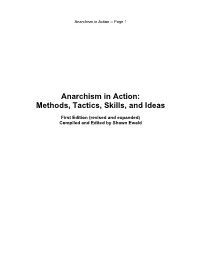

Anarchism in Action -- Page 1

Anarchism in Action -- Page 1 Anarchism in Action: Methods, Tactics, Skills, and Ideas First Edition (revised and expanded) Compiled and Edited by Shawn Ewald Anarchism in Action -- Page 2 Table of Contents Introduction Forms of Decision Making and Organization Direct Democracy Consensus Affinity Groups Collectives Federations and Networks Communication: Getting the Word Out Postering, Tabling, and Propaganda Distribution Tips on Giving Speeches and Presentations Traditional Alternative media Microradio The Internet and Independent Media Mainstream press relations Organizing and Action Types of Organizing Community Organizing Labor Organizing Student Organizing Building Coalitions Types of Actions Protests Strikes and Labor Actions Le Tute Bianche, W.O.M.B.L.E.S., Black Blocs, and Police Confrontation Monkeywrenching Squatting as a Protest Tactic Rooftop Occupations Hunger Strikes Street Parties and Street Theater Billboard Improvement Jail Solidarity Security, Protection, and Self-Defense Security Practices and Security Culture Police Tactics and Your Legal Rights Legal Observers Action Reconnaissance and Scouting Basic First Aid and Street Medics Physical Self-Defense Anarchism in Action -- Page 3 (Table of Contents continued) Anarchist Projects Social Centers, Community Spaces, and Squats Infoshops Microradio Stations Mutual Aid Projects Tenant's Unions Free Schools IWW and IWA Food Not Bombs Homes Not Jails Anti-Racist Action Copwatch Earth First! ACT UP Reclaim The Streets Fundraising and Non-Profit Organizations Fundraising Activities Grant Proposal Writing and Foundation Funding Starting an unincorporated association or non-profit References and Recommended Reading Anarchism in Action -- Page 4 Introduction "Now you ask me how you could help this movement or what you could do, and I have no hesitation in saying, much.