Commentary John F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USS Midway History

USS Midway History The ship you will be visiting on your field trip is called the USS Midway. Did you ever wonder how it got its name? First of all, every Navy ship in the United States has a name beginning with USS, which stands for United States Ship. Midway was the name of an important battle in World War II. That’s why the Navy chose Midway for the name of this ship. One of the first things you will notice when you arrive at the Midway is the large 41 painted on the side of the ship. What could that mean? Well, the Navy numbers its ships in order, as they are built. The very first aircraft carrier ever built in the United States was the USS Langley, built in 1922. It was number 1. The Midway, built in 1945, was number 41. The newest carrier now in use is the USS George H. W. Bush, number 77. The next thing you will notice about the Midway when you drive up close to her is her size. She is HUGE! She is 1,001 feet long, which is about the length of 3 football fields. She is as high as a 20-story building. And, she weighs almost 70,000 tons! That means she weighs about as much as 14,000 elephants or about the same as 6,000 school buses. The Midway could carry up to 80 planes. She has 3 elevators that were used to move planes from the flight deck to inside the ship. Each of these elevators could carry 110,000 pounds. -

Sea Cadet Quarterly

Alum Honoring What’s Inside Achieves Our Fallen Dream p. 5 Heroes pp. 6-9 Courtesy of Lt. Andrew Hrynkiw, USN Jeff Denlea U.S. Naval Sea Cadet Corps Volume 1, Issue 3, December 2014 Sea Cadet Quarterly INST Loretto Polachek, NSCC Loretto INST Cadets Honor Fallen SEALs By Petty Officer 1st Class Michael Nix, NSCC Centurion Battalion, Winter Park, Fla. “Nix, it’s time to wake up.” I look at my watch. It’s 4:20 a.m. to where everyone was gathering. People moved in the dark as Most, if not all, other teenagers would be sound asleep this early shadows, some with flashlights, others without. We needed to on a Sunday morning, but I decided to join the Sea Cadet program have everyone formed up and ready in just 20 minutes so they three years ago. Guess I’m not most teenagers. could grab a quick snack before going to their stations for the This weekend had been a rough couple of days for every petty ceremony. Over 70 cadets from seven different battalions all woke officer who was attending the 2014 UDT-SEAL Museum’s annual up at the same time. We were now forming up in our positions for SEAL Muster. I rolled over in my rack and fumbled for my boots. the ceremony. I shouted the order for squad leaders to take their I’m not sure how I managed to get fully dressed, but I stumbled cadets to the desired locations. outside to where the watch was standing and a couple of the other Finally, the time came for the ceremony to begin. -

South Carolina Naval Wreck Survey Completed James D

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Archaeology and Anthropology, South Carolina Faculty & Staff ubP lications Institute of 3-2005 South Carolina Naval Wreck Survey Completed James D. Spirek University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Christopher F. Amer University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sciaa_staffpub Part of the Anthropology Commons Publication Info Published in Legacy, Volume 9, Issue 1-2, 2005, pages 29-31. http://www.cas.sc.edu/sciaa/ © 2005 by The outhS Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology This Article is brought to you by the Archaeology and Anthropology, South Carolina Institute of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty & Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. South Carolina Naval Wreck Survey Completed By James Spirek and Christopher F. Amer Among the countless wrecked and results of watercraft in South Carolina waters the project. lies a body of naval vessels spanning The project the years from the American Revolu was conducted South Carolina tion to modern times. The manage in two phases. ment of these sunken naval vessels in The first phase State waters and throughout the focused on world falls under the responsibility gathering of the Department of the Navy historical, Range of USN Shipwrecks in SC \.'Vaters (DoN), with the Underwater Archae archaeological, Chariesto,, ector ology Branch of the Naval Historical and environ Center (NHC) as the main arbiter of mental informa issues affecting these cultural tion concerning resources. -

OCTOBER 2016 Volume:5 No:10

The Navy League of Australia - Victoria Division Incorporating Tasmania NEWSLETTER OCTOBER 2016 Volume:5 No:10 OCTOBER “The maintenance of the maritime well-being of the nation” NAVAL HISTORY is the The month of October, in terms of Naval History, is indeed an interesting principal period. Some of the more memorable events spread over previous years objective of are listed in the following:- the Navy League OCTOBER 1805 of Australia England’s victory at The Battle of Trafalgar – 211 years ago on the 21st October 1805, Admiral Lord Nelson defeated a combined Spanish-French Fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar. OCTOBER 1944 The Bathurst Class Minesweeper-Corvette H.M.A.S. Geelong, a sister ship to H.M.A.S. Castlemaine was sunk in a collision with the U.S. Tanker “York” off New Guinea on the 18th October 1944. Patron: Fortunately there was no loss of life in this incident. Governor of Victoria OCTOBER 1944 ____________________ In October 1944 at the Battle of “Leyte Gulf” the following R.A.N. ships engaged, H.M.A.S ‘s Australia, Shropshire, Arunta, Warramunga, Manoora, Kanimbla, Westralia, Gascoyne and H.D.M.L. No.1074. President: During the Battle of Leyte Gulf, a kamikaze Aichi 99 dive bomber crashed LCDR Roger Blythman into the foremast of H.M.A.S. Australia killing 30 Officers and ratings, RANR RFD RET’D including H.M.A.S. Australia’s Commanding Officer Captain E.F.V. Dechaineux. There were also 64 Officers and men wounded in this attack including Commodore J.A. Collins RAN. Snr Vice President: Frank McCarthy . -

Remarks to the Crew of the U.S.S. George Washington in Portsmouth, United Kingdom June 5, 1994

Administration of William J. Clinton, 1994 / June 5 America. And that's why Congress must and will more and more and more than any other part ratify the world trade agreement soon. of our budget, not for new health care but to When we create these good export jobs, we pay more for the same health care. As you must make sure our people are ready to fill know, I am fighting hard to guarantee health them. These days, what you earn depends on care for every American in a way that can never what you learn. Skills and knowledge are the be taken away but that will bring costs in line most important asset of all. That's why we're with inflation. working on a lifetime learning system to train So there's still a lot more to do. But let's every citizen from the first day of preschool be proud of what Americans have done. America to the last day before retirement. is going back to work. Unemployment is down. Now we have to fix our broken unemploy- Jobs are up. Inflation is down. Growth and new ment system to replace it with a reemployment business is up. Our economy is clearly leading system so that when someone loses a job, he the world. We've made this world better by or she can find a good new job as quickly as making the tough choices. That's what we've possible. I am fighting for Congress to pass this got to keep doing. reemployment act this year, too. -

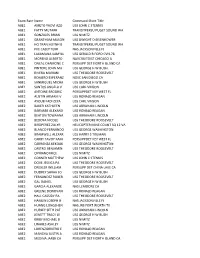

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE1 FATTY MUTARR TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 GONZALES BRIAN USS NIMITZ ABE1 GRANTHAM MASON USS DWIGHT D EISENHOWER ABE1 HO TRAN HUYNH B TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 IVIE CASEY TERR NAS JACKSONVILLE FL ABE1 LAXAMANA KAMYLL USS GERALD R FORD CVN-78 ABE1 MORENO ALBERTO NAVCRUITDIST CHICAGO IL ABE1 ONEAL CHAMONE C PERSUPP DET NORTH ISLAND CA ABE1 PINTORE JOHN MA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 RIVERA MARIANI USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE1 ROMERO ESPERANZ NOSC SAN DIEGO CA ABE1 SANMIGUEL MICHA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 SANTOS ANGELA V USS CARL VINSON ABE2 ANTOINE BRODRIC PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 AUSTIN ARMANI V USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 AYOUB FADI ZEYA USS CARL VINSON ABE2 BAKER KATHLEEN USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BARNABE ALEXAND USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 BEATON TOWAANA USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BEDOYA NICOLE USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 BIRDPEREZ ZULYR HELICOPTER MINE COUNT SQ 12 VA ABE2 BLANCO FERNANDO USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 BRAMWELL ALEXAR USS HARRY S TRUMAN ABE2 CARBY TAVOY KAM PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 CARRANZA KEKOAK USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 CASTRO BENJAMIN USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 CIPRIANO IRICE USS NIMITZ ABE2 CONNER MATTHEW USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE2 DOVE JESSICA PA USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 DREXLER WILLIAM PERSUPP DET CHINA LAKE CA ABE2 DUDREY SARAH JO USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 FERNANDEZ ROBER USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 GAL DANIEL USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 GARCIA ALEXANDE NAS LEMOORE CA ABE2 GREENE DONOVAN USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 HALL CASSIDY RA USS THEODORE -

Navy and Coast Guard Ships Associated with Service in Vietnam and Exposure to Herbicide Agents

Navy and Coast Guard Ships Associated with Service in Vietnam and Exposure to Herbicide Agents Background This ships list is intended to provide VA regional offices with a resource for determining whether a particular US Navy or Coast Guard Veteran of the Vietnam era is eligible for the presumption of Agent Orange herbicide exposure based on operations of the Veteran’s ship. According to 38 CFR § 3.307(a)(6)(iii), eligibility for the presumption of Agent Orange exposure requires that a Veteran’s military service involved “duty or visitation in the Republic of Vietnam” between January 9, 1962 and May 7, 1975. This includes service within the country of Vietnam itself or aboard a ship that operated on the inland waterways of Vietnam. However, this does not include service aboard a large ocean- going ship that operated only on the offshore waters of Vietnam, unless evidence shows that a Veteran went ashore. Inland waterways include rivers, canals, estuaries, and deltas. They do not include open deep-water bays and harbors such as those at Da Nang Harbor, Qui Nhon Bay Harbor, Nha Trang Harbor, Cam Ranh Bay Harbor, Vung Tau Harbor, or Ganh Rai Bay. These are considered to be part of the offshore waters of Vietnam because of their deep-water anchorage capabilities and open access to the South China Sea. In order to promote consistent application of the term “inland waterways”, VA has determined that Ganh Rai Bay and Qui Nhon Bay Harbor are no longer considered to be inland waterways, but rather are considered open water bays. -

Happy25th,GW! on the Cover: (July 4, 1992) Friends and Family Members Gather for the Commission Ceremony of the Aircraft Carrier USS George Washington (CVN 73)

THE ASHINGTON URVEYOR W S JULY 5, 2017 By USS George Washington Public Affairs HAPPY25th,GW! On the cover: (July 4, 1992) Friends and family members gather for the commission ceremony of the aircraft carrier USS George Washington (CVN 73). PHOTO of the of DAY (July 4, 1992) Former First Lady Barbara Bush, the ship’s sponsor, stands with Capt. Robert Nutwell, center, the first commanding officer of the aircraft carrier USS George Washington (CVN 73), during the commissioning ceremony of Washington. The Washington Surveyor Commanding Officer Executive Officer Command Master Chief CAPT Glenn Jamison CDR Colin Day CMDCM James Tocorzic Public Affairs Officer Deputy PAO Media DLCPO Media LPO LCDR Gregory L. Flores LTJG Andrew Bertucci MCC Mary Popejoy MC1 Alan Gragg Editors Staff MC2 Jennifer O’Rourke MC2 Alora Blosch MC3 Devin Bowser MC3 Shayla Hamilton MCSN Marlan Sawyer MC3 Kashif Basharat MC2 Jessica Gomez MC3 Carter Denton MC3 Alan Lewis MCSN Kristen Yarber MC2 Kris R. Lindstrom MC3 Joshua DuFrane MC3 Anna Van Nuys MCSA Julie Vujevich MC2 Bryan Mai MC3 Jacob Goff MC3 Brian Sipe MC2 Jules Stobaugh MC3 Jamin Gordon MCSN Oscar Moreno The Washington Surveyor is an authorized publication for Sailors serving aboard USS George Washington (CVN 73). Contents herein are not the visions of, or endorsed by the U.S. government, the Department of Defense, the Department of the Navy or the Commanding Officer of USS George Washington. All news releases, photos or information for publication in The Washington Surveyor must be submitted to the Public Affairs Officer (7726). *For comments and concerns regarding The Washington Surveyor, email the editor at [email protected]* 25YEARS YOUNGBy MC3 Carter Denton U.S. -

Department of the Navy, Dod § 706.2

Department of the Navy, DoD § 706.2 § 706.2 Certifications of the Secretary TABLE ONE—Continued of the Navy under Executive Order Distance in 11964 and 33 U.S.C. 1605. meters of The Secretary of the Navy hereby forward masthead finds and certifies that each vessel list- Vessel Number light below ed in this section is a naval vessel of minimum required special construction or purpose, and height. that, with respect to the position of § 2(a)(i) Annex I the navigational lights listed in this section, it is not possible to comply USS SAMUEL B. ROBERTS ........ FFG 58 1.6 fully with the requirements of the pro- USS KAUFFMAN ........................... FFG 59 1.6 USS RODNEY M. DAVIS .............. FFG 60 1.6 visions enumerated in the Inter- USS INGRAHAM ........................... FFG 61 1.37 national Regulations for Preventing USS FREEDOM ............................ LCS 1 5.99 Collisions at Sea, 1972, without inter- USS INDEPENDENCE .................. LCS 2 4.14 USS FORT WORTH ...................... LCS 3 5.965 fering with the special function of the USS CORONADO ......................... LCS 4 4.20 vessel. The Secretary of the Navy fur- USS MILWAUKEE ......................... LCS 5 6.75 ther finds and certifies that the naviga- USS JACKSON ............................. LCS 6 4.91 USS DETROIT ............................... LCS 7 6.80 tional lights in this section are in the USS MONTGOMERY .................... LCS 8 4.91 closest possible compliance with the USS LITTLE ROCK ....................... LCS 9 6.0 applicable provisions of the Inter- USS GABRIELLE GIFFORDS ....... LCS 10 4.91 national Regulations for Preventing USS SIOUX CITY .......................... LCS 11 5.98 USS OMAHA ................................. LCS 12 4.27 Collisions at Sea, 1972. -

Naval Accidents 1945-1988, Neptune Papers No. 3

-- Neptune Papers -- Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945 - 1988 by William M. Arkin and Joshua Handler Greenpeace/Institute for Policy Studies Washington, D.C. June 1989 Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945-1988 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Nuclear Weapons Accidents......................................................................................................... 3 Nuclear Reactor Accidents ........................................................................................................... 7 Submarine Accidents .................................................................................................................... 9 Dangers of Routine Naval Operations....................................................................................... 12 Chronology of Naval Accidents: 1945 - 1988........................................................................... 16 Appendix A: Sources and Acknowledgements........................................................................ 73 Appendix B: U.S. Ship Type Abbreviations ............................................................................ 76 Table 1: Number of Ships by Type Involved in Accidents, 1945 - 1988................................ 78 Table 2: Naval Accidents by Type -

Theodore J. Smith U.S

1 Theodore J. Smith U.S. Navy USS Spangler, Pacific Theatre convoy Task Unit 116.15.3 as the flagship of Commander, Escort Division 39 and head for Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides Islands. By mid- February we were escorting Alnitah (AK-127) to Bougainville and rounded out the month patrol- ling off Treasury Island. We escorted convoys of men and materials to Guadalcanal, New Caledo- nia, Florida Island, Majuro, Emirau, Rendova and Manus. In late May, 1944, we sailed from Tulagi to the Admiralty Islands with a supply of hedge- hog depth charges and delivered them to the USS England DE 635, the Raby DE698 and the George DE 697. The next day we rendezvoused with these ships, and the Hazelwood DD 531 and, together we steamed north to Hoggatt Bay. Making contact on a Japanese submarine, my ship and the England went to the attack, but were not successful. During the night, we lost contact with the enemy. After a few hours, the Japanese commanding officer obligingly sur- faced between the Raby and the George and switched on its searchlights. My ship attacked Theodore J. Smith with 24 depth charges, but without success. The U.S. Navy England’s depth charges brought about a huge USS Spangler, Pacific Theatre explosion and a watery grave for the Japanese sub. I went to the draft board and enlisted on my After an overhaul of my ship in late Sep- 18th birthday, May 3, 1943. After boot camp at tember, 1944, we operated out of Purvis Bay on Great Lakes, Illinois, I was sent to the Naval Train- escort assignments and anti-submarine warfare. -

Mount Baker's

ample of the quality 4borhoods of Excellent- story Page 8.) DECEMBER 1994 NUMBER 932 x NAVY LIFE OPERATIONS 4 CNO views ‘90s Navy 16 Operation Restore Democracy 8 Turning housing into homes 18 Seabees divers “can do” 25 Kincaid Sailors impact fleet 26 Forward presence: Exercise Native.’@y “I II 32 East meets West in Bahrain I ’1 34 Joint ops: They don’t just happen 12 Telemedicine PEOPLE CAREER 38 Commongoals 24Rating merger update 42 Seabees build friendships in Caribbean 2 CHARTHOUSE 22 TAFFRAILTALK 46 BEARINGS 44 HEALTH AND SAFETY 48 SHIPMATES On the Covers Front cover: HM1 Manuel Micu of Alameda, Calif., measures out dry goods being providedto citizens of Las Calderas, Dominican Republic. (Photoby JO1 (SW/AW) Randy Navaroli) Back cover: MR3 Greg L. Funk, from Garrett Springs, Kan., turns down a piece of carbon steel in the machine shop aboardUSS Cape Cod (AD 43). (Photo by JO1 Ray Mooney) II Charthouse i 2 ALL HANDS I NOVEMBER 1994 a CNO gives view of ‘90s Navy Pay, housing, medical care top Boorda’s Ijst of prioltties Editor’s Note: All Hands photojournalist J02(AW) Michael Boorda: I am a strong believer in OPTEMPO and PERSTEM- Hart recently interviewed Chiefof Naval OperationsADM Mike PO standards and limiting deployment lengthsto six months Boorda. The CNO discussed a wide range of topics relating or less. Six-month deployments and reasonable PERSTEM- to today‘s Navyand the future of the fleet - subjects impor- PO are not just humanitarian or social concerns, they’re also tant to Sailors everywhere. readiness concerns. We simply can’t deploy people too of- ten ortoo long, or our most important ingredientto sustained AH: Do you foresee any changesto deployment lengths readiness, our best Sailors, won’t stay in the Navy.