04 V 33 2 2018.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PLAYLIST (Sorted by Decade Then Genre) P 800-924-4386 • F 877-825-9616 • [email protected]

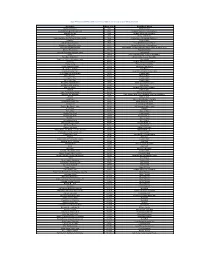

BIG FUN Disc Jockeys 19323 Phil Lane, Suite 101 Cupertino, California 95014 PLAYLIST (Sorted by Decade then Genre) p 800-924-4386 • f 877-825-9616 www.bigfundj.com • [email protected] Wonderful World Armstrong, Louis 1940s Big Band Young at Heart Durante, Jimmy April in Paris Basie, Count Begin the Beguine Shaw, Artie 1960s Motown Chattanooga Choo-Choo Miller, Glenn ABC Jackson 5 Cherokee Barnet, Charlie ABC/I Want You Back - BIG FUN Ultimix Edit Jackson 5 Flying Home Hampton, Lionel Ain't No Mountain High Enough Gaye, Marvin & Tammi Terrell Frenesi Shaw, Artie Ain't Too Proud to Beg Temptations I'm in the Mood for Love Dorsey, Tommy Baby Love Ross, Diana & the Supremes I've Got My Love to Keep Me Warm Brown, Les Chain of Fools Franklin, Aretha In the Mood Miller, Glenn Cruisin' - Extended Mix Robinson, Smokey & the Miracles King Porter Stomp Goodman, Benny Dancing in the Street Reeves, Martha Little Brown Jug Miller, Glenn Got To Give It Up Gaye, Marvin Moonlight Serenade Miller, Glenn How Sweet it Is Gaye, Marvin One O'Clock Jump Basie, Count I Can't Help Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch) - Four Tops, The Pennsylvania 6-5000 Miller, Glenn IDrum Can't MixHelp Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch) Four Tops, The Perdido - BIG FUN Edit Ellington, Duke I Heard it Through the Grapevine Gaye, Marvin Satin Doll Ellington, Duke I Second That Emotion Robinson, Smokey & the Miracles Sentimental Journey Brown, Les I Want You Back Jackson 5 Sing, Sing, Sing - BIG FUN Edit Goodman, Benny (Love is Like a) Heatwave Reeves, Martha Song of India Dorsey, Tommy -

Indian Journal of Comparative Literature and Translation Studies

ISSN 2321-8274 Indian Journal of Comparative Literature and Translation Studies Volume 1, Number 1 September, 2013 Editors Mrinmoy Pramanick Md. Intaj Ali Published By IJCLTS is an online open access journal published by Mrinmoy Pramanick Md. Intaj Ali And this journal is available at https://sites.google.com/site/indjournalofclts/home Copy Right: Editors reserve all the rights for further publication. These papers cannot be published further in any form without editors’ written permission. Advisory Committee Prof. Avadhesh Kumar Singh, Director, School of Translation Studies and Training, Indira Gandhi National Open University, New Delhi Prof Tutun Mukherjee, Professor, Centre for Comparative Literature, University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh Editor Mrinmoy Pramanick Md. Intaj Ali Co-Editor Rindon Kundu Saswati Saha Nisha Kutty Board of Editors (Board of Editors includes Editors and Co-Editors) -Dr. Ami U Upadhyay, Professor of English, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Open University, Ahamedabad, India - Dr. Rabindranath Sarma, Associate Professor, Centre for Tribal Folk Lore, Language and Literature, Central University of Jharkhand, India - Dr. Ujjwal Jana, Assistant Professor of English and Comparative Literature, Pondicherry University, India - Dr. Sarbojit Biswas, Assitant Professor of English, Borjora College, Bankura, India and Visiting Research Fellow, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia - Dr. Hashik N K, Assistant Professor, Department of Cultural Studies, Tezpur University, India - Dr. K. V. Ragupathi, Assistant Professor, English, Central University of Tamilnadu, India - Dr. Neha Arora, Assistant Professor of English, Central University of Rajasthan, India - Mr. Amit Soni, Assistant Professor, Department of Tribal Arts, Indira Gandhi National Tribal University, Amarkantak, M.P., India AND Vice-President, Museums Association of India (MAI) - Mr. -

53 Skydj Karaoke List

53 SKYDJ KARAOKE LIST - BHANGRA + BOLLYWOOD FULL LIST 1 ARTIST/MOVIE TITLE ORDER Kuch Na Kaho (Inc Video) 1942 A Love Story (1994) - Singa 92039 Ruth Na Jaana 1942 Love Story - Karaoke 91457 Ruth Na Jaana 1942 Love Story - Singalong 91458 Aal Izz Well 3 Idiots 90047 Behti Hawa Sa Tha Woh 3 Idiots 90048 Give Me Some Sunshine 3 Idiots 90049 Jaana Nahi Denga Tujhe 3 Idiots 90050 Zoobi Doobi 3 Idiots 90051 All Izz Well 3 Idiots - Karaoke 92129 Jawani O Diwan Aaan Milo Sajna - Karaoke 90559 Jawani O Diwan Aaan Milo Sajna - Singalong 90560 Babuji Dheere Chalana Aaar Paar (1954) - Karaoke 92131 Aaj Purani Rahon Se Aadami - Karaoke 90257 Aaj Purani Rahon Se Aadami - Singalong 90258 Sinzagi Ke Rang Aadmi Aur Insaan - Karaoke 90858 Sinzagi Ke Rang Aadmi Aur Insaan - Singalong 90859 Aaj Mere Yaar Ki Shadi Hai Aadmi Sadak Ka - Karaoke 90259 Aaj Mere Yaar Ki Shadi Hai Aadmi Sadak Ka - Singalong 90260 Tota Meri Tota Aaj Ka Gunda Raaj - Karaoke 91157 Tota Meri Tota Aaj Ka Gunda Raaj - Singalong 91158 Ek Pappi De De Aaj Ka Gundarraj - Karaoke 90261 Ek Pappi De De Aaj Ka Gundarraj - Singalong 90262 Aaja Nachle Aaja Nachle 90053 Aaja Nachle - Inc English Trans Aaja Nachle 90052 Aaja Nachle Aaja Nachle - Karaoke 91459 Is Pal Aaja Nachle - Karaoke 91461 Ishq Hua Aaja Nachle - Karaoke 91463 Show me your Jalwa Aaja Nachle - Karaoke 91465 Aaja Nachle Aaja Nachle - Singalong 91460 Is Pal Aaja Nachle - Singalong 91462 Ishq Hua Aaja Nachle - Singalong 91464 Show me your Jalwa Aaja Nachle - Singalong 91466 Tujhe Kya Sunaun Aakhir Deo - Karaoke 91159 Tujhe Kya Sunaun -

Song Title Artists & Movie Title Track

49 SKYDJ KARAOKE LIST - BHANGRA + BOLLYWOOD FULL LIST 1 ARTISTE / SONG TITLE ORDER SONG TITLE ARTISTS & MOVIE TITLE TRACK 2 Step Bhangra The Bilz ft So-D & Kashif 80045 Aa Bhi Ja Sur - Karaoke 90527 Aa Bhi Ja Sur - Singalong 90528 Aa Bhi Ja Sanam Prince (It's Show Tiime) 90191 Aa Chal Ke Tujhe Gagan Ki Chav Me - Karaoke 90367 Aa Chal Ke Tujhe Gagan Ki Chav Me - Singalong 90368 Aa chal ke tujhe - Karaoke Door Gagan Ki Chhaon Mein - Kara 92171 Aa Gaya Aa Gaya Hum Tumare Hai Sanam - Karaoke 91593 Aa Gaya Aa Gaya Hum Tumare Hai Sanam - Singalong 91594 Aa Jao Meri Tamanna Ajab Prem Ki Gazab Kahani 90063 Aa Laut Ke Aaja Mere Meet Rani Roopmati (1959) 91920 Aa Piya in Naino Me Deewar - Karaoke 90335 Aa Piya in Naino Me Deewar - Singalong 90336 Aa Zara Murder 2 (2011) - Singalong 80201 Aada Hai Chandrama NavRang - Karaoke 90447 Aada Hai Chandrama NavRang - Singalong 90448 Aadat JAL (Pakistani Group) - Singalon 92012 Aag Lage Fashion Nu Haal E Dil 90114 Aage Bhi Jane Na Tu Waqt - Karaoke 90545 Aage Bhi Jane Na Tu Waqt - Singalong 90546 Aahun Aahun Love Aaj Kal - Karaoke 91874 Aahun Aahun Love Aaj Kal - Singalong 91875 Aaina Dekha Khap (2011) - Singalong 80197 Aaj Din Chadheya Love Aaj Kal - Karaoke 91876 Aaj Din Chadheya Love Aaj Kal - Singalong 91877 Aaj Kal Lagta Nahi Shoharat - Karaoke 90519 Aaj Kal Lagta Nahi Shoharat - Singalong 90520 Aaj Mausam bada Beyimaan Loafer (1973) - Karaoke 92213 Aaj Mere Yaar Ki Shadi Hai Aadmi Sadak Ka - Karaoke 90259 Aaj Mere Yaar Ki Shadi Hai Aadmi Sadak Ka - Singalong 90260 Aaj Phir Jeene Ki Tammana Guide - Karaoke -

Iifa Awards 2011 Popular Awards Nominations

IIFA AWARDS 2011 POPULAR AWARDS NOMINATIONS BEST FILM MUSIC DIRECTION ❑ Band Baaja Baaraat ❑ Salim - Sulaiman — Band Baaja Baaraat ❑ Dabangg ❑ Sajid - Wajid & Lalit Pandit — Dabangg ❑ My Name Is Khan ❑ Vishal - Shekhar — I Hate Luv Storys ❑ Once Upon A Time In Mumbaai ❑ Vishal Bhardwaj — Ishqiya ❑ Raajneeti ❑ Shankar Ehsaan Loy — My Name Is Khan ❑ Pritam — Once Upon A Time In Mumbaai BEST DIRECTION ❑ Maneesh Sharma — Band Baaja Baaraat BEST STORY ❑ Abhinav Kashyap — Dabangg ❑ Maneesh Sharma — Band Baajaa Baaraat ❑ Sanjay Leela Bhansali — Guzaarish ❑ Abhishek Chaubey — Ishqiya ❑ Karan Johar — My Name Is Khan ❑ Shibani Bhatija — My Name Is Khan ❑ Milan Luthria — Once Upon A Time In Mumbaai ❑ Rajat Aroraa — Once Upon A Time In Mumbaai ❑ Vikramaditya Motwane — Udaan ❑ Anurag Kashyap, Vikramaditya Motwane — Udaan PERFORMANCE IN A LEADING ROLE: MALE LYRICS ❑ Salman Khan — Dabangg ❑ Amitabh Bhattacharya — Ainvayi Ainvayi, Band Baajaa Baraat ❑ Hrithik Roshan — Guzaarish ❑ Faaiz Anwar — Tere Mast Mast, Dabangg ❑ Shah Rukh Khan — My Name Is Khan ❑ Gulzar — Dil Toh Bachcha, Ishqiya ❑ Ajay Devgn — Once Upon A Time In Mumbaai ❑ Niranjan Iyengar — Sajdaa, My Name Is Khan ❑ Ranbir Kapoor — Raajneeti ❑ Irshad Kamil — Pee Loon, Once Upon A Time In Mumbaai PERFORMANCE IN A LEADING ROLE: FEMALE PLAYBACK SINGER: MALE ❑ Anushka Sharma — Band Baaja Baaraat ❑ Vishal Dadlani — Adhoore, Break Ke Baad ❑ Kareena Kapoor — Golmaal 3 ❑ Rahat Fateh Ali Khan — Tere Mast Mast Do Nain, Dabangg ❑ Aishwarya Rai Bachchan — Guzaarish ❑ Shafqat Amanat Ali — Bin Tere, I Hate -

SONG CODE and Send to 4000 to Set a Song As Your Welcome Tune

Type WT<space>SONG CODE and send to 4000 to set a song as your Welcome Tune Song Name Song Code Artist/Movie/Album Aaj Apchaa Raate 5631 Anindya N Upal Ami Pathbhola Ek Pathik Esechhi 5633 Hemanta Mukherjee N Asha Bhosle Andhakarer Pare 5634 Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Ashaa Jaoa 5635 Boney Chakravarty Auld Lang Syne And Purano Sei Diner Katha 5636 Shano Banerji N Subhajit Mukherjee Badrakto 5637 Rupam Islam Bak Bak Bakam Bakam 5638 Priya Bhattacharya N Chorus Bhalobese Diganta Diyechho 5639 Hemanta Mukherjee N Asha Bhosle Bhootader Bechitranusthan 56310 Dola Ganguli Parama Banerjee Shano Banerji N Aneek Dutta Bhooter Bhobishyot 56312 Rupankar Bagchi Bhooter Bhobishyot karaoke Track 56311 Instrumental Brishti 56313 Anjan Dutt N Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Bum Bum Chika Bum 56315 Shamik Sinha n sumit Samaddar Bum Bum Chika Bum karaoke Track 56314 Instrumental Chalo Jai 56316 Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Chena Chena 56317 Zubeen Garg N Anindita Chena Shona Prithibita 56318 Nachiketa Chakraborty Deep Jwele Oi Tara 56319 Asha Bhosle Dekhlam Dekhar Par 56320 Javed Ali N Anwesha Dutta Gupta Ei To Aami Club Kolkata Mix 56321 Rupam Islam Ei To Aami One 56322 Rupam Islam Ei To Aami Three 56323 Rupam Islam Ei To Aami Two 56324 Rupam Islam Ek Jhatkay Baba Ma Raji 56325 Shaan n mahalakshmi Iyer Ekali Biral Niral Shayane 56326 Asha Bhosle Ekla Anek Door 56327 Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Gaanola 56328 Kabir Suman Hate Tomar Kaita Rekha 56329 Boney Chakravarty Jagorane Jay Bibhabori 56330 Kabir Suman Anjan Dutt N Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Jatiswar 56361 -

Sheila Ki Jawani Hd 1080P Lyrics to Hellol

Sheila Ki Jawani Hd 1080p Lyrics To Hellol Sheila Ki Jawani Hd 1080p Lyrics To Hellol 1 / 3 2 / 3 Up next. "Sheila Ki Jawani" Full Song | Tees Maar Khan (With Lyrics) Katrina Kaif - Duration: 4:31. T-Series .... Hello fellas, Enjoy the song Jumme Ki Raat from the action movie KICK starring Salman ... Purani Jeans - Songs Mashup - Remixed by Kiran Kamath Hd 1080p, ... "Sheila Ki Jawani" Full Song | Tees Maar Khan (With Lyrics) Katrina Kaif.. hello frnds my name is umair i hope u enjoy this song follow me guys like and ... Sheila Ki Jawani ~~ Tees .... Agar Tum Mil Jao - Zeher (1080p HD Song) Agar, Song Lyrics, ... "Sheila Ki Jawani" Full Song | Tees Maar Khan (With Lyrics) Katrina Kaif. Party SongsMovie .... Sheila Ki Jawani Full Song Tees Maar Khan HD with Lyrics Katrina kaif.. Sheila Ki Jawani hindi songs Tees Maar Khan HD 1080p ... Lyrical: Dil Diyan Gallan Song with Lyrics | Tiger Zinda Hai |Salman Khan, Katrina Kaif|Irshad Kamil.. "Sheila Ki Jawani" Full Song Tees Maar Khan | HD with Lyrics | Katrina ... The actress will be grooving to the song Hello Hello sung by Rekha .... "Sheila Ki Jawani" Full Song | Tees Maar Khan (With Lyrics) Katrina 00:04:31 ... Katrina Kaif Hot Edit 1080p HD || Sheila Ki Jawani || Navel || 00:04:17 ... Hello beautiful people, welcome to my channel - Hope you enjoy my first video! This is just .... Here's presenting the hit song "Sheila Ki Jawani" (With Lyrics) from the hindi movie 'Tees Maar Khan'. This .... Watch “Sheila Ki Jawani“ Full Song ¦ Tees Maar Khan (With Lyrics) Katrina Kaif fULL hd 1080p - Bollywood .. -

Cover Story BOLLYWOOD HEROINES Return Sirensof THE

Cover Story BOLLYWOOD HEROINES Return SirensOF THE Bollywood’s women get better roles and bigger brands. In 2012, they will go from being beautiful Barbies to power performers. By Nishat Bari pregnant Vidya Balan, 34, slowly walks down a bustling Park Street in Kolkata even as director Sujoy Ghosh and his camera crew struggle with milling crowds to capture the dejection of a woman in desperate search of her husband in Kahaani. The Acrowds wait for the shot to be taken but such is the rush to get closer to the screen Silk Smitha that Ghosh and his team have already been beaten up once. The Dirty Picture grossed Rs 114 crore worldwide in 2011 but Balan had already es- tablished herself as the hero: No One Killed Jessica with Rani Mukherjee made Rs 36 crore in January 2011. Bollywood women have not looked back since Madhur Bhandarkar’s Fashion in 2008. The film saw Priyanka Chopra, 29, sleeping her way to the top in the film, Kangna Ranaut,24, dying of a drug overdose, and Mugdha Godse, 25, the cleanest living model of the group, marrying a gay D KAREENAKAPOOR She was a quirky hairstylist from Los Angeles, Jun Riana Braganza in Ek Main Aur Ekk Tu opposite Imran Khan, is a Pakistani agent in Agent Vinod 1 KAREENA with Saif, and teams up with Aamir Khan and KAPOOR IN THE FORTHCOMING Rani Mukherjee for thriller psychological Talaash. HEROINE Then it’s time to play superstar on the skids Mahi Gill in Madhur Bhandarkar’s Heroine. Mar USP Beautiful, professional, can act. -

Farkhunda Laid to Rest; Ghani Appoints Fact-Finding Team As Lynching Stirs Heat

Eye on the News [email protected] Truthful, Factual and Unbiased Vol:IX Issue No:227 Price: Afs.15 MONDAY . MARCH 23 . 2015 -Hamal 03, 1393 HS www.afghanistantimes.af www.facebook.com/ afghanistantimeswww.twitter.com/ afghanistantimes TROOPS NUMBER A US DOMESTIC ISSUE: GHANI President Ashraf Ghani declared to get into," Ghani emphasized. Syria's national army is one exam- that the numbers of American "We will explain the condition ple," Ghani said. "Here, it is not troops staying in Afghanistan was what we are doing, how we are the physical presence of people a complicated domestic issue of the bringing those efficiencies, and then from Syria or Iraq. It is the net- United States, insisting the Afghan we need to let the internal process work effect." government would not interfere take over, and arrive its decisions Ghani and Abdullah left Kab- into it. that serves our need, the regions, ul for the United States on Satur- ic transition will be chaired by Lew. his CEO. Ghani expressed these state- the global needs and the security day night where they would meet After that, there will be a press A gathering of Afghan-Ameri- ments on Saturday in a briefing to of United States." the U.S. President Barack Obama, conference at Camp David, a re- can Diaspora, civil society lead- the reporters, just hours before In addition, Ghani for the first Vice President Joe Biden, Congress turn to Washington and then the ers, media representatives, NGOs leaving to the United States along time publicly expressed his con- members, the NATO Secretary Afghans have an event for Mon- and a range of key stakeholders General Jens Stoltenberg, Secre- day s evening on economic issues. -

Here, Effect SIMCA Challenges the Copyright Board Right Constitution

INTERVIEW F George Brooks SOUND Sajid-Wajid REGULARS F Offbeat: Strum the Junk! Venue Watch: BOXFebruary 2011 I Volume 1 I Issue 7 I ` 150 Bflat, Bengaluru Watch Tower: Bengaluru ww Right E Clause and Here, Effect SIMCA challenges the Copyright Board Right constitution Now E Sing Along! Are we about to witness the boom of karaoke in the country? E E E Rajya Sabha MP, script writer, lyricist and now, crusader for the creative fraternity. Saptak, Javed Akhtar on why he is convinced the Baajaa Gaajaa Indian Copyright Act should be amended 2011 kicks off with interesting music fests across the country I Publisher’s Note SOUND Final Act? BOX n a few days’ time, on February 21, both Houses of the Indian parliament February 2011 I Volume 1 I Issue 7 Iwill reconvene for the Budget session. MASTHEAD It remains to be seen whether parliamentary business will be struck by the same state of paralysis that characterized the Winter session a few months back. However, indications are that the government has been goaded into a PUBLISHER Nitin Tej Ahuja more flexible and accommodative stance on the opposition’s main demand of [email protected] a JPC investigation into the telecom spectrum auction controversy. Therefore, EDITOR it is possible that we may have a normal parliamentary session. Of course, Aparna Joshi the word ‘normal’ is used here rather generously given our parliamentarians’ [email protected] propensity for drama and shenanigans. CREATIVE DIRECTOR Sajid Moinuddin www.hbdesign.in From the music industry’s perspective, the million dollar question undoubtedly is whether this session will see the coming into law of the very CORRESPONDENTS Anita Iyer contentious amendments to the Copyright Act. -

Contemporary Bollywood Dance: Analyzing It Through the Interplay of Social Forces

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 6, Issue 6, June 2016 54 ISSN 2250-3153 Contemporary Bollywood Dance: Analyzing It through the Interplay of Social Forces Esha Bhattacharya Chatterjee Department of Sociology, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India Ph.D Scholar Abstract- Bollywood, or the Hindi Film industry, embraces a However, the issue of whether the term ‘Bollywood’ is a truly enigmatic world of its own. The craze and euphoria pejorative or subversive description of Bombay (present surrounding it, not only in India but also in foreign lands, is Mumbai) remains unresolved. something worth witnessing. One of the major attractions of Interestingly Bollywood is not simply about movies. In Bollywood, which in fact distinguishes it from Hollywood, is its fact, movies on celluloid set the tone for events in popular Indian elaborate song-dance sequences which never fail to strike a chord culture and shape the taste and ideals of beauty. Thus, in a way with the audience. Its creation of sublime, emotional or foot- Hindi cinema is deeply intertwined within our social fabric. tapping escapism is simply unmatched anywhere in the world. A Indians adore their actors as icons so much so that their actions fact often overlooked is that, these songs and dances are have a huge impact on the daily lives of Indian citizens. intricately woven in our social fabric. It is interesting to take note Therefore, it is highly significant as an Indian cultural of this and undertake an analysis of the same. In this article, I phenomenon too. However, the features of Bollywood are not shall discuss about Bollywood, how the dances and songs are always comprehensible for everyone, especially for those who placed within movies, analyse the dance types, its forms in the are not quite familiar with the cultures and traditions of Indian context of social forces operating within it- ‘globalization’ and society. -

Item Songs in Hindi Cinema and the Postfeminist Debate

Pakistan Journal of Women’s Studies: Alam-e-Niswan Vol. 24, No.2, 2017, pp.1-14, ISSN: 1024-1256 ITEM SONGS IN HINDI CINEMA AND THE POSTFEMINIST DEBATE Shirin Zubair Department of English, Kinnaird College for Women, Lahore Abstract Item songs in mainstream (read=malestream) Indian cinema are difficult to decode as cultural narratives due to their polysemous linguistic and visual messages, particularly in the wake of the backlash feminism has earned in an era of (post) feminism. Rather than follow the conventional feminist approach to decode such songs as sexualizing and objectifying women, this essay reads an alternative narrative into some of these songs, by arguing that blurring the boundaries between the erstwhile ‘bad woman’ or ‘vamp’ and the modern Indian woman who is sexually liberated, independent and in control, such songs articulate a postfeminist discourse with regard to Indian femininities. To this end, I analyze two very popular item songs in recent years Shiela ki jawani (Tees Maar Khan, 2010) and chikni chameli (Agneepath, 2012), while applying the (post) feminist critique (McRobbie, 2009; Fraser, 2016) to argue that these songs position women as sexually active, independent and agentive. They also resonate with the wider socio-cultural practices in urban India: the changing lifestyles, practiced and lived femininities of the young urban women, as well as the new breed of leading Indian female actors, who display no inhibitions in performing these songs. Seen in this perspective, the songs provide a site or space for diverse and oppositional practices regarding feminism and traditional femininities; while songs like chikni chameli, Shiela ki jawani celebrate the new woman’s empowerment through sexual liberation, her autonomy, individuation and freedom, yet simultaneously position women—through rampant sexism in lyrics and itemization of body parts through a camera lens---as the classic object of the male gaze (Mulvey, 1999).