A Grammar Will Alexander On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LANGUAGE POETRY Entry for the Greenwood Encyclopedia of American Poetry (2005)

Craig Dworkin: LANGUAGE POETRY Entry for The Greenwood Encyclopedia of American Poetry (2005) The discrepancy between the number of people who hold an opinion about Language Poetry and those who have actually read Language Poetry is perhaps greater than for any other literary phenomenon of the later twentieth century. For just one concrete indicator of this gap, a primer on "The Poetry Pantheon" in The New York Times Magazine (19 February, 1995) listed Paul Hoover, Ann Lauterbach, and Leslie Scalapino as the most representative “Language Poets” — a curious choice given that neither Hoover nor Lauterbach appears in any of the defining publications of Language Poetry, and that Scalapino, though certainly associated with Language Poetry, was hardly a central figure. Indeed, only a quarter-century after the phrase was first used, it has often come to serve as an umbrella term for any kind of self-consciously "postmodern" poetry or to mean no more than some vaguely imagined stylistic characteristics — parataxis, dryly apodictic abstractions, elliptical modes of disjunction — even when they appear in works that would actually seem to be fundamentally opposed to the radical poetics that had originally given such notoriety to the name “Language Poetry” in the first place. The term "language poetry" may have first been used by Bruce Andrews, in correspondence from the early 1970s, to distinguish poets such as Vito Hannibal Acconci, Carl Andre, Clark Coolidge, and Jackson Mac Low, whose writing challenged the vatic aspirations of “deep image” poetry. In the tradition of Gertrude Stein and Louis Zukofksy, such poetry found precedents in only the most anomalous contemporary writing, such as John Ashbery's The Tennis Court Oath, Aram Saroyan's Cofee Coffe, Joseph Ceravolo's Fits of Dawn, or Jack Kerouac's Old Angel Midnight. -

Poetry and Performance: Listening to a Multi-Vocal Canada

0Poetry and Performance: Listening to a Multi-Vocal Canada by Katherine Marikaan McLeod A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English, University of Toronto © Copyright by Katherine Marikaan McLeod (2010) ii Poetry and Performance: Listening to a Multi-Vocal Canada Doctor of Philosophy (2010) Katherine Marikaan McLeod Graduate Department of English, University of Toronto 1Abstract Performances of poetry constitute significant cultural and literary events that challenge the representational limits and possibilities of transposing written words into live and recorded media. However, there has not been a comprehensive study of Canadian poetry that focuses specifically on performance. This dissertation undertakes a theorizing of performance that foregrounds mediation, audience, and presence (both readerly and writerly). The complex methodology combines theoretical approaches to reading (Linda Hutcheon on adaptation, Wolfgang Iser on the reader, and Roland Barthes on the materiality of writing) with poetics as theorized by Canadian poets (namely bpNichol, Steve McCaffery, Jan Zwicky, Robert Bringhurst) in order to argue that performances of poetry are responsive exchanges between performers and audiences. Importantly, the dissertation argues that performances of poetry call for a re-evaluation of reading as listening, thereby altering the interaction between audience and performance from passive to participatory. Arranged in four chapters, the dissertation examines a range of Canadian poets and performances: The Four Horsemen (Rafael Barreto-Rivera, Paul Dutton, Steve McCaffery, and bpNichol), dance adaptations of Michael Ondaatje’s poems, George Elliott Clarke’s poetic libretti, and Robert Bringhurst’s polyphonic poetry. Following the Introduction’s iii outlining of the term performance, Chapter One examines processes of recording and adapting avant-garde sound poetry, specifically in the sound and written poetry of Nichol and McCaffery. -

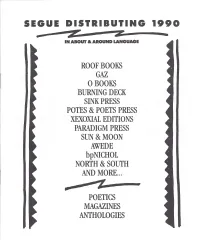

Z: • in ABOUT & AROUND LANGUAGE

F--~~-~- SEGUE DISTRIBUTING 1990 $5 Z z: • IN ABOUT & AROUND LANGUAGE ROOF BOOKS GAZ oBOOKS BURNING DECK SINK PRESS POTES & POETS PRESS XEXOXIAL EDITIONS PARADIGM PRESS SUN &MOON AWEDE bpNICHOL NORTH & SOUTH AND MORE... .......~4__.. $I I- POETICS MAGAZINES ANTHOLOGIES p--------- FEATURED PRESSES ROOF BOOKS Raik by Ray DiPalma The one hundred poems in Ray DiPalma's new collection con The Politics ofPoetic Form: Poetry andPublic Policy tinue his experiments with the poetic line that began in the early Edited by Charles Bernstein 1970s with works such as The Sargasso Transcries, Soli, and Marquee, as well as the long lyric poem Planh. Raik articulates Acollection of 14 essays by contemporary poets and critics that the dynamic variety possible within the fixed form set for each expand on the discussions presented in L=A= N= G= U= poem in the book. A= G= E, focussing on the political and ideological dimensions of the formal and stylistic practices of contemporary poetry. There is a wide range of subject matter to be found here: the lyri These essays were originally presented at the Wolfson Center for cal qualities of Elizabethan underworld slang and the contem National Affairs of the New School for Social Research in New porary urban landscape; meditations on moments in history from York. Each essay is accompanied by an edited transcript of the ancient Egypt and Roman Britain to the Italian Renaissance. discussion that took place at the New School following the initial These choices of subject spotlight DiPalma's assiduous attention presentation. to details. The word choices in each poem stir awareness of each The Politics ofPoetic Form includes full-length essays by Jerome letter in the line. -

Ron Silliman Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf696nb4f8 No online items Ron Silliman Papers Finding aid prepared by Special Collections & Archives Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla, California, 92093-0175 858-534-2533 [email protected] Copyright 2005 Ron Silliman Papers MSS 0075 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Ron Silliman Papers Identifier/Call Number: MSS 0075 Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla, California, 92093-0175 Languages: English Physical Description: 10.4 Linear feet(26 archives boxes) Date (inclusive): 1965-1988 Abstract: Papers of Ron Silliman, American writer and editor. Silliman has lived in the San Francisco Bay Area most of his life and is associated with the Language school of contemporary writers. He edited the anthology In The American Tree, published in 1986. The papers include extensive correspondence with many prominent contemporary writers, including Rae Armantrout, Charles Bernstein, Michael Davidson, Lyn Hejinian, Douglas Messerli, John Taggart, and Hanna Weiner. Also included are drafts of Silliman's published works, notebooks, and materials relating to In the American Tree. The collection is divided into five series: 1) ORIGINAL FINDING AID, 2) CORRESPONDENCE, 3) WRITINGS, 4) IN THE AMERICAN TREE and 5) ORIGINALS OF PRESERVATION PHOTOCOPIES. Creator: Silliman, Ronald, 1946- Scope and Content of Collection The Ron Silliman papers contain collected correspondence and writings related to Silliman's career as a writer. The materials cover a range from the mid-1960s to 1988, excluding his most recent publication WHAT (1988). The collection is divided into five series: 1) ORIGINAL FINDING AID, 2) CORRESPONDENCE, 3) WRITINGS, 4) IN THE AMERICAN TREE and 5) ORIGINALS OF PRESERVATION PHOTOCOPIES. -

Reading In-Between Language, Image, and Things in the Writing of Lyn Hejinian

Reading In-between Language, Image, and Things in the Writing of Lyn Hejinian Marina M. Mihova A thesis submitted in fufilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy UNSW School of the Atis and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences December 2012 THE UNIVERSITY Of NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Mihova l=irst name: Marina Other name/s: Mihova Abbreviation fOI' degree as given in the University calendar PhD School: School of Arts and Media Faculty: Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Title: The dream of "La Faustienne"- Reading in-between language, image, and things in the writing of Lyn Hejinian Abstract This dissertation examines a terrain of liminality evident in the works of American poet, Lyn Hejilnian. whose writing utilizes imagery (ranging from the verbally visual to the explicitly graphic) and a form of Steinian materiality, in the development of a poetic which moves away from the domain of textual representation towards a new form of realism which challenges existing notions of ideology and perception. Drawing upon W.J.T. Mitchell's t.heories of visuality and Gaston Bachelard's theorization of the on,eiric qualities of writing. as well as on Freudian dream theory, this thesis maps out how the cross disciplinary dimensions ofHt!jinian's poetry, render into being a speaking female subject. Chapter one provides a contextual framework for Hej inian's writing, articulating the integral role notions of community and collaboration play in the development of a form of writing situated within a space of in-between. -

The Index of the Quotidian: Folk Music and Language Poetry

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Jim & Mary Lois Hulsman Undergraduate 2020 Award Winners Library Research Award Fall 2019 The Index of the Quotidian: Folk Music and Language Poetry Gus Tafoya University of New Mexico - Main Campus, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ugresearchaward_2020 Part of the American Literature Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Tafoya, Gus. "The Index of the Quotidian: Folk Music and Language Poetry." (2019). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ugresearchaward_2020/2 This Emerging Researcher is brought to you for free and open access by the Jim & Mary Lois Hulsman Undergraduate Library Research Award at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2020 Award Winners by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. 1 The Index of the Quotidian: Folk Music and Language Poetry Gus Tafoya Poetry in a Digital Age November 23rd, 2019 Folk music has earned the reputation of being one of the most authentic and fundamental artistic expressions of the recent modern generation. In part because of the adverseness of it’s artists to entering the commercial sphere in favor of remaining more closely linked to the experiences of their respective communities, re-considering the relationship to music and those who it engages. This nuanced decision is not unlike the mission and process of the 1970’s Language Poets, who’s radical view of “life as language” caused their own collaborative process to similarly express a utilitarian view of community consciousness and the quotidian. -

The Language Poetry Mission

LINKING WORDS WITH THE WORLD: THE LANGUAGE POETRY MISSION Saroj Koirala ABSTRACT The poets associated with the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E School have remarkably borrowed from the Pound-Olson tradition of political poetry and poetics. But, they have also experimented with newer methods and matters that deviate from the tradition. Such continuation and departure from the tradition of the socio-cultural oriented language poets has been investigated here. Their poetic tenets have been examined through the ideas formulated by the outstanding cultural critics; Adorno, Jameson, Bakhtin, Foucault, Lukács, and Benjamin. Based on the thorough examination it has been found out that besides many other socio-cultural demands the language poets want to connect the words of art the world people live. Such connection, as they perform, has been disturbed for long time. Key Words: Prose-poetry, space and form, ideological literature, textual politics, disruptions, praxis. Among numerous schools, tendencies, and groups of contemporary American poetry a sharp division between traditional and experimental is noteworthy. The cooked and the raw poetry, closed and open form, new formalist and language poetry are further chains of this division (Caplan, 123). Language poetry—a significant wing of the second type—is innovative, creative and challenging. It is a school of radicalism in American poetics. Not only linguistically innovative this school of avant-garde school writers is fully committed to emerging alternative values of taste. These poets do maintain a unique affinity and departure with the established tradition of Pound-Olson poetics. Language poetry refers to all the different writing practices demonstrated by a rather loose group of writing communities, mostly printed in magazines such as This, Tottel’s, L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E and Poetics Journal. -

The Perverse Library

the perverse library The Perverse Library CRAIG DWORKIN the perverse library Craig Dworkin Published 2010 by information as material York, England information as material publishes work by artists and writers who use extant material — selecting it and re-framing it to generate new meanings — and who, in doing so, disrupt the existing order of things. www.informationasmaterial.com ISBN 978-1-907468-03-2 Cover image Étienne-Louis Boullée Deuxieme projet pour la Bibliothèque du Roi, 1785 Typography Groundwork, Skipton, England Printed in Great Britain by Henry Ling, The Dorset Press, Dorchester Contents Pinacographic Space . 9 The Perverse Library . 45 A Perverse Library . 53 Pinacographic Space The library is its own discourse. You listen in, don’t you? — Thomas Nakell, The Library of Thomas Rivka 9 ne night, a friend — a poet who had been one of the Ocentral fi gures in Language Poetry — noticed me admir- ing his collection of books, which lined his entire apartment, fl oor to ceiling. Political theory crowded the entryway; music and design pushed up against the dining room; in the living room he seemed to have a complete collection of publications from his fellow travelers: the most thorough document of post-war American avant-garde poetry imaginable. I noticed, one after another, books of which I had only heard mention but had never before seen. At the top of one shelf I thought I caught a glimpse of Robert Grenier’s infamous “chinese box”- bound set of cards, Sentences. I tried to express my admiration by saying something about the especially choice inclusions, mentioning a couple of particularly obscure volumes to let him know that it wasn’t just an off-hand compliment, or a statement about the sheer number of books, and that I had really read the shelves carefully and knew just how impres- sively replete the collection was. -

Breaking the Letter: Illegibility As Intersign in Cy Twombly, Steve Mccaffery, and Susan Howe

BREAKING THE LETTER: ILLEGIBILITY AS INTERSIGN IN CY TWOMBLY, STEVE MCCAFFERY, AND SUSAN HOWE by Michael Rinaldo A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Professor Yopie Prins, Chair Professor Matthew N. Biro Professor Michèle A. Hannoosh Professor Alexander D. Potts ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Anyone who has worked on a dissertation or a book knows firsthand the difficulty (and the occasional absurdity) involved. For this, I cannot sufficiently thank those who kept me from being discouraged: Yopie Prins, my dissertation chair and closest reader over the years, for her infinite patience and generous guidance; Michèle Hannoosh, for her help in navigating the vast world of 19th-century France and her critical feedback on the theoretical problems surrounding text and image; Alex Potts, for his constructive feedback as an art historian and the course that inspired the idea for the first chapter; Matt Biro, for yet another art historical perspective on the project and prodding questioning of my methodology; and Silke Weineck, for her encouragement throughout the years up until the first half of the dissertation writing. The following parties also provided crucial support: Rackham Graduate School, for the Rackham Predoctoral Fellowship (2011-2012) along with several research and conference travel grants; the Comparative Literature office staff—Paula Frank, Nancy Harris, and Judy Gray—for help with departmental paperwork and classroom preparation; and the librarians at the Archive for New Poetry at UC-San Diego, for their assistance in perusing the letters of Susan Howe. -

Charles Bernstein Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt896nd20f No online items Charles Bernstein Papers Mandeville Special Collections Library Mandeville Special Collections Library The UCSD Libraries 9500 Gilman Drive University of California, San Diego La Jolla, California 92093-0175 Phone: (858) 534-2533 Fax: (858) 534-5950 URL: http://orpheus.ucsd.edu/speccoll/ Copyright 2005 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Charles Bernstein Papers MSS 0519 1 Descriptive Summary Creator: Bernstein, Charles, 1950- Title: Charles Bernstein Papers, Date (inclusive): 1962-2000 Extent: 50.00 linear feet(129 archives boxes, 5 card file boxes and 5 oversize folders) Abstract: Papers of Charles Bernstein, writer, editor, librettist, educator, and publisher, who is most often associated with L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, a body of writing named for the journal (1978-1982) by this name which Bernstein co-edited with Bruce Andrews. Bernstein writes poetry, essays and librettos which foreground the materiality and sociality of language as it exists in different contexts. The papers include correspondence with writers, artists, publishers and friends; manuscript drafts and production materials for his collected works, especially CONTENT'S DREAM (1986), A POETICS (1992) and MY WAY (1998); notebooks and journals (1971-1994); and uncollected poem drafts and working papers. Also included are drafts for the multi-authored poem LEGEND written with Ray DiPalma, Bruce Andrews, Steve McCaffery, and Ron Silliman. Bernstein's editorial work on Asylum's Press publications, the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E Journal, the Segue Catalog, BOUNDRY 2: 43 POETS and BOUNDRY 2: 99 POETS, as well as numerous smaller projects are well represented. -

The Steve Mccaffery Archive

The Steve McCaffery Archive The Archive offers a distinct opportunity for rich scholarly exploration into concrete, sound, and language poetry through published and unpublished manuscripts, correspondence, drawings, journals, sketchbooks, audio/video recordings and ephemera. Photo illustration (not part of the archive) based on the poster “Four Horsemen Canadada,” shown below. “Though he would be among the first people to point out the inherent problems with the terminology, poet and scholar Steve McCaffery is one of the major architects of postmodern Canadian literature and was a major player in the Canadian avant-garde of the 1970s. With fellow poet bpNichol, he formed the Toronto Research Group in 1973 … With Nichol, Paul Dutton and Rafael Barreto-Rivera, McCaffery also formed the highly influential sound poetry collective, The Four Horsemen. McCaffery’s writing, both creative and critical, is concerned to some extent with going beyond the sentence and the word, beyond syntax.” — Ryan Cox, “Trans-Avant-Garde: An Interview with Steve McCaffery,” Taxi Online Edition, Winter 2007/2008 . Steve McCaffery (1947–) Poet and scholar Steve McCaffery was born in Sheffield, England. He received his B.A. from Hull University, his M.A. from York University, and his Ph.D. from the program in poetics, English, and comparative literature at SUNY Buffalo. He is a scholar, poet, and performer whose wide-ranging influence is especially present in concrete and sound poetry. His numerous books of poetry include the full-length collections Modern Reading: Poems 1969–1990 (Writers Forum, 1991), Seven Pages Missing: Selected Texts Volume One (Coach House Press, 2001) and Volume Two (Coach House Press, 2002), Verse and Worse: Selected and New Poems of Steve McCaffery 1989– 2009 (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2010). -

Michael Lally Archive the Archive Contains Extensive Material Documenting the Life and Work of Poet, Small Press Publisher, and Actor Michael Lally

Michael Lally Archive The archive contains extensive material documenting the life and work of poet, small press publisher, and actor Michael Lally. It is particularly strong in correspondence related to Lally's involvement with the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets during their formative years and the poetry communities in Iowa City, Washington, D.C., and New York City. The diversity of the material in the archive is a reflection of the wide arc of Michael Lally's life and is also the archive's strength. Michael Lally on the cover of Little Caesar, Michael Lally on the cover of Home Planet News, no. 11, 1980. The issue also includes poetry vol. 2, no. 1, Summer, 1980. by Michael and an interview with him conducted by Tim Dlugos. As a poet, a fearless, edgy poet, Michael Lally has been giving readers his version of history for the past 35 years. He has done so with the political forthrightness and performance punch of Ginsberg, with the wit and language skills of O'Hara. But because of the place of poetry in this country, a bard like Lally, while a member of the Pantheon to all manner of poets, remains unknown to the public at large... — Bob Holman The François Villon of the 70s. — John Ashbery Michael Lally is a fine poet and looks straight into your eyes. — James Schuyler in "The Morning of the Poem" The Cosmic Jitterbug! He's all appetite. — Ray DiPalma A damn good poet, man. — Etheridge Knight . Brief Biography of Michael Lally Michael Lally was born into an Irish American South Orange, New Jersey working class family.