Gilbert Varga, Conductor Daniel Müller-Schott, Cello

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edouard Lalo Symphonie Espagnole for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 21

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Edouard Lalo Born January 27, 1823, Lille, France. Died April 22, 1892, Paris, France. Symphonie espagnole for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 21 Lalo composed the Symphonie espagnole in 1874 for the violinist Pablo de Sarasate, who introduced the work in Paris on February 7, 1875. The score calls for solo violin and an orchestra consisting of two flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, triangle, snare drum, harp, and strings. Performance time is approximately thirty-one minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lalo's Symphonie espagnole were given at the Auditorium Theatre on April 20 and 21, 1900, with Leopold Kramer as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. Bizet's Carmen is often thought to have ignited the French fascination with all things Spanish, but Edouard Lalo got there first. His Symphonie espagnole—a Spanish symphony that's really more of a concerto—was premiered in Paris by the virtuoso Spanish violinist Pablo de Sarasate the month before Carmen opened at the Opéra-Comique. And although Carmen wasn't an immediate success (Bizet, who died shortly after the premiere, didn't live to see it achieve great popularity), the Symphonie espagnole quickly became an international hit. It's still Lalo's best-known piece by a wide margin, just as Carmeneventually became Bizet's signature work. Although the surname Lalo is of Spanish origin, Lalo came by his French first name (not to mention his middle names, Victoire Antoine) naturally. His family had been settled in Flanders and in northern France since the sixteenth century. -

Season 2014-2015

23 Season 2014-2015 Wednesday, January 28, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, January 30, at 2:00 Saturday, January 31, Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor at 8:00 Kirill Gerstein Piano Beethoven Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 I. Allegro con brio II. Andante con moto III. Allegro— IV. Allegro Intermission Shostakovich Piano Concerto No. 2 in F major, Op. 102 I. Allegro II. Andante III. Allegro Shostakovich/from Suite from The Gadfly, Op. 97a: arr. Atovmyan I. Overture: Moderato con moto III. People’s Holiday: [Allegro vivace] VII. Prelude: Andantino XI. Scene: Moderato This program runs approximately 1 hour, 40 minutes. The January 28 concert is sponsored by MEDCOMP. designates a work that is part of the 40/40 Project, which features pieces not performed on subscription concerts in at least 40 years. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 Please join us immediately following the January 30 concert for a Chamber Postlude, featuring members of The Philadelphia Orchestra. Brahms Piano Quartet No. 3 in C minor, Op. 60 I. Allegro non troppo II. Scherzo: Allegro III. Andante IV. Finale: Allegro lomodo Mark Livshits Piano Kimberly Fisher Violin Kirsten Johnson Viola John Koen Cello 3 Story Title 25 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra is one of the preeminent orchestras in the world, renowned for its distinctive sound, desired for its keen ability to capture the hearts and imaginations of audiences, and admired for a legacy of imagination and innovation on and off the concert stage. -

Piano; Trio for Violin, Horn & Piano) Eric Huebner (Piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (Violin); Adam Unsworth (Horn) New Focus Recordings, Fcr 269, 2020

Désordre (Etudes pour Piano; Trio for violin, horn & piano) Eric Huebner (piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (violin); Adam Unsworth (horn) New focus Recordings, fcr 269, 2020 Kodály & Ligeti: Cello Works Hellen Weiß (Violin); Gabriel Schwabe (Violoncello) Naxos, NX 4202, 2020 Ligeti – Concertos (Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Chamber Concerto for 13 instrumentalists, Melodien) Joonas Ahonen (piano); Christian Poltéra (violoncello); BIT20 Ensemble; Baldur Brönnimann (conductor) BIS-2209 SACD, 2016 LIGETI – Les Siècles Live : Six Bagatelles, Kammerkonzert, Dix pièces pour quintette à vent Les Siècles; François-Xavier Roth (conductor) Musicales Actes Sud, 2016 musica viva vol. 22: Ligeti · Murail · Benjamin (Lontano) Pierre-Laurent Aimard (piano); Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; George Benjamin, (conductor) NEOS, 11422, 2016 Shai Wosner: Haydn · Ligeti, Concertos & Capriccios (Capriccios Nos. 1 and 2) Shai Wosner (piano); Danish National Symphony Orchestra; Nicolas Collon (conductor) Onyx Classics, ONYX4174, 2016 Bartók | Ligeti, Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Concerto for violin and orchestra Hidéki Nagano (piano); Pierre Strauch (violoncello); Jeanne-Marie Conquer (violin); Ensemble intercontemporain; Matthias Pintscher (conductor) Alpha, 217, 2015 Chorwerk (Négy Lakodalmi Tánc; Nonsense Madrigals; Lux æterna) Noël Akchoté (electric guitar) Noël Akchoté Downloads, GLC-2, 2015 Rameau | Ligeti (Musica Ricercata) Cathy Krier (piano) Avi-Music – 8553308, 2014 Zürcher Bläserquintett: -

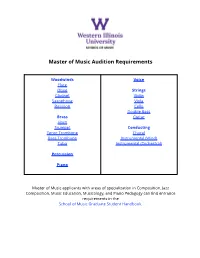

Audition Requirements

Master of Music Audition Requirements Woodwinds Voice Flute Oboe Strings Clarinet Violin Saxophone Viola Bassoon Cello Double Bass Brass Guitar Horn Trumpet Conducting Tenor Trombone Choral Bass Trombone Instrumental (Wind) Tuba Instrumental (Orchestral) Percussion Piano Master of Music applicants with areas of specialization in Composition, Jazz Composition, Music Education, Musicology, and Piano Pedagogy can find entrance requirements in the School of Music Graduate Student Handbook. Flute Faculty: Dr. Suyeon Ko; Email: [email protected] • Mozart: Concerto in G Major or D Major, K. 313 or K. 314 (Movements I and II) • A 19th- or 20th-century French work from Flute Music by French Composers or equivalent • An unaccompanied 20th- or 21st-century work • Five orchestral excerpts from Baxtresser, Orchestral Excerpts for Flute, or equivalent • Sight reading Oboe Faculty: Emily Hart; Email: [email protected] • Choose two from the following: ◦ Saint-Saëns or Poulenc sonata (Movement I) ◦ Mozart or Haydn concerto (Movement III) ◦ Any Telemann or Vivaldi concerto or sonata (Movements I and II) ◦ Britten Six Metamorphoses (any three movements) • Choose two of the following orchestral excerpts (all excerpts may be found in the Rothwell books, Difficult Passages, published by Boosey and Hawkes): ◦ Brahms: Violin Concerto (slow movement excerpt) ◦ Rossini: La Scala di Seta (slow and fast excerpts) ◦ Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 (excerpts from Movements III and IV) ◦ Prokofiev: Symphony No. 1 (excerpts from Movements III and IV) • Sight reading Clarinet Faculty: Eric Ginsberg; Email: [email protected] • Choose two movements from one of the following: ◦ Mozart: Concerto in A Major, K. 622 ◦ Weber: Concerto No. 1 in F Minor, Op. -

An Analysis of Honegger's Cello Concerto

AN ANALYSIS OF HONEGGER’S CELLO CONCERTO (1929): A RETURN TO SIMPLICITY? Denika Lam Kleinmann, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: Eugene Osadchy, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor David Schwarz, Committee Member Daniel Arthurs, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kleinmann, Denika Lam. An Analysis of Honegger’s Cello Concerto (1929): A Return to Simplicity? Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2014, 58 pp., 3 tables, 28 examples, 33 references, 15 titles. Literature available on Honegger’s Cello Concerto suggests this concerto is often considered as a composition that resonates with Les Six traditions. While reflecting currents of Les Six, the Cello Concerto also features departures from Erik Satie’s and Jean Cocteau’s ideal for French composers to return to simplicity. Both characteristics of and departures from Les Six examined in this concerto include metric organization, thematic and rhythmic development, melodic wedge shapes, contrapuntal techniques, simplicity in orchestration, diatonicism, the use of humor, jazz influences, and other unique performance techniques. Copyright 2014 by Denika Lam Kleinmann ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..iv LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES………………………………………………………………..v CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION………..………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER II: HONEGGER’S -

Female Composer Segment Catalogue

FEMALE CLASSICAL COMPOSERS from past to present ʻFreed from the shackles and tatters of the old tradition and prejudice, American and European women in music are now universally hailed as important factors in the concert and teaching fields and as … fast developing assets in the creative spheres of the profession.’ This affirmation was made in 1935 by Frédérique Petrides, the Belgian-born female violinist, conductor, teacher and publisher who was a pioneering advocate for women in music. Some 80 years on, it’s gratifying to note how her words have been rewarded with substance in this catalogue of music by women composers. Petrides was able to look back on the foundations laid by those who were well-connected by family name, such as Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel, and survey the crop of composers active in her own time, including Louise Talma and Amy Beach in America, Rebecca Clarke and Liza Lehmann in England, Nadia Boulanger in France and Lou Koster in Luxembourg. She could hardly have foreseen, however, the creative explosion in the latter half of the 20th century generated by a whole new raft of female composers – a happy development that continues today. We hope you will enjoy exploring this catalogue that has not only historical depth but a truly international voice, as exemplified in the works of the significant number of 21st-century composers: be it the highly colourful and accessible American chamber music of Jennifer Higdon, the Asian hues of Vivian Fung’s imaginative scores, the ancient-and-modern syntheses of Sofia Gubaidulina, or the hallmark symphonic sounds of the Russian-born Alla Pavlova. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Walton - a List of Works & Discography

SIR WILLIAM WALTON - A LIST OF WORKS & DISCOGRAPHY Compiled by Martin Rutherford, Penang 2009 See end for sources and legend. Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Catalogue No F'mat St Rel A BIRTHDAY FANFARE Description For Seven Trumpets and Percussion Completion 1981, Ischia Dedication For Karl-Friedrich Still, a neighbour on Ischia, on his 70th birthday First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Recklinghausen First 10-Oct-81 Westphalia SO Karl Rickenbacher Royal Albert Hall L'don 7-Jun-82 Kneller Hall G E Evans A LITANY - ORIGINAL VERSION Description For Unaccompanied Mixed Voices Completion Easter, 1916 Oxford First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel Hereford Cathedral 3.03 4-Jan-02 Stephen Layton Polyphony 01a HYP CDA 67330 CD S Jun-02 A LITANY - FIRST REVISION Description First revision by the Composer Completion 1917 First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel Hereford Cathedral 3.14 4-Jan-02 Stephen Layton Polyphony 01a HYP CDA 67330 CD S Jun-02 A LITANY - SECOND REVISION Description Second revision by the Composer Completion 1930 First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel St Johns, Cambridge ? Jan-62 George Guest St Johns, Cambridge 01a ARG ZRG -

2013-2014 Subscription Series

2013-2014 Subscription Series Fri. Sun. Thursday 6 8PM 8PM Fri 9 2PM Saturday 6 8PM Sat. 9 8PM 2PM 2013-2014 Subscription Series A B C D A B A B C D A B September Fri. Sun. Beethoven 9 PREMIuM Thursday 6 8PM 8PM Fri 9 2PM Saturday 6 8PM Sat. 9 8PM 2PM Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Beethoven Calm Sea and Sept. Sept. Sept. Sept. Westminster Symphonic Choir Prosperous Voyage A B C D A B A B C D A B Joe Miller Director Muhly “Bright Mass with Canons” 26 27 28 28 Beethoven Symphony September No. 9 (“Choral”) Beethoven 9 PREMIuM Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Beethoven Calm Sea and Sept. Sept. Sept. Sept. OctoberWestminster Symphonic Choir Prosperous Voyage Joe Miller Director Muhly “Bright Mass with Canons” 26 27 28 28 Mahler 4 Beethoven Symphony Oct. Oct. Oct. Oct. Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Britten No. 9 (“Choral”)Variations and Fugue Richard Woodhams Oboe on a Theme of Purcell 4 5 5 6 Christiane Karg Soprano Strauss Oboe Concerto October Mahler Symphony No. 4 Mahler 4 Oct. Oct. Oct. Oct. BronfmanYannick Nézet-Séguin Plays BeethovenConductor Britten Variations and Fugue Richard Woodhams Oboe on a Theme of Purcell Semyon Bychkov Conductor Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 4 Oct. 4 Oct. Oct. 5 5 6 Christiane Karg Soprano Strauss Oboe Concerto Yefim Bronfman Piano Shostakovich Symphony No. 11 Mahler Symphony No. 4 10 11 12 (“The Year 1905”) BronfmanPines of Rome Plays BeethovenPREMIuM Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos Beethoven Overture to Semyon Bychkov Conductor Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 4 Oct. Oct. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2008

and El Corpus en Sevilla) was premiered on May 9, 1906, at the Salle Pleyel in Paris by the pianist Blanche Selva, who later gave the first performance of Volume II {Rondena, Almeria, and Triana) on September 11, 1907, in St. Jean de Luz. Volume III {ElAlbaicin, El polo, Lavapies) was published in 1907 in Paris, Volume IV {Malaga, Jerez, Eritana) also in Paris in 1908, the year before his death. Born in Madrid, violinist-conductor-composer Enrique Fernandez Arbos (1863-1939) was conductor of the Madrid Symphony Orchestra until resigning in 1936 following the outbreak of Civil War. A brilliant orchestrator, his instrumentation of music from Albeniz's flm'flwas particularly popular. From 1894-1915 he taught violin and viola at the Royal College of Music in London. As a violinist he appeared not only as a soloist, but in a celebrated piano trio with Albeniz and the cellist Augustin Rubio. For the 1903-04 season he was a concertmaster of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, also appearing with the orchestra that year as soloist in the Mendelssohn concerto and playing a concert piece of his own {Tango, Opus 6, No. 3). His international conducting career included guest appearances with major orchestras on both sides of the Atlantic, including the BSO in 1929 and 1931; his 1929 program included two movements from his arrangement of Iberia, at that time just recently published. In 1932 he led the first Spanish performance of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring. Iberia's pieces typically begin with a dance pattern and later introduce a copla (vocal melody) , but show considerable freedom and variety of form in their fine structure. -

KEYNOTES the OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER of the EVANSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA LAWRENCE ECKERLING, MUSIC DIRECTOR American Romantics

VOL. 46, NO. 3 • MARCH 2015 KEYNOTES THE OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE EVANSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA LAWRENCE ECKERLING, MUSIC DIRECTOR American Romantics he third concert of the ESO’s 69th season, with its 2:30 PM ON Ttheme of the enduring appeal of Romanticism for SUNDAY MARCH 15, 2015 composers well into the 20th century, features three very well known American composers: Copland, Barber, and Hanson, plus a short piece by the Estonian Arvo Pärt. American Romantics Our concert opens with El Salón México by Aaron Copland demanded repayment of $500, which had been advanced (1900–1990). This 12 minute showpiece, premiered in to Barber. Having spent the advance on a European 1936, was the very first of Copland’s “populist” composi- vacation, Barber was forced to have a student at the Curtis tions in which he moved away from his previous Institute of Music perform the finale with only two hours of “modernist” style to an accessible tuneful style. Copland had practice, thereby proving that it was in fact “playable.” discovered the Mexico City dance hall of the title in 1932, ronicallyI perhaps, it is the lush romantic beauty of the first and consulted a collection of Mexican folk songs to lend two movements which has made this concerto the most authentic local color to this brilliantly orchestrated tone performed of all American concertos. picture. Howard Hanson (1896–1981) composed in a style even The austere spirituality of the music of Arvo Pärt provides more consistently Romantic than did Barber; in fact he titled a complete contrast to El Salón México. -

A Listening Guide for the Indispensable Composers by Anthony Tommasini

A Listening Guide for The Indispensable Composers by Anthony Tommasini 1 The Indispensable Composers: A Personal Guide Anthony Tommasini A listening guide INTRODUCTION: The Greatness Complex Bach, Mass in B Minor I: Kyrie I begin the book with my recollection of being about thirteen and putting on a recording of Bach’s Mass in B Minor for the first time. I remember being immediately struck by the austere intensity of the opening choral singing of the word “Kyrie.” But I also remember feeling surprised by a melodic/harmonic shift in the opening moments that didn’t do what I thought it would. I guess I was already a musician wanting to know more, to know why the music was the way it was. Here’s the grave, stirring performance of the Kyrie from the 1952 recording I listened to, with Herbert von Karajan conducting the Vienna Philharmonic. Though, as I grew to realize, it’s a very old-school approach to Bach. Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Vienna Philharmonic (12:17) Today I much prefer more vibrant and transparent accounts, like this great performance from Philippe Herreweghe’s 1996 recording with the chorus and orchestra of the Collegium Vocale, which is almost three minutes shorter. Philippe Herreweghe, conductor; Collegium Vocale Gent (9:29) Grieg, “Shepherd Boy” Arthur Rubinstein, piano Album: “Rubinstein Plays Grieg” (3:26) As a child I loved “Rubinstein Plays Grieg,” an album featuring the great pianist Arthur Rubinstein playing piano works by Grieg, including several selections from the composer’s volumes of short, imaginative “Lyrical Pieces.” My favorite was “The Shepherd Boy,” a wistful piece with an intense middle section.