Scratch Pad 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Politics and Metaphysics in Three Novels of Philip K. Dick

EUGÊNIA BARTHELMESS Politics and Metaphysics in Three Novels of Philip K. Dick Dissertação apresentada ao Curso de Pós- Graduação em Letras, Área de Concentra- ção Literaturas de Língua Inglesa, do Setor de Ciências Humanas, Letras e Artes da Universidade Federai do Paraná, como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Mestre. Orientadora: Prof.3 Dr.a BRUNILDA REICHMAN LEMOS CURITIBA 19 8 7 OF PHILIP K. DICK ERRATA FOR READ p -;2011 '6:€h|j'column iinesllll^^is'iiearly jfifties (e'jarly i fx|fties') fifties); Jl ' 1 p,.2Ò 6th' column line 16 space race space race (late fifties) p . 33 line 13 1889 1899 i -,;r „ i i ii 31 p .38 line 4 reel."31 reel • p.41 line 21 ninteenth nineteenth p .6 4 line 6 acien ce science p .6 9 line 6 tear tears p. 70 line 21 ' miliion million p .72 line 5 innocence experience p.93 line 24 ROBINSON Robinson p. 9 3 line 26 Robinson ROBINSON! :; 1 i ;.!'M l1 ! ! t i " i î : '1 I fi ' ! • 1 p .9 3 line 27 as deliberate as a deliberate jf ! •! : ji ' i' ! p .96 lin;e , 5! . 1 from form ! ! 1' ' p. 96 line 8 male dis tory maledictory I p .115 line 27 cookedly crookedly / f1 • ' ' p.151 line 32 why this is ' why is this I 1; - . p.151 line 33 Because it'll Because (....) it'll p.189 line 15 mourmtain mountain 1 | p .225 line 13 crete create p.232 line 27 Massachusetts, 1960. Massachusetts, M. I. T. -

Australian SF News 26

SNOW QUEEN Wins Hugo THE 1981 HUGO AWARDS were presented at THE BEST NON-FICTION Award went to Carl DENVENTION, 39th World Science Fiction Sagan's "Cosmos", the book based on Convention, held in Denver,Colorado , his TV series. THE BEST PROFESSIONAL on the Sunday evening of the 6th of EDITOR Award went to Edward L.Ferman, September. The BEST NOVEL AWARD went to editor of The Magazine of Fantasy and THE SNOW QUEEN by Joan Vinge. (Dial and Science Fiction. Michael Whelan won the Dell USA and Sidgwick & Jackson and BEST PROFESSIONAL ARTIST. BEST FANZINE Futura U.K.). Gordon R.Dickson won was again won by Locus. BEST FAN ARTIST both THE BEST NOVELLA and THE NOVELETTE AWARD went to Victoria Poyser. The late Awards with "Lost Dorsai" (Destinies Susan Wood was voted the BEST FAN WRITER February /March '80) and "The Cloak and Award. "The Empire Strikes Back" won the the Staff"(Analog - August '80). Co BEST DRAMATIC PRESENTATION Award. The Guest of Honor at the World Con with multi-talented Somtow Sucharitkul was C.L.Moore, Clifford D.Simak, won the the recipient of the JOHN W. CAMPBELL ?EST SHORT STORY Award with "Grotto of, Award for Best New Writer. JOAN VINGE the Dancing Deer" (Analog - April '80). Photo Jay K.Klein Baltimore To Hold 1983 - Melbourne Bids For 1985 BALTIMORE won the bid to hold the 1983 getting around to the various venues. World SF Convention. Australia put up One professional correspondent reports a very good show,but not good enough that it was a waste of money for her against the very strong bid by the and other editorial friends. -

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works of Speculative Fiction

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works Of Speculative Fiction About Catalogue XV Welcome to our 15th catalogue. It seems to be turning into an annual thing, given it was a year since our last catalogue. Well, we have 116 works of speculative fiction. Some real rarities in here, and some books that we’ve had before. There’s no real theme, beyond speculative fiction, so expect a wide range from early taproot texts to modern science fiction. Enjoy. About Us We are sellers of rare books specialising in speculative fiction. Our company was established in 2010 and we are based in Yorkshire in the UK. We are members of ILAB, the A.B.A. and the P.B.F.A. To Order You can order via telephone at +44(0) 7557 652 609, online at www.hyraxia.com, email us or click the links. All orders are shipped for free worldwide. Tracking will be provided for the more expensive items. You can return the books within 30 days of receipt for whatever reason as long as they’re in the same condition as upon receipt. Payment is required in advance except where a previous relationship has been established. Colleagues – the usual arrangement applies. Please bear in mind that by the time you’ve read this some of the books may have sold. All images belong to Hyraxia Books. You can use them, just ask us and we’ll give you a hi-res copy. Please mention this catalogue when ordering. • Toft Cottage, 1 Beverley Road, Hutton Cranswick, UK • +44 (0) 7557 652 609 • • [email protected] • www.hyraxia.com • Aldiss, Brian - The Helliconia Trilogy [comprising] Spring, Summer and Winter [7966] London, Jonathan Cape, 1982-1985. -

Selected Scifi 201102.Xlsx

Selected Used SciFi Books- Subject to availability - Call/email store to receive purchasing link ([email protected] 540206-2505) StorePri AuthorsLast Title EAN Publisher ce Cross-Currents: Storm Season, The Face of Chaos, Abbey, Robert Lynn Asprin and Lynn B000GPXLOQ Nelson Doubleday,. $8.00 and Wings of Omen Adams, Douglas Life, The Universe and Everything 9780517548745 Harmony Books $8.00 Adams, Douglas Mostly Harmless 9781127539635 BALLANTINE BOOKS $15.00 Adams, Douglas So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish 9780795326516 HARMONY BOOKS $6.00 Adams, Douglas The Restaurant at the End of the Universe 9780517545355 Harmony $8.00 Adams, Richard MAIA 9780394528571 Knopf $8.00 Alan, Foster Dean Midworld B001975ZFI Ballentine $8.00 Aldiss, Brian W. Helliconia Summer (Helliconia Trilogy, Book Two) 9781111805173 Atheneum / $8.00 Aldiss, Brian W. Non-Stop B0057JRIV8 Carroll & Graf $10.00 Aldiss, Brian Wilson Helliconia Winter (Helliconia, 3) 9780689115417 Atheneum $7.00 Allen, Roger E. Isaac Asimov's Inferno 9780441000234 Ace Trade $6.00 Allen, Roger Macbride Isaac Asimov's Utopia 9781857982800 Orion Publishing Co $8.00 Allston, Aaron Enemy lines (Star wars, The new Jedi order) 9780739427774 Science Fiction $15.00 Anderson, Kevin J and Rebecca The Rise of the Shadow Academy 9781568652115 Guild America $15.00 Moesta Anderson, Kevin J,Herbert, Brian Hunters of Dune 9780765312921 Tor Books $10.00 Anderson, Kevin J. A Forest of Stars: The Saga of Seven Suns Book 2 9780446528719 Aspect $8.00 Anderson, Kevin J. Darksaber (Star Wars) 9780553099744 Spectra $10.00 Anderson, Kevin J. Hidden Empire: The Saga of Seven Suns - Book 1 9780446528627 Aspect $8.00 Anderson, Kevin J. -

The Simulacra // Philip K. Dick

The Simulacra // Philip K. Dick 0547601301, 9780547601304 // 224 pages // Philip K. Dick // The Simulacra // 2011 // Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011 // On a ravaged Earth, fate and circumstances bring together a disparate group of characters, including a fascist with dreams of a coup, a composer who plays his instrument with his mind, a First Lady who calls all the shots, and the world’s last practicing therapist. And they all must contend with an underclass that is beginning to ask a few too many questions, aided by a man called Loony Luke and his very persuasive pet alien. In classic Philip K. Dick fashion, The Simulacra combines time travel, psychotherapy, telekinesis, androids, and Neanderthal-like mutants to create a rousing, mind-bending story where there are conspiracies within conspiracies and nothing is ever what it seems. file download dyguw.pdf Philip K. Dick // May 14, 2010 // ISBN:9780575098312 // 208 pages // A prophetic and unsettling chronicle detailing the rise and fall of a post-nuclear massiah, by the author of BLADE RUNNER and MINORITY REPORT Floyd Jones is sullen, ungainly // Fiction // The World Jones Made The pdf download The Simulacra pdf download Voices From the Street // Nov 13, 2007 // Philip K. Dick // Fiction // 304 pages // Stuart Hadley is a young radio electronics salesman in early 1950s Oakland, California. He has what many would consider the ideal life; a nice house, a pretty wife, a decent // ISBN:9781429920605 The Simulacra pdf 208 pages // Vintage PKD // Dec 18, 2007 // Philip K. Dick // A master of science fiction, a voice of the changing counterculture, and a genuine visionary, Philip K. -

Indice: 0. Philip K. Dick. Biografía. La Esquizofrenia De Dick. Antonio Rodríguez Babiloni 1

Indice: 0. Philip K. Dick. Biografía. La esquizofrenia de Dick. Antonio Rodríguez Babiloni 1. El cuento final de todos los cuentos. Philip K. Dick. 2. El impostor. Philip K. Dick. 3. 20 años sin Phil. Ivan de la Torre. 4. La mente alien. Philip K. Dick. 5. Philip K. Dick: ¿Aún sueñan los hombres con ovejas de carne y hueso? Jorge Oscar Rossi. 6. Podemos recordarlo todo por usted. Philip K. Dick. 7. Philip K. Dick en el cine 8. Bibliografía general de Philip K. Dick PHILIP K. DICK. BIOGRAFÍA. LA ESQUIZOFRENIA DE DICK. Antonio Rodríguez Babiloni Biografía: Philip. K. Dick (1928-1982) Nació prematuramente, junto a su hermana gemela Jane, el 2 de marzo 1928, en Chicago. Jane murió trágicamente pocas semanas después. La influencia de la muerte de Jane fue una parte dominante de la vida y obra de Philp K. Dick. El biógrafo Lawrence Sutin escribe; ...El trauma de la muerte de Jane quedó como el suceso central de la vida psíquica de Phil Dos años más tarde los padres de Dick, Dorothy Grant y Joseph Edgar Dick se mudaron a Berkeley. A esas alturas el matrimonio estaba prácticamente roto y el divorcio llegó en 1932, Dick se quedó con su madre, con la que se trasladó a Washington. En 1940 volvieron a Berkeley. Fue durante este período cuando Dick comenzó a leer y escribir ciencia ficción. En su adolescencia, publicó regularmente historias cortas en el Club de Autores Jovenes, una columna el Berkeley Gazette. Devoraba todas las revistas de ciencia-ficción que llegaban a sus manos y muy pronto empezó a ser influido por autores como Heinlein y Van Vogt. -

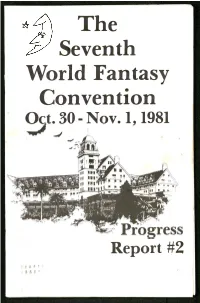

The Convention Itself

The Seventh World Fantasy Convention Oct. 30 - Nov. 1.1981 V ■ /n Jg in iiiWjF. ni III HITV Report #2 I * < ? I fl « f Guests of Honor Alan Garner Brian Frond Peter S. Beagle Master of Ceremonies Karl Edward Wagner Jack Rems, Jeff Frane, Chairmen Will Stone, Art Show Dan Chow, Dealers Room Debbie Notkin, Programming Mark Johnson, Bill Bow and others 1981 World Fantasy Award Nominations Life Achievement: Joseph Payne Brennan Avram Davidson L. Sprague de Camp C. L. Moore Andre Norton Jack Vance Best Novel: Ariosto by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro Firelord by Parke Godwin The Mist by Stephen King (in Dark Forces) The Shadow of the Torturer by Gene Wolfe Shadowland by Peter Straub Best Short Fiction: “Cabin 33” by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro (in Shadows 3) “Children of the Kingdom” by T.E.D. Klein (in Dark Forces) “The Ugly Chickens” by Howard Waldrop (in Universe 10) “Unicorn Tapestry” by Suzy McKee Charnas (in New Dimensions 11) Best Anthology or Collection: Dark Forces ed. by Kirby McCauley Dragons of Light ed. by Orson Scott Card Mummy! A Chrestomathy of Crypt-ology ed. by Bill Pronzini New Terrors 1 ed. by Ramsey Campbell Shadows 3 ed. by Charles L. Grant Shatterday by Harlan Ellison Best Artist: Alicia Austin Thomas Canty Don Maitz Rowena Morrill Michael Whelan Gahan Wilson Special Award (Professional) Terry Carr (anthologist) Lester del Rey (Del Rey/Ballantine Books) Edward L. Ferman (Magazine of Fantasy ir Science Fiction) David G. Hartwell (Pocket/Timescape/Simon & Schuster) Tim Underwood/Chuck Miller (Underwood & Miller) Donald A. Wollheim (DAW Books) Special Award (Non-professional) Pat Cadigan/Arnie Fenner (for Shayol) Charles de Lint/Charles R. -

New Human Needs

NEW HUMAN NEEDS A lesson from safe sci-fi futures Master´s Thesis in Futures Studies Author: Aleksej Nareiko Supervisors: Professor Markku Wilenius Professor Göte Nyman Postdoctoral Researcher Marja Turunen, D.Sc. (Tech) 19.03.2020 Turku The originality of this thesis has been checked in accordance with the University of Turku quality assurance system using the Turnitin Originality Check service. Turun kauppakorkeakoulu • Turku School of Economics Table of contents 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Story of the research idea ............................................................................... 5 1.2 Research objective and scope ......................................................................... 5 1.2.1 Key definitions ................................................................................... 6 1.2.2 Research question .............................................................................. 6 1.2.3 Epistemological and ontological stance of the researcher ................. 7 1.2.4 General outline of the research .......................................................... 9 1.3 Research gaps and originality of this research ............................................. 10 1.3.1 No futures research of human needs ................................................ 10 1.3.2 No framework or comprehensive typology of transformative changes for humankind .................................................................... 11 1.3.3 -

SCIENCE FICTION FALL T)T1T 7TT?TI7 NUMBER 48 1983 Mn V X J J W $2.00 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O

SCIENCE FICTION FALL T)T1T 7TT?TI7 NUMBER 48 1983 Mn V X J_J W $2.00 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O. BOX 11408 PORTLAND, OR 97211 AUGUST, 1983 —VOL.12, NO.3 WHOLE NUMBER 98 PHONE: (503) 282-0381 RICHARD E. GEIS—editor & publisher PAULETTE MINARE', ASSOCIATE EDITOR PUBLISHED QUARTERLY FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. SINGLE COPY - $2.00 ALIEN THOUGHTS BY THE EDITOR.9 THE TREASURE OF THE SECRET C0RDWAINER by j.j. pierce.8 LETTERS.15 INTERIOR ART-- ROBERT A. COLLINS CHARLES PLATT IAN COVELL E. F. BLEILER ALAN DEAN FOSTER SMALL PRESS NOTES ED ROM WILLIAM ROTLSER-8 BY THE EDITOR.92 KERRY E. DAVIS RAYMOND H. ALLARD-15 ARNIE FENNER RICHARD BRUNING-20199 RONALD R. LAMBERT THE VIVISECTOR ATOM-29 F. M. BUSBY JAMES MCQUADE-39 BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER.99 ELAINE HAMPTON UNSIGNED-35 J.R. MADDEN GEORGE KOCHELL-38,39,90,91 RALPH E. VAUGHAN UNSIGNED-96 ROBERT BLOCH TWONG, TWONG SAID THE TICKTOCKER DARRELL SCHWEITZER THE PAPER IS READY DONN VICHA POEMS BY BLAKE SOUTHFORK.50 HARLAN ELLISON CHARLES PLATT THE ARCHIVES BOOKS AND OTHER ITEMS RECEIVED OTHER VOICES WITH DESCRIPTION, COMMENTARY BOOK REVIEWS BY AND OCCASIONAL REVIEWS.51 KARL EDD ROBERT SABELLA NO ADVERTISING WILL BE ACCEPTED RUSSELL ENGEBRETSON TEN YEARS AGO IN SF - SUTER,1973 JOHN DIPRETE BY ROBERT SABELLA.62 Second Class Postage Paid GARTH SPENCER at Portland, OR 97208 THE STOLEN LAKE P. MATHEWS SHAW NEAL WILGUS ALLEN VARNEY Copyright (c) 1983 by Richard E. MARK MANSELL Geis. One-time rights only have ALMA JO WILLIAMS been acquired from signed or cred¬ DEAN R. -

The Sword of the Lictor

Wolfe,_Gene_-_Book_of_the_New_Sun_3_-_The_Sword_of_the_Lictor Books by Gene Wolfe Volume One—The Shadow of the Torturer Volume Two—The Claw of the Conciliator Volume Three—The Sword of the Lictor THE SWORD OF THE LICTOR Volume Three of The Book of the New Sun GENE WOLFE A TIMESCAPE BOOK PUBLISHED BY POCKET BOOKS NEW YORK This novel is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental. Another Original publication of TIMESCAPE BOOKS A Timescape Book published by file:///J|/sci-fi/Nieuwe%20map/Gene%20Wolfe%20-%20...Sun%203%20-%20The%20Sword%20of%20the%20Lictor.html (1 of 328)16-2-2006 16:06:59 Wolfe,_Gene_-_Book_of_the_New_Sun_3_-_The_Sword_of_the_Lictor POCKET BOOKS, a Simon & Schuster division of GULF & WESTERN CORPORATION 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, N.Y. 10020 Copyright © 1981 by Gene Wolfe Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 81-9427 All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Timescape Books, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, N.Y. 10020 ISBN: 0-671-45450-1 First Timescape Books paperback printing December, 1982 10 987654321 POCKET and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster. Use of the trademark TIMESCAPE is by exclusive license from Gregory Benford, the trademark owner. Printed in the U.S.A. Into the distance disappear the mounds of human heads. I dwindle—go unnoticed now. -

Tradução De David Soares

Tradução de David Soares 5 6 ÍNDICE DE UM CASTELO AO OUTRO Engenharia e Engenho na Ficção “Científica” de Philip K. Dick por Nuno Rogeiro Para a minha mulher Tessa e o meu fi lho Christopher,9 com um grande e tremendo amor. O HOMEM DO CASTELO ALTO por Philip K. Dick 59 7 8 DE UM CASTELO AO OUTRO Engenharia e Engenho na Ficção “Científica” de Philip K. Dick Nuno Rogeiro “Sonhámos o mundo. Sonhámo-lo fi rme, visível, ubíquo em espaço e durando no tempo. Mas na sua arquitectura permitimos ténues e eter- nas brechas de desrazão, que nos revelam ser o sonho falso”. Borges “O maior dos mágicos seria aquele capaz de lançar sobre si um feitiço tão completo, de forma a passar a tomar as suas fantasma- gorias por aparições autónomas. Não será este o nosso caso?” Novalis “Deus existe. Mas é difícil de encontrar.” Philip K. Dick “Tenho um amor secreto pelo Caos. Devia haver mais.” Ibid. 9 10 he Man in the High Castle foi traduzido em português, em primeiro lugar, pela colecção Argonauta (Livros do Brasil), em dois volumes. T O título escolhido foi O Homem do Castelo Alto. O livro estava ou esgotado, ou era difícil de encontrar. Foi-me pedido, para a presente edição, um estudo introdutório. De- cidi revisitar o que escrevi, há vinte e sete anos, para a revista Futuro Pre- sente. O texto, que procurava dedicar-se à obra e pensamento de Philip K. Dick, falecido no ano anterior, era o primeiro publicado em português. O retratado falecera com o aspecto físico de um Tolstoi, enredado numa vida paradoxal e misteriosa. -

SFRA Newsletter

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 6-1-2001 SFRA ewN sletter 252 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 252 " (2001). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 71. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/71 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #2S2 Ifay/June 200' Coeditors: Barbara Lucas Shelley Rodrjgo Blanctiard Nonfiction lerie lIeil Barron Fiction Ie riews: Shelley Rodrjgo Blancliard The SFRAReview (ISSN 1068-395X) is published six times a year by the Science Fiction ResearchAssociation (SFRA) and distI~bUld to SFRA mem bers.lndividual issues are not for sale. For information about the SFRA and its benefits, see the description at the back of this issue. For a membership application, contact SFRA Treasurer Dave Mead or get one from the SFRA website: <www.sfra.org>. SUBMISSIONS The SFRAReview editors encourage submissions, including essays, review essays that cover several related texts, and interviews. Please send submis sions or queries to both coeditors. If you would like to review nonfiction or fiction, please contact the respec tive editor and/or email [email protected]. Barbara Lucas, Coeditor 1352 Fox Run Drive, Suite 206 Willoughby, OH 44094 <[email protected]> Shelley Rodrigo Blanchard, Coeditor & Fiction Reviews Editor 6842 S.