Frieda Hennock: Her Views on Educational Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communication and Media Studies Department (CAMS) Department of Theatre and Dance Created

FOR ALUMNI & FRIENDS CONSTRUCTION COMMUNICATIONMANAGEMENT NEWS AND MEDIAISSUE STUDIES #10 WINTER 2020 SUMMER 2021 CAPS Becomes the Communication and Media Studies Department (CAMS) Department of Theatre and Dance Created On September 20, 2019 the “This change was prompted NMU Board of Trustees ap- by two things, those being proved an Academic Affairs ‘solid thinking’ on Provost Kerri restructuring plan that created Schuilling’s part, and ideas four divisions within the Col- from the faculty in theater and lege of Arts and Sciences. The dance themselves,” Cantrill Division of Visual and Perform- said. “It really was one of those ing Arts is now composed of a top-down, bottom-up kinds of new combined School of Mu- things.” sic, Theater and Dance, along with the established School of Although the former CAPS de- Art and Design. The Division of partment was reduced by about Social Sciences expanded to half the number of students and include: economics; communi- faculty, Cantrill assured students cations, broadcasting and jour- that it was an amicable parting. nalism; political science; and The two departments are still sociology and anthropology. co-located in the Thomas Fine The Communication and Arts building, and there remains Performance Studies (CAPS) department was split into two a great deal of collaboration and camaraderie. separate departments. According to Provost Kerri Schuiling, “this “This change was prompted by two In addition to theater and dance was all done to create efficiencies, things, those being “solid thinking” breaking off to its own department, enhance collaboration and facilitate public relations was moved to the cost savings over time.” on Provost Kerri Schuilling’s part, and College of Business. -

Stations Coverage Map Broadcasters

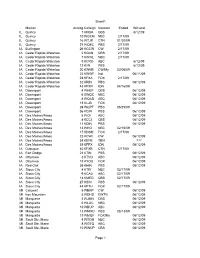

820 N. Capitol Ave., Lansing, MI 48906 PH: (517) 484-7444 | FAX: (517) 484-5810 Public Education Partnership (PEP) Program Station Lists/Coverage Maps Commercial TV I DMA Call Letters Channel DMA Call Letters Channel Alpena WBKB-DT2 11.2 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOOD-TV 7 Alpena WBKB-DT3 11.3 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOTV-TV 20 Alpena WBKB-TV 11 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WXSP-DT2 15.2 Detroit WKBD-TV 14 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WXSP-TV 15 Detroit WWJ-TV 44 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WXMI-TV 19 Detroit WMYD-TV 21 Lansing WLNS-TV 36 Detroit WXYZ-DT2 41.2 Lansing WLAJ-DT2 25.2 Detroit WXYZ-TV 41 Lansing WLAJ-TV 25 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WJRT-DT2 12.2 Marquette WLUC-DT2 35.2 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WJRT-DT3 12.3 Marquette WLUC-TV 35 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WJRT-TV 12 Marquette WBUP-TV 10 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WBSF-DT2 46.2 Marquette WBKP-TV 5 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City WEYI-TV 30 Traverse City-Cadillac WFQX-TV 32 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOBC-CA 14 Traverse City-Cadillac WFUP-DT2 45.2 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOGC-CA 25 Traverse City-Cadillac WFUP-TV 45 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOHO-CA 33 Traverse City-Cadillac WWTV-DT2 9.2 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOKZ-CA 50 Traverse City-Cadillac WWTV-TV 9 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOLP-CA 41 Traverse City-Cadillac WWUP-DT2 10.2 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOMS-CA 29 Traverse City-Cadillac WWUP-TV 10 GR-Kzoo-Battle Creek WOOD-DT2 7.2 Traverse City-Cadillac WMNN-LD 14 Commercial TV II DMA Call Letters Channel DMA Call Letters Channel Detroit WJBK-TV 7 Lansing WSYM-TV 38 Detroit WDIV-TV 45 Lansing WILX-TV 10 Detroit WADL-TV 39 Marquette WJMN-TV 48 Flint-Saginaw-Bay -

All Full-Power Television Stations by Dma, Indicating Those Terminating Analog Service Before Or on February 17, 2009

ALL FULL-POWER TELEVISION STATIONS BY DMA, INDICATING THOSE TERMINATING ANALOG SERVICE BEFORE OR ON FEBRUARY 17, 2009. (As of 2/20/09) NITE HARD NITE LITE SHIP PRE ON DMA CITY ST NETWORK CALLSIGN LITE PLUS WVR 2/17 2/17 LICENSEE ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX NBC KRBC-TV MISSION BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX CBS KTAB-TV NEXSTAR BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX FOX KXVA X SAGE BROADCASTING CORPORATION ABILENE-SWEETWATER SNYDER TX N/A KPCB X PRIME TIME CHRISTIAN BROADCASTING, INC ABILENE-SWEETWATER SWEETWATER TX ABC/CW (DIGITALKTXS-TV ONLY) BLUESTONE LICENSE HOLDINGS INC. ALBANY ALBANY GA NBC WALB WALB LICENSE SUBSIDIARY, LLC ALBANY ALBANY GA FOX WFXL BARRINGTON ALBANY LICENSE LLC ALBANY CORDELE GA IND WSST-TV SUNBELT-SOUTH TELECOMMUNICATIONS LTD ALBANY DAWSON GA PBS WACS-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY PELHAM GA PBS WABW-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY VALDOSTA GA CBS WSWG X GRAY TELEVISION LICENSEE, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ADAMS MA ABC WCDC-TV YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY NBC WNYT WNYT-TV, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY ABC WTEN YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY FOX WXXA-TV NEWPORT TELEVISION LICENSE LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY AMSTERDAM NY N/A WYPX PAXSON ALBANY LICENSE, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY PITTSFIELD MA MYTV WNYA VENTURE TECHNOLOGIES GROUP, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CW WCWN FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY PBS WMHT WMHT EDUCATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CBS WRGB FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. -

I. Tv Stations

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 In the Matter of ) ) MB Docket No. 17- WSBS Licensing, Inc. ) ) ) CSR No. For Modification of the Television Market ) For WSBS-TV, Key West, Florida ) Facility ID No. 72053 To: Office of the Secretary Attn.: Chief, Policy Division, Media Bureau PETITION FOR SPECIAL RELIEF WSBS LICENSING, INC. SPANISH BROADCASTING SYSTEM, INC. Nancy A. Ory Paul A. Cicelski Laura M. Berman Lerman Senter PLLC 2001 L Street NW, Suite 400 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (202) 429-8970 April 19, 2017 Their Attorneys -ii- SUMMARY In this Petition, WSBS Licensing, Inc. and its parent company Spanish Broadcasting System, Inc. (“SBS”) seek modification of the television market of WSBS-TV, Key West, Florida (the “Station”), to reinstate 41 communities (the “Communities”) located in the Miami- Ft. Lauderdale Designated Market Area (the “Miami-Ft. Lauderdale DMA” or the “DMA”) that were previously deleted from the Station’s television market by virtue of a series of market modification decisions released in 1996 and 1997. SBS seeks recognition that the Communities located in Miami-Dade and Broward Counties form an integral part of WSBS-TV’s natural market. The elimination of the Communities prior to SBS’s ownership of the Station cannot diminish WSBS-TV’s longstanding service to the Communities, to which WSBS-TV provides significant locally-produced news and public affairs programming targeted to residents of the Communities, and where the Station has developed many substantial advertising relationships with local businesses throughout the Communities within the Miami-Ft. Lauderdale DMA. Cable operators have obviously long recognized that a clear nexus exists between the Communities and WSBS-TV’s programming because they have been voluntarily carrying WSBS-TV continuously for at least a decade and continue to carry the Station today. -

Federal Register/Vol. 86, No. 91/Thursday, May 13, 2021/Proposed Rules

26262 Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 91 / Thursday, May 13, 2021 / Proposed Rules FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS BCPI, Inc., 45 L Street NE, Washington, shown or given to Commission staff COMMISSION DC 20554. Customers may contact BCPI, during ex parte meetings are deemed to Inc. via their website, http:// be written ex parte presentations and 47 CFR Part 1 www.bcpi.com, or call 1–800–378–3160. must be filed consistent with section [MD Docket Nos. 20–105; MD Docket Nos. This document is available in 1.1206(b) of the Commission’s rules. In 21–190; FCC 21–49; FRS 26021] alternative formats (computer diskette, proceedings governed by section 1.49(f) large print, audio record, and braille). of the Commission’s rules or for which Assessment and Collection of Persons with disabilities who need the Commission has made available a Regulatory Fees for Fiscal Year 2021 documents in these formats may contact method of electronic filing, written ex the FCC by email: [email protected] or parte presentations and memoranda AGENCY: Federal Communications phone: 202–418–0530 or TTY: 202–418– summarizing oral ex parte Commission. 0432. Effective March 19, 2020, and presentations, and all attachments ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking. until further notice, the Commission no thereto, must be filed through the longer accepts any hand or messenger electronic comment filing system SUMMARY: In this document, the Federal delivered filings. This is a temporary available for that proceeding, and must Communications Commission measure taken to help protect the health be filed in their native format (e.g., .doc, (Commission) seeks comment on and safety of individuals, and to .xml, .ppt, searchable .pdf). -

List of Directv Channels (United States)

List of DirecTV channels (United States) Below is a numerical representation of the current DirecTV national channel lineup in the United States. Some channels have both east and west feeds, airing the same programming with a three-hour delay on the latter feed, creating a backup for those who missed their shows. The three-hour delay also represents the time zone difference between Eastern (UTC -5/-4) and Pacific (UTC -8/-7). All channels are the East Coast feed if not specified. High definition Most high-definition (HDTV) and foreign-language channels may require a certain satellite dish or set-top box. Additionally, the same channel number is listed for both the standard-definition (SD) channel and the high-definition (HD) channel, such as 202 for both CNN and CNN HD. DirecTV HD receivers can tune to each channel separately. This is required since programming may be different on the SD and HD versions of the channels; while at times the programming may be simulcast with the same programming on both SD and HD channels. Part time regional sports networks and out of market sports packages will be listed as ###-1. Older MPEG-2 HD receivers will no longer receive the HD programming. Special channels In addition to the channels listed below, DirecTV occasionally uses temporary channels for various purposes, such as emergency updates (e.g. Hurricane Gustav and Hurricane Ike information in September 2008, and Hurricane Irene in August 2011), and news of legislation that could affect subscribers. The News Mix channels (102 and 352) have special versions during special events such as the 2008 United States Presidential Election night coverage and during the Inauguration of Barack Obama. -

Number of Markets Cleared: 210 208 188 194 4 209 205 204 167 Percent of Households Cleared: 100.0% 99.3% 97.6% 97.9% 12.3% 99.7% 97.3% 97.6% 75.4%

NUMBER OF MARKETS CLEARED: 210 208 188 194 4 209 205 204 167 PERCENT OF HOUSEHOLDS CLEARED: 100.0% 99.3% 97.6% 97.9% 12.3% 99.7% 97.3% 97.6% 75.4% 175 198 194 195 203 170 197 128 201 DR. OZ 3RD QUEEN QUEEN MIND OF A SEINFELD 4TH SEINFELD 5TH DR. OZ CYCLE LATIFAH LATIFAH MAN CYCLE CYCLE KING 2nd Cycle KING 3rd Cycle RANK MARKET %US REP 2011-2014 2014-2015 2013-2014 2014-2015 2015-2016 4th Cycle 5th Cycle 2nd Cycle 3rd Cycle 1 NEW YORK NY 6.44% PM WNYW WNYW/WWOR WCBS/WLNY WCBS/WLNY WPIX WPIX WPIX WCBS/WLNY WCBS/WLNY 2 LOS ANGELES CA 4.89% ES KABC KCOP/KTTV KCAL/KCBS KCAL/KCBS KCOP/KDOC/KTTV KCOP/KDOC/KTTV KCOP/KTTV KCOP/KTTV 3 CHICAGO IL 3.05% ZH WFLD WFLD/WPWR WBBM/WCIU WBBM WCIU WCIU/WWME WCIU WCIU 4 PHILADELPHIA PA 2.56% PM WTXF WTXF KYW/WPSG KYW/WPSG KYW/WPSG KYW/WPSG KYW/WPSG KYW/WPSG 5 DALLAS-FT WORTH TX 2.29% JM KFWD/WFAA KDFI/KDFW KTVT/KTXA KTVT/KTXA KDAF KDAF KDAF KTVT/KTXA KTVT/KTXA 6 SAN FRANCISCO-OAKLAND-SAN JOSE CA 2.18% ES KICU/KTVU KICU/KTVU KBCW/KPIX KBCW/KPIX KICU/KTVU KICU/KTVU KBCW/KPIX KBCW/KPIX 7 BOSTON (MANCHESTER) MA 2.10% PM WFXT WFXT WBZ/WSBK WBZ/WSBK WBZ/WSBK WBZ/WSBK WBZ/WSBK WBZ/WSBK 8 WASHINGTON (HAGERSTOWN) DC 2.08% PM WTTG WDCA/WTTG WJLA WJLA WDCW WDCW WJAL 9 ATLANTA GA 2.05% JM WAGA WSB WUPA WUPA WPCH WPCH WPCH WPCH 10 HOUSTON TX 1.98% JM KPRC KRIV/KTXH KPRC KPRC KIAH KIAH KUBE KRIV/KUBE KUBE 11 DETROIT MI 1.60% ZH WXYZ WXYZ WKBD/WWJ WKBD/WWJ WKBD/WWJ WMYD WADL WKBD/WWJ WKBD/WWJ 12 PHOENIX AZ 1.60% ES KTVK KSAZ/KUTP KASW/KTVK KASW/KTVK KAZT KAZT KASW/KTVK KASW/KTVK 13 SEATTLE-TACOMA WA 1.60% ES KOMO/KOMO-DT2 -

01 Reporter 07-11-12.Indd

RRONON OOUNTYUNTY EEPORTERPORTER.CCOMOM SERVINGI ALL OF MICHIGAN’S C IRON COUNTY R & SURROUNDING AREAS Wednesday, July 11, 2012 • 127th Year, Number 46 • Iron River Publications, Inc. P.O. Box 311, Iron River, Michigan 49935 --Section 1 -- Price $1.00 Fine Arts Show opens July 30 at IC Museum CASPIAN—The Arts Commit- as well as pen, pencil or charcoal tee at the Iron County Museum drawings, sketches, photogra- here has announced the 40th an- phy, sculpturing, wood carvings nual Fine Arts Show will open and basket making. Monday, July 30. A printed entry form should On the fi nal two days, Fri- be fi led no later than July 20 so day and Saturday, Aug. 3 and the committee can plan display 4, a “Starving Artist” sale will space. be held with added pieces of art For the show itself, artists are available to sell. restricted to showing art that has Blanks to register for the been done within the past year show will be available at the mu- or art that has never been shown seum desk, or information may before. be given to desk personnel over All care possible is taken, the telephone. and artists are encouraged to Blanks will also be available staff their own exhibit the last beginning this week at Central two days when many additional Arts and Gifts and the West Iron items may be brought in. District Library in Iron River, the For the sale, artists may bring Crystal Falls Contemporary Cen- in the additional sales pieces on ter and the Crystal Falls District Thursday before the museum’s Community Library in Crystal 10 a.m. -

Television Channel Fcc Assignments for Us Channel Repacking (To Channels Less Than 37)

TELEVISION CHANNEL FCC ASSIGNMENTS FOR US CHANNEL REPACKING (TO CHANNELS LESS THAN 37) March 29, 2017 LEGEND FINAL TELEVISION CHANNEL ASSIGNMENT INFORMATION RELATED TO INCENTIVE AUCTION REPACKING Technical Parameters for Post‐Auction Table of Allotments NOTE: These results are based on the 20151020UCM Database, 2015Oct_132Settings.xml study template, and TVStudy version 1.3.2 (patched) FacID Site Call Ch PC City St Lat Lon RCAMSL HAAT ERP DA AntID Az 21488 KYES‐TV 5 5 ANCHORAGE AK 612009 1493055 614.5 277 15 DA 93311 0 804 KAKM 8 8 ANCHORAGE AK 612520 1495228 271.2 240 50 DA 67943 0 10173 KTUU‐TV 10 10 ANCHORAGE AK 612520 1495228 271.2 240 50 DA 89986 0 13815 KYUR 12 12 ANCHORAGE AK 612520 1495228 271.2 240 41 DA 68006 0 35655 KTBY 20 20 ANCHORAGE AK 611309 1495332 98 45 234 DA 90682 0 49632 KTVA 28 28 ANCHORAGE AK 611131 1495409 130.6 60.6 28.9 DA 73156 0 25221 KDMD 33 33 ANCHORAGE AK 612009 1493056 627.9 300.2 17.2 DA 102633 0 787 KCFT‐CD 35 35 ANCHORAGE AK 610400 1494444 539.7 0 15 DA 109112 315 64597 KFXF 7 7 FAIRBANKS AK 645518 1474304 512 268 6.1 DA 91018 0 69315 KUAC‐TV 9 9 FAIRBANKS AK 645440 1474647 432 168.9 30 ND 64596 K13XD‐D 13 13 FAIRBANKS AK 645518 1474304 521.6 0 3 DA 105830 170 13813 KATN 18 18 FAIRBANKS AK 645518 1474258 473 230 16 ND 49621 KTVF 26 26 FAIRBANKS AK 645243 1480323 736 471 27 DA 92468 110 8651 KTOO‐TV 10 10 JUNEAU AK 581755 1342413 37 ‐363 1 ND 13814 KJUD 11 11 JUNEAU AK 581804 1342632 82 ‐290 0.14 DA 78617 0 60520 KUBD 13 13 KETCHIKAN AK 552058 1314018 100 ‐71 0.413 DA 104820 0 20015 KJNP‐TV 20 20 NORTH -

Sheet1 Page 1 Market Analog Callsign Network Ended Will End IL

Sheet1 Market Analog Callsign Network Ended Will end IL Quincy 7 KHQA CBS 6/12/09 IL Quincy 10 WGEM NBC 2/17/09 IL Quincy 16 WTJR CTN 01/20/09 IL Quincy 27 WQEC PBS 2/17/09 IA Burlington 26 KGCW CW 2/17/09 IA Cedar Rapids-Waterloo 2 KGAN CBS 2/17/09 IA Cedar Rapids-Waterloo 7 KWWL NBC 2/17/09 IA Cedar Rapids-Waterloo 9 KCRG ABC 6/12/09 IA Cedar Rapids-Waterloo 12 KIIN PBS 6/12/09 IA Cedar Rapids-Waterloo 20 KWKB CW/My 02/06/09 IA Cedar Rapids-Waterloo 22 KWWF Ind. 06/11/09 IA Cedar Rapids-Waterloo 28 KFXA FOX 2/17/09 IA Cedar Rapids-Waterloo 32 KRIN PBS 06/12/09 IA Cedar Rapids-Waterloo 48 KPXR ION 04/16/09 IA Davenport 4 WHBF CBS 06/12/09 IA Davenport 6 KWQC NBC 06/12/09 IA Davenport 8 WQAD ABC 06/12/09 IA Davenport 18 KLJB FOX 06/12/09 IA Davenport 24 WQPT PBS 05/25/09 IA Davenport 36 KQIN PBS 06/12/09 IA Des Moines/Ames 5 WOI ABC 06/12/09 IA Des Moines/Ames 8 KCCI CBS 06/12/09 IA Des Moines/Ames 11 KDIN PBS 06/12/09 IA Des Moines/Ames 13 WHO NBC 02/16/09 IA Des Moines/Ames 17 KDSM FOX 2/17/09 IA Des Moines/Ames 23 KCWI CW 06/12/09 IA Des Moines/Ames 34 KEFB TBN ??? IA Des Moines/Ames 39 KFPX ION 06/12/09 IA Dubuque 40 KFXB CTN 2/17/09 IA Fort Dodge 21 KTIN PBS 06/12/09 IA Ottumwa 3 KTVO ABC 06/12/09 IA Ottumwa 15 KYOU FOX 06/12/09 IA Red Oak 36 KHIN PBS 06/12/09 IA Sioux City 4 KTIV NBC 02/17/09 IA Sioux City 9 KCAU ABC 02/17/09 IA Sioux City 14 KMEG CBS 02/17/09 IA Sioux City 27 KSIN PBS 06/12/09 IA Sioux City 44 KPTH FOX 02/17/09 MI Calumet 5 WBKP CW 06/12/09 MI Iron Mountain 8 WDHS EWTN 06/12/09 MI Marquette 3 WJMN CBS 06/12/09 MI Marquette 6 WLUC NBC 06/12/09 MI Marquette 10 WBUP ABC 06/12/09 MI Marquette 13 WNMU PBS 05/13/09 MI Marquette 19 WMQF FOX/My 06/12/09 MI Sault Ste. -

2019 Norway Channel Lineup Due to Forces Beyond Our Control, Some Channels May Be Added, Moved, Or Changed Over a Period of Time

Due to forces beyond our control, some channels may be added, 2019 Norway Channel Lineup moved, or changed over a period of time. Basic TV Premium Packages $25/mo. (city), $27/mo. (twp) . 2.1 GUIDE Channel Guide Digital Basic Package 3.1 WJMN CBS Escanaba (+$25/mo.) HBO Package (+$22/mo.) 3.2 ESCP Escape 3.3 LAFF LAFF 100 TNCK The N (Nick GAS) 3.4 BOUN BOUNCE 101 NTOON Nick Toons 180 HBO-E HBO 4.1 TWC The Weather Channel 103 DISCF Discovery Family 181 HBO2 HBO 2 5.1 WBUP CW Marquette 110 DESTD Destination Discovery 182 HBOFE HBO Family 6.1 WLUC TV6/NBC Marquette 111 VELOC Velocity TV 183 HBOCM HBO Comedy 6.3 GRIT GRIT TV 112 COOK Cooking Channel 184 HBOZN HBO Zone 7.1 LOCAL Local Access Channel 114 DLIF Discovery Life Cinemax Package (+$16/mo.) 118 FYI For Your Inspiration 8.1 SCH School Channel 190 MAX-E Cinemax 119 H2 History International 9.1 WGNA WGN Chicago 191 AMAX Action Max 120 AHC American Hero’s Network 10.1 WBUP ABC Marquette 192 MMAX More Max e 1 e 134 BBC BBC America 11.1 WLUK FOX-Green Bay 193 TMAX Thriller Max 135 IFC Independent Film Channel 12.1 FOXUP Fox UP STARZ Package (+$15/mo.) 13.1 WNMU PBS Marquette 139 FXMC FX Movie Channel 140 NGW National Geographic Wild 220 STZEN STARZ ENCORE Packag 13.2 WNMU PBS–Kids 221 STZAC STARZ ENCORE Action 13.3 WNMU PBS-HD 145 LMN Lifetime Movie Network 222 STZBK STARZ ENCORE Black 14.1 HSN Home Shopping Network 149 MTVH MTV Hits Requiresrentalof digital or DVRBox 223 STZCL STARZ ENCORE Classic 150 CMTP CMT Pure Country 15.1 CSPAN C-SPAN - 224 STZSU STARZ ENCORE Suspense 16.1 CSPAN2 C-SPAN2 151 MTV2 MTV2 225 STZWS STARZ ENCORE Westerns 17.1 QVC QVC 152 MTV CL MTV Classic 230 STARZ STARZ E 18.1 EWTN Eternal Word TV Network 153 GAC Great American Country 231 STXCI STARZ Cinema E 19.1 TBN Trinity Broadcast Network 168 SEC SEC Network 169 ESPNU ESPN U Package4 232 STZ C STARZ Comedy E Extended Basic TV 170 ESPNCL ESPN Classic 233 STZ E STARZ Edge E $75/mo. -

Annual EEO Public File Report Form WBUP-TV and WBKP-TV Period

Annual EEO Public File Report Form WBUP-TV and WBKP-TV Period Covered June 1, 2020 – May 31, 2021 Full-Time Vacancies: Job Title Hire Date Source of Hire # of Interviews Community 8-5-20 Rehired former employee 1 Liason/Account executive Account Executive 8-17-20 Indeed.com 3 Reporter/Anchor 9-7-20 Indeed.com 2 Reporter/Anchor 9-21-20 Indeed.com 3 News Director 1-4-21 Indeed.com 2 Sports Director 1-11-21 Indeed.com 2 Reporter/Anchor 2-22-21 Indeed.com 3 Reporter/Anchor 3-1-21 Indeed.com 3 Reporter/Anchor 3-5-21 Indeed.com 4 Account Executive 5/17/21 Indeed.com 5 Recruitment Sources: Source Address/Phone # Website # of Interviews 819 N. Washington Michigan Association Ave. Lansing, MI 48906 www.michmab.com 0 of Broadcasters (800) 968-7622 Indeed.com www.indeed.com 27 Handshake www.joinhandshake.com 0 Tvjobs.com Tvjobs.com 0 Career Fairs: Source Address/Phone # Date MABF Virtual Media Career & 333 E Michigan Ave, Lansing, MI 3/9/21 Networking Event 48933 Scholarships: Scholarship Name Value The Robert Race Scholarship $1000 WBKP-TV/WBUP-TV/WBKB-TV/WOLV-FM/WCCY-AM/WHKB-FM and The Stephen A. $1000 Marks Foundation, Inc. Scholarship March 18, 2021 Kenn Baynard Lake Superior Community Broadcasting 1705 Ash St. Suite 5 Ishpeming, MI 49849 Dear Kenn Baynard: Thank you for your participation in the 2021 MAB Foundation Virtual Media Career & Networking Event on March 9, 2021 online during the Un-Conventional Great Lakes Media Show! We had 98 students and business-minded professionals register to attend this year’s virtual career event.