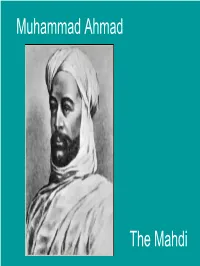

Al-Imam Al-Mahdi Muhammad Ahmad B. 'Abd Allah (1844-1885)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sudan, Imperialism, and the Mahdi's Holy

bria_29_3:Layout 1 3/14/2014 6:41 PM Page 6 bria_29_3:Layout 1 3/14/2014 6:41 PM Page 7 the rebels. Enraged mobs rioted in the Believing these victories proved city and killed about 50 Europeans. that Allah had blessed the jihad, huge SUDAN, IMPERIALISM, The French withdrew their fleet, but numbers of fighters from Arab tribes the British opened fire on Alexandria swarmed to the Mahdi. They joined AND THE MAHDI’SHOLYWAR and leveled many buildings. Later in his cause of liberating Sudan and DURING THE AGE OF IMPERIALISM, EUROPEAN POWERS SCRAMBLED TO DIVIDE UP the year, Britain sent 25,000 troops to bringing Islam to the entire world. AFRICA. IN SUDAN, HOWEVER, A MUSLIM RELIGIOUS FIGURE KNOWN AS THE MAHDI Egypt and easily defeated the rebel The worried Egyptian khedive and LED A SUCCESSFUL JIHAD (HOLY WAR) THAT FOR A TIME DROVE OUT THE BRITISH Egyptian army. Britain then returned British government decided to send AND EGYPTIANS. the government to the khedive, who Charles Gordon, the former governor- In the late 1800s, many European Ali established Sudan’s colonial now was little more than a British general of Sudan, to Khartoum. His nations tried to stake out pieces of capital at Khartoum, where the White puppet. Thus began the British occu- mission was to organize the evacua- Africa to colonize. In what is known and Blue Nile rivers join to form the pation of Egypt. tion of all Egyptian soldiers and gov- as the “scramble for Africa,” coun- main Nile River, which flows north to While these dramatic events were ernment personnel from Sudan. -

Updated List Is Attached to This Letter

TERRORISM U.S. Department of the Treasury Office of Foreign Assets Control What WhatYou YouNeed Need To To Know Know AboutAbout U.S. The Sanctions U.S. Embargo Executive Order 13224 blocking Terrorist Property and a summary of the Terrorism Sanctions Regulations (Title 31 Part 595 of the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations), Terrorism List Governments Sanctions Regulations (Title 31 Part 596 of the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations), and Foreign Terrorist Organizations Sanctions Regulations (Title 31 Part 597 of the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations) EXECUTIVE ORDER 13224 - BLOCKING PROPERTY AND PROHIBITING TRANSACTIONS WITH PERSONS WHO COMMIT, THREATEN TO COMMIT, OR SUPPORT TERRORISM By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, including the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (50 U.S.C. 1701 et seq.)(IEEPA), the National Emergencies Act (50 U.S.C. 1601 et seq.), section 5 of the United Nations Participation Act of 1945, as amended (22 U.S.C. 287c) (UNPA), and section 301 of title 3, United States Code, and in view of United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1214 of December 8, 1998, UNSCR 1267 of October 15, 1999, UNSCR 1333 of December 19, 2000, and the multilateral sanctions contained therein, and UNSCR 1363 of July 30, 2001, establishing a mechanism to monitor the implementation of UNSCR 1333, I, GEORGE W. BUSH, President of the United States of America, find that grave acts of terrorism and threats of terrorism committed by foreign terrorists, including -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the-deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Leaming 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI* ESCHATOLOGY AS POLITICS, ESCHATOLOGY AS THEORY: MODERN SUNNI ARAB MAHDISM IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Timothy R. Furnish, M.A.R. The Ohio State University 2001 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Jane Hathaway, Adviser Professor Sam Meier viser Professor Joseph Zeidan " Department of Histdry UMI Number: 3011060 UMI UMI Microform 3011060 Copyright 2001 by Bell & Howell Information and Leaming Company. -

The Sudanese Mahdi: Frontier Fundmentalist Author(S): John Voll Source: International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol

The Sudanese Mahdi: Frontier Fundmentalist Author(s): John Voll Source: International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 10, No. 2 (May, 1979), pp. 145-166 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/162124 Accessed: 07/11/2010 21:37 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=cup. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Journal of Middle East Studies. http://www.jstor.org Int. J. Middle East Stud. 10 (I979), I45-I66 Printed in Great Britain '45 John Voll THE SUDANESE MAHDI: FRONTIER FUNDMENTALIST The Sudanese Mahdi has been pictured as a villain, as a hero, as a reactionary, as an anti-imperialist revolutionary, and in many other ways. -

Mohammed Ahmed

Muhammad Ahmad The Mahdi Introducing Muhammad… • Muhammad Ahmad is the most influential man in Sudanese history • Born in 1844, he grew up in the Dongola region of the Sudan. • His father and brothers were boat builders but his grandfather was a fiki (religious teacher). • Mohammed learned to read and write from his grandfather, and devoted his life to religious study. He moved to the Isle of Abba to receive further religious instruction. • In 1881, Muhammad declared himself the ‘Mahdi’. Mahdi : “he who is guided aright” • It was predicted that spiritual ruler would appear who was destined to establish a reign of righteousness throughout the world. ABOUT THE SUDAN • Historically, the Sudan region was divided in many tribal groups. •The tribes made a living off the land. The fertile Nile Valley and the abundant rainfall in the southern territory makes cultivation possible. •Trade routes between the region and the rest of Africa, primarily Egypt, formed to facilitate the trade of gold, wood, ivory, gum, ostrich feathers and slaves. • Arab Muslim migration along trade routes in the 13th to 15th centuries allowed for the Islamicization of large portions of the Sudan regions. • Egypt invaded the Sudan in 1821 in order to obtain access to gold, ivory and slaves to subsidize the expansion and modernization of the Egyptian military. Conceptualizing ME&A Muhammad the Prophet… • After moving to the Isle of Abba, Muhammad built a mosque and was venerated as a holy man by all who knew him. • In 1881, he claimed that the prophet “Mohamed came to him in a dream and informed him, as from God, that he was the long- promised Mahdi” (False Prophet Article) • The Mahdi advocated purifying the Muslim faith. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Islam and the legitimation of power: the Mahdi-revolt in the Sudan Peters, R. Publication date 1983 Document Version Final published version Published in Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Peters, R. (1983). Islam and the legitimation of power: the Mahdi-revolt in the Sudan. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, Supplement(21), 409-420. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:06 Oct 2021 sj^cv.-c.c^^ .H--^; - ^. cV-v'v'^- .^ FACHGRUPPE 14: MODERNER VORDERER ORIENT LEITUNG: BABER JOHANSEN, BERLIN ISLAM AND THE LEGITIMATION OF POWER: THE MAHDl-REVOLT IN THE SUDAN* By Rudolf Peters, Amsterdam The authority of any state is, in the last instance, founded on physical force. -

The Mahdi's Legal Opinion As an Instrument of Reform

CHAPTER 4 The Mahdi’s Legal Opinion as an Instrument of Reform Issues in Divorce, Inheritance, False Accusation of Unlawful Intercourse and Homicide Aharon Layish Introduction1 Muhammad Ahmad b. ʿAbdallah (1844–85) headed, as a self-proclaimed Mahdi, a millenarian, revival and reformist movement in Islam in the late nineteenth century, strongly inspired by Salafi ideas and Sufi traditions that formed the social and intellectual background of his formative period.2 The Mahdi’s vision was to restore the theocracy of the Prophet Muhammad and the “Righteous Caliphs” in Sudan. He claimed legitimacy on the grounds of being a successor to Muhammad, his ability to communicate with him, and his infal- libility and moral authority. The Mahdi nominated successors to the orthodox caliphs, governors, military commanders and judges (qadis). Adherents to the Mahdiyya had to take a pledge of allegiance (bayʿa) entailing a commitment to 1 This paper is part of a comprehensive study entitled “Revival of Islamic Law in the Late 19th- Century Sudan: The Mahdi’s Legal Methodology and Its Application” (in progress) based on the Mahdi’s documents. I am most grateful to the late Prof. P.M. Holt who graciously placed his personal collection of the Mahdi’s documents at my disposal during my sabbatical stay in Oxford in 1993. I am indebted to Ruud Peters of the University of Amsterdam for allowing me to consult in manuscript form chapters on Islamic family law (see bibl.). Gaby Warburg has initiated me into Sudanese studies and was very helpful in various ways for which he deserves my sincere thanks. -

13.11.2001 — 004.001 — 1 B Council Regulation (Ec)

2001R0467 — EN — 13.11.2001 — 004.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 467/2001 of 6 March 2001 prohibiting the export of certain goods and services to Afghanistan, strengthening the flight ban and extending the freeze of funds and other financial resources in respect of the Taliban of Afgha- nistan, and repealing Regulation (EC) No 337/2000 (OJ L 67, 9.3.2001, p. 1) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Commission Regulation (EC) No 1354/2001 of 4 July 2001 L 182 15 5.7.2001 ►M2 Commission Regulation (EC) No 1996/2001 of 11 October 2001 L 271 21 12.10.2001 ►M3 Commission Regulation (EC) No 2062/2001 of 19 October 2001 L 277 25 20.10.2001 ►M4 Commission Regulation (EC) No 2199/2001 of 12 November 2001 L 295 16 13.11.2001 2001R0467 — EN — 13.11.2001 — 004.001 — 2 ▼B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 467/2001 of 6 March 2001 prohibiting the export of certain goods and services to Afghanistan, strengthening the flight ban and extending the freeze of funds and other financial resources in respect of the Taliban of Afghanistan, and repealing Regulation (EC) No 337/2000 THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, and in particular Articles60 and 301 thereof, Having regard to Council Common Position 2001/154/CFSP of 26 February 2001 concerning additional restrictive measures against the Taliban and amending Common Position 96/746/CFSP (1), Having regard to the proposal from the Commission, Whereas: (1) On 19 December 2000, the United NationsSecurity Council adopted Resolution 1333 (2000) demanding, inter alia, that the Taliban comply with Resolution 1267 (1999), in particular by ceasing to provide sanctuary and training for international terror- ists and their organisations and by handing over Usama Bin Ladin to the relevant authoritiesfor trial. -

Muhammad Ahmad Salam Al-Khatib , Muhamma

SECRET 20330512 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE STATES COMMAND HEADQUARTERS , JOINT TASK FORCE GUANTANAMO U.S. NAVAL STATION , GUANTANAMO BAY , CUBA APOAE09360 JTF- GTMO- CDR 12 May 2008 MEMORANDUMFORCommander, UnitedStates SouthernCommand, 3511NW 91st Avenue, Miami, FL 33172 SUBJECT Recommendationfor ContinuedDetentionUnderDoDControl(CD) for GuantanamoDetainee, ISN 000689DP(S) JTF - GTMO Detainee Assessment 1. ( S) Personal Information : JDIMS/NDRC ReferenceName: Mohammed Akhmed Salam al-Hatabi Current/ True Name and Aliases: Muhammad Ahmad Salam al-Khatib , Muhammad Ahmad Salam Muhammad al- Alaoui, Muhammad Ahmad Hitam al-Sulaybi,Muhammad Ahmad Salem Taizi, Muhammad Sallan, Hammad Salem , Harith al Taizi Place of Birth: Taiz, Yemen (YM ) Date ofBirth: 1 October 1980 Citizenship: Yemen Internment Serial Number (ISN) : -000689DP 2. (U// FOUO) Health: Detainee is in overall good health . 3. ( U ) JTF- GTMO Assessment : a. (S) Recommendation : JTF-GTMO recommends this detainee for Continued Detention Under Control (CD) . JTF-GTMO previously recommended detainee for Continued Detention Under DoD Control (CD) on 28 June 2006. b . (S ) Executive Summary: Detainee is assessed to be a member ofal-Qaida. Detainee is further assessed to be a member of a Faisalabad, Pakistan (PK) cell created by senior al-Qaida facilitator Zayn al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn, aka (Abu Zubaydah ), ISN -010016DP (GZ- 10016), and al- Qaida military operations commander NashwanAbd CLASSIFIED BY : MULTIPLE SOURCES REASON : E.O. 12958, AS AMENDED , SECTION 1.4 ( C DECLASSIFY ON 20330512 SECRET NOFORN 20330512 SECRET / NOFORN 20330512 JTF - GTMO -CDR SUBJECT : Recommendation for Continued Detention Under DoD Control (CD) for Guantanamo Detainee , ISN - 000689DP (S ) al-Razzaq Abd al-Baqi, aka ( Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi), ISN US9IZ -010026DP ( -10026 , with the purpose of returning to Afghanistan to conduct remote controlled improvised explosive devices (IED) att against US and Coalition forces. -

G.N. 261 United Nations Sanctions Ordinance

G.N. 261 UNITED NATIONS SANCTIONS ORDINANCE (Chapter 537) Pursuant to section 19 of the United Nations Sanctions (Afghanistan) (Arms Embargoes) Regulation (Chapter 537 sub. leg.), the Chief Executive the Honourable TUNG Chee Hwa has authorized the publication of the following designation of persons and entities as persons connected with Usama bin Laden by the Committee of the Security Council of the United Nations established pursuant to Resolution 1267. This new list supersedes all previous lists gazetted earlier under section 19 of the Regulation. Individuals: Abd Al-Hadi Al-Iraqi (a.k.a. Abu Abdallah, Abdal Al-Hadi Al-Iraqi) Abdul Rahman Yasin (A.K.A. Taha, Abdul Rahman S.; A.K.A. Taher, Abdul Rahman S.; A.K.A. Yasin, Abdul Rahman Said; A.K.A. Yasin, Aboud); DOB: 10 Apr 1960; POB: Bloomington, Indiana U.S.A.; SSN 156-92-9858 (U.S.A.); Passport No. 27082171 (U.S.A. (Issued 21 Jun 1992 In Amman, Jordan)); Alt. Passport No. MO887925 (Iraq); Citizen U.S.A. Abdullah Ahmed Abdullah (A.K.A. Abu Mariam; A.K.A. Al-Masri, Abu Mohamed; A.K.A. Saleh); Afghanistan; DOB: 1963; POB: Egypt; Citizen Egypt Abdullkadir, Hussein Mahamud, Florence, Italy. Abu Hafs the Mauritanian (a.k.a. Mahfouz Ould Al-Walid, Khalid Al-Shanqiti, Mafouz Walad Al-Walid, Mahamedou Ouid Slahi). DOB 1 Jan 75. Abu Zubaydah (a.k.a. Abu Zubaida, Abd Al-Hadi Al-Wahab, Zain Al-Abidin Muhahhad Husain, Zain Al-Abidin Muhahhad Husain, Zayn Al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn, Tariq). Thought to be a Saudi, Palestinian and Jordanian national. -

The Mahdi of Sudan

COMMENTARY #9 • MAY 2019 THE MAHDI OF SUDAN — PART 2 Filippo Donvito On June 29, 1881, two years after the end of the slaves’ revolt, Muhammad Ahmad, a poor Sufi from the region of Dongola in Northern Sudan, publicly announced he was the Mahdi, “the guided one”. According to several hadiths (Prophet’s sayings and deeds), the Mahdi is the great eschatological figure, the redeemer who will restore Islam to its ancient purity and start a new era of justice before the Second Coming of Jesus and the Day of Judgment. He will come from the Prophet’s family (ahl al-bayt) and bear certain markings and distinctive physical traits which ensure his identity1. Muhammad Ahmad was indeed the son of a humble boatman who traced his descent back to the Prophet Muhammad; moreover, his full name – Muhammad Ahmad ibn ‘Abd Allah – was the same as the Prophet's, another clear distinctive feature required by tradition. Foreseeing the start of a rebellion, the Egyptian government sent a small force of soldiers to arrest the Mahdi and reassert the official authority on Aba, the White Nile island where the mystic lived with 1 D. Cook, Understanding jihad, (Oakland: University of California Press, 2005), pp. 129-132; H. Laoust, Les schimes dans l’Islam (Paris: Payot, 1983), pp. 313-316. 1 COMMENTARY #9 • MAY 2019 his followers. Clearly, this measure was expected by Muhammad Ahmad, as the military were ambushed and massacred by 200 of his followers. The Mahdi was safe, but acting in such manner he had drawn all the attention to himself. -

The Notion of Mahdiyyah in the Thought of Mahdi Ibn Tumart

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 22, Issue 7, Ver. 15 (July. 2017) PP 08-13 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The Notion of Mahdiyyah in the Thought of Mahdi Ibn Tumart Dr. Abba Idris Adam and Abubakar Idris (Department of History, Faculty of Art and Education, Yobe State University, Damaturu, Nigeria). (Atiku Abubakar College of Legal and Islamic Studies, Nguru, Yobe State, Nigeria). Corresponding Author: Dr. Abba Idris Adam Abstract: The African continent has witnessed various revivalism and reform movements or (al-Islah wa al- Tajdid). These movements embarked on purifying Islam from the impurities of innovation and blind imitation. However, some of these reform movements hid under the banner of Mahdiyyah (messianism) to bring about the desired reform and re-establish Islamic state. In the case of Muhammad Ibn Abdullah (popularly known as Ibn Tumart), Mahdism was the backbone and central pillar of his movement. It is the political weapon he used to fight Moravids and overthrow their regime in North Africa. To him, Mahdism is the highest level of Imamah since Mahdi is considered to be the last Imam. This paper discusses and analyzes the notion of Mahdiyya in the thought of Muhammad Ibn Abdullah (Ibn Tumart) in his struggle to establish Almohad dynasty. It concludes by evaluating Ibn Tumart’s reform movement as one of the Islamic revolutions in Africa. The research adopts qualitative and analytical methods in discussing, analyzing and interpreting data in this paper. Keywords: Mahdiyyah, Reform, Ibn Tumart, Africa. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- Date of Submission: 12 -05-2017 Date of acceptance: 26-07-2017 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I.