Riccardo Muti Conductor Yo-Yo Ma Cello Bates the B-Sides Schumann

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SFS-Media-Mason-Bates-Grammy

Press Contacts: Public Relations National Press Representation: San Francisco Symphony Shuman Associates (415) 503-5474 (212) 315-1300 [email protected] [email protected] www.sfsymphony.org/press FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE / December 6, 2016 (High resolution images available for download from the SFS Media’s Online Press Kit) MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS AND THE SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY’S RECORDING OF MASON BATES: WORKS FOR ORCHESTRA NOMINATED FOR 2017 GRAMMY AWARD Recording on Orchestra’s in-house label SFS Media nominated for Best Orchestral Performance SAN FRANCISCO, December 6, 2016 – Music Director Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony’s live concert recording of works by Bay Area composer Mason Bates was nominated for a 2017 Grammy® Award today in the category of Best Orchestral Performance. Mason Bates: Works for Orchestra was released in March 2016 and features the first recordings of the SFS-commissioned The B-Sides and Liquid Interface, in addition to Alternative Energy. These three works illustrate Bates’s exuberantly inventive music that expands the symphonic palette with sounds of the digital age: techno, drum ‘n’ bass, field recordings and more, with the composer performing on electronica. MTT and the SFS have championed Bates’s works for over a decade, evolving a partnership built on multi-year commissioning, performing, recording, and touring projects. Click here to watch a video about Mason Bates: Works for Orchestra. "I never cease to be astonished by the San Francisco Symphony's impact on American music,” stated Mason Bates this morning. “Their performances of living legends, from Lou Harrison to John Adams, have continually thrilled and educated me. -

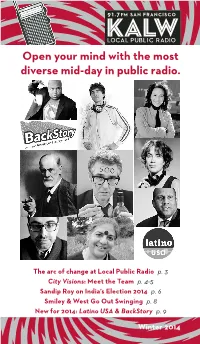

Open Your Mind with the Most Diverse Mid-Day in Public Radio

Open your mind with the most diverse mid-day in public radio. The arc of change at Local Public Radio p. 3 City Visions: Meet the Team p. 4-5 Sandip Roy on India’s Election 2014 p. 6 Smiley & West Go Out Swinging p. 8 New for 2014: Latino USA & BackStory p. 9 Winter 2014 KALW: By and for the community . COMMUNITY BROADCAST PARTNERS AIA, San Francisco • Association for Continuing Education • Berkeley Symphony Orchestra • Burton High School • East Bay Express • Global Exchange • INFORUM at The Commonwealth Club • Jewish Community Center of San Francisco • LitQuake • Mills College • New America Media • Oakland Asian Cultural Center • Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at UC Berkeley • Other Minds • outLoud Radio Radio Ambulante • San Francisco Arts Commission • San Francisco Conservatory of Music • San Quentin Prison Radio • SF Performances • Stanford Storytelling Project • StoryCorps • Youth Radio KALW VOLUNTEER PRODUCERS Rachel Altman, Wendy Baker, Sarag Bernard, Susie Britton, Sarah Cahill, Tiffany Camhi, Bob Campbell, Lisa Carmack, Lisa Denenmark, Maya de Paula Hanika, Julie Dewitt, Matt Fidler, Chuck Finney, Richard Friedman, Ninna Gaensler-Debs, Mary Goode Willis, Anne Huang, Eric Jansen, Linda Jue, Alyssa Kapnik, Carol Kocivar, Ashleyanne Krigbaum, David Latulippe, Teddy Lederer, JoAnn Mar, Martin MacClain, Daphne Matziaraki, Holly McDede, Lauren Meltzer, Charlie Mintz, Sandy Miranda, Emmanuel Nado, Marty Nemko, Erik Neumann, Edwin Okong’o, Kevin Oliver, David Onek, Joseph Pace, Liz Pfeffer, Marilyn Pittman, Mary Rees, Dana Rodriguez, -

The Audiophile Voice

Children-Adam_Graves_11-1_master_color.qxd 10/16/2019 4:26 PM Page 2 George Graves Classical Mason Bates Children of Adam Ralph Vaugh Williams Dona Nobis Pacem Richmond Symphony; Steven Smith, Cond. Michelle Areyzaga, soprano; Kevin Deas, bass-baritone Reference Recording / Fresh FR-732 IWAS BORN in Richmond, A, and In the 1970s and early ‘80s, my northward in order to visit even though my family moved to college roommate was still attend - Washington, D.C. to hear the Northern Virginia when I was three ing the university in Richmond, National Symphony Orchestra per - years old (just outside the DC working toward his eventual doctor - form or to attend one of the many “Beltway”), my relatives remained ate in psychology, so my yearly visit weekly concerts of the President’s in Richmond, and we used to visit to my parents also included a visit Army, Navy, Marine Corps or Air them often as I was growing up. to my ex-roommate. Force symphonic bands. I had heard When I graduated college and I had heard my “roomie” com - that Richmond had a civic sympho - moved to California, my father plain on the phone for a number of ny orchestra, and my friend started retired and he and my mother years about what a musical waste - to laugh when I asked him about it. moved back to Richmond. So, as an land Richmond was in those days. “They’re terrible,” was his reply. adult, when I visited my parents, it He often talked about having to “My high school band played bet - was there that I visited them. -

North Carolina Symphony Tours to Washington, D.C

North Carolina Symphony Tours to Washington, D.C. for SHIFT Festival Subject: North Carolina Symphony Tours to Washington, D.C. for SHIFT Festival From: Meredith Laing <[email protected]> Date: Wed, 15 Mar 2017 14:51:15 +0000 To: Meredith Laing <[email protected]> Dear friends, In just two weeks, the North Carolina Symphony will depart for Washington, D.C., to par>cipate in the inaugural year of SHIFT: A Fes+val of American Orchestras. NCS is one of just four U.S. orchestras selected for this na>onal fes>val! We will bring music with direct connec>ons to North Carolina to our na>on’s capital, and the programs will be previewed in Raleigh. Details about the SHIFT fes>val and the preview concerts are below and aFached. Thank you for your support of the North Carolina Symphony as we embark on this adventure with the privilege of represen>ng our state! All the best, Meredith -- Meredith Kimball Laing Director of Communications North Carolina Symphony 3700 Glenwood Avenue, Suite 130 Raleigh, NC 27612 919.789.5484 www.ncsymphony.org Experience the Power of Live Music Join Us for Upcoming Concerts Learn How We Serve North Carolina Read Our Report to the Community Support Your Symphony Make a Donation FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Meredith Kimball Laing 919.789.5484 [email protected] North Carolina Symphony Tours to Washington, D.C. as One of Four Orchestras Chosen for SHIFT: A Festival of American Orchestras 1 of 5 4/20/17, 4:08 PM North Carolina Symphony Tours to Washington, D.C. -

An Analysis of Honegger's Cello Concerto

AN ANALYSIS OF HONEGGER’S CELLO CONCERTO (1929): A RETURN TO SIMPLICITY? Denika Lam Kleinmann, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: Eugene Osadchy, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor David Schwarz, Committee Member Daniel Arthurs, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kleinmann, Denika Lam. An Analysis of Honegger’s Cello Concerto (1929): A Return to Simplicity? Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2014, 58 pp., 3 tables, 28 examples, 33 references, 15 titles. Literature available on Honegger’s Cello Concerto suggests this concerto is often considered as a composition that resonates with Les Six traditions. While reflecting currents of Les Six, the Cello Concerto also features departures from Erik Satie’s and Jean Cocteau’s ideal for French composers to return to simplicity. Both characteristics of and departures from Les Six examined in this concerto include metric organization, thematic and rhythmic development, melodic wedge shapes, contrapuntal techniques, simplicity in orchestration, diatonicism, the use of humor, jazz influences, and other unique performance techniques. Copyright 2014 by Denika Lam Kleinmann ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..iv LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES………………………………………………………………..v CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION………..………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER II: HONEGGER’S -

An Examination of Stylistic Elements in Richard Strauss's Wind Chamber Music Works and Selected Tone Poems Galit Kaunitz

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 An Examination of Stylistic Elements in Richard Strauss's Wind Chamber Music Works and Selected Tone Poems Galit Kaunitz Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC AN EXAMINATION OF STYLISTIC ELEMENTS IN RICHARD STRAUSS’S WIND CHAMBER MUSIC WORKS AND SELECTED TONE POEMS By GALIT KAUNITZ A treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Galit Kaunitz defended this treatise on March 12, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Eric Ohlsson Professor Directing Treatise Richard Clary University Representative Jeffrey Keesecker Committee Member Deborah Bish Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii This treatise is dedicated to my parents, who have given me unlimited love and support. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee members for their patience and guidance throughout this process, and Eric Ohlsson for being my mentor and teacher for the past three years. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ vi Abstract -

Briefe Aus Italien

*«> THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES EX LIBRIS GUSTAV GLÜCK Ubi o CARL JUSTI BRIEFE AUS ITALIEN 1922 VERLAG VON FRIEDRICH COHEN • BONN Carl Jusii 1868 CARL JUSTI BRIEFE AUS ITALIEN 1922 VERLAG VON FRIEDRICH COHEN • BONN Copyright 1922 by Friedrich Cohen, Bonn Art Library VORWORT WENN Carl Justi es unternommen hat, in Briefen an die Seinen Eindrücke bei seiner ersten Fahrt nach Italien, das er schon so lange sehnsüchtig mit der Seele gesucht hatte, zu schildern, so wird man erwarten können, daß die Fähigkeit, die ihn zum ersten Kunstkenner unserer Zeit gemacht hat, auch hier sich zeigen werde, die Fähigkeit, überall das Characteristische zu sehen und das Schöne zu empfinden. Und denkt man weiter an den Meister des Worts, als welcher er sich in seinen Büchern ge- zeigt hat, an die unglaubliche Vielseitigkeit seiner Kenntnisse in Geschichte und Literatur, so wird man nicht zweifeln, daß seine Berichte aus Italien durch ganz besondere Reize ausgezeichnet sein werden. Daher wurde mir dieErlaubniß der Schwester des großen Meisters, diese Briefe zu lesen, welche er von der Reise an Eltern vmd Ge- schwister gerichtet hat, zu einem werthvollen Geschenk. Und ich fand meine Erwartungen ganz erfüllt. Justi giebt nicht einen eigent- lichen Reisebericht, sondern er greift einzelne Scenen aus dem Er- lebten und Geschauten heraus; mag er über Kirnst sprechen, oder über Kirchen- und Volksfeste, Naturschildervmgen geben oder Menschen zeichnen, immer sind es in sich vollendete Skizzen, feine Vergleiche, geistvolle Bemerkungen, die oft einem selbst nur dunkel bewußt gewordene Empfindungen klar aussprechen. Die Leetüre wurde mir ein hoher Genuß, und da meinte ich, daß es vielen ebenso gehen werde, wie mir. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

3126.Pdf (218.6Kb)

J credits on his own, but working together, as they have for five years, they University of Washington Stfl defmitely exceed the sum of their very excellent individual pans. TIlE SCHOOL OF MUSIC . New Stories can define fue and funkiness, but they are just as persuasive and { 9fy riveting in impressionistic explorations. New Stories grooves bard and interacts presents effortlessly. They perfonn memorable original compositions and their highly (()~II imaginative ammgements of standards with the same virtuosity and creative flex ibility. New Stories' soon-to-be-released flfSt recording captures the musicality, . invention and drive that have been winning them rave reviews and festival invita tions and reinvitadons since the group's inception. MARC SEALES 1994-95 UPCOMING EVENTS piano and synthesizer October 13, William Bergsma Memorial Concert 8 PM, Meany Theater. October 16, Christopher O'Riley, piano master class (in collaboration with the Seattle Symphony.) 6 PM, Brechemin Auditorium. • October 17, Yosbiyuki Ishikawa, bassoon master class, 3:30 PM, Brecbemin Auditorium. In a October 17, Yosbiyuki Ishikawa, bassoon, and Laurent Philippe piano, 8 PM, Brechemin Auditorium. October 18, Faculty Recital: Music for Oboe Voice and Piano, with Alex Klein, Carmen Pelton and Cmig Sheppard. 8 PM, Meany Theater. Faculty Artist Recital October 23, Faculty Recital: Carole Terry, organ. 4 PM, St Mark's CatbedrnI. October 24, Voice Division Recital. 7 PM. Brecbemin Auditorium. October 28, Littlefaeld Organ Halloween Concert 12:30 PM and 8 PM, Walker Ames Room, Kane Hall. November 4, Jazz Artists Series. 8 PM, Brecbemin Auditorium. assisted by November 6, Faculty Recital: Soni Ventorum Wind Quintet, 3 PM, Brecbemin Auditorium. -

Eine Alpensinfonie and Symphonia Domestica in Full Score Pdf, Epub, Ebook

EINE ALPENSINFONIE AND SYMPHONIA DOMESTICA IN FULL SCORE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Richard Strauss | 288 pages | 22 Oct 2009 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486277257 | English | New York, United States Eine Alpensinfonie and Symphonia Domestica in Full Score PDF Book Oehms Classics. Schonberg put it, Strauss would say things that would have meant being sent to a concentration camp had he not been the icon he was and the Nazi's simply "did not know exactly what to do with him. Seller Inventory M13J Subscribe to our Weekly Newsletter Want to know first what the latest reviews are that have been posted to ClassicsToday each week? As this print on demand book is reprinted from a very old book, there could be some missing or flawed pages, but we always try to make the book as complete as possible. Carlton Classics. Once started, however, he gave it his main attention for almost 40 years, producing 15 operas in that period. Salome, with its shocking, perverse sensuality, and Elektra, which goes beyond that in violence and unremitting tension, are prime examples of German expressionism in its most lurid phase. Paul Lewis , Piano. Munich: F. It was also the first opera in which Strauss collaborated with the poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal. IMP Classics Franz Konwitschny. Rosenkavalier opera Rosenkavalier , Op. In principle, however, Strauss's method remained constant. Preiser Records. Orfeo C B. Classica d'Oro There are only six works in his entire output dating from after which are for chamber ensembles, and four are arrangements of portions of his operas. AllMusic Featured Composition Noteworthy. -

Mason Bates Mothership (2011)

MASON BATES MOTHERSHIP (2011) “The joining of horse hair and electrons seems Having raced across the world, the ship slows “The orchestra is seamless, completely complimentary - totally additive down. Electronic beeps provide a docking of the resources of the ensemble” TommyTrumpets signal, inviting a pair of soloists to come aboard the world’s greatest “Always enjoy rocking out to this piece!! Full of the mothership. A door opens with a hydraulic emotion. :-)” Jay Coles hiss and the first visitor’s musical voice takes synthesiser” Mason Bates “That Bassoon part is so badass! What a very cool over, quickly followed by another. True to the piece. Unique, and I like the electronic drums! It really Internet’s democracy, soloists are welcome to adds character.” ian2120 improvise on any instrument to make their own unique contribution. The pattern repeats, with These are just a handful of the 500+ comments the ship racing off to a new location, but the left on YouTube videos of Mothership. The second ‘docking episode’ welcomes visitors Internet has brought a new freedom of with very different personalities. Music and expression, allowing us to connect with other Internet both encompass hugely varied voices. people like never before – across continents, between age groups, and blind of education. As sci-fi as this seems, Mothership actually ‘TommyTrumpets’ could just as easily be your takes its structure from two centuries earlier. next door neighbour as Thomas Adès or Tom In his Second Symphony, Robert Schumann Hiddleston, the Internet having brought about wrote a scherzo with double trio, a form that an utterly democratic forum to consume and Bates takes and updates. -

Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104 ANTONÍN DVORÁK

I believe Prokofiev is the most imaginative orchestrator of all time. He uses the percussion and the special effects of the strings in new and different ways; always tasteful, never too much of any one thing. His Symphony No. 5 is one of the best illustrations of all of that. JANET HALL, NCS VIOLIN Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104 ANTONÍN DVORÁK BORN September 8, 1841, near Prague; died May 1, 1904, in Prague PREMIERE Composed 1894-1895; first performance March 19, 1896, in London, conducted by the composer with Leo Stern as soloist OVERVIEW During the three years that Dvořák was teaching at the National Conservatory of Music in New York City, he was subject to the same emotions as most other travelers away from home for a long time: invigoration and homesickness. America served to stir his creative energies, and during his stay, from 1892 to 1895, he composed some of his greatest scores: the “New World” Symphony, the Op. 96 Quartet (“American”), and the Cello Concerto. He was keenly aware of the new musical experiences to be discovered in the land far from his beloved Bohemia when he wrote, “The musician must prick up his ears for music. When he walks he should listen to every whistling boy, every street singer or organ grinder. I myself am often so fascinated by these people that I can scarcely tear myself away.” But he missed his home and, while he was composing the Cello Concerto, looked eagerly forward to returning. He opened his heart in a letter to a friend in Prague: “Now I am finishing the finale of the Cello Concerto.