BMJ Open Is Committed to Open Peer Review. As Part of This Commitment We Make the Peer Review History of Every Article We Publish Publicly Available

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hebi Sani: Mental Well Being Among the Working Class Afro-Surinamese in Paramaribo, Suriname

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2007 HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE IN PARAMARIBO, SURINAME Aminata Cairo University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cairo, Aminata, "HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE IN PARAMARIBO, SURINAME" (2007). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 490. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/490 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Aminata Cairo The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2007 HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE IN PARAMARIBO, SURINAME ____________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION ____________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Aminata Cairo Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Deborah L. Crooks, Professor of Anthropology Lexington, Kentucky 2007 Copyright © Aminata Cairo 2007 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION HEBI SANI: MENTAL WELL BEING AMONG THE WORKING CLASS AFRO-SURINAMESE -

Proefschrift-Witteveen.Pdf

505381-os-Witteveen.indd 1 05-10-16 16:51 505381-L-os-Witteveen Processed on: 5-10-2016 SAFE MOTHERHOOD Severe acute maternal morbidity: risk factors in the Netherlands and validation of the WHO Maternal Near Miss tool Tom Witteveen 505381-L-bw-Witteveen Processed on: 6-10-2016 Cover design: Tom Witteveen Design and layout: Legatron Electronic Publishing, Rotterdam Printing: Ipskamp Printing, Enschede ISBN: 978-90-9029916-7 ©2016 Tom Witteveen, Leiden, the Netherlands. Financial support for the publication of this thesis was kindly provided by: Stichting HELLP Syndroom; Department of Obstetrics, Leiden University Medical Center. All rights reserved. No parts of this thesis may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission of the author. The copyright of articles that have been published or accepted has been transferred to the publishers of the corresponding journals. 505381-L-bw-Witteveen Processed on: 6-10-2016 SAFE MOTHERHOOD Severe acute maternal morbidity: risk factors in the Netherlands and validation of the WHO Maternal Near Miss tool PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van Rector Magnificus prof.mr. C.J.J.M. Stolker, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op 2 november 2016 klokke 11:15 uur DOOR Tom Witteveen geboren te Emmen in 1987 505381-L-bw-Witteveen Processed on: 6-10-2016 Promotores: prof. dr. J. van Roosmalen prof. dr. K.W.M. Bloemenkamp Co-promotores: dr. T. van den Akker dr. J.J. Zwart (Deventer Ziekenhuis) Overige leden: prof. -

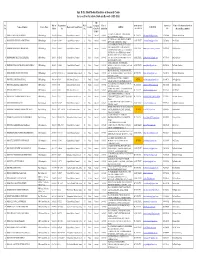

PG RECORD 2015-16.Xlsx

Smt. B. K. Shah Medical Institute & Research Centre 1st year Post Graduate Students Record - 2015-2016 Sub Sr. Date of Registration Merit Category Date of SAME STATE / CONTACT Name of Teachers under whom Name of Student Course Name Registered Council Name Gender ADRESS E-MAIL ID No. Birth No. No. (Gen/SC/S Admission OUT STATE NO. the candidate admitted T/OBC) 10, SAHAJANAND SOC., URBAN BANK 1 DR.PATEL NISHANT BABUBHAI MD Radiology 28-12-90 G-52885 Gujarat Medical Council 1 Male General 16-04-15 OUT STATE [email protected] 9712435084 Dr.Parthiv Brahmbhatt ROAD, MEHSANA-384002 57, TARNG SOC., OPP. AKOTA STADIUM, 2 DR.PARIKH CHINMAY SANDIPKUMAR MD Radiology 27-12-90 G-51016 Gujarat Medical Council 2 Male General 16-04-15 SAME STATE [email protected] 9725702062 Dr.S.B.Patel BPC ROAD, VADODARA-390020 10, CHANDRA RATNA FLAT, GUJARAT COLLEGE ROAD,NR. LADIES HOSTEL, 3 DR.MODI JAIMIN RAJENDRAKUMAR MD Radiology 13-12-88 G-50513 Gujarat Medical Council 3 Male General 16-04-15 SAME STATE [email protected] 9924132102 Dr.Pallavi Shah VAGHBAKRI DEPONI GALI, ELISBRIDGE, PRITAM NAGAR, AHEMDABAD-380006 MANJUL', STREET NO-2, CHOTUNAGAR 4 DR.DOMADIA NIKET KAMLESHBHAI MD Radiology 12-01-91 G-52402 Gujarat Medical Council 4 Male General 16-04-15 SOC., B/H. HANUMAN MANDIR, RAIYA SAME STATE [email protected] 9879074080 Dr.Pradip Jhala ROAD, RAJKOT-360007 PATEL PARK, B/H. JIVAN DHARA 5 DR.DHOLU MANOJKUMAR GHANSHYAMBHAI MD Radiology 18-06-91 G-52564 Gujarat Medical Council 5 Male General 16-04-15 HOSPITAL, OPP. -

Fiscal Space for Health in Suriname Final Report

Fiscal Space for Health in Suriname Final Report A. Lorena Prieto, PhD Senior Economist Washington DC. December, 2018 FISCAL SPACE FOR HEALTH SURINAME FINAL REPORT − Contents I. General background ........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Objectives ................................................................................................................... 4 1.1.1 General objective ................................................................................................. 4 1.1.2 Specific objectives ................................................................................................ 4 1.2 Structure .................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. II. General context ................................................................................................................ 4 2.1 Population and social context ..................................................................................... 4 2.2 Macroeconomic overview........................................................................................... 6 2.3 Health status context ................................................................................................. 16 2.4 Health sector overview ............................................................................................. 22 2.4.1 System Resources ............................................................................................... 24 2.4.2 Financing -

Sabajo Baseline – Health Status

Baseline Health Status Suriname Managing Partner, Suriname Gold Project CV November 2017 Managing Partner, Suriname Gold Project CV Baseline Health Status: Suriname, November 2017 Disclaimer This report is written as a general guide only and the information stated therein is provided on an “as is” and “as available” basis. International SOS (hereinafter referred to as “Intl.SOS”) will take reasonable care in preparing this report. However, Intl.SOS, its holding, subsidiary, group companies, affiliates, third-party content providers or licensors and each of their respective officers, directors, employees, representatives, licensees and agents hereinafter collectively referred to as the “Intl.SOS Parties”) do not make any representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, authenticity, reliability, or suitability with respect to this report. Intl.SOS hereby disclaims and Suriname Gold Project CV hereby waives on its behalf and on behalf of its holding, subsidiary, group companies, affiliates and each of their respective officers, directors, employees, representatives and agents its and their respective rights to claim against any or all of the Intl.SOS Parties for any or all liability including, without limiting the generality of the foregoing, any loss or damage to property; bodily injury or death; loss or anticipated loss of profit, loss or anticipated loss of revenue, economic loss or loss of data, whether or not flowing directly or indirectly from the information, act or omission in question; business interruption, loss of use of equipment, loss of contract or loss of business opportunity; or indirect, special, incidental, consequential, exemplary, contingent, penal or punitive damages, howsoever arising, including out of negligence or willful default or out of the information contained in or omitted from the report or other information which is referenced by, or linked to this report. -

Conferring of Degrees

ONE HUNDRED AND TWELFTH YEAR two thousand and eighteen Conferring of Degrees MAY 27 AND JUNE 10 LOMA LINDA, CALIFORNIA Message from the President Congratulations to the Class of 2018. One of the greatest joys experienced by our campus community is the opportunity to celebrate your academic excellence and personal achievements. This 112th commencement season marks the culmination of your study and professional preparation, which has equipped you to meet the next great adventures of your lives. You and those who have supported you are to be commended. Now and for all time, you occupy a place among the alumni of this historic institution. I urge you always to model in your personal and professional life the excellence and vision, the courage and resilience, the passion and compassion that continue to shape and enhance our global reputation and legacy. As you move beyond this weekend to the world of work or the pursuit of advanced degrees, I know that your commitment to our mission and values will be evident as your knowledge and skills are used to “continue the teaching and healing ministry of Jesus Christ—to make man whole.” Now go with confidence wherever your dreams may lead you—questioning, learning, and challenging as you change our world for the better. I wish for you a satisfying and successful journey as you serve in the name and spirit of our gracious God. Richard H. Hart, M.D., Dr.P.H. 1 Contents Message from the President 1 2018 Events of Commencement 3 The Academic Procession 5 Significance of Academic Regalia 7 The Good Samaritan -

Suriname Progress Report on the Implementation of the Montevideo Consensus 2013-2018

Suriname Progress report on the implementation of the Montevideo Consensus 2013-2018 Compiled by Ministry of Home Affairs Yvonne Towikromo Michele Jules Chitra Mohanlal Marvin Towikromo Julia Terborg (Consultant) Paramaribo, March 2018 Table of Contents Preface 3 Abbreviations 4 Part one: National Coordination Mechanism and Process 6 Part two: General description of the country 7 Part three: Implementation of the Montevideo Consensus 11 Chapter A: Full integration of population dynamics into sustainable development 11 Chapter B: Rights, needs, responsibilities and requirements of girls, boys, Adolescents and youth 20 Chapter C: Ageing, social protection and socioeconomic challenge 27 Chapter D: Universal access to sexual and reproductive health services 33 Chapter E. Gender Equality 44 Chapter F: International migration and protection of the human rights of all migrants 52 Chapter H: Indigenous peoples: interculturalism and rights 57 Conclusions 61 Statistical Annex 62 2 3 ABBREVIATIONS A.O.V General Old-age provision ADeKUS Anton De Kom University of Suriname AIDS Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome AVRR Assisted Voluntary Return and reintegration BEIP Basic Education Improvement Project Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, punishment and eradication of violence Belem do Para against women BGA Bureau Gender Affairs BOS Bureau for Educational Information and Study Facilities BPfa Beijing Platform for action BUPO International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights CARICOM Caribbean Community and Common Market CBB Central Bureau -

Socio-Economic Impact Assessment and Response Plan for Covid-19 in Suriname

SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACT ASSESSMENT AND RESPONSE PLAN FOR COVID-19 IN SURINAME TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 PREFACE . 6 8.1.1 STRENGTHENING THE HEALTH SYSTEM’S CAPACITY TO RESPOND TO COVID-19 . 60 2 INTRODUCTION . 8 8.1.2 STRENGTHENING CAPACITY TO MAINTAIN ESSENTIAL HEALTH SERVICES DURING COVID-19 . 62 3 COMMODITY DEPENDENCE, 8.1.3 AN OPPORTUNITY TO BUILD BACK BETTER . 65 COMMODITY SHOCK AND VULNERABILITY . 11 8.2 PILLAR 2: PROTECTING PEOPLE 3.1 COMMODITY DEPENDENCE AND – SOCIAL PROTECTION AND BASIC SERVICES . 71 THE ECONOMY . 12 8.2.1 DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AND 3.2 VULNERABILITY AND REDUCED RESILIENCE: UNEQUAL DISTRIBUTION OF HOUSEHOLDS AND FIRMS . 17 HOUSEHOLD BURDEN . 73 8.2.2 IMPACT ON EDUCATION . 71 4 MOST-AT-RISK GROUPS . 22 8.2.3 IMPACT ON WATER SANITATION AND HYGIENE . 73 5 PREPAREDNESS . 28 8.2.4 SOCIAL PROTECTION . 77 5.1 PREPAREDNESS: HEALTH SYSTEM . 28 8.3 PILLAR 3: ECONOMIC RESPONSE AND RECOVERY 5.2 PREPAREDNESS: SOCIAL SAFETY NET . 32 - PROTECTING JOBS, SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED ENTERPRISES AND THE MOST VULNERABLE 5.3 PREPAREDNESS: ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE . 33 PRODUCTIVE ACTORS . 79 8.3.1 SUPPORTING INFORMAL SECTORS . 80 6 COVID-19 AND POLICY RESPONSE . 35 8.3.2 PRODUCTION OF FOOD . 81 6.1 POLICY BUFFERS . 38 8.4 PILLAR 4: MACROECONOMIC RESPONSE . 82 6.2 MEASURES TAKEN . 39 8.5 PILLAR 5: SOCIAL COHESION 6.3 COMMUNICATION AND COMPLIANCE ISSUES . 42 AND COMMUNITY RESILIENCE . 83 8.5.1 SOCIAL COHESION . 83 7 SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACT . 48 8.5.2 PROTECTION OF COMMUNITIES . 84 7. 1 INCOME LOSS . -

RESTRICTED WT/TPR/S/282 22 April 2013

RESTRICTED WT/TPR/S/282 22 April 2013 (13-2056) Page: 1/78 Trade Policy Review Body TRADE POLICY REVIEW REPORT BY THE SECRETARIAT SURINAME This report, prepared for the second Trade Policy Review of Suriname, has been drawn up by the WTO Secretariat on its own responsibility. The Secretariat has, as required by the Agreement establishing the Trade Policy Review Mechanism (Annex 3 of the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization), sought clarification from Suriname on its trade policies and practices. Any technical questions arising from this report may be addressed to Messrs John Finn (tel: 022/739 5081), Michael Kolie (tel: 022/739 5931), and Bernard Kuiten (tel: 022/739 5676). Document WT/TPR/G/282 contains the policy statement submitted by Suriname. Note: This report is subject to restricted circulation and press embargo until the end of the first session of the meeting of the Trade Policy Review Body on Suriname. This report was drafted in English. WT/TPR/S/282 • Suriname - 2 - CONTENTS SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ 6 1 ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT .......................................................................................... 8 1.1 Overview .................................................................................................................. 8 1.2 Recent Economic Developments.................................................................................. 10 1.3 Developments in Trade ............................................................................................. -

Malaria in Suriname: a New Era

MALARIA IN SURINAME: A NEW ERA IMPACT OF MODIFIED INTERVENTION STRATEGIES ON ANOPHELES DARLINGI POPULATIONS AND MALARIA INCIDENCE HÉLÈNE HIWAT - VAN LAAR Malaria in Suriname: a New Era Impact of modified intervention strategies on Anopheles darlingi populations and malaria incidence HÉLÈNE HIWAT – VAN LAAR ThESIS COMMITTEE ThESIS SUPERVISORS Prof. Dr. Ir. W. Takken Personal Chair at the Laboratory of Entomology Wageningen University Prof. Dr. M. Dicke Professor of Entomology Wageningen University OTHER MEMBERS Prof. Dr. Ir. H.F.J. Savelkoul Wageningen University Prof. Dr. R.W. Sauerwein Radboud University Nijmegen Prof. Dr. Ir. C. Leeuwis Wageningen University Dr.Ir. E.-J. Scholte New Food and Consumer Product- Safety Authority, Wageningen This research was conducted under the auspices of the C.T. de Wit Graduate School for Production Ecology and Resource Conservation. Malaria in Suriname: a New Era Impact of modified intervention strategies on Anopheles darlingi populations and malaria incidence HÉLÈNE HIWAT – VAN LAAR ThESIS Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. Dr. M.J. Kropff, in the presence of the Thesis committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public On Monday 21 November 2011 At 4 p.m. in the Aula Hiwat – Van Laar, H MALARIA IN SURINAME: A NEW ERA. - Impact of modified intervention strategies on Anopheles darlingi populations and malaria incidence. PhD Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2011) With references, with summary in Dutch ISBN 978-94-6173-037-4 ABSTRACT Malaria is an infectious disease caused by Plasmodium blood parasites 5 | which live inside the human host and are spread by Anopheles mosquitoes. -

Suriname Minamata Initial Assessment

REPUBLIC OF SURINAME SURINAME MINAMATA INITIAL ASSESSMENT REPORT 2020 Foreword This Report was made under the GEF Enabling Activity: Suriname acceded to the Minamata Convention on 02 August 2018. In its process towards acces- “Minamata Initial Assessment for Suriname” (project number 00095987). sion, the Government of Suriname started in 2013 with the legal and institutional analysis of the then current situation towards the use of mercury and the role of the various actors. This analysis resulted in the publication of an Advice Document and a Roadmap in 2015 which stated the activities that had to be implemented to phase out the use of mercury in Suriname. Since the outcome of the Advice Document, the government started the process to ratify the Minamata Convention and also started to implement the roadmap. For Suriname one of the important obligations under this Convention is to formulate a National Action Plan (NAP) for the Artisanal and Small Scale Gold Mining (ASGM). Traditionally Artisanal and Small Scale Gold Mining has always been a source of income for parts of the community. The negative impact of mercury on health and environment in Suriname cannot be overlooked and needs to be addressed. Suriname applied for funding from the Global Environment Facility for assisting the country in preparing the national processes of meeting the obligations of the Minamata Convention on Mercury. Through the enabling activities of the GEF, Suriname has been able to implement the project: GEF 00095987 “Minamata Initial Assessment Report” (MIA report). Through this project, which started in October 2017, Suriname has been able to further its na- tional agenda on the phasing out of the use of mercury. -

Lingua, Traduzione, Didattica Collana Fondata Da Anna Cardinaletti, Fabrizio Frasnedi, Giuliana Garzone

Lingua, traduzione, didattica Collana fondata da Anna Cardinaletti, Fabrizio Frasnedi, Giuliana Garzone Direzione Anna Cardinaletti, Giuliana Garzone, Laura Salmon Comitato scientifico Paolo Balboni, Università Ca’ Foscari di Venezia Maria Vittoria Calvi, Università degli Studi di Milano Guglielmo Cinque, Università Ca’ Foscari di Venezia Michele Cortelazzo, Università degli Studi di Padova Maurizio Gotti, Università degli Studi di Bergamo Alessandra Lavagnino, Università degli Studi di Milano Leo Schena, Università degli Studi di Modena Marcello Soffritti, Università degli Studi di Bologna, sede di Forlì La collana intende accogliere contributi dedicati alla descrizione e all’analisi dell’italiano e di altre lingue moderne e antiche, secondo l’ampio ventaglio delle teorie linguistiche e con riferimento alle realizzazioni scritte e orali, offrendo così strumenti di lavoro sia agli specialisti del settore sia agli studenti. Nel quadro dello studio teorico dei meccanismi che governano il funzionamento e l’evoluzione delle lingue, la collana riserva ampio spazio ai contributi dedicati all’analisi del testo tradotto, in quanto luogo di contatto e veicolo privilegiato di interferenza. Parallelamente, essa è aperta ad accogliere lavori sui temi relativi alla didattica dell’italiano e delle lingue straniere, nonché alla didattica della traduzione, riportando così i risultati delle indagini descrittive e teoriche a una dimensione di tipo formativo. La vocazione della collana a coniugare la ricerca teorica e la didattica, inoltre, è solo il versante