Redalyc.Lexicographic Studies in Medicine: Academic Word List For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proefschrift-Witteveen.Pdf

505381-os-Witteveen.indd 1 05-10-16 16:51 505381-L-os-Witteveen Processed on: 5-10-2016 SAFE MOTHERHOOD Severe acute maternal morbidity: risk factors in the Netherlands and validation of the WHO Maternal Near Miss tool Tom Witteveen 505381-L-bw-Witteveen Processed on: 6-10-2016 Cover design: Tom Witteveen Design and layout: Legatron Electronic Publishing, Rotterdam Printing: Ipskamp Printing, Enschede ISBN: 978-90-9029916-7 ©2016 Tom Witteveen, Leiden, the Netherlands. Financial support for the publication of this thesis was kindly provided by: Stichting HELLP Syndroom; Department of Obstetrics, Leiden University Medical Center. All rights reserved. No parts of this thesis may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission of the author. The copyright of articles that have been published or accepted has been transferred to the publishers of the corresponding journals. 505381-L-bw-Witteveen Processed on: 6-10-2016 SAFE MOTHERHOOD Severe acute maternal morbidity: risk factors in the Netherlands and validation of the WHO Maternal Near Miss tool PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van Rector Magnificus prof.mr. C.J.J.M. Stolker, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op 2 november 2016 klokke 11:15 uur DOOR Tom Witteveen geboren te Emmen in 1987 505381-L-bw-Witteveen Processed on: 6-10-2016 Promotores: prof. dr. J. van Roosmalen prof. dr. K.W.M. Bloemenkamp Co-promotores: dr. T. van den Akker dr. J.J. Zwart (Deventer Ziekenhuis) Overige leden: prof. -

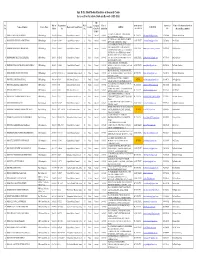

PG RECORD 2015-16.Xlsx

Smt. B. K. Shah Medical Institute & Research Centre 1st year Post Graduate Students Record - 2015-2016 Sub Sr. Date of Registration Merit Category Date of SAME STATE / CONTACT Name of Teachers under whom Name of Student Course Name Registered Council Name Gender ADRESS E-MAIL ID No. Birth No. No. (Gen/SC/S Admission OUT STATE NO. the candidate admitted T/OBC) 10, SAHAJANAND SOC., URBAN BANK 1 DR.PATEL NISHANT BABUBHAI MD Radiology 28-12-90 G-52885 Gujarat Medical Council 1 Male General 16-04-15 OUT STATE [email protected] 9712435084 Dr.Parthiv Brahmbhatt ROAD, MEHSANA-384002 57, TARNG SOC., OPP. AKOTA STADIUM, 2 DR.PARIKH CHINMAY SANDIPKUMAR MD Radiology 27-12-90 G-51016 Gujarat Medical Council 2 Male General 16-04-15 SAME STATE [email protected] 9725702062 Dr.S.B.Patel BPC ROAD, VADODARA-390020 10, CHANDRA RATNA FLAT, GUJARAT COLLEGE ROAD,NR. LADIES HOSTEL, 3 DR.MODI JAIMIN RAJENDRAKUMAR MD Radiology 13-12-88 G-50513 Gujarat Medical Council 3 Male General 16-04-15 SAME STATE [email protected] 9924132102 Dr.Pallavi Shah VAGHBAKRI DEPONI GALI, ELISBRIDGE, PRITAM NAGAR, AHEMDABAD-380006 MANJUL', STREET NO-2, CHOTUNAGAR 4 DR.DOMADIA NIKET KAMLESHBHAI MD Radiology 12-01-91 G-52402 Gujarat Medical Council 4 Male General 16-04-15 SOC., B/H. HANUMAN MANDIR, RAIYA SAME STATE [email protected] 9879074080 Dr.Pradip Jhala ROAD, RAJKOT-360007 PATEL PARK, B/H. JIVAN DHARA 5 DR.DHOLU MANOJKUMAR GHANSHYAMBHAI MD Radiology 18-06-91 G-52564 Gujarat Medical Council 5 Male General 16-04-15 HOSPITAL, OPP. -

BMJ Open Is Committed to Open Peer Review. As Part of This Commitment We Make the Peer Review History of Every Article We Publish Publicly Available

BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034702 on 13 September 2020. Downloaded from BMJ Open is committed to open peer review. As part of this commitment we make the peer review history of every article we publish publicly available. When an article is published we post the peer reviewers’ comments and the authors’ responses online. We also post the versions of the paper that were used during peer review. These are the versions that the peer review comments apply to. The versions of the paper that follow are the versions that were submitted during the peer review process. They are not the versions of record or the final published versions. They should not be cited or distributed as the published version of this manuscript. BMJ Open is an open access journal and the full, final, typeset and author-corrected version of record of the manuscript is available on our site with no access controls, subscription charges or pay-per-view fees (http://bmjopen.bmj.com). If you have any questions on BMJ Open’s open peer review process please email [email protected] http://bmjopen.bmj.com/ on September 25, 2021 by guest. Protected copyright. BMJ Open BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034702 on 13 September 2020. Downloaded from Cohort profile: The Caribbean Consortium for Research in Environmental and Occupational Health (CCREOH) MeKiTamara Cohort Study: Influences of complex environmental exposures on maternal and child health in For peer Surinamereview only Journal: BMJ Open Manuscript ID bmjopen-2019-034702 Article Type: -

Conferring of Degrees

ONE HUNDRED AND TWELFTH YEAR two thousand and eighteen Conferring of Degrees MAY 27 AND JUNE 10 LOMA LINDA, CALIFORNIA Message from the President Congratulations to the Class of 2018. One of the greatest joys experienced by our campus community is the opportunity to celebrate your academic excellence and personal achievements. This 112th commencement season marks the culmination of your study and professional preparation, which has equipped you to meet the next great adventures of your lives. You and those who have supported you are to be commended. Now and for all time, you occupy a place among the alumni of this historic institution. I urge you always to model in your personal and professional life the excellence and vision, the courage and resilience, the passion and compassion that continue to shape and enhance our global reputation and legacy. As you move beyond this weekend to the world of work or the pursuit of advanced degrees, I know that your commitment to our mission and values will be evident as your knowledge and skills are used to “continue the teaching and healing ministry of Jesus Christ—to make man whole.” Now go with confidence wherever your dreams may lead you—questioning, learning, and challenging as you change our world for the better. I wish for you a satisfying and successful journey as you serve in the name and spirit of our gracious God. Richard H. Hart, M.D., Dr.P.H. 1 Contents Message from the President 1 2018 Events of Commencement 3 The Academic Procession 5 Significance of Academic Regalia 7 The Good Samaritan -

Lingua, Traduzione, Didattica Collana Fondata Da Anna Cardinaletti, Fabrizio Frasnedi, Giuliana Garzone

Lingua, traduzione, didattica Collana fondata da Anna Cardinaletti, Fabrizio Frasnedi, Giuliana Garzone Direzione Anna Cardinaletti, Giuliana Garzone, Laura Salmon Comitato scientifico Paolo Balboni, Università Ca’ Foscari di Venezia Maria Vittoria Calvi, Università degli Studi di Milano Guglielmo Cinque, Università Ca’ Foscari di Venezia Michele Cortelazzo, Università degli Studi di Padova Maurizio Gotti, Università degli Studi di Bergamo Alessandra Lavagnino, Università degli Studi di Milano Leo Schena, Università degli Studi di Modena Marcello Soffritti, Università degli Studi di Bologna, sede di Forlì La collana intende accogliere contributi dedicati alla descrizione e all’analisi dell’italiano e di altre lingue moderne e antiche, secondo l’ampio ventaglio delle teorie linguistiche e con riferimento alle realizzazioni scritte e orali, offrendo così strumenti di lavoro sia agli specialisti del settore sia agli studenti. Nel quadro dello studio teorico dei meccanismi che governano il funzionamento e l’evoluzione delle lingue, la collana riserva ampio spazio ai contributi dedicati all’analisi del testo tradotto, in quanto luogo di contatto e veicolo privilegiato di interferenza. Parallelamente, essa è aperta ad accogliere lavori sui temi relativi alla didattica dell’italiano e delle lingue straniere, nonché alla didattica della traduzione, riportando così i risultati delle indagini descrittive e teoriche a una dimensione di tipo formativo. La vocazione della collana a coniugare la ricerca teorica e la didattica, inoltre, è solo il versante -

Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice

Supplement to January/February 2016 Volume 39, Number 1S ISSN 1533-1458 www.journalofi nfusionnursing.com Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice Funded by an educational grant from BD Medical NANv39n1S-Cover.indd 1 31/12/15 4:27 PM 31/12/15 4:27 PM Volume 39, Number 1S Supplement to Journal of Infusion Nursing January/February 2016 NANv39n1S-Cover.indd 2 Seamless Patient Care, with an IV Catheter that Lasts BD Nexiva™ Closed IV Catheter System Longer dwell times can reduce painful restarts. Let’s admit it. Few people look forward to having an IV catheter placed. Patients don’t like it. Clinicians don’t enjoy it. And all that is compounded when a catheter fails or has to be replaced. Use of the BD Nexiva™ Closed IV Catheter System enables longer dwell times and clinically indicated catheter replacement.1* A 2014 clinical study demonstrated that BD Nexiva™ catheters had a median dwell time of 144 hours for catheters in place ≥24 hours.1* The same study showed that longer dwell times of closed systems led to a cost reduction of approximately $1M/year/1,000 beds compared to an open system.1 That’s good for you and for your patients. To order or learn about all the ways BD is caring for you and your patients, visit bd.com/INS today or call (888) 237-2762. * Compared to 96 hours with an open system. 1 González López J, Arribi Vilela A, Fernández Del Palacio E, et al. Indwell times, complications BD Medical and costs of open vs closed safety peripheral intravenous catheters: a randomized study. -

Smt. B.K. Shah Medical Institute & Research Center Academic Programme Attended (Cme/Conference) : Faculty from : 01/01/2017

SUMANDEEP VIDYAPEETH DECLARED AS AN INSTITUTION DEEMED TO BE UNIVERSITY U/S 3 OF UGC ACT OF 1956 ACCREDITED - NAAC 'A' GRADE SMT. B.K. SHAH MEDICAL INSTITUTE & RESEARCH CENTER ACADEMIC PROGRAMME ATTENDED (CME/CONFERENCE) : FACULTY FROM : 01/01/2017 TO 31/12/2017 Sr. Name of Date of Venue of Level of Designation Department Name of Event Organizing Body No. Faculty Event Event Event Department of Auditorium Psychiatry Mr.K.M Assistant CME on Managing strss- SBKSMIRC 1 Anatomy 1/13/2017 SBKSMIRC State Parmar Professor defeating depression Sumandeep Sumandeep Vidyapeeth Vidyapeeth Department of Auditorium Psychiatry CME on Managing strss- SBKSMIRC 2 Mrs. Priyanka Tutor Anatomy 1/13/2017 SBKSMIRC State defeating depression Sumandeep Sumandeep Vidyapeeth Vidyapeeth Department of Auditorium Psychiatry Dr. J.M. Professor & CME on Managing strss- SBKSMIRC 3 Physiology 13/01/2017 SBKSMIRC State Harsoda Head defeating depression Sumandeep Sumandeep Vidyapeeth Vidyapeeth Department of Auditorium Psychiatry Associate CME on Managing strss- SBKSMIRC 4 Dr. Puja Dullo Physiology 13/01/2017 SBKSMIRC State Professor defeating depression Sumandeep Sumandeep Vidyapeeth Vidyapeeth Sr. Name of Date of Venue of Level of Designation Department Name of Event Organizing Body No. Faculty Event Event Event Department of Auditorium Psychiatry Mrs. G Assistant CME on Managing strss- SBKSMIRC 5 Physiology 13/01/2017 SBKSMIRC State Purohit Professor defeating depression Sumandeep Sumandeep Vidyapeeth Vidyapeeth Department of Auditorium Psychiatry Mrs. Hiral CME on Managing -

Cautious Hospitals List

Cautious Hospitals List TPA Name HospitalName Address City State GHPL TPA PULSE HOSPITAL-CHINTAL PLOT NO 10, SY NO 147P, CHINTAL HYDERABAD TELANGANA GHPL TPA MEDICHECK HOSPITAL - FARIDABAD 1C-76 AND 53, N.I.T FARIDABAD HARYANA GHPL TPA NEW MILLENNIUM MULTISPECIALITY HOSPITAL-NAVI MUMBAI PLOT NO.17C, SEC-5, SANPADA NAVI MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA GHPL TPA NANDINI HOSPITAL - SAINIKPURI PLOT NO 156, HI TENSION ROAD, SAINIKPURI X ROAD SECUNDERABAD TELANGANA GHPL TPA SAHASRA HOSPITAL(A UNIT OF SASA HEALTHCARE)-MANJEERA NAGAR MANJEERA NAGAR, MAIN ROAD SANGAREDDY TELANGANA GHPL TPA DIVYA PRASTHA HOSPITAL-PALAM COLONY RZ-37, OPPOSITE BAGH WALA SCHOOL, MAIN ROAD NEW DELHI DELHI GHPL TPA RAJPAL HOSPITAL AND INSTITUTE-KOPERKHAIRANE PLOT NO 13, SECTOR 10 NAVI MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA GHPL TPA YASHODA KRISHNA HOSPITAL - KARIMNAGAR HNO 7-1-324, MANKAMMATHOTA KARIMNAGAR TELANGANA GHPL TPA PENTAMED HOSPITAL-DELHI 7 LOCAL SHOPPING CENTRE DELHI DELHI GHPL TPA VIKAS HOSPITAL PVT LTD-NAJAFGARH 1629-H, THANA ROAD, NAJAFGARH NEW DELHI DELHI GHPL TPA JUPITER HOSPITAL - THANE EASTERN EXPRESS HIGHWAY THANE MAHARASHTRA GHPL TPA INDUS HOSPITAL - AHMEDABAD OPP. ADANI CNG PUMP, OPP. MOTERA CROSS ROAD, BRTS STOP, SABARMATI AHMEDABAD GUJARAT GHPL TPA ISHAN HOSPITAL PVT LTD-ROHINI PLOT NO. 1, POCKET -8B,SECTOER 19,ROHINI DELHI DELHI GHPL TPA ADITYA MULTICARE HOSPITAL-VISAKHAPATNAM D NO 18 7 33 OPP KGH O P GATE VISAKHAPATNAM ANDHRA PRADESH GHPL TPA BATRA HOSPITAL MEDICAL CENTRE 1 TUGHLAKABAD INSTITUTIONAL AREA NEW DELHI DELHI GHPL TPA CONTINENTAL HOSPITALS-GACHIBOWLI PLOT NO.3, ROAD -

(CLIL) in Medicine Programs in Higher Education Stapel Content and Language Integrated Learning Integrated and Language Content Stapel

GiF:on Giessener Fremdsprachendidaktik: online 6 This thesis explores the ways in which Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) with English can be implemented in medicine programs for higher education. This teaching approach emphasizes learning content Anja Stapel while simultaneously developing language skills and promoting an effective motivational learning arrangement whilst occupational language skills and knowledge of interest are acquired. The necessity for students of medicine to have a certain proficiency of English and how they can be supported in improving their language skills is discussed. Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) in Medicine Programs in Higher Education Stapel Content and Language Integrated Learning Integrated and Language Content Stapel ISBN 978-3-944682-13-6 Giessener Elektronische Bibliothek 2016 GiF:on 6 Content and Language Integrated Learning in Medicine Programs in Higher Education Giessener Fremdsprachendidaktik:online 6 Herausgegeben von Eva Burwitz-Melzer, Hélène Martinez und Franz-Joseph Meißner GiF:on Giessener Fremdsprachendidaktik:online Anja Stapel Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) in Medicine Programs in Higher Education GIESSNER ELEKTRONISCHE BIBLIOTHEK 2016 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie. Detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet unter http://www.dnb.de abrufbar. Diese Veröffentlichung ist im Internet unter folgender Creative-Commons- Lizenz publiziert: http://creative-commons.org/licences/by-nc-nd/3.0/de ISBN: 978-3-944682-13-6 URN: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hebis:26-opus-118731 Acknowledgement This master's thesis, written under the supervision of Professor Wolfgang Hallet, deals with the integration of CLIL designed English courses into medical studies. -

Infusion Therapy

INFUSION THERAPY STANDARDS OF PRACTICE Developed by Lisa Gorski, MS, RN, HHCNS-BC, CRNI®, FAAN Lynn Hadaway, MEd, RN-BC, CRNI® Mary E. Hagle, PhD, RN-BC, FAAN Mary McGoldrick, MS, RN, CRNI® Marsha Orr, MS, RN Darcy Doellman, MSN, RN, CRNI®, VA-BC REVISED 2016 315 Norwood Park South, Norwood, MA 02062 www.ins1.org Purchased by [email protected], Faye Baker From: INS Digital Press (ins.tizrapublisher.com) JIN-D-15-00057.indd 1 05/01/16 11:30 PM The Art and Science of Infusion Nursing Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice Reviewers Jeanette Adams, PhD, RN, ACNS-BC, CRNI® Alicia Mares, BSN, RN, CRNI® Steve Bierman, MD Britt Meyer, MSN, RN, CRNI®, VA-BC, NE-BC Daphne Broadhurst, BScN, RN, CVAA® Crystal Miller, MA, BSN, RN, CRNI® Wes Cetnarowski, MD Diana Montez, BSN, RN Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc Tina Morgan, BSN, RN Michael Cohen, RPh, MS, ScD(hon), DPS(hon), FASHP Russ Nassof, Esq. Ann Corrigan, MS, BSN, RN, CRNI® Barb Nickel, APRN-CNS, CRNI®, CCRN Lynn Czaplewski, MS, RN, ACNS-BC, CRNI®, Shawn O’Connell, MS, RN ® AOCNS Susan Paparella, MSN, RN ® Julie DeLisle, MSN, RN, OCN Roxanne Perucca, MSN, RN, CRNI® Michelle DeVries, MPH, CIC Ann Plohal, PhD, APRN, ACNS-BC, CRNI® ® Loretta Dorn, MSN, RN, CRNI Kathy Puglise, MSN/ED, RN, CRNI® Kimberly Duff, BSN, RN Vicky Reith, MS, RN, CNS, CEN, APRN-BC ® Cheryl Dumont, PhD, RN, CRNI Claire Rickard, PhD, RN ® Beth Fabian, BA, RN, CRNI Robin Huneke Rosenberg, MA, RN-BC, CRNI®, Stephanie Fedorinchik, BSN, RN, VA-BC VA-BC Michelle Fox, BSN, RN Diane Rutkowski, BSN, RN, CRNI® Marie Frazier, MSN, RN, CRNI® -

BSI-Conference-Booklet-2019.Pdf

Thank you to our sponsors: Janice Wright LL.B. 2 Contents Sponsors .............................................................. 02 Welcome Address ................................................ 04 Keynote Speakers…………………………………………. 06 Daily Program ...................................................... 08 Instructions for Participants ............................... 10 Abstracts Presenters .................................................... 14 Pre-Recorded ............................................... 37 Digital Posters ............................................. 74 Acknowledgements.............................................. 151 3 Welcome Address Dear Colleagues and Friends, It is with pleasure that we extend a warm welcome to all participants of the 4th International Remote Conference: Science and Society, hosted by the Beyond Sciences Initiative (BSI). This meeting will connect research scientists, educators and trainees around the globe - representatives from over 58 different countries. We look forward to hearing about scientific advances from our local and international colleagues, including the social, cultural and political contexts in which they conduct their academic activities. Our scientific program is once again notably interdisciplinary and comprehensive, with specific foci on global health, cancer, chronic diseases and biotechnology. Our goal is to enable high caliber discussions surrounding research and community activities in order to foster international collaboration. On behalf of members of Organizing Committees -

SCIENTIFIC PRESENTATION (PAPER/POSTER) : FACULTY from : 01/01/2017 to 31/12/2017 Type of Sr

SUMANDEEP VIDYAPEETH DECLARED AS AN INSTITUTION DEEMED TO BE UNIVERSITY U/S 3 OF UGC ACT OF 1956 ACCREDITED - NAAC 'A' GRADE SMT. B.K. SHAH MEDICAL INSTITUTE & RESEARCH CENTER SCIENTIFIC PRESENTATION (PAPER/POSTER) : FACULTY FROM : 01/01/2017 TO 31/12/2017 Type of Sr. Name of Title of Date of Venue of Organizing Level of Designation Department Presenta Name of Event No. Faculty Presentation Event Event Body Event tion 3rd Global World Malaria and Congress on Bhubanes 21/02/17 Congress Dr. S. J. Sickle Cell Sickle Cell hwar, 1 Professor Microbiology Paper to SCB International Lakhani Disorder: Our Disease, Odisha, 24/02/17 medical Experience Bhubaneshwar, India College Odisha, India Indian Dr. "Bioterrorism - academy of Forensic FORENSIC Kalpesh Assistant Are we Forensic 2 Medicine & Paper MEDICON 24/02/17 Mumbai National Zanzrukiy Professor prepared ?" Medicine Toxicology 2017, MUMBAI a (Oral Paper) Seth GS Medical Pulmonary 3rd Global Hypertension Congress on World Bhubanes in Sickling Sickle Cell Congress Dr.J.D. General 21-24th war , 3 Professor Paper Disorders-A Disease at SCB International Lakhani Medicine Feb 2017 Odisha , Clinical and Mayfair Lagoon , medical India Echocardiogr Bhubaneswar , College aphic study. Odisha , India Type of Sr. Name of Title of Date of Venue of Organizing Level of Designation Department Presenta Name of Event No. Faculty Presentation Event Event Body Event tion WORLDCON Association Dr Newr VAPI- Assistant General 2017, VAPI- 23-26TH of Surgeons 4 Honeypal Paper Technologies VALSAD- International Professor