2011 "It's All Write!" Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hitchhiking: the Travelling Female Body Vivienne Plumb University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2012 Hitchhiking: the travelling female body Vivienne Plumb University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Plumb, Vivienne, Hitchhiking: the travelling female body, Doctorate of Creative Arts thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2012. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3913 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Hitchhiking: the travelling female body A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctorate of Creative Arts from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by Vivienne Plumb M.A. B.A. (Victoria University, N.Z.) School of Creative Arts, Faculty of Law, Humanities & the Arts. 2012 i CERTIFICATION I, Vivienne Plumb, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Creative Arts, in the Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Journalism and Creative Writing, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Vivienne Plumb November 30th, 2012. ii Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the support of my friends and family throughout the period of time that I have worked on my thesis; and to acknowledge Professor Robyn Longhurst and her work on space and place, and I would also like to express sincerest thanks to my academic supervisor, Dr Shady Cosgrove, Sub Dean in the Creative Arts Faculty. Finally, I would like to thank the staff of the Faculty of Creative Arts, in particular Olena Cullen, Teaching and Learning Manager, Creative Arts Faculty, who has always had time to help with any problems. -

Teaching the Short Story: a Guide to Using Stories from Around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 453 CS 215 435 AUTHOR Neumann, Bonnie H., Ed.; McDonnell, Helen M., Ed. TITLE Teaching the Short Story: A Guide to Using Stories from around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1947-6 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 311p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 19476: $15.95 members, $21.95 nonmembers). PUB 'TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) Collected Works General (020) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Authors; Higher Education; High Schools; *Literary Criticism; Literary Devices; *Literature Appreciation; Multicultural Education; *Short Stories; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Comparative Literature; *Literature in Translation; Response to Literature ABSTRACT An innovative and practical resource for teachers looking to move beyond English and American works, this book explores 175 highly teachable short stories from nearly 50 countries, highlighting the work of recognized authors from practically every continent, authors such as Chinua Achebe, Anita Desai, Nadine Gordimer, Milan Kundera, Isak Dinesen, Octavio Paz, Jorge Amado, and Yukio Mishima. The stories in the book were selected and annotated by experienced teachers, and include information about the author, a synopsis of the story, and comparisons to frequently anthologized stories and readily available literary and artistic works. Also provided are six practical indexes, including those'that help teachers select short stories by title, country of origin, English-languag- source, comparison by themes, or comparison by literary devices. The final index, the cross-reference index, summarizes all the comparative material cited within the book,with the titles of annotated books appearing in capital letters. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

Stephen-King-Book-List

BOOK NERD ALERT: STEPHEN KING ULTIMATE BOOK SELECTIONS *Short stories and poems on separate pages Stand-Alone Novels Carrie Salem’s Lot Night Shift The Stand The Dead Zone Firestarter Cujo The Plant Christine Pet Sematary Cycle of the Werewolf The Eyes Of The Dragon The Plant It The Eyes of the Dragon Misery The Tommyknockers The Dark Half Dolan’s Cadillac Needful Things Gerald’s Game Dolores Claiborne Insomnia Rose Madder Umney’s Last Case Desperation Bag of Bones The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon The New Lieutenant’s Rap Blood and Smoke Dreamcatcher From a Buick 8 The Colorado Kid Cell Lisey’s Story Duma Key www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Just After Sunset The Little Sisters of Eluria Under the Dome Blockade Billy 11/22/63 Joyland The Dark Man Revival Sleeping Beauties w/ Owen King The Outsider Flight or Fright Elevation The Institute Later Written by his penname Richard Bachman: Rage The Long Walk Blaze The Regulators Thinner The Running Man Roadwork Shining Books: The Shining Doctor Sleep Green Mile The Two Dead Girls The Mouse on the Mile Coffey’s Heads The Bad Death of Eduard Delacroix Night Journey Coffey on the Mile The Dark Tower Books The Gunslinger The Drawing of the Three The Waste Lands Wizard and Glass www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Wolves and the Calla Song of Susannah The Dark Tower The Wind Through the Keyhole Talisman Books The Talisman Black House Bill Hodges Trilogy Mr. Mercedes Finders Keepers End of Watch Short -

Ingham County Board of Commissioners the County

CHAIRPERSON COUNTY SERVICES COMMITTEE SARAH ANTHONY VICTOR CELENTINO, CHAIR BRYAN CRENSHAW VICE-CHAIRPERSON MARK GREBNER CAROL KOENIG DEB NOLAN CAROL KOENIG VICE-CHAIRPERSON PRO-TEM RYAN SEBOLT RANDY MAIVILLE RANDY MAIVILLE INGHAM COUNTY BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS P.O. Box 319, Mason, Michigan 48854 Telephone (517) 676-7200 Fax (517) 676-7264 THE COUNTY SERVICES COMMITTEE WILL MEET ON TUESDAY, JANUARY 17, 2017 AT 6:00 P.M., IN THE PERSONNEL CONFERENCE ROOM (D & E), HUMAN SERVICES BUILDING, 5303 S. CEDAR, LANSING. Agenda Call to Order Approval of the December 6, 2016 Minutes Additions to the Agenda Limited Public Comment 1. Interviews - Parks Commission 2. Facilities - Emergency PO to Myers Plumbing & Heating, Inc. for Sanitary and Domestic Water Line Repairs Inside the Evidence Room at the Jail 3. Innovation and Technologies - Authorization to Start an Application Programmer above Step 2 4. Road Department a. Resolution to Approve a Professional Engineering Services Contract for the Kerns Road Salt Storage Site Closure Project with Envirosolutions, Inc. b. Resolution to Approve the Special and Routine Permits for the Ingham County Road Department c. Resolution to Approve a First Party Construction Contract with Rieth-Riley Construction Co., Inc. a Second Party Agreement with the Michigan Department of Transportation and a Third Party Agreement with Dart Container Corporation in Relation to a Road Reconstruction Project for Cedar Street from College Road to Legion Drive d. Resolution to Authorize a Service Contract with Bentley Systems, Incorporated e. Resolution Authorizing a Letter of Understanding between County of Ingham (Employer) and OPEIU Local #512 (Union) Regarding Initial Reclassification or Promotion Salary Step for the Ingham County Road Department 5. -

Representations of Mute Women in Film Honor Schwartz South Dakota State University

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Theses and Dissertations 2017 Speak, Little utM e Girl: Representations of Mute Women in Film Honor Schwartz South Dakota State University Follow this and additional works at: http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, Honor, "Speak, Little utM e Girl: Representations of Mute Women in Film" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 1665. http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/1665 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPEAK, LITTLE MUTE GIRL: REPRESENTATIONS OF MUTE WOMEN IN FILM BY HONOR SCHWARTZ A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Major in English South Dakota State University 2017 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Dr. Sharon Smith for her unwavering commitment and devotion to this project. I also greatly appreciate Dr. Teresa Hall, Dr. Nicole Flynn, and Dr. Jason McEntee, and for their time, support, and advice. This thesis would still be a figment of my imagination without these dedicated instructors. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ v Chapter One: Introduction RETHINKING THE MUTE WOMAN: VOICELESS WOMEN AND ALTERNATIVE LANGUAGES IN FILM ....................... 1 Chapter Two CLASSIC HOLLYWOOD MUTE WOMEN: JOHNNY BELINDA AND OTHER FILMS (1940s-1980s) ............................................ -

Just After Sunset: Stories Free

FREE JUST AFTER SUNSET: STORIES PDF Stephen King | 539 pages | 22 Sep 2009 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9781416586654 | English | New York, NY, United States Just After Sunset by Stephen King As guest editor of the bestselling Best American Short StoriesKing spent over a year reading hundreds of stories. His renewed passion for the form is evident on every page of Just After Sunset. Who but Stephen King would turn a Port-O-San into a slimy birth canal, Just After Sunset: Stories a roadside honky-tonk into a place for endless love? A book salesman with a grievance might pick up a mute hitchhiker, not knowing the silent man in the passenger seat listens altogether too well. Or an exercise routine on a stationary bicycle, begun to reduce bad cholesterol, might take its rider on a captivating--and then terrifying--journey. Set on a remote key in Florida, " The Gingerbread Girl " is a riveting tale featuring a young woman as vulnerable--and resourceful--as Audrey Hepburn's character in Wait Until Dark. In "Ayana," a blind girl works a miracle with a kiss and the touch of her hand. For King, the line between the living and the dead is often blurry, and the seams that hold our reality intact might tear apart at any moment. In one of the longer stories here, "N. Just After Sunset --call it dusk, call it twilight, it's a time when human intercourse takes on an unnatural cast, when nothing is quite as it Just After Sunset: Stories, when the imagination begins to reach for shadows as they dissipate to darkness and living daylight can be Just After Sunset: Stories right out of you. -

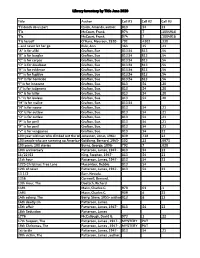

Library Inventory by Title June 2020 Title Author Call

Library Inventory by Title June 2020 Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Call #3 'Til death do us part Quick, Amanda, author. 813 .54 23 'Tis McCourt, Frank. 974 .7 .1004916 'Tis McCourt, Frank. 974 .7 .1004916 'Tis herself O'Hara, Maureen, 1920- 791 .4302 .330 --and never let her go Rule, Ann. 364 .15 .23 "A" is for alibi Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "B" is for burglar Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "C" is for corpse Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "D" is for deadbeat Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "E" is for evidence Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "F" is for fugitive Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "H" is for homicide Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "I" is for innocent Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .20 "J" is for judgment Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .20 "K" is for killer Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .20 "L" is for lawless Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .20 "M" is for malice Grafton, Sue. 813.54 "N" is for noose Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .21 "O" is for outlaw Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .21 "O" is for outlaw Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .21 "P" is for peril Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .21 "P" is for peril Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .21 "V" is for vengeance Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 22 100-year-old man who climbed out the windowJonasson, and disappeared, Jonas, 1961- The 839 .738 23 100 people who are screwing up America--andGoldberg, Al Franken Bernard, is #3 1945- 302 .23 .0973 100 years, 100 stories Burns, George, 1896- 792 .7 .028 10th anniversary Patterson, James, 1947- 813 .54 22 11/22/63 King, Stephen, 1947- 813 .54 23 11th hour Patterson, James, 1947- 813 .54 23 1225 Christmas Tree Lane Macomber, Debbie 813 .54 12th of never Patterson, James, 1947- 813 .54 23 13 1/2 Barr, Nevada. -

Department of Education, Office of Postsecondary Education June 23Rd Public Hearing

Department of Education, Office of Postsecondary Education June 23rd Public Hearing DISCLAIMER: Note: The following is the output of transcribing from a recording. Although the transcription is largely accurate, in some cases it is incomplete or inaccurate due to inaudible passages or transcription errors. It is posted as an aid to understanding the proceedings at the meeting, but should not be treated as an authoritative record. Jennifer Hong: Good morning everybody. Thank you for joining us at our virtual public hearing today, my name is Jennifer Hong, and I am the director of policy coordination in the Office of Postsecondary Education here at the Department. I'm very pleased to welcome you to today's public hearing. This is day two of three public hearings that we are convening this week. Our purpose is to gather input regarding regulations that govern programs authorized under Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965 as amended. I am joined on camera by two other Department officials: Raziya Brumfield from the office of General Counsel and Rich Williams from the Office of Postsecondary Education. So, with respect to the logistics for today's hearings I will call your name to present when it is time for you to speak. We ask that speakers limit their remarks to five minutes. If you get to the end of your 5 minutes, I will ask you to wrap up and ask that you do so within 15 seconds. If you exceed your time, you may be muted. Speakers have the option to turn on their cameras while presenting, but it is not required. -

119-2014-04-09-Wuthering Heights.Pdf

1 CHAPTER I CHAPTER II CHAPTER III CHAPTER IV CHAPTER V CHAPTER VI CHAPTER VII CHAPTER VIII CHAPTER IX CHAPTER X CHAPTER XI CHAPTER XII CHAPTER XIII CHAPTER XIV CHAPTER XV CHAPTER XVI CHAPTER XVII CHAPTER XVIII CHAPTER XIX CHAPTER XX CHAPTER XXI CHAPTER XXII CHAPTER XXIII CHAPTER XXIV CHAPTER XXV CHAPTER XXVI CHAPTER XXVII CHAPTER XXVIII CHAPTER XXIX CHAPTER XXX CHAPTER XXXI Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte 2 CHAPTER XXXII CHAPTER XXXIII CHAPTER XXXIV Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte The Project Gutenberg Etext of Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte #2 in our series by the Bronte sisters [Anne and Charlotte, too] Copyright laws are changing all over the world, be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before posting these files!! Please take a look at the important information in this header. We encourage you to keep this file on your own disk, keeping an electronic path open for the next readers. Do not remove this. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **Etexts Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *These Etexts Prepared By Hundreds of Volunteers and Donations* Information on contacting Project Gutenberg to get Etexts, and further information is included below. We need your donations. Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte December, 1996 [Etext #768] The Project Gutenberg Etext of Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte *****This file should be named wuthr10.txt or wuthr10.zip****** Corrected EDITIONS of our etexts get a new NUMBER, wuthr11.txt. VERSIONS based on separate sources get new LETTER, wuthr10a.txt. Scanned and proofed by David Price, email [email protected] We are now trying to release all our books one month in advance of the official release dates, for time for better editing. -

PDF ^ Just After Sunset: Stories » Read

Just After Sunset: Stories ^ PDF < TYPEETSO9P Just After Sunset: Stories By Stephen King Simon & Schuster. Paperback / softback. Book Condition: new. BRAND NEW, Just After Sunset: Stories, Stephen King, Stephen King -- who has written more than fifty books, dozens of number one "New York Times" bestsellers, and many unforgettable movies -- delivers an astonishing collection of short stories, his first since "Everything's Eventual" six years ago. As guest editor of the bestselling "Best American Short Stories 2007," King spent over a year reading hundreds of stories. His renewed passion for the form is evident on every page of "Just After Sunset." The stories in this collection have appeared in "The New Yorker," "Playboy," "McSweeney's," "The Paris Review," "Esquire," and other publications.Who but Stephen King would turn a Port-O- San into a slimy birth canal, or a roadside honky-tonk into a place for endless love? A book salesman with a grievance might pick up a mute hitchhiker, not knowing the silent man in the passenger seat listens altogether too well. Or an exercise routine on a stationary bicycle, begun to reduce bad cholesterol, might take its rider on a captivating -- and then terrifying -- journey. Set on a remote key in Florida, "The Gingerbread Girl" is a riveting tale featuring a young... READ ONLINE [ 6.59 MB ] Reviews It in one of my personal favorite publication. Indeed, it is actually perform, still an amazing and interesting literature. Its been printed in an exceptionally easy way which is merely soon aer i finished reading this book where really altered me, change the way i believe. -

Department of Sexuality, Women's and Gender Studies

DEPARTMENT OF SEXUALITY, WOMEN’S AND GENDER STUDIES FALL 2016 DEPARTMENT OF SEXUALITY, WOMEN’S AND GENDER STUDIES institution. More than that, though, she was a kind, Comings and Goings ever-thoughtful, beloved member of our community, filled with humaneness and strength. She will be deeply Visiting Assistant Professor Kimberly Juani- m i s s e d .” ta Brown of Mount Holyoke College will be teaching The full article can be read here: https://www. her course Self, Subject, and Photography through the amherst.edu/news/memoriam/node/583975 SWAGS Department for the Fall 2016 semester. New Course Offerings (2016-2017) Visiting Lecturer Maryam Kamali will be join- ing the SWAGS Department for the Spring 2017 semes- ter to teach Women in the Islamic Middle East. FALL 2016 SWAG 331 | The Postcolonial Novel: Gender, Race Stephanie Orion joined the and Empire SWAGS Department in August 2014 as the new Academic Department What is the novel? How do we know when a work of Coordinator. Then a little over a literature qualifies as a novel? In this course we will year later her daughter, Sylvana, study the postcolonial novel which explodes the cer- was born; the SWAGS Department’s tainties of the European novel. Written in the aftermath youngest member! of empire, these novels question race, class, gender and empire in their subject matter and narrative form. We Congratulations to Sahar Sadjadi and Khary will consider fiction from South Asia, the Caribbean Polk for being granted reappointment. Both will be on and sub-Saharan Africa. Novels include South Afri- sabbatical for the 2016-2017 academic year.