The Two Faces of Capsaicin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excluded Drug List

Excluded Drug List The following drugs are excluded from coverage as they are not approved by the FDA ACTIVE-PREP KIT I (FLURBIPROFEN-CYCLOBENZAPRINE CREAM COMPOUND KIT) ACTIVE-PREP KIT II (KETOPROFEN-BACLOFEN-GABAPENTIN CREAM COMPOUND KIT) ACTIVE-PREP KIT III (KETOPROFEN-LIDOCAINE-GABAPENTIN CREAM COMPOUND KIT) ACTIVE-PREP KIT IV (TRAMADOL-GABAPENTIN-MENTHOL-CAMPHOR CREAM COMPOUND KIT) ACTIVE-PREP KIT V (ITRACONAZOLE-PHENYTOIN SODIUM CREAM CMPD KIT) ADAZIN CREAM (BENZO-CAPSAICIN-LIDO-METHYL SALICYLATE CRE) AFLEXERYL-LC PAD (LIDOCAINE-MENTHOL PATCH) AFLEXERYL-MC PAD (CAPSAICIN-MENTHOL TOPICAL PATCH) AIF #2 DRUG PREPERATION KIT (FLURBIPROFEN-GABAPENT-CYCLOBEN-LIDO-DEXAMETH CREAM COMPOUND KIT) AGONEAZE (LIDOCAINE-PRILOCAINE KIT) ALCORTIN A (IODOQUINOL-HYDROCORTISONE-ALOE POLYSACCHARIDE GEL) ALEGENIX MIS (CAPSAICIN-MENTHOL DISK) ALIVIO PAD (CAPSAICIN-MENTHOL PATCH) ALODOX CONVENIENCE KIT (DOXYCYCLINE HYCLATE TAB 20 MG W/ EYELID CLEANSERS KIT) ANACAINE OINT (BENZOCAINE OINT) ANODYNZ MIS (CAPSAICIN-MENTHOL DISK) APPFORMIN/D (METFORMIN & DIETARY MANAGEMENT CAP PACK) AQUORAL (ARTIFICIAL SALIVA - AERO SOLN) ATENDIA PAD (LIDOCAINE-MENTHOL PATCH) ATOPICLAIR CRE (DERMATOLOGICAL PRODUCTS MISC – CREAM) Page 1 of 9 Updated JANUARY 2017 Excluded Drug List AURSTAT GEL/CRE (DERMATOLOGICAL PRODUCTS MISC) AVALIN-RX PAD (LIDOCAINE-MENTHOL PATCH) AVENOVA SPRAY (EYELID CLEANSER-LIQUID) BENSAL HP (SALICYLIC ACID & BENZOIC ACID OINT) CAMPHOMEX SPRAY (CAMPHOR-HISTAMINE-MENTHOL LIQD SPRAY) CAPSIDERM PAD (CAPSAICIN-MENTHOL -

Topical Analgesics: Expensive and Avoidable

TOPICAL ANALGESICS: EXPENSIVE AND AVOIDABLE FAST FOCUS Some very expensive topical creams and gels are creeping into the workers’ compensation Close management of custom compounds prescription files. Previously, the issue of custom compounds was highlighted and the has decreased their prevalence in workers’ attention to these prescriptions has resulted in a decrease in the number of prescriptions compensation. But private-label topicals and homeopathic products have filled the void. seen. However, the price of these compounds has increased significantly. Neither is FDA-approved. Both warrant close monitoring because of their high costs and In addition to the compounds that are still being prescribed, other topical products are lack of proven efficacy. increasingly seen in the workers’ compensation setting. In this article, a spotlight is turned on to expose more expensive topicals — private-label analgesics and homeopathic products. 24 | RxInformer FALL 2013 SUMMARY OF PRIMARY ISSUES Issue Custom Compounds Private-Label Analgesics Homeopathic Products NDCs Available FDA-approved Proven clinical benefit Prepared by compounding — — pharmacy for a specific patient Contain high levels of NSAIDs — — Contain 2-3x the FDA-approved concentration of methyl salicylate — and/or menthol Can cause skin burns — Prescribers unaware of compound ingredients Prescribers unaware of high costs Expiration dating required — — TOPICAL PRIVATE-LABEL PRODUCTS FINANCIAL CONCERNS There are private-label companies marketing products similar to inexpensive, over- When compared with comparable over-the- the-counter products, but with catchy names, inflated claims and prices. Private-label counter (OTC) preparations, the private-label topical compounds are products containing OTC ingredients such as high-potency products’ prices are stunning. -

Efficacy of Paracetamol for Acute Low-Back Pain Postherpetic

NEW ZEALAND MEDICAL JOURNAL http://www.nzma.org.nz/journal/read-the-journal/all-issues/2010-2019/2014/vol-127-no-1407/6398 METHUSELAH Efficacy of paracetamol for acute low-back pain Regular paracetamol is the recommended first-line analgesic for acute low-back pain; however, no high-quality evidence supports this recommendation. This report concerns a randomised trial concerning this hypothesis. 1652 patients with acute low-back pain were randomly assigned to receive regular doses of paracetamol, as needed doses of paracetamol, or placebo. The median time to recovery was 17 days in the regular group, 17 days in the as-needed group, and 16 days in the placebo group. Adverse effects were reported in 18.5%, 18.7%, and 18.5% in the 3 groups. No differences were noted in secondary outcomes (short-term pain relief between 1 and 12 weeks, disability, function, global rating of symptom change, sleep, or quality of life) between the 3 groups. All patients received advice to remain active, avoid bed rest, and were reassured of a favourable outcome. At 12 weeks about 85% of participants had recovered. The researchers concluded that regular or as-needed dosing with paracetamol does not affect recovery time compared with placebo in low-back pain, and question the universal endorsement of paracetamol in this patient group. Lancet 2014;384:1586–96. Postherpetic neuralgia Approximately a fifth of patients with herpes zoster report some pain at 3 months after the onset of symptoms, and 15% report pain at 2 years. Approximately 6% have a score for pain intensity of at least 30 out of 100 at both time points. -

The Effects of a Co-Application of Menthol and Capsaicin on Nociceptive Behaviors of the Rat on the Operant Orofacial Pain Assessment Device

The Effects of a Co-Application of Menthol and Capsaicin on Nociceptive Behaviors of the Rat on the Operant Orofacial Pain Assessment Device Ethan M. Anderson1,2*, Alan C. Jenkins3, Robert M. Caudle1,2, John K. Neubert3 1 Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Florida College of Dentistry, Gainesville, Florida, United States of America, 2 Department of Neuroscience, University of Florida College of Medicine, McKnight Brain Institute, Gainesville, Florida, United States of America, 3 Department of Orthodontics, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, United States of America Abstract Background: Transient receptor potential (TRP) cation channels are involved in the perception of hot and cold pain and are targets for pain relief in humans. We hypothesized that agonists of TRPV1 and TRPM8/TRPA1, capsaicin and menthol, would alter nociceptive behaviors in the rat, but their opposite effects on temperature detection would attenuate one another if combined. Methods: Rats were tested on the Orofacial Pain Assessment Device (OPAD, Stoelting Co.) at three temperatures within a 17 min behavioral session (33uC, 21uC, 45uC). Results: The lick/face ratio (L/F: reward licking events divided by the number of stimulus contacts. Each time there is a licking event a contact is being made.) is a measure of nociception on the OPAD and this was equally reduced at 45uC and 21uC suggesting they are both nociceptive and/or aversive to rats. However, rats consumed (licks) equal amounts at 33uC and 21uC but less at 45uC suggesting that heat is more nociceptive than cold at these temperatures in the orofacial pain model. When menthol and capsaicin were applied alone they both induced nociceptive behaviors like lower L/F ratios and licks. -

Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Capsicum

Journal of Ethnopharmacology 139 (2012) 228–233 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Ethnopharmacology jo urnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jethpharm Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of Capsicum baccatum: From traditional use to scientific approach a,b a a a Aline Rigon Zimmer , Bianca Leonardi , Diogo Miron , Elfrides Schapoval , c a,∗ Jarbas Rodrigues de Oliveira , Grace Gosmann a Programa de Pós-Graduac¸ ão em Ciências Farmacêuticas, Faculdade de Farmácia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Av. Ipiranga 2752, Porto Alegre, RS, 90610-000, Brazil b Laboratório de Farmacologia Aplicada, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Av. Ipiranga 6681, Porto Alegre, RS, 90619-900, Brazil c Laboratório de Biofísica Celular e Inflamac¸ ão, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Av. Ipiranga 6681, Porto Alegre, RS, 90619-900, Brazil a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Ethnopharmacological relevance: Peppers from Capsicum species (Solanaceae) are native to Central and Received 27 July 2011 South America, and are commonly used as food and also for a broad variety of medicinal applications. Received in revised form 29 October 2011 Aim of the study: The red pepper Capsicum baccatum var. pendulum is widely consumed in Brazil, but Accepted 2 November 2011 there are few reports in the literature of studies on its chemical composition and biological properties. Available online 9 November 2011 In this study the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of Capsicum baccatum were evaluated and the total phenolic compounds and flavonoid contents were determined. -

Topical Pain Relief

TOPICAL PAIN RELIEF- methyl salicylate, menthol, capsaicin cream Two Hip Consulting, LLC Disclaimer: Most OTC drugs are not reviewed and approved by FDA, however they may be marketed if they comply with applicable regulations and policies. FDA has not evaluated whether this product complies. ---------- ACTIVE INGREDIENTS Methyl salicylate 20% (16gm) Menthol 5% (4 gm) Capsaicin 0.035% (0.3gm) PURPOSE TOPICAL ANALGESIC USES For the temporary relief of minor aches and pains of muscles and joints associated with arthritis, simple backache, strains, sprains, muscle soreness and stiffness. This product does not cure any diseases. WARNINGS Warnings: For external use only. Use only as directed. Avoid contact with eyes and mucous membranes. Do not use with heating devices or pads. Do not cover or bandage tightly. If swallowed, call poison control. If contact does occur with eyes rinse with cold water and call a doctor. Discontinue use and consult a physician if condition worsens or irritation develops. Pain persists for more than 7 days. If pain clears up and then redevelops. Do not use: on cuts or infected skin, on children less than 12 years old, in combination with other topical pain products, if allergic to any ingredients, PABA, aspirin products, or sulfa. Do not use if you are pregnant or nursing. Store below 90 degrees F/32 degrees C. See USP Controlled Temperature. KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN. DIRECTIONS Use only as directed. Prior to first use, test skin sensitivity by applying a small amount. Apply and massage directly to affected area. Do not use more than 4 times a day. -

Dose-Dependent Effects of Smoked Cannabis on Capsaicin- Induced Pain and Hyperalgesia in Healthy Volunteers Mark Wallace, M.D.,* Gery Schulteis, Ph.D.,* J

Ⅵ PAIN AND REGIONAL ANESTHESIA Anesthesiology 2007; 107:785–96 Copyright © 2007, the American Society of Anesthesiologists, Inc. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. Dose-dependent Effects of Smoked Cannabis on Capsaicin- induced Pain and Hyperalgesia in Healthy Volunteers Mark Wallace, M.D.,* Gery Schulteis, Ph.D.,* J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D.,† Tanya Wolfson, M.A.,‡ Deborah Lazzaretto, M.S.,§ Heather Bentley, Ben Gouaux,# Ian Abramson, Ph.D.** Background: Although the preclinical literature suggests that nents of clinical pain makes it difficult to study these cannabinoids produce antinociception and antihyperalgesic ef- features in isolation, in terms of identifying potentially fects, efficacy in the human pain state remains unclear. Using a human experimental pain model, the authors hypothesized responsive components. Using models of experimentally that inhaled cannabis would reduce the pain and hyperalgesia induced pain in human volunteers, however, permits induced by intradermal capsaicin. simplified stimulus conditions, crossover designs, and Methods: In a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-con- comparisons between human and animal models to de- trolled, crossover trial in 15 healthy volunteers, the authors fine in parallel the physiology and pharmacology of pain evaluated concentration–response effects of low-, medium-, and high-dose smoked cannabis (respectively 2%, 4%, and 8% 9-␦- states. Therefore, one is able to investigate the sensory tetrahydrocannabinol by weight) on pain and cutaneous hyper- components of pain processing in concert with assess- algesia induced by intradermal capsaicin. Capsaicin was in- ment of analgesic efficacy. Another difficulty in some jected into opposite forearms 5 and 45 min after drug exposure, previous cannabinoid research lies in the uncertain rela- and pain, hyperalgesia, tetrahydrocannabinol plasma levels, tion of traditional experimentally induced human pain and side effects were assessed. -

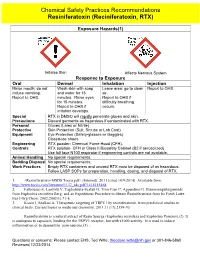

Resiniferatoxin CSPR GHS Format 2014

Chemical Safety Practices Recommendations Resiniferatoxin (Reciniferatoxin, RTX) Exposure Hazards(1) Irritates Skin Affects Nervous System Response to Exposure Oral Dermal Inhalation Injection Rinse mouth; do not Wash skin with soap Leave area; go to clean Report to OHS. induce vomiting. and water for 15 air. Report to OHS. minutes. Rinse eyes Report to OHS if for 15 minutes. difficulty breathing Report to OHS if occurs. irritation develops. Special RTX in DMSO will rapidly penetrate gloves and skin. Precautions Discard garments as hazardous if contaminated with RTX. Personal Gloves (Latex or Nitrile) Protective Skin Protection (Suit, Scrubs or Lab Coat) Equipment Eye Protection (Safety-glasses or Goggles) Closed-toe shoes Engineering RTX powder- Chemical Fume Hood (CFH). Controls RTX solution- CFH or Class II Biosafety Cabinet (B2 if aerosolized) Use full face N100 respirator if engineering controls are not available. Animal Handling No special requirements. Bedding Disposal No special requirements. Work Practices Empty RTX containers and unused RTX must be disposed of as hazardous. Follow LASP SOPs for preparation, handling, dosing, and disposal of RTX. 1. <Resiniferatoxin MSDS Tocris.pdf> [Internet]. 2011 [cited 10/9/2014]. Available from: http://www.tocris.com/literature/1137_sds.pdf?1414155468. 2. Fattorusso E, Lanzotti V, Taglialatela-Scafati O, Tron Gian C, Appendino G. Bisnorsesquiterpenoids from Euphorbia resinifera Berg. and an Expeditious Procedure to Obtain Resiniferatoxin from Its Fresh Latex. Eur J Org Chem. 2002;2002(1):71-8. 3. Kissin I, Szallasi A. Therapeutic targeting of TRPV1 by resiniferatoxin, from preclinical studies to clinical trials. Current topics in medicinal chemistry. 2011;11(17):2159-70. -

Current Medicinal Chemistry, 2017, 24, 1453-1468

Send Orders for Reprints to [email protected] 1453 Current Medicinal Chemistry, 2017, 24, 1453-1468 REVIEW ARTICLE eISSN: 1875-533X ISSN: 0929-8673 Current Impact Factor: 3.45 Medicinal Therapeutic Strategies of Plant-derived Compounds for Diabetes Via Chemistry The International Journal for Regulation of Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 Timely In-depth Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry BENTHAM SCIENCE Magdalena Czemplik1,*, Anna Kulma2, Yu Fu Wang3 and Jan Szopa2,4,5 1Department of Physico-Chemistry of Microorganisms, Institute of Genetics and Microbiology, Faculty of Biological Sciences, University of Wrocław, Wrocław, Poland; 2Faculty of Biotechnology, University of Wrocław, Wrocław, Poland; 3Institute of Bast Fiber Crops, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Changsha City, China; 4Department of Genetics, Plant Breeding and Seed Production, Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences, Wrocław, Poland; 5Linum Foundation, Wrocław, Poland Abstract: Background: Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) is a member of the CC chemokine family that plays a key role in the inflammatory process. It has been broadly stud- ied in the aspect of its role in obesity and diabetes related diseases. MCP-1 causes the infiltra- tion of macrophages into obese adipose tissue via binding to the CCR2 receptor and is in- volved in the development of insulin resistance. Methods: We reviewed the available literature regarding the importance of plant metabolites that regulate MCP-1 activity and are used in the treatment of diabetic disorders. The character- istics of screened papers were described and the important findings were included in this re- view. A R T I C L E H I S T O R Y Results: This mini-review provides a summary of functions and therapeutic strategies of this Received: October 10, 2016 chemokine, with a special focus on plant-derived compounds that possess a putative antidia- Revised: February 14, 2017 betic function via a mechanism of MCP-1 interaction. -

Capsaicin General Fact Sheet

CAPSAICIN GENERAL FACT SHEET What is capsaicin Capsaicin is the main chemical that makes chili peppers hot. Capsaicin is an animal repellent that is also used against insects and mites. Cap- saicin was first registered for use in the United States in 1962. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency considers it to be a biochemical pes- ticide because it is a naturally occurring substance. What are some products that contain capsaicin Products containing capsaicin can be aerosols, liquids, or granular formulations. There are several dozen products containing capsaicin on the market in the United States. Many of these products are animal repellents. Always follow label instructions and take steps to avoid exposure. If any exposures occur, be sure to follow the First Aid instructions on the product label carefully. For additional treat- ment advice, contact the Poison Control Center at 1-800-222-1222. If you wish to discuss a pesticide problem, please call 1-800-858-7378. How does capsaicin work Capsaicin is very irritating to the skin and eyes, and it causes swelling in lung tissue. It can also irritate the mucous membranes in the mouth. In insects and mites, it appears to damage membranes in cells and disrupt the nervous system. How might I be exposed to capsaicin Products containing capsaicin are used to deter bears and dogs. They may also be used as repellents against wildlife or pets in backyards and gardens. Other products can be used in nurseries or in agriculture. You may be exposed if you are applying capsaicin and you breathe it in or get it on your skin. -

Studies on Some Pharmacological Properties of Capsicum Frutescens-Derived Capsaicin in Experimental Animal Models

Studies on some Pharmacological Properties of Capsicum frutescens-derived capsaicin in Experimental animal Models DECLARATION I, Adebayo Taiwo Ezekiel Jolayemi (Reg. No 9903902), hereby declare that the thesis/dissertation entitled: “Studies on some Pharmacological Properties of Capsicum frutescens-derived capsaicin in Experimental animal Models” is an original work, and has not been presented in any form, for any deg to another university. Where the use was made of the works of others, it has been duly acknowledged and referenced in the text. This research was carried out in the Durban- Westville campus of the University of KwaZulu Natal using the laboratory services of Departments of Physiology, Pharmacology and the Biomedical Resource Centre. Adebayoezekieltaiwojolayemi 03/15/2012. Signature Date ii Abbreviations ANOVA Analysis of variance. (Ach) Acetylcholine. (ACEI) Angiotensin converting-enzyme-inhibitors ADT Adenine Tri phosphate (ATR) atropine 2+ Ca Calcium CaCl2 Calcium Chloride COX-2 cycloxygenase 2 receptor (CGRP) calcitonin gene-related peptide (CPF), capsaicin (CFA) complete Freund‟s adjuvant (CNS) central nervous system CFE Capsicum frutescens extract. (CPF) synthetic capsaicin (DCM) dichloromethane (DIC) diclofenac (CRP) C - reactive protein (dp/dt) Change in ventricular contraction per unit change in time (DRG) dorsal root ganglion (EAAs) excitatory amino acids (FRAP) flouride-resistant acid phosphatise G (gm) gram. (GABA) gamma-aminobutyric acid (GIT) gastro-intestinal tract (INR) Internationalised Normalised Ratio (IBD) -

Capsaicin: Current Understanding of Its Mechanisms and Therapy of Pain and Other Pre-Clinical and Clinical Uses

molecules Review Capsaicin: Current Understanding of Its Mechanisms and Therapy of Pain and Other Pre-Clinical and Clinical Uses Victor Fattori †, Miriam S. N. Hohmann †, Ana C. Rossaneis, Felipe A. Pinho-Ribeiro and Waldiceu A. Verri Jr. * Departamento de Ciências Patológicas, Centro de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Rodovia Celso Garcia Cid KM480 PR445, Caixa Postal 10.011, 86057-970 Londrina, Paraná, Brazil; [email protected] (V.F.); [email protected] (M.S.N.H.); [email protected] (A.C.R.); [email protected] (F.A.P.-R.) * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +55-43-3371-4979 † These authors contributed equally to this paper. Academic Editor: Pin Ju Chueh Received: 27 April 2016; Accepted: 27 April 2016; Published: 28 June 2016 Abstract: In this review, we discuss the importance of capsaicin to the current understanding of neuronal modulation of pain and explore the mechanisms of capsaicin-induced pain. We will focus on the analgesic effects of capsaicin and its clinical applicability in treating pain. Furthermore, we will draw attention to the rationale for other clinical therapeutic uses and implications of capsaicin in diseases such as obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular conditions, cancer, airway diseases, itch, gastric, and urological disorders. Keywords: analgesia; capsaicinoids; chili peppers; desensitization; TRPV1 1. Introduction Capsaicin is a compound found in chili peppers and responsible for their burning and irritant effect. In addition to the sensation of heat, capsaicin produces pain and, for this reason, is an important tool in the study of pain. Although our understanding of pain mechanisms has evolved greatly through the development of new techniques, experimental tools are still extremely necessary and widely used.