The Strange Art and Literature of Postmodernism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 12. the Avant-Garde in the Late 20Th Century 1

Chapter 12. The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century 1 The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century: Modernism becomes Postmodernism A college student walks across campus in 1960. She has just left her room in the sorority house and is on her way to the art building. She is dressed for class, in carefully coordinated clothes that were all purchased from the same company: a crisp white shirt embroidered with her initials, a cardigan sweater in Kelly green wool, and a pleated skirt, also Kelly green, that reaches right to her knees. On her feet, she wears brown loafers and white socks. She carries a neatly packed bag, filled with freshly washed clothes: pants and a big work shirt for her painting class this morning; and shorts, a T-shirt and tennis shoes for her gym class later in the day. She’s walking rather rapidly, because she’s dying for a cigarette and knows that proper sorority girls don’t ever smoke unless they have a roof over their heads. She can’t wait to get into her painting class and light up. Following all the rules of the sorority is sometimes a drag, but it’s a lot better than living in the dormitory, where girls have ten o’clock curfews on weekdays and have to be in by midnight on weekends. (Of course, the guys don’t have curfews, but that’s just the way it is.) Anyway, it’s well known that most of the girls in her sorority marry well, and she can’t imagine anything she’d rather do after college. -

The Tao of Postmodernism: Computer Art, Scientific Visualization and Other Paradoxes Author(S): Donna J

The Tao of Postmodernism: Computer Art, Scientific Visualization and Other Paradoxes Author(s): Donna J. Cox Source: Leonardo. Supplemental Issue, Vol. 2, Computer Art in Context: SIGGRAPH '89 Art Show Catalog (1989), pp. 7-12 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1557936 Accessed: 05/04/2010 22:26 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mitpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Leonardo. Supplemental Issue. http://www.jstor.org The Tao of Postmodernism: Computer Art, Scientific ABSTRACT The authorsuggests that a [1] paradigmshift must occur in art Visualization and Other Paradoxes criticismto assimilatethe nonlinear branchingof aesthetic activities in ourera. -

Late Modernist Versus Postmodernist Arts: Review

http://www.inosr.net/inosr-arts-and-management/ Marry and Howard INOSR ARTS AND MANAGEMENT 6(1): 55-60, 2020. ©INOSR PUBLICATIONS International Network Organization for Scientific Research ISSN: 2705-1668 Late Modernist versus Postmodernist Arts: Review Martin, Ann Ray, and Howard, Junker Department of Fine Arts, Lira University, Uganda. ABSTRACT Terms like 'modern' and 'postmodern' are subject-centered, and not based on any historical or objective phenomenon or personality. Everyone feels that something called 'Postmodernism' has happened, but, as regards its true nature and causes, opinion is divided; a few people say postmodernism is a fiction. Late modernism describes movements which arise from, and react against, trends in modernism and rejects some aspect of modernism, while fully developing the conceptual potentiality of the modernist enterprise, while postmodernism in some descriptions is a period in art which is completed, whereas in others it is a continuing movement in contemporary art. Therefore this review will check the comparison between both in the society now. Keywords: Late Modernist, Postmodernist, Arts, Society. INTRODUCTION The arts refers to the theory, human postmodernism has led to almost five application and physical expression of decades of artistic experimentation with creativity found in human cultures and new media and new art forms, including societies through skills and imagination Conceptual art, various types of in order to produce objects, environments Performance art and Installation art, as and experiences [1]. Major constituents of well as computer-aided movements like the arts include visual arts (including Deconstructivism and Projection art [4]. architecture, ceramics, drawing, Using these new forms, postmodernist filmmaking, painting, photography, and artists have stretched the definition of art sculpting), literature (including fiction, to the point where almost anything goes. -

ARTS 4301 Abstract Expressionism Through Postmodern Art Spring 2021 Professor: Dr. David A. Lewis Office Hours: MW, 10:00-12

ARTS 4301 Abstract Expressionism through Postmodern Art Spring 2021 Professor: Dr. David A. Lewis Office Hours: MW, 10:00-12:30; 3:30-5:00; TR 1:30-2:30pm, by appointment Preferred contact is by email: [email protected] Office phone: 936.468.4328 (Dr. Lewis does not use social media like Facebook or Twitter) Class meets, TR 3:30-4:45pm Livesstream ZOOM access will be available during the regular class period. Classes will be recorded on ZOOM and posted to D2L-BrightSpace for review. Recommend Text: H.H. Arnason & Elizabeth C. Mansfield, History of Modern Art, seventh edition. Pearson, 2013. NOTE: Selected required or recommended readings may be provided as handouts or with a web reference. Recommended resources: For those who want or need reference to background source for this course in Modern Art (c 1865-1945), see the earlier chapters of the textbook, Arneson/Mansfield, History of Modern Art, 7th edition. Also, very useful is Niko Stangos, editor, Concepts of Modern Art, from Fauvism to Postmodernism. Highly recommended for a fuller understanding American art of the 20th century: Patricia Hills, Modern Art in the USA, Issues and Controversies of the 20th Century. For graduate students, Harrison and Wood’s Art in Theory, 1900-2000 is unmatched as a comprehensive, single volume source for primary documents. COVID-19 MASK POLICY Masks (cloth face coverings) must be worn over the nose and mouth at all times in the classroom and appropriate physical distancing must be observed. Students not wearing a mask and/or not observing appropriate physical distancing will be asked to leave the class. -

Modernism, Postmodernism, and the Grateful Dead: the Evolution of the Psychedelic Avant-Garde Jason Robert Noe Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1996 Modernism, postmodernism, and the Grateful Dead: the evolution of the psychedelic avant-garde Jason Robert Noe Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noe, Jason Robert, "Modernism, postmodernism, and the Grateful Dead: the evolution of the psychedelic avant-garde" (1996). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16133. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16133 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modernism, postmodernism, and the Grateful Dead: the evolution of the psychedelic avant-garde by Jason Robert Noe A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department: English Major: English (Literature) Major Professor: Nina Miller Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1996 Copyright © Jason Robert Noe, 1996. All rights reserved. ii Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of Jason Robert Noe has met the requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy -

Minimalism 1 Minimalism

Minimalism 1 Minimalism Minimalism describes movements in various forms of art and design, especially visual art and music, where the work is stripped down to its most fundamental features. As a specific movement in the arts it is identified with developments in post–World War II Western Art, most strongly with American visual arts in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Prominent artists associated with this movement include Donald Judd, John McLaughlin, Agnes Martin, Dan Flavin, Robert Morris, Anne Truitt, and Frank Stella. It is rooted in the reductive aspects of Modernism, and is often interpreted as a reaction against Abstract expressionism and a bridge to Postmodern art practices. The terms have expanded to encompass a movement in music which features repetition and iteration, as in the compositions of La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, and John Adams. Minimalist compositions are sometimes known as systems music. (See also Postminimalism). The term "minimalist" is often applied colloquially to designate anything which is spare or stripped to its essentials. It has also been used to describe the plays and novels of Samuel Beckett, the films of Robert Bresson, the stories of Raymond Carver, and even the automobile designs of Colin Chapman. The word was first used in English in the early 20th century to describe the Mensheviks.[1] Minimalist design The term minimalism is also used to describe a trend in design and architecture where in the subject is reduced to its necessary elements. Minimalist design has been highly influenced by Japanese traditional design and architecture. In addition, the work of De Stijl artists is a major source of reference for this kind of work. -

Minimalism and Postminimalism

M i n i m a l i s m a n d P o s t m i n i m a l i s m : t h e o r i e s a n d r e p e r c u s s i o n s Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism 4372 The School of the Art Institute of Chicago David Getsy, Instructor [[email protected]] Spring 2000 / Tuesdays 9 am - 12 pm / Champlain 319 c o u r s e de s c r i pt i o n Providing an in-depth investigation into the innovations in art theory and practice commonly known as “Minimalism” and “Postminimalism,” the course follows the development of Minimal stylehood and tracks its far-reaching implications. Throughout, the greater emphasis on the viewer’s contribution to the aesthetic encounter, the transformation of the role of the artist, and the expanded definition of art will be examined. Close evaluations of primary texts and art objects will form the basis for a discussion. • • • m e t h o d o f e va l u a t i o n Students will be evaluated primarily on attendance, preparation, and class discussion. All students are expected to attend class meetings with the required readings completed. There will be two writing assignments: (1) a short paper on a relevant artwork in a Chicago collection or public space due on 28 March 2000 and (2) an in- class final examination to be held on 9 May 2000. The examination will be based primarily on the readings and class discussions. -

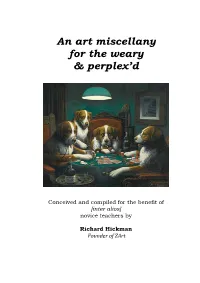

An Art Miscellany for the Weary & Perplex'd. Corsham

An art miscellany for the weary & perplex’d Conceived and compiled for the benefit of [inter alios] novice teachers by Richard Hickman Founder of ZArt ii For Anastasia, Alexi.... and Max Cover: Poker Game Oil on canvas 61cm X 86cm Cassius Marcellus Coolidge (1894) Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons [http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/] Frontispiece: (My Shirt is Alive With) Several Clambering Doggies of Inappropriate Hue. Acrylic on board 60cm X 90cm Richard Hickman (1994) [From the collection of Susan Hickman Pinder] iii An art miscellany for the weary & perplex’d First published by NSEAD [www.nsead.org] ISBN: 978-0-904684-34-6 This edition published by Barking Publications, Midsummer Common, Cambridge. © Richard Hickman 2018 iv Contents Acknowledgements vi Preface vii Part I: Hickman's Art Miscellany Introductory notes on the nature of art 1 DAMP HEMs 3 Notes on some styles of western art 8 Glossary of art-related terms 22 Money issues 45 Miscellaneous art facts 48 Looking at art objects 53 Studio techniques, materials and media 55 Hints for the traveller 65 Colours, countries, cultures and contexts 67 Colours used by artists 75 Art movements and periods 91 Recent art movements 94 World cultures having distinctive art forms 96 List of metaphorical and descriptive words 106 Part II: Art, creativity, & education: a canine perspective Introductory remarks 114 The nature of art 112 Creativity (1) 117 Art and the arts 134 Education Issues pertaining to classification 140 Creativity (2) 144 Culture 149 Selected aphorisms from Max 'the visionary' dog 156 Part III: Concluding observations The tail end 157 Bibliography 159 Appendix I 164 v Illustrations Cover: Poker Game, Cassius Coolidge (1894) Frontispiece: (My Shirt is Alive With) Several Clambering Doggies of Inappropriate Hue, Richard Hickman (1994) ii The Haywain, John Constable (1821) 3 Vagveg, Tabitha Millett (2013) 5 Series 1, No. -

Research on Art Creative Teaching-A Case Study of Design And

International Journal of Affective Engineering Vol.18 No.4 pp.205-214 (2019) doi: 10.5057/ijae.IJAE-D-18-00010 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Research on Art Creative Teaching – A Case Study of Design and Teaching Activities of Elementary Students in Taiwan – Li-Chun HUANG*, Ming-Chuan HO** and Thomas Chiang BLAIR*** * Graduate School of Design, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, 6F-2, No.55, Sec. 1, Zhonghua Rd.,Taichung City 40041, Taiwan (R.O.C.) ** National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, Taiwan *** National Taipei University of Education, Taiwan Abstract: The education theories in Taiwan during the last 30 years are heavily influenced by trends of postmodern art. Therefore, design teaching that emphasizes practicality has received more attention in national art curriculum. The first author is an elementary school art teacher who have planned T-shirt-design activity for the last 6 years, to analyze students’ design abilities and aesthetic expression in the pseudorealistic stage. On this research, the results of questionnaires were analysis with SPSS 18.0, and interviews were also conducted. The results revealed 77% of students were able to create variations of the provided motifs, reflecting their abilities to create their own designs. The students tended to use pure and warm colors required guidance to create complicated designs. The students demonstrated ability to use Chinese, English, and numbers to convey their thoughts and feelings. The results also showed that the T-shirt-design creative teaching activity could stimulate elementary students’ creativity. Keywords: Elementary school design education, Design creative teaching, Contemporary artistic trend In 2001, the 9-year mandatory education policy was 1. -

Why Art Became Ugly Stephen R

Why Art Became Ugly Stephen R. C. Hicks For a long time critics of modern and postmodern art have relied on the “Isn’t that disgusting” strategy. By that I mean the strategy of pointing out that given works of art are ugly, trivial, or in bad taste, that “a five-year-old could have made them,” and so on. And they have mostly left it at that. The points have often been true, but they have also been tiresome and unconvincing—and the high-art world has been entirely unmoved. Of course, the major works of the twentieth-century art world are ugly. Of course, many are offensive. Of course, a five-year old could in many cases have made an indistinguishable product. Those points are not arguable—and they are entirely beside the main question. The important question is: Why has the high-art world of the twentieth- and early twenty-first centuries adopted the ugly and the offensive? Why has it poured its creative energies and cleverness into the trivial, the mocking, and the self-proclaimedly meaningless? It is easy to point out the psychologically disturbed or cynical players who learn to manipulate the system to get their fifteen minutes or a nice big check from a foundation, or the hangers-on who play the game in order to get invited to the right parties. But every human field of endeavor has its hangers-on, its disturbed and cynical members, and they are never the ones who drive the scene. The question is: Why did cynicism and ugliness come to be the game you had to play to make it in the world of art? The flipside of that question is why representational art became a non-player. -

The Postmodernist Descending the Staircase. INSTITUTION Australian Inst

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 455 155 SO 032 041 AUTHOR Paterson, Susan TITLE The Postmodernist Descending the Staircase. INSTITUTION Australian Inst. of Art Education, Melbourne. PUB DATE 1999-09-00 NOTE 8p.; Paper presented at the Annual World Congress of the International Society for Education through Art (InSEA) (30th, Brisbane, Australia, September 21-26, 1999). Paper assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council for the Arts. AVAILABLE FROM Australian Institute of Art Education, C/Suite 125, 283 Glenhuntley Road, Eisternwick, VIC 3185, Australia. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070)-- Opinion Papers (120) Speeches /Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Aesthetics; *Art Education; Art Expression; *Art History; *Visual Arts IDENTIFIERS Baudrillard (Jean); Bourdieu (Pierre); Dadaism; Derrida (Jacques); *Duchamp (Marcel); Theoretical Analysis ABSTRACT This paper considers the artistic and literary movement called "Postmodernism." Noting that postmodernism is intellectually grounded in the premise that its discourse must expose positions of privilege and power relations in society, the paper asks of art education, How much has the postmodern condition, a thesis of cultural relativism that denies that we can step outside of custom to judge custom, affected our domain? The paper first discusses the early 20th-century movement called "Dada" as a precursor to the postmodern condition. It explores Marcel Duchamp's "art making," when he abandoned painting and began to work with industrial or commercially produced materials that suited the expression of his ideas and his iconoclasm. Duchamp attempted to escape the realm of aesthetics, but in doing so he created a new aesthetic field. The paper then discusses the ideas of several postmodern theorists, including Pierre Bourdieu, Jean Baudrillard, Jacques Derrida, Arthur Danto, Fredric Jameson, and Robert Dixon. -

Dadaism Curtis Carter Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Philosophy Faculty Research and Publications Philosophy, Department of 1-1-1998 Dadaism Curtis Carter Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. "Dadaism," in Encyclopedia of Aesthetics. Eds. Michael Kelly. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998: 487-490. Permalink. © 2012 Oxford University Press. Used with permission. Dadaism Apart from its anecdotal place as a colorful moment in the history of art and aesthetics, Dada, for better or worse, significantly changed the concepts and practices of art in the twentieth century. The noisy debates and wild theatrics of the Dadaists across Europe, and the work and writings of Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, and Francis Picabia, among others, raised profound conceptual challenges that altered the course of art and aesthetics in the twentieth century. The shift from the idea of art as a selection of attractive visual objects to art as a vehicle for ideas forced artists and aestheticians to reexamine and modify their thinking about the very concept of art, as well as its practice. The upheaval fostered by the Dadaists has called into question all essentialist definitions of art (such as Plato's mimetic theory of representation), as well as the formalist and Expressionist theories that were advanced during the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries. Modern theories espousing the purity of art media such as painting also would have found no favor with the Dadaists. In contrast to modernist purity, their practices fostered the dissolution of the boundaries of the separate art media. The combined assault of wild, irreverent Dadaist experiments with the cool but deadly wit of the likes of Duchamp and Man Ray called into question all assumptions about art.