Dissolving the Boundaries: Postmodern Art and Art Therapy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy in the Artworld: Some Recent Theories of Contemporary Art

philosophies Article Philosophy in the Artworld: Some Recent Theories of Contemporary Art Terry Smith Department of the History of Art and Architecture, the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA; [email protected] Received: 17 June 2019; Accepted: 8 July 2019; Published: 12 July 2019 Abstract: “The contemporary” is a phrase in frequent use in artworld discourse as a placeholder term for broader, world-picturing concepts such as “the contemporary condition” or “contemporaneity”. Brief references to key texts by philosophers such as Giorgio Agamben, Jacques Rancière, and Peter Osborne often tend to suffice as indicating the outer limits of theoretical discussion. In an attempt to add some depth to the discourse, this paper outlines my approach to these questions, then explores in some detail what these three theorists have had to say in recent years about contemporaneity in general and contemporary art in particular, and about the links between both. It also examines key essays by Jean-Luc Nancy, Néstor García Canclini, as well as the artist-theorist Jean-Phillipe Antoine, each of whom have contributed significantly to these debates. The analysis moves from Agamben’s poetic evocation of “contemporariness” as a Nietzschean experience of “untimeliness” in relation to one’s times, through Nancy’s emphasis on art’s constant recursion to its origins, Rancière’s attribution of dissensus to the current regime of art, Osborne’s insistence on contemporary art’s “post-conceptual” character, to Canclini’s preference for a “post-autonomous” art, which captures the world at the point of its coming into being. I conclude by echoing Antoine’s call for artists and others to think historically, to “knit together a specific variety of times”, a task that is especially pressing when presentist immanence strives to encompasses everything. -

Contemporary Art in Indian Context

Artistic Narration, Vol. IX, 2018, No. 2: ISSN (P) : 0976-7444 (e) : 2395-7247Impact Factor 6.133 (SJIF) Contemporary Art in Indian Context Dr. Hemant Kumar Rai Richa Singh Asso. Prof., Research Scholar Deptt. of Drawing & Painting M.F.A. M.M.H. College B.Ed. Ghaziabad, U.P. Reference to this paper should be made as follows: Abstract: This article has a focus on Contemporary Art in Indian context. Dr. Hemant Kumar Rai Through this article emphasizesupon understanding the changes in Richa Singh, Contemporary Art over a period of time in India right from its evolution to the economic liberalization period than in 1990’s and finally in the Contemporary Art in current 21st century. The article also gives an insight into the various Indian Context, techniques and methods adopted by Indian Contemporary Artists over a period of time and how the different generations of artists adopted different techniques in different genres. Finally the article also gives an insight Artistic Narration 2018, into the current scenario of Indian Contemporary Art and the Vol. IX, No.2, pp.35-39 Contemporary Artists reach to the world economy over a period of time. key words: Contemporary Art, Contemporary Artists, Indian Art, 21st http://anubooks.com/ Century Art, Modern Day Art ?page_id=485 35 Contemporary Art in Indian Context Dr. Hemant Kumar Rai, Richa Singh Contemporary Art Contemporary Art refers to art – namely, painting, sculpture, photography, installation, performance and video art- produced today. Though seemingly simple, the details surrounding this definition are often a bit fuzzy, as different individuals’ interpretations of “today” may widely vary. -

Ffdoespieszak Pieszak CRITICAL REALISM in CONTEMPORARY ART by Alexandra Oliver BFA, Ryerson University, 2005 MA, University of E

CRITICAL REALISM IN CONTEMPORARY ART by Alexandra Oliver BFA, Ryerson University, 2005 MA, University of Essex, 2007 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2014 FfdoesPieszak Pieszak UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Alexandra Oliver It was defended on April 1, 2014 and approved by Terry Smith, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Contemporary Art History and Theory, History of Art & Architecture Barbara McCloskey, Associate Professor, History of Art & Architecture Daniel Morgan, Associate Professor, Department of Cinema and Media Studies, University of Chicago Dissertation Advisor: Josh Ellenbogen, Associate Professor, History of Art & Architecture ii Copyright © by Alexandra Oliver 2014 iii CRITICAL REALISM IN CONTEMPORARY ART Alexandra Oliver, Ph.D. University of Pittsburgh, 2014 This study responds to the recent reappearance of realism as a viable, even urgent, critical term in contemporary art. Whereas during the height of postmodern semiotic critique, realism was taboo and documentary could only be deconstructed, today both are surprisingly vital. Nevertheless, recent attempts to recover realism after poststructuralism remain fraught, bound up with older epistemological and metaphysical concepts. This study argues instead for a “critical realism” that is oriented towards problems of ethics, intersubjectivity, and human rights. Rather than conceiving of realism as “fit” or identity between representation and reality, it is treated here as an articulation of difference, otherness and non-identity. This new concept draws on the writings of curator Okwui Enwezor, as well as German critical theory, to analyze the work of three artists: Ian Wallace (b. -

Metamodern Writing in the Novel by Thomas Pynchon

INTERLITT ERA RIA 2019, 24/2: 495–508 495 Bleeding Edge of Postmodernism Bleeding Edge of Postmoder nism: Metamodern Writing in the Novel by Thomas Pynchon SIMON RADCHENKO Abstract. Many different models of co ntemporary novel’s description arose from the search for methods and approaches of post-postmodern texts analysis. One of them is the concept of metamodernism, proposed by Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker and based on the culture and philosophy changes at the turn of this century. This article argues that the ideas of metamodernism and its main trends can be successfully used for the study of contemporary literature. The basic trends of metamodernism were determined and observed through the prism of literature studies. They were implemented in the analysis of Thomas Pynchon’s latest novel, Bleeding Edge (2013). Despite Pynchon being usually considered as postmodern writer, the use of metamodern categories for describing his narrative strategies confirms the idea of the novel’s post-postmodern orientation. The article makes an endeavor to use metamodern categories as a tool for post-postmodern text studies, in order to analyze and interpret Bleeding Edge through those categories. Keywords: meta-modernism; postmodernism; Thomas Pynchon; oscillation; new sincerity How can we study something that has not been completely described yet? Although discussions of a paradigm shift have been around long enough, when talking about contemporary literary phenomena we are still using the categories of feeling rather than specific instruments. Perception of contemporary lit era- ture as post-postmodern seems dated today. However, Joseph Tabbi has questioned the novelty of post-postmodernism as something new, different from postmodernism and proposes to consider the abolition of irony and post- modernism (Tabbi 2017). -

Modernism 1 Modernism

Modernism 1 Modernism Modernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes the modernist movement, its set of cultural tendencies and array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Modernism was a revolt against the conservative values of realism.[2] [3] [4] Arguably the most paradigmatic motive of modernism is the rejection of tradition and its reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody in new forms.[5] [6] [7] Modernism rejected the lingering certainty of Enlightenment thinking and also rejected the existence of a compassionate, all-powerful Creator God.[8] [9] In general, the term modernism encompasses the activities and output of those who felt the "traditional" forms of art, architecture, literature, religious faith, social organization and daily life were becoming outdated in the new economic, social, and political conditions of an Hans Hofmann, "The Gate", 1959–1960, emerging fully industrialized world. The poet Ezra Pound's 1934 collection: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. injunction to "Make it new!" was paradigmatic of the movement's Hofmann was renowned not only as an artist but approach towards the obsolete. Another paradigmatic exhortation was also as a teacher of art, and a modernist theorist articulated by philosopher and composer Theodor Adorno, who, in the both in his native Germany and later in the U.S. During the 1930s in New York and California he 1940s, challenged conventional surface coherence and appearance of introduced modernism and modernist theories to [10] harmony typical of the rationality of Enlightenment thinking. -

Metamodernism, Or Exploring the Afterlife of Postmodernism

“We’re Lost Without Connection”: Metamodernism, or Exploring the Afterlife of Postmodernism MA Thesis Faculty of Humanities Media Studies MA Comparative Literature and Literary Theory Giada Camerra S2103540 Media Studies: Comparative Literature and Literary Theory Leiden, 14-06-2020 Supervisor: Dr. M.J.A. Kasten Second reader: Dr.Y. Horsman Master thesis submitted in accordance with the regulations of Leiden University 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER 1: Discussing postmodernism ........................................................................................ 10 1.1 Postmodernism: theories, receptions and the crisis of representation ......................................... 10 1.2 Postmodernism: introduction to the crisis of representation ....................................................... 12 1.3 Postmodern aesthetics ................................................................................................................. 14 1.3.1 Sociocultural and economical premise ................................................................................. 14 1.3.2 Time, space and meaning ..................................................................................................... 15 1.3.3 Pastiche, parody and nostalgia ............................................................................................ -

Outline of a Sociological Theory of Art Perception∗

From: Pierre Bordieu The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature ©1984, Columbia University Press Part III: The Pure Gaze: Essays on Art, Chapter 8 Outline of a Sociological Theory of Art Perception∗ PIERRE BOURDIEU 1 Any art perception involves a conscious or unconscious deciphering operation. 1.1 An act of deciphering unrecognized as such, immediate and adequate ‘comprehension’, is possible and effective only in the special case in which the cultural code which makes the act of deciphering possible is immediately and completely mastered by the observer (in the form of cultivated ability or inclination) and merges with the cultural code which has rendered the work perceived possible. Erwin Panofsky observes that in Rogier van der Weyden’s painting The Three Magi we immediately perceive the representation of an apparition’ that of a child in whom we recognize ‘the Infant Jesus’. How do we know that this is an apparition? The halo of golden rays surrounding the child would not in itself be sufficient proof, because it is also found in representations of the nativity in which the Infant Jesus is ‘real’. We come to this conclusion because the child is hovering in mid-air without visible support, and we do so although the representation would scarcely have been different had the child been sitting on a pillow (as in the case of the model which Rogier van der Weyden probably used). But one can think of hundreds of pictures in which human beings, animals or inanimate objects appear to be hovering in mid-air, contrary to the law of gravity, yet without giving the impression of being apparitions. -

Chapter 12. the Avant-Garde in the Late 20Th Century 1

Chapter 12. The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century 1 The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century: Modernism becomes Postmodernism A college student walks across campus in 1960. She has just left her room in the sorority house and is on her way to the art building. She is dressed for class, in carefully coordinated clothes that were all purchased from the same company: a crisp white shirt embroidered with her initials, a cardigan sweater in Kelly green wool, and a pleated skirt, also Kelly green, that reaches right to her knees. On her feet, she wears brown loafers and white socks. She carries a neatly packed bag, filled with freshly washed clothes: pants and a big work shirt for her painting class this morning; and shorts, a T-shirt and tennis shoes for her gym class later in the day. She’s walking rather rapidly, because she’s dying for a cigarette and knows that proper sorority girls don’t ever smoke unless they have a roof over their heads. She can’t wait to get into her painting class and light up. Following all the rules of the sorority is sometimes a drag, but it’s a lot better than living in the dormitory, where girls have ten o’clock curfews on weekdays and have to be in by midnight on weekends. (Of course, the guys don’t have curfews, but that’s just the way it is.) Anyway, it’s well known that most of the girls in her sorority marry well, and she can’t imagine anything she’d rather do after college. -

Resource What Is Modern and Contemporary Art

WHAT IS– – Modern and Contemporary Art ––– – –––– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ––– – – – – ? www.imma.ie T. 00 353 1 612 9900 F. 00 353 1 612 9999 E. [email protected] Royal Hospital, Military Rd, Kilmainham, Dublin 8 Ireland Education and Community Programmes, Irish Museum of Modern Art, IMMA THE WHAT IS– – IMMA Talks Series – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ? There is a growing interest in Contemporary Art, yet the ideas and theo- retical frameworks which inform its practice can be complex and difficult to access. By focusing on a number of key headings, such as Conceptual Art, Installation Art and Performance Art, this series of talks is intended to provide a broad overview of some of the central themes and directions in Modern and Contemporary Art. This series represents a response to a number of challenges. Firstly, the 03 inherent problems and contradictions that arise when attempting to outline or summarise the wide-ranging, constantly changing and contested spheres of both art theory and practice, and secondly, the use of summary terms to describe a range of practices, many of which emerged in opposition to such totalising tendencies. CONTENTS Taking these challenges into account, this talks series offers a range of perspectives, drawing on expertise and experience from lecturers, artists, curators and critical writers and is neither definitive nor exhaustive. The inten- What is __? talks series page 03 tion is to provide background and contextual information about the art and Introduction: Modern and Contemporary Art page 04 artists featured in IMMA’s exhibitions and collection in particular, and about How soon was now? What is Modern and Contemporary Art? Contemporary Art in general, to promote information sharing, and to encourage -Francis Halsall & Declan Long page 08 critical thinking, debate and discussion about art and artists. -

MF-Romanticism .Pdf

Europe and America, 1800 to 1870 1 Napoleonic Europe 1800-1815 2 3 Goals • Discuss Romanticism as an artistic style. Name some of its frequently occurring subject matter as well as its stylistic qualities. • Compare and contrast Neoclassicism and Romanticism. • Examine reasons for the broad range of subject matter, from portraits and landscape to mythology and history. • Discuss initial reaction by artists and the public to the new art medium known as photography 4 30.1 From Neoclassicism to Romanticism • Understand the philosophical and stylistic differences between Neoclassicism and Romanticism. • Examine the growing interest in the exotic, the erotic, the landscape, and fictional narrative as subject matter. • Understand the mixture of classical form and Romantic themes, and the debates about the nature of art in the 19th century. • Identify artists and architects of the period and their works. 5 Neoclassicism in Napoleonic France • Understand reasons why Neoclassicism remained the preferred style during the Napoleonic period • Recall Neoclassical artists of the Napoleonic period and how they served the Empire 6 Figure 30-2 JACQUES-LOUIS DAVID, Coronation of Napoleon, 1805–1808. Oil on canvas, 20’ 4 1/2” x 32’ 1 3/4”. Louvre, Paris. 7 Figure 29-23 JACQUES-LOUIS DAVID, Oath of the Horatii, 1784. Oil on canvas, approx. 10’ 10” x 13’ 11”. Louvre, Paris. 8 Figure 30-3 PIERRE VIGNON, La Madeleine, Paris, France, 1807–1842. 9 Figure 30-4 ANTONIO CANOVA, Pauline Borghese as Venus, 1808. Marble, 6’ 7” long. Galleria Borghese, Rome. 10 Foreshadowing Romanticism • Notice how David’s students retained Neoclassical features in their paintings • Realize that some of David’s students began to include subject matter and stylistic features that foreshadowed Romanticism 11 Figure 30-5 ANTOINE-JEAN GROS, Napoleon at the Pesthouse at Jaffa, 1804. -

CUBISM and ABSTRACTION Background

015_Cubism_Abstraction.doc READINGS: CUBISM AND ABSTRACTION Background: Apollinaire, On Painting Apollinaire, Various Poems Background: Magdalena Dabrowski, "Kandinsky: Compositions" Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art Background: Serial Music Background: Eugen Weber, CUBISM, Movements, Currents, Trends, p. 254. As part of the great campaign to break through to reality and express essentials, Paul Cezanne had developed a technique of painting in almost geometrical terms and concluded that the painter "must see in nature the cylinder, the sphere, the cone:" At the same time, the influence of African sculpture on a group of young painters and poets living in Montmartre - Picasso, Braque, Max Jacob, Apollinaire, Derain, and Andre Salmon - suggested the possibilities of simplification or schematization as a means of pointing out essential features at the expense of insignificant ones. Both Cezanne and the Africans indicated the possibility of abstracting certain qualities of the subject, using lines and planes for the purpose of emphasis. But if a subject could be analyzed into a series of significant features, it became possible (and this was the great discovery of Cubist painters) to leave the laws of perspective behind and rearrange these features in order to gain a fuller, more thorough, view of the subject. The painter could view the subject from all sides and attempt to present its various aspects all at the same time, just as they existed-simultaneously. We have here an attempt to capture yet another aspect of reality by fusing time and space in their representation as they are fused in life, but since the medium is still flat the Cubists introduced what they called a new dimension-movement. -

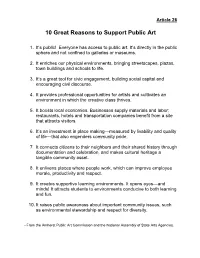

10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art

Article 26 10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art 1. It’s public! Everyone has access to public art. It’s directly in the public sphere and not confined to galleries or museums. 2. It enriches our physical environments, bringing streetscapes, plazas, town buildings and schools to life. 3. It’s a great tool for civic engagement, building social capital and encouraging civil discourse. 4. It provides professional opportunities for artists and cultivates an environment in which the creative class thrives. 5. It boosts local economies. Businesses supply materials and labor; restaurants, hotels and transportation companies benefit from a site that attracts visitors. 6. It’s an investment in place making—measured by livability and quality of life—that also engenders community pride. 7. It connects citizens to their neighbors and their shared history through documentation and celebration, and makes cultural heritage a tangible community asset. 8. It enlivens places where people work, which can improve employee morale, productivity and respect. 9. It creates supportive learning environments. It opens eyes—and minds! It attracts students to environments conducive to both learning and fun. 10. It raises public awareness about important community issues, such as environmental stewardship and respect for diversity. --From the Amherst Public Art Commission and the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies. The Amherst Public Art Commission Why Public Art for Amherst? Public art adds enormous value to the cultural, aesthetic and economic vitality of a community. It is now a well-accepted principle of urban design that public art contributes to a community’s identity, fosters community pride and a sense of belonging, and enhances the quality of life for its residents and visitors.