15Th EBHA Annual Conference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Stavros Niarchos Foundation Lecture Brochure

World Trade and Exchange Rates From the Pax Americana to a Multilateral New Order LORD MERVYN KING Former Governor of the Bank of England SEVENTEENTH ANNUAL STAVROS NIARCHOS FOUNDATION LECTURE AND DINNER TUESDAY, MAY 16, 2017 About the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Lecture Series The annual Stavros Niarchos Foundation Lecture Series at the Peterson Institute for International Economics was established in 2001 through the generous support of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation. The Series enables the Institute to present a leader of world economic policy and thinking for a major address each year on a topic of central concern to the US and international policy communities. The Series’ inaugural lecture was delivered by Alan Greenspan, former chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, in 2001. The list of subsequent speakers includes Ernesto Zedillo, former President of Mexico, in 2003; Lawrence H. Summers, former Secretary of the Treasury and Chair of the National Economic Council, in 2004; Long Yongtu, former Vice Minister of China’s Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation, in 2005; Mario Monti, former Prime Minister of Italy, in 2006; Heizō Takenaka, former Minister for Economic Policy of Japan, in 2007; Petr Aven, former President of Alfa Bank, in 2008; Nandan M. Nilekani, former Co- Chairman of the Board of Directors, Infosys Technologies, LTD, in 2009; Niall Ferguson, Laurence A. Tisch Professor of History, Harvard University, in 2010; John Lipsky, former First Deputy Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund, in 2011; -

E Onassis Marriage and the Hellenization of an American Icon

Jackie the Greek: e Onassis Marriage and the Hellenization of an American Icon David Wills | Neograeca Bohemica | 20 | 2020 | 9–23 | Abstract A 1968 series of satirical audio sketches concerning the marriage and lifestyle of Aristotle Onassis and Jacqueline Kennedy provides an opportunity to re- -examine the reputation of this famous couple. ese recordings connect with well-known negative assumptions – both in the contemporaneous media and in the previously restricted governmental fi les from the British National Archives used here – about Kennedy’s cynicism and Onassis’ Greek heritage. It will also be argued here that Jackie’s attempts to engage with Greece, especially Modern Greece, were a deliberate choice as part of her new identity, but in reality mere- ly contributed to her damaged image. Keywords Onassis, Hellenism, American satire, Skorpios, Greek shipowners 10 | David Wills In the 1960s Jacqueline Bouvier made the journey from American idol to fallen Greek goddess. Already in her time as First Lady, she had introduced Ancient Greek culture to JFK, leading to the adoption of classical themes in Presidential rhetoric and antique gowns at White House balls. Her subsequent marriage to Aristotle Onassis enabled her to become part of Modern Greece too. But al- though Jackie delighted in exploring her adopted country’s lifestyle, becoming a Modern Greek had its pitfalls as well as practical benefi ts. It caused widespread damage to her reputation amongst the American media and public. is was not merely because of her marriage to a wealthy, older man. It was also be- cause being a Modern Greek did not have the same perceived cultural value as ‘Ancient’. -

CHANIA, CRETE ERASMUS+/KA2 “Education, Profession and European Citizenship” Project 1 Transnational Meeting Alikianos

CHANIA, CRETE ERASMUS+/KA2 “Education, Profession and European Citizenship” Project 1st Transnational Meeting Alikianos, Chania, Crete, GREECE 24.10-27.10.2016 In co-operation with schools from Greece, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia ΓΕΝΙΚΟ ΛΥΚΕΙΟ ΑΛΙΚΙΑΝΟΥ ΧΑΝΙΩΝ GREECE IN A NUT SHELL Greece (Greek: Ελλάδα, Elláda [eˈlaða]), officially the Hellenic Republic (Greek: Ελληνική Δημοκρατία Ell a a [eliniˈci ðimokraˈti.a]), also known since ancient times as Hellas (Ancient Greek: Ἑλλάς Hellás [ˈhɛləs]), is a transcontinental country located in southeastern Europe. Greece's population is approximately 10.9 million as of 2015. Athens is the nation's capital and largest city, followed by Thessaloniki. Greece is strategically located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Situated on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, the Republic of Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to the northeast. Greece consists of nine geographic regions: Macedonia, Central Greece, the Peloponnese, Thessaly, Epirus, the Aegean Islands (including the Dodecanese and Cyclades), Thrace, Crete, and the Ionian Islands. The Aegean Sea lies to the east of the mainland, the Ionian Sea to the west, the Cretan Sea and the Mediterranean Sea to the south. Greece has the longest coastline on the Mediterranean Basin and the 11th longest coastline in the world at 13,676 km (8,498 mi) in length, featuring a vast number of islands, of which 227 are inhabited. Eighty percent of Greece is mountainous, with Mount Olympus being the highest peak at 2,918 meters (9,573 ft). The history of Greece is one of the longest of any country, having been continuously inhabited since 270,000 BC. -

How Aristotle Onassis Made His First Million in Argentina

How Aristotle Onassis Made His First Million in Argentina (Reprinted from Brandstand Summer 2007) Many people are familiar with the story of how a vast fortune was amassed by Aristotle Onassis in his lifetime through control of a worldwide shipping empire but few are aware that his first million was earned making cigarettes in Argentina during the late 1920s and early 1930s. The story of this early cigarette manufacturing venture reveals much about the way Onassis would approach the business world all his life. Aristotle Onassis spent his early years in the city of Smirne in the province of Anatolia. His father, Socrates had moved to the bustling trade port after hearing stories of the numerous economic opportunities there. He had started up a small import-export shop dealing in cotton, figs, rugs and tobacco and his business soon flourished. With his three brothers as partners, Socrates expanded the business repeatedly and then began to focus on tobacco as their principal commodity. Socrates Onassis married the daughter of a village notable around 1898 and Aristotle and his brother Artemide were born within the next two years. Young Ari and his brother grew up during a period of hostilities between Greek and Turkish nationalists. The area where they lived was occupied by Turkey in 1909 and remained so throughout WWI. After the war, Greece was encouraged to reoccupy Smirne and they did so. However, the reoccupation was short-lived and in 1927, Turkish troops under command of Kemal Pascia conquered the territory once again. Socrates Onassis was thrown into a Turkish prison for his Greek nationalist activities. -

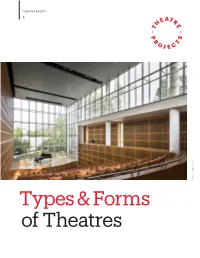

Types & Forms of Theatres

THEATRE PROJECTS 1 Credit: Scott Frances Scott Credit: Types & Forms of Theatres THEATRE PROJECTS 2 Contents Types and forms of theatres 3 Spaces for drama 4 Small drama theatres 4 Arena 4 Thrust 5 Endstage 5 Flexible theatres 6 Environmental theatre 6 Promenade theatre 6 Black box theatre 7 Studio theatre 7 Courtyard theatre 8 Large drama theatres 9 Proscenium theatre 9 Thrust and open stage 10 Spaces for acoustic music (unamplified) 11 Recital hall 11 Concert halls 12 Shoebox concert hall 12 Vineyard concert hall, surround hall 13 Spaces for opera and dance 14 Opera house 14 Dance theatre 15 Spaces for multiple uses 16 Multipurpose theatre 16 Multiform theatre 17 Spaces for entertainment 18 Multi-use commercial theatre 18 Showroom 19 Spaces for media interaction 20 Spaces for meeting and worship 21 Conference center 21 House of worship 21 Spaces for teaching 22 Single-purpose spaces 22 Instructional spaces 22 Stage technology 22 THEATRE PROJECTS 3 Credit: Anton Grassl on behalf of Wilson Architects At the very core of human nature is an instinct to musicals, ballet, modern dance, spoken word, circus, gather together with one another and share our or any activity where an artist communicates with an experiences and perspectives—to tell and hear stories. audience. How could any one kind of building work for And ever since the first humans huddled around a all these different types of performance? fire to share these stories, there has been theatre. As people evolved, so did the stories they told and There is no ideal theatre size. The scale of a theatre the settings where they told them. -

Aristotle Onassis Part 1 of 10

4 ii -I L 1 592 1 § FEDERAL BUREAU OF iNVESTiGAT1ON 1 ARISTOTLE ONASSIS -cw; A t-mi- 4 l92i'-II I PART 1 UF 4 BUFILE: 100-125834 '_;:1 &-_-_-_-.7..i_....V....._______, -_-..._ ____ .V__r_'" '- , _ 7 . |- Q I . * .92 __ _'_# Y _-_._: 5.-e l ._ ' . _ iv _ '/ -. ; _ - _ .. -~ .. _ K ; - . '4' Ki ' i ii .. - 111 . _ if L v - . I , 4 ' v n »92 _ ¢_:.~1=~. ! ._ tn;- _- = ..-. 92 ' Q ' Y" -. 15 - _ v W 9 ' . '. 1:-L-1 f..-"* TQ. -" '_ V _ ' ' - <'* '4|-| - |_492 .- . -.".r v_ '_. 7 .__.. ____ .__..... ;.__.____.__....... _ s. ..__ 7 _ _ _ _ - -0_ I _ " l . 1? '1 1" ONAS-'5I$ , Aristetslis v CHI SUBJECT is a Greekwho was scheduled to departfrom -'1-:;;_ , E " Bushes hires "£'orthe U,S, on -Tune 18 by Pe.n:-air. He '. .-'-_. _. 3' - ope"is a partwhich ownerhe hopesof the to tenkers sell to "C-ellirey" the Her Shipping and "Anti-Ad- ministration. I The Ihnbessy inBuenos hires has received I § information from the Greek Minister tI'Tet SUBJECT Ins j expressed sentiments inimicel to the IE1! efforts of , _ the United Nations and it is believed that his esti- vities while in the U,S, should be observed, 1 r""*§4 ;. STATE cognizant, . -

Aristotle Onassis Part 2 of 11

_ ___ ,____________._.-. ._.- .-.t--m un a _ -. ' - Q:-cnuudo. roan no 1 In-Ion i F ' on on. -Q. on. at . 1'¢,||¢,n ____._ unmao STATES MI-INT - - __ 3',§:'° --'" Bishop __._..._- Casper __.._._..__.- Calla-.m -}-- TD _ _ go=|92'nd_.--- =Mr. ne1.oa<'§§- we12-1'2-as r _ Sulllv .._--:-- ,0!!/73r T se--__._ $U|;J|5_rnom = T, E_ B1311 ". ONASSIS I[; ARISTOTL 7_ ;:i;}?°:.__:= // REQUESTwonnovvmsINFGRIviA"iIGN FEATURES, mc.FURBY / ' *- F_ - Z . - Reference is made to my memorandum of 11-27-68 in which it was noted that one Joe Trento, who said he was with Worldwide Features, called my office making inquiry regarding a letter that p Mr. Hoover had written to Admiral Land of the War Shipping Administra- tion regardingAristotle Onassis.It was noted thatTrento wasparticularly Iobnoxious prepared andsuch demandeda letter. vericationHe wasveryasfirmly advisedto whether or thatnot MI. filesFBIHoover had were confidential and that -could be of no help whatsoever to him. ' 1_' h ational E_n_qui£_e_1_'_,low-order s<_:_a_nda1 a sheet dated 12-29-68 carries a photostat of the letter from Mr. Hoover to ' Admiral Land. The article in the Enquirer claims that an FBI spokes- man confirmed that such a letter existed and confirmed that it had a n £1-sun rinnnsn-I-=u In-I AI-'u n G nnnn: nu 'I-I-u an vi uran toldluuggllis absolutelyUzlaaan.nothing. -

Olympia Prize for IUCN

62 Environmental Conservation and that there is a pressing need for additional nature 'N.A.T.' (1976). Cue Phuong National Park. Viet Nam Courier, reserves. Economic conditions, however, seem to make 12(46), pp. 26-8. NGAN, Phung Trung (1968). Status of conservation in South early action improbable in both cases. Vietnam. Pp. 519-22 in Conservation in Tropical South East Asia (Ed. L. M. Talbot & M. H. Talbot). International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, REFERENCES Morges, Switzerland, Publ. n.s. No. 10, 550 pp., illustr. NOWAK, R. M. (1976). Wildlife of Indochina: tragedy or oppor- AVRORIN, N. A. (1964). [First tropical 'botanical garden re- tunity? National Parks and Conservation Mag., 50(6), pp. serve' in North Viet Nam.—in Russian]. Botaniceskii 13-18. Zhurnal, 49, pp. 1521-23. TALBOT, L. M. (1959). A Look at Threatened Species. Fauna CONSTABLE, J. D. (in press). Wildlife in Vietnam. Oryx. Preservation Society, London, UK: 137 pp., illustr. IPPL. (1974). Conditions for primates in Vietnam. International WESTING, A. H. (1976). Ecological Consequences of the Primate Protection League Newsletter, 1(2), pp. 2-3. Second Indochina War. Almqvist & Wiksell, Stockholm, LIPPOLD, L. K. (1977). Douc Langur: A time for conservation. Sweden: x + 119 pp., illustr. Pp. 513-38 in Primate Conservation (Ed. Rainier III & WESTING, A. H. (1980). Warfare in a Fragile World: Military G. H. Bourne). Academic Press, New York, NY: xviii + Impact on the Human Environment. Taylor & Francis, 658 pp., illustr. London, UK: xiv + 249 pp. Sinai Wilderness Marred by Paint-spraying Incredible as it may sound, a French 'artist', Jean Protection of Nature, which, during Israeli occupation of Verame, has been spray-painting the mountains in the the Sinai, was a major force in establishing conservation previously unspoiled valley of Bir Nafach, an area close standards in the area. -

Hans Christian Andersen Award 2018 Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center Athens, Greece Friday, 31 August 2018

Hans Christian Andersen Award 2018 Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center Athens, Greece Friday, 31 August 2018 Welcome by Hans Christian Andersen Jury President Patricia Aldana Welcome to this beautiful building in this most magnificent city of Athens for the very special evening when the 2018 winners of the Hans Christian Andersen Award will be honoured as they deserve. I would like to welcome not only all the Congress participants, but also His Excellency Mr Yasuhiro Shimizu the Japanese Ambassador to Greece and his wife Mrs Yoshimi Shimizu and Mr Vladimir Grigoriev the Deputy Head for the Russian Federal Agency for Press and Mass Communications. I also want to take this opportunity to warmly thank Vassiliki Nika and her organizing committee for this fantastic congress and especially for this impressive venue for this Award evening. However, before I do anything else I would like to once again thank our generous and wonderful sponsors, Nami Island Inc, the Minn family and Mr Kang. I would like to invite Mrs Lee to the stage to say a few words on behalf of our generous and engaged sponsor of the most prestigious international award for children’s literature. Greetings from the sponsor Nami Island Inc. by Lee Kye Young, Vice Chairperson of Nami Island I would also like to welcome four Andersen nominees that are with us today. Please come to the stage to receive your diplomas as I call your name: Vagelis Iliopoulos, Author from Greece Jeannie Baker, Illustrator from Australia Andres Konstantinides, Author from Cyprus Farhad Hassanzedeh, Author from Iran Gundega Muzikante, Illustrator from Latvia In addition, I would like to invite the sister of Christos Dimos, the Illustrator nominee from 1 Greece, who would like to be here but cannot join us on health grounds, so I welcome Martha Dimou to receive his diploma on his behalf. -

New Round of Pandemic Relief from the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF) Provides Wide-Ranging Aid to Organizations Delivering Ke

New round of pandemic relief from the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF) provides wide-ranging aid to organizations delivering key education, food, and social services in U.S., Europe, and Africa. New round of more than $6.9 million in SNF’s $100 million global COVID-19 relief initiative brings total allocated to $88.8 million Tuesday, March 2, 2021 – As global vaccination efforts and new variants of the virus continuously shift the landscape of the pandemic, the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF) continues to focus on meeting urgent needs for vulnerable populations in a way that also lays groundwork for recovery through its $100 million global COVID-19 relief initiative. In this sixth round of grants, 32 grants total more than $6.9 million and bring the overall total allocated through the initiative so far to $88.8 million. The new grants aim to help keep kids’ education on track, combat elevated food insecurity, make quality health care accessible in remote settings, provide access to clean water, and more. “One year ago, we could not have predicted where we would find ourselves now,” said SNF Co-President Andreas Dracopoulos. “What the next months hold will be determined in large part by leadership across sectors, and these organizations demonstrate a critical type of leadership: leading by action. SNF is proud to partner with organizations trusted in their communities to help meet the needs of the most vulnerable.” As it has been since the start of the pandemic, food insecurity remains a dire and growing need, including in communities across the United States. -

Stavros Niarchos Center (Greece)

Project information Stavros Niarchos Center (Greece) Project description mageba scope Highlights & facts The Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural In order to ensure that the building struc- Center (SNFCC) in Athens is a multifunc- ture can withstand even a severe earth- mageba products: tional arts, education and recreation com- quake of the type Athens has known Type: RESTON®PENDULUM plex. It includes, within its 170,000 m2 for thousands of years, the buildings of Curved Surface Sliders park, new state-of-the-art facilities for the the National Library of Greece and the RESTON®SA shock National Library of Greece and the Greek Greek National Opera are built on 323 absorbers National Opera. RESTON®PENDULUM Curved Surface RESTON®SP elastic spring devices The buildings were designed by Renzo Pi- Sliders. The 323 seismic isolators allow ano, the internationally acclaimed archi- dynamic movements of +/- 350 mm and ROBO®CONTROL SHM tect who achieved worldwide fame in the carry loads of up to 70,000 kN per unit. Installation: 2013–2015 1970s with the Centre Georges Pompidou A solar collector roof canopy with an Structure: in Paris. With a budget of €566 million, the area of 10,000 m2 is also equipped with City: Athens SNFCC is one of the largest construction 60 RESTON®SA shock absorbers and 120 projects in recent Greek history. RESTON®SP spring devices to resist the Country: Greece strong wind forces arising. All these de- Completed: 2016 vices regulate the connections to the 30 Type: Cultural centre column heads that hold the roof, damping Owner: Stavros Niarchos all vertical vibrations. -

Israel's Air Force the Pill Is Safe

EXCLUSIVE: ISRAEL'S AIR FORCE Is it the world's best? A top medical expert says: • THE PILL IS SAFE A LOOK BONUS: PREVIEW OF DORIS LILLY'S REVEALING NEW BOOK 146'76 ti7 :,7,711A 111H a Y006 311S10 5:1101 1 A1-17 ET Z 0 Tarr '76n5E00 ilK 99620i ONCE UPON A TIME, a boy was born JACKIE -style school caps. World War I offi- in Kaysed, Turkey, and his name was cially ended in -1918, and the Onassis Socrates Onassis. family had survived it very well. Tobac- Since the fall of Constantinople, co could now be exported freely, and it the Onassis family and other Greeks seemed the road to riches had been living in Turkey had been subjects of opened. But the war was far from over the Turkish sultan. The Turks were for Smyrna. In 1919, Greek troops, great warriors, but it was the Greeks FABUL supported by Allied warships, occu- who functioned as administrators and transacted pied the city. For the next three years, Smyrna most of the business of the Turkish Empire. was Greek. Young Aristo clamped his British- Socrates could have studied at a Greek college style cap back on his jet-black hair and returned in Kayseri and then gone to work as a petty func- to the recently reopened Evangeliki Scholi. He tionary of the sultan's civil service. Instead, he joined a sporting, club and became outstanding started a small business and moved to Smyrna, at water polo. which was then an important, bustling town. More He said later that he.was in line for a place than half its population was Greek.