Styles of Secular Recovery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Controlled Drinking: More Than Just a Controversy 05/07/2007 08:37 AM

Controlled Drinking: More Than Just a Controversy 05/07/2007 08:37 AM www.medscape.com To Print: Click your browser's PRINT button. NOTE: To view the article with Web enhancements, go to: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/473554 Controlled Drinking: More Than Just a Controversy Michael E. Saladin; Elizabeth J. Santa Ana Curr Opin Psychiatry 17(3):175-187, 2004. © 2004 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Posted 04/28/2004 Abstract and Introduction Abstract Purpose of Review: We intend to provide clinicians and clinical scientists with an overview of developments in the controlled-drinking literature, primarily since 2000. A brief description of the controversy surrounding controlled drinking provides a context for a discussion of various approaches to controlled drinking intervention as well as relevant clinical research. Recent Findings: Consistent with previous research, behavioral self-control training continues to be the most empirically validated controlled-drinking intervention. Recent research has focused on increasing both the accessibility/availability and efficacy of behavioral self-control training. Moderation-oriented cue exposure is a recent development in behaviorally oriented controlled drinking that yields treatment outcomes comparable to behavioral self-control training. The relative efficacy of moderation-oriented cue exposure versus behavioral self- control training may vary depending on the format of treatment delivery (group versus individual) and level of drinking severity. In general, the efficacy of both techniques does not appear to vary as a function of drinking severity but may vary as a function of drinking-related self-efficacy. Guided-self change is a relatively new and brief cognitive-behavioral intervention that has demonstrated efficacy with problem drinkers. -

ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: 2020 Focused Update

The ASAM NATIONAL The ASAM National Practice Guideline 2020 Focused Update Guideline 2020 Focused National Practice The ASAM PRACTICE GUIDELINE For the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder 2020 Focused Update Adopted by the ASAM Board of Directors December 18, 2019. © Copyright 2020. American Society of Addiction Medicine, Inc. All rights reserved. Permission to make digital or hard copies of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for commercial, advertising or promotional purposes, and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the fi rst page. Republication, systematic reproduction, posting in electronic form on servers, redistribution to lists, or other uses of this material, require prior specifi c written permission or license from the Society. American Society of Addiction Medicine 11400 Rockville Pike, Suite 200 Rockville, MD 20852 Phone: (301) 656-3920 Fax (301) 656-3815 E-mail: [email protected] www.asam.org CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: 2020 Focused Update 2020 Focused Update Guideline Committee members Kyle Kampman, MD, Chair (alpha order): Daniel Langleben, MD Chinazo Cunningham, MD, MS, FASAM Ben Nordstrom, MD, PhD Mark J. Edlund, MD, PhD David Oslin, MD Marc Fishman, MD, DFASAM George Woody, MD Adam J. Gordon, MD, MPH, FACP, DFASAM Tricia Wright, MD, MS Hendre´e E. Jones, PhD Stephen Wyatt, DO Kyle M. Kampman, MD, FASAM, Chair 2015 ASAM Quality Improvement Council (alpha order): Daniel Langleben, MD John Femino, MD, FASAM Marjorie Meyer, MD Margaret Jarvis, MD, FASAM, Chair Sandra Springer, MD, FASAM Margaret Kotz, DO, FASAM George Woody, MD Sandrine Pirard, MD, MPH, PhD Tricia E. -

Staying Connected Is Important: Virtual Recovery Resources

STAYING CONNECTED IS IMPORTANT: VIRTUAL RECOVERY RESOURCES • Refuge Recovery: Provides online and virtual INTRODUCTION support In an infectious disease outbreak, when social https://www.refugerecovery.org/home distancing and self-quarantine are needed to • Self-Management and Recovery Training limit and control the spread of the disease, (SMART) Recovery: Offers global community continued social connectedness to maintain of mutual-support groups, forums including a recovery is critically important. Virtual chat room and message board resources can and should be used during this https://www.smartrecovery.org/community/ time. Even after a pandemic, virtual support may still exist and still be necessary. • SoberCity: Offers an online support and recovery community This tip sheet describes resources that can be https://www.soberocity.com/ used to virtually support recovery from mental/ substance use disorders as well as other • Sobergrid: Offers an online platform to help resources. anyone get sober and stay sober https://www.sobergrid.com/ • Soberistas: Provides a women-only VIRTUAL RECOVERY PROGRAMS international online recovery community https://soberistas.com/ • Alcoholics Anonymous: Offers online support • Sober Recovery: Provides an online forum for https://aa-intergroup.org/ those in recovery and their friends and family https://www.soberrecovery.com/forums/ • Cocaine Anonymous: Offers online support and services • We Connect Recovery: Provides daily online https://www.ca-online.org/ recovery groups for those with substance use and -

SMART Recovery® History

A Chronology of SMART Recovery® Compiled by Shari Allwood and William White Pre-SMART Recovery Milestones 1975 Jean Kirkpatrick, PhD, founds Women for Sobriety, the first secular alcoholism recovery alternative to Alcoholics Anonymous. 1985 Jack and Lois Trimpey found Rational Recovery (RR). Late 1980s Early 1990s Rational Recovery meetings spread in the US. 1990 Articles in the Boston Globe and the New York Times as well as television coverage on such programs as The Today Show stimulate interest in rational approaches to addiction recovery. The Globe article alone generates more than 400 calls about Rational Recovery. First RR meeting takes place at a hospital: Mount Auburn Hospital, Cambridge, MA, 1990. There are 14 RR groups meeting in the US. 1991 Jack and Lois Trimpey host the first meeting of the informal board of professional advisors to Rational Recovery in February in Dallas, Texas. A number of the individuals who will later start SMART Recovery are in attendance. 1992 Rational Recovery prison meetings start at MCI-Concord (MA) October 6, 1992, led by Barbara Gerstein, RN, and Wally White. Prof. Marc Galanter (NYU) and colleagues conduct a survey study of participants in 30 Rational Recovery groups throughout the US. They conclude that RR engages participants and the likelihood of abstinence increases with the length of participation. 1993 Survey study of Rational Recovery groups by the West End Group, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Harvard Medical School reaches the same conclusions as the 1992 Galanter group study. Rational Recovery training conference is held at Hyatt Harborside Hotel in Boston in conjunction with a scientific meeting featuring James Prochaska and Tom Miller as the main speakers. -

Sacrifice, Stigma, and Free-Riding in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA): a New Perspective on Behavior Change in Self-Help Organizations for Addiction

Sacrifice and stigma in AA Sacrifice, stigma, and free-riding in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA): A new perspective on behavior change in self-help organizations for addiction Anna Lembke, MD Stanford University February 2013 Abstract Iannaccone and others have claimed that behavior change in religious organizations is mediated in part by sacrifice and stigma, which enhances participation, augments club goods that make participation worthwhile, and reduces free-riding. As applied to Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), a non-religious self-help organization for addiction, Iannaccone’s ideas shed light on the ways in which sacrifice and stigma influence behavior in AA. AA members’ willingness to embrace a stigmatized identity, give up alcohol, and participate in the AA fellowship, creates the club goods that are integral to ‘recovery’ from addiction. Iannaccone’s model furthermore illuminates the problem of free-riding in AA, providing one explanation for the incredible rate of growth of AA over the years, particularly as compared with less ‘strict’ self-help organizations for alcohol use problems, such as Moderation Management. Keywords Sacrifice, stigma, free-riding, 12-steps, Alcoholics Anonymous, Moderation Management, mechanism of change 1 Sacrifice and stigma in AA Introduction Addictive disorders represent one of the greatest public health threats to the developed world, contributing to the suffering of millions, including over 500,000 substance-use-related U.S. deaths annually (Horgan et al., 2001). Self-help organizations are the most commonly utilized treatment for people with addiction in the United States today (Miller and McCrady, 1993). There exist many different types of self-help organizations for addiction, e.g. -

Women Recovering in Alcoholics Anonymous: the Impact of Social Bonding

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2003 Women recovering in Alcoholics Anonymous: The impact of social bonding Tina Marie Wininger University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Wininger, Tina Marie, "Women recovering in Alcoholics Anonymous: The impact of social bonding" (2003). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1570. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/s5bx-078s This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WOMEN RECOVERING IN ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS: THE IMPACT OF SOCIAL BONDING by Tina Marie Wininger Bachelor of Arts University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2000 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Sociology Department of Sociology College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas August 2003 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1417743 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Addiction : an Information Guide / Marilyn Herie

A addiction can affect your health, relationships, finances, d d i c career—every aspect of your life. You may not see your t i o substance use as a problem, and even if you do, it can still n Addiction be hard to change. A n Addiction: An Information Guide is for people who are i n f having problems with alcohol or other drugs, their families o r m and friends, and anyone else who wants to better under - a An t i o stand addiction. The guide describes what addiction is, n g what is thought to cause it, and how it can be managed u i d and treated. The guide also includes ways family members e can support people with addiction while taking care of information themselves, and tips on explaining addiction to children. guide This publication may be available in other formats. For information about alternate formats or other CAMH publications, or to place an order, please contact Sales and Distribution: Toll-free: 1 800 661-1111 Toronto: 416 595-6059 E-mail: [email protected] Online store: http://store.camh.net To make a donation, please contact the CAMH Foundation: Tel.: 416 979-6909 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.camh.net Disponible en français. Marilyn Herie, PhD, RSW 3 4 Tim Godden, MSW, RSW 0 M P Joanne Shenfeld, MSW, RSW / 0 1 0 Colleen Kelly, MSW, RSW 2 - 5 0 / d 3 A Pan American Health Organization / 7 9 World Health Organization Collaborating Centre 3 i Addiction An information guide A GUIDE FOR PEOPLE WITH ADDICTION AND THEIR FAMILIES Marilyn Herie, PhD, RSW Tim Godden, MSW, RSW Joanne Shenfeld, MSW, RSW Colleen Kelly, MSW, RSW A Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization Collaborating Centre ii Addiction: An information guide Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Addiction : an information guide / Marilyn Herie.. -

SMART Bibliography Peer Reviewed Publications and Monographs Aslan, L., Parkman, T. J., & Skagerlind, N. (2016). an Evaluati

SMART Bibliography Peer Reviewed Publications and Monographs Aslan, L., Parkman, T. J., & Skagerlind, N. (2016). An evaluation of the mutual aid facilitation sessions pilot program, you do the MAFS. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery, 11(2), 109- 124. Atkins, Jr., R. G., & Hawdon, J. E. (2007). Religiosity and participation in mutual-aid support groups for addiction. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 33(3), 321-331. Beck, A.K., Forbes, E., Baker, A., Kelly, P., Deane, F., Shakeshaft, A, Hunt, D., & Kelly, J. (2017). Systematic review of SMART Recovery: Outcomes, process variables, and implications for research. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(1), 1-20. Beck, A. K., Baker, A., Kelly, P. J., Deane, F. P., Shakeshaft, A., Hunt, D., & Kelly, J. F. (2016). Protocol for a systematic review of evaluation results for adults who have participated in ‘SMART recovery’ mutual support programme. BMJ Open, (May)6(5), e009934. Beck, A. K., Baker, A. L., Kelly, P. J., Shakeshaft, A., Deane, F. P., & Hunt, D. (2015). Exploring the evidence: A systematic review of SMART Recovery evaluations. Drug and Alcohol Review, 34, 7- Bennett, A., & Hunter, M. (2016). Implementing evidence-based psychological substance misuse interventions in a high secure prison based personality disorder treatment service. Advances in Dual Diagnosis, 9(2/3), 108-116. Best, D. (2012). Addiction recovery: A movement for social change and personal growth in the UK. Brighton: Pavilion Publishing. Best, D. W., Haslam, C., Staiger, P., Dingle, G., Savic, M., Bathish, R., . Lubman, D. I. (2016). Social networks and recovery (SONAR): characteristics of a longitudinal outcome study in five therapeutic communities in Australia. -

Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology Context and Craving Among Individuals with Alcohol Use Disorder Attempting to Moderate Their Drinking Alexis N

Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology Context and Craving Among Individuals With Alcohol Use Disorder Attempting to Moderate Their Drinking Alexis N. Kuerbis, Sijing Shao, Hayley Treloar Padovano, Anna Jadanova, Danusha Selva Kumar, Rachel Vitale, George Nitzburg, Nehal P. Vadhan, and Jon Morgenstern Online First Publication, January 23, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pha0000349 CITATION Kuerbis, A. N., Shao, S., Treloar Padovano, H., Jadanova, A., Selva Kumar, D., Vitale, R., Nitzburg, G., Vadhan, N. P., & Morgenstern, J. (2020, January 23). Context and Craving Among Individuals With Alcohol Use Disorder Attempting to Moderate Their Drinking. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pha0000349 Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology © 2020 American Psychological Association 2020, Vol. 1, No. 999, 000 ISSN: 1064-1297 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pha0000349 Context and Craving Among Individuals With Alcohol Use Disorder Attempting to Moderate Their Drinking Alexis N. Kuerbis Sijing Shao City University of New York Center for Addiction Services and Psychotherapy Research, Northwell Health, Great Neck, New York Hayley Treloar Padovano Anna Jadanova, Danusha Selva Kumar, Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, Providence, Rachel Vitale, George Nitzburg, Nehal P. Vadhan, Rhode Island and Jon Morgenstern Center for Addiction Services and Psychotherapy Research, Northwell Health, Great Neck, New York Many individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD) prefer a goal of moderation, because they do not see their drinking as causing severe enough consequences to merit abstinence. Given that individuals attempting to moderate will continue to put themselves in contexts where drinking occurs, understanding how distinct external alcohol cues prompt craving is important for implementing the optimal treatments for individuals with AUD. -

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Substance Use Disorders Among Veterans

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Substance Use Disorders Among Veterans Therapist Manual Josephine M. DeMarce, Ph.D. Maryann Gnys, Ph.D. Susan D. Raffa, Ph.D. Bradley E. Karlin, Ph.D. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Substance Use Disorders Among Veterans Therapist Manual Suggested Citation: DeMarce, J. M., Gnys, M., Raffa, S. D., & Karlin, B. E. (2014). Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Substance Use Disorders Among Veterans: Therapist Manual. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Table of Contents Table of Figures ..............................................................................................................................................vii Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................................... ix Preface ............................................................................................................................................................... x Part 1: Background, Theory, Case Conceptualization, and Treatment Structure ....................1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 What is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy? ........................................................................................................ 2 About the Manual ......................................................................................................................................... -

The SMART Recovery 4-Point Program®

CLICK & Donate to SMART Recovery ® Bringing Science and Reason to Self-help with Addictive Behaviors Volume 24, Issue 3 • July 2018 President, Joe Gerstein, M.D., FACP that SMART, LifeRing and surprising since virtually Women For Sobriety everyone in the recovery President’s Letter (WFS) provide recovery community, including support that is as effective scientists, share a common as Alcoholics Anonymous perception of recovery for people with alcohol use support groups. On the one Time to change the conversation disorders. We are thankful hand, there are AA and about SMART and recovery support to Sarah Zemore and her other 12-Step groups, and by Joe Gerstein, M.D., FACP colleagues at the Alcohol on the other, there are By many measures, Research Group for the “alternatives.” SMART is gaining long- conducting this research, sought respect and success. which tracked recovery We are endorsed by the progress among people Inside: world’s leading govern- using each group over a President’s Letter one-year period.1 ment and health Time to change the conversation about authorities focusing on The many media reports SMART and recovery support .........1 addiction. At our current on this research framed the 4-Point Program®.....................1 growth rate, the number of results in a familiar manner People Power weekly meetings will cross – that three “alternative” the 3,000 milestone this support groups are as SMART T-shirts FUNdraiser ...........3 year. Research published effective as AA – often in Call for board candidates ..............3 several -

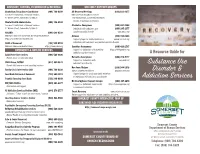

Substance Use Disorder & Addiction Services

ADVOCACY, FUNDING, INFORMATION & REFERRAL SELF-HELP SUPPORT GROUPS Alcoholism/Drug Abuse Coordinator (908) 704-6309 All Recovery Meetings (833) 233-4377 Somerset County Dept. of Human Services RWJ University Hospital Somerset 27 Warren Street, Somerville, NJ 08876 110 Rehill Avenue, Somerville, NJ 08876 Mental Health Administrator (908) 704-6302 Honors all pathways to recovery Somerset County Dept. of Human Services Alcoholics Anonymous (908) 687-8566 27 Warren Street, Somerville, NJ 08876 Individuals with substance use (800) 245-1377 NJCADD (609) 689-0599 (alcohol specific) disorder www.nnjaa.org National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence Al-Anon (973) 744-8686 https://ncaddnj.nationbuilder.com Support groups for family members of www.nj-al-anon.org NAMI of Somerset (732) 940-0991 individuals with substance use (alcohol specific) disorder National Alliance on Mental Illness https://www.nami.org Gamblers Anonymous (800) 426-2537 EMERGENCY & HOTLINE SERVICES Support for individuals with gambling https://800gambler.org addiction and their families A Resource Guide for Adult Protective Services (908) 526-8800 Report abuse of vulnerable Adult Narcotics Anonymous (844) 276-2777 Support for Individuals with www.nanj.org Child Abuse, DCP&P (877) 652-2873 substance use disorder Report child abuse or seek parenting services Substance Use Nar-Anon/Alateen (888) 944-5678 Family Crisis Intervention Unit (908) 704-6330 www.nj-al-anon.org/alateen www.nar-anon.org Food Bank Network of Somerset (732) 560-1813 Support groups for youth and family members Disorder & of individuals with substance use disorder Franklin Township Food Bank (732) 246-0009 NJ Clearinghouse Support Groups (800) 367-6274 Addiction Services HIV/AIDS Hotline (800) 624-2377 Support for individuals experiencing https://www.njgroups.org Information and support a common life situation NJ Addiction Services Hotline (IME) (844) 276-2777 Smart Recovery www.smartrecovery.org 24 hours / 7 days a week for assessment / referral Online support for substance use and gambling addiction.