Annotated Selected Bibliography & Index for Teaching African

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NGOLO: (Re)Membering the African American Child As a Normative for Self-Healing Power

NGOLO: (Re)membering the African American Child as a Normative for Self-Healing Power Patricia Nunley ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3437-8135 Abstract In response to the need to clarify the ongoing experience of historical and contemporary trauma by African American people in the USA, Dr. Wade Nobles, co-founder and past President of the ABPsi introduced the concept of ‘Psychic Terrorism’ which he defined as the systematic use of terror to immobilize and/or destabilize a person’s fundamental sense of security and safety by assaulting his or her consciousness and identity (2015: 4). The USA’s practice of psychic terrorism demands that special attention be given to African American children’s identity development. In this regard, the unconstrained, western research’s dominance continues to function as a hindrance to the understanding of Black children’s positive identity development and resultant well-being. In this context the African child’s double invisibility (Jonsson 2009; Nsamenang 2007), obscurity and under-publication, and the African American child’s double visibility, pathologies and over-publication (Jackson & Moore 2008; Kunjufu1992), inhibits an appreciation of Black children’s substantive self-identity knowledge. The consequence of this for the African Child is unrecognition of their normativity as the universal original child. For the African American child, this unrecognition also impairs their connection to their generative African essence or Ngolo. Ngolo, as defined by Fu-Kiau, means in Kikongo, the ‘energy of self-healing power’. By employing the child development discipline, this article will problematize the minimization of the African child as the norm while illuminating the critical need for African American children to function in wholeness and wellness. -

The History of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a Curriculum Tool for Afrikan American Studies

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1990 The history of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a curriculum tool for Afrikan American studies. Kit Kim Holder University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Holder, Kit Kim, "The history of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a curriculum tool for Afrikan American studies." (1990). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 4663. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/4663 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966-1972 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES A Dissertation Presented By KIT KIM HOLDER Submitted to the Graduate School of the■ University of Massachusetts in partial fulfills of the requirements for the degree of doctor of education May 1990 School of Education Copyright by Kit Kim Holder, 1990 All Rights Reserved THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966 - 1972 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES Dissertation Presented by KIT KIM HOLDER Approved as to Style and Content by ABSTRACT THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966-1971 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 1990 KIT KIM HOLDER, B.A. HAMPSHIRE COLLEGE M.S. BANK STREET SCHOOL OF EDUCATION Ed.D., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS Directed by: Professor Meyer Weinberg The Black Panther Party existed for a very short period of time, but within this period it became a central force in the Afrikan American human rights/civil rights movements. -

Afrocentric Education: What Does It Mean to Toronto’S Black Parents?

Afrocentric Education: What does it mean to Toronto’s Black parents? by Patrick Radebe M.Ed., University of Toronto, 2005 B.A. (Hons.), University of Toronto, 2000 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Educational Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) October 2017 Patrick Radebe, 2017 Abstract The miseducation of Black students attending Toronto metropolitan secondary schools, as evinced by poor grades and high dropout rates among the highest in Canada, begs the question of whether responsibility for this phenomenon lies with a public school system informed by a Eurocentric ethos. Drawing on Afrocentric Theory, this critical qualitative study examines Black parents’ perceptions of the Toronto Africentric Alternative School and Afrocentric education. Snowball sampling and ethnographic interviews, i.e., semi-structured interviews, were used to generate data. A total of 12 Black parents, three men and nine women, were interviewed over a 5-month period and data analyzed. It was found that while a majority of the respondents supported the Toronto Africentric Alternative School and Afrocentric education, some were ambivalent and others viewed the school and the education it provides as divisive and unnecessary. The research findings show that the majority of the participants were enamored with Afrocentricity, believing it to be a positive influence on Black lives. While they supported TAAS and AE, the minority, on the other hand, opposed the school and its educational model. The findings also revealed a Black community, divided between a majority seeking to preserve whatever remained of (their) African identity and a determined minority that viewed assimilation to be in the best interests of Black students. -

Volume CXXXIV, Number 21, April 28, 2017

The Student Newspaper of Lawrence University Since 1884 THELAWRENTIAN VOL. CXXXIV NO. 21 APPLETON, WISCONSIN APRIL 28, 2017 Earth Day celebrations encourage sustainability 4 p.m. on Friday, April 21. The Rikke Sponheim March for Science took place on For The Lawrentian Saturday, April 22 from 3 p.m. to 5 _______________________ p.m. in downtown Appleton. To promote environmental The closing event of the week activism, Greenfire hosted Earth was Earthfest, which was held on Week from April 17-22. The week the Main Hall Green from 1 p.m. featured various activities. Some to 4 p.m. on Sunday. There was were designed to promote enjoy- live music from several groups ing nature, but most events during and local musician Nicholas the the week focused on activism and Transparent. There were tables raising awareness for environ- organized by the Lawrence mental causes. University Gardening Society On Monday, April 17 from (LUGS), Sustainable Lawrence 6:30 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. in the Warch University Garden (SLUG), Bird Campus Center Cinema, Barbara and Nature Club, Lawrence Royal, a veterinarian based in University Women in Science Illinois, gave a presentation called and Greenfire, with activities that “Life’s a Zoo and I’m Your Vet: included flower and herb planting, Wild Health Starts with Wild rock painting and bike repairs, Education” and Matthew Gies, an Food was also provided. organic farmer, presented “From “[Earth Week is] an impor- Chicago Peregrine Falcons to tant reminder that, although Michigan Organic Hops Farming: everyday should be Earth Day, It’s Not As Far As You’d Think.” we often don’t treat it as such,” Both spoke about their occu- said Pike. -

50Th Anniversary of the Assassination of Illinois Black Panther Chairman Fred Hampton with Dr

50th Anniversary of the Assassination of Illinois Black Panther Chairman Fred Hampton with Dr. Jakobi Williams: library resources to accompany programs FROM THE BULLET TO THE BALLOT: THE ILLINOIS CHAPTER OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY AND RACIAL COALITION POLITICS IN CHICAGO. IN CHICAGO by Jakobi Williams: print and e-book copies are on order for ISU from review in Choice: Chicago has long been the proving ground for ethnic and racial political coalition building. In the 1910s-20s, the city experienced substantial black immigration but became in the process the most residentially segregated of all major US cities. During the civil rights struggles of the 1960s, long-simmering frustration and anger led many lower-class blacks to the culturally attractive, militant Black Panther Party. Thus, long before Jesse Jackson's Rainbow Coalition, made famous in the 1980s, or Barack Obama's historic presidential campaigns more recently, the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party (ILPBB) laid much of the groundwork for nontraditional grassroots political activism. The principal architect was a charismatic, marginally educated 20-year-old named Fred Hampton, tragically and brutally murdered by the Chicago police in December 1969 as part of an FBI- backed counter-intelligence program against what it considered subversive political groups. Among other things, Williams (Kentucky) "demonstrates how the ILPBB's community organizing methods and revolutionary self-defense ideology significantly influenced Chicago's machine politics, grassroots organizing, racial coalitions, and political behavior." Williams incorporates previously sealed secret Chicago police files and numerous oral histories. Other review excerpts [Amazon]: A fascinating work that everyone interested in the Black Panther party or racism in Chicago should read.-- Journal of American History A vital historical intervention in African American history, urban and local histories, and Black Power studies. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. April 22, 2019 to Sun. April 28, 2019 Monday

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. April 22, 2019 to Sun. April 28, 2019 Monday April 22, 2019 4:00 PM ET / 1:00 PM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT Rock Legends Smart Travels Europe Amy Winehouse - Despite living a tragically short life, Amy had a significant impact on the music Out of Rome - We leave the eternal city behind by way of the famous Apian Way to explore the industry and is a recognized name around the world. Her unique voice and fusion of styles left a environs of Rome. First it’s the majesty of Emperor Hadrian’s villa and lakes of the Alban Hills. musical legacy that will live long in the memory of everyone her music has touched. Next, it’s south to the ancient seaport of Ostia, Rome’s Pompeii. Along the way we sample olive oil, stop at the ancient’s favorite beach and visit a medieval hilltop town. Our own five star villa 4:30 PM ET / 1:30 PM PT is a retreat fit for an emperor. CMA Fest Thomas Rhett and Kelsea Ballerini host as more than 20 of your favorite artists perform their 6:30 AM ET / 3:30 AM PT newest hits, including Carrie Underwood, Blake Shelton, Keith Urban, Jason Aldean, Luke Bryan, Rock Legends Dierks Bentley, Thomas Rhett, Chris Stapleton, Kelsea Ballerini, Jake Owen, Darius Rucker, Broth- Pearl Jam - Rock Legends Pearl Jam tells the story of one of the world’s biggest bands, featuring ers Osborne, Lauren Alaina and more. insights from music critics and showcasing classic music videos. -

The Case Against Afrocentrism. by Tunde Adeleke

50 The Case Against Afrocentrism. By Tunde Adeleke. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009. 224 pp. Since the loosening of Europe’s visible political and social clutch on the continent of Africa, conversations underlining common experiences and links between Black Africans and Blacks throughout the Diaspora have amplified and found merit in the Black intellectual community. Afrocentrist, such as Molefi Asante, Marimba Ani, and Maulana Karenga, have used Africa as a source of all Black identity, formulating a monolithic, essentialist worldview that underscores existing fundamentally shared values and suggests a unification of all Blacks under one shared ideology for racial uplift and advancement. In the past decade, however, counterarguments for such a construction have found their way into current discourses, challenging the idea of a worldwide, mutual Black experience that is foundational to Afrocentric thought. In The Case Against Afrocentrism, Tunde Adeleke engages in a deconstruction and reconceptualization of the various significant paradigms that have shaped the Afrocentric essentialist perspective. Adeleke’s text has obvious emphasis on the difficulty of utilizing Africa in the construction of Black American identity. A clear supporter of the more “realistic” Du Boisian concept of double-consciousness in the Black American experience, Adeleke challenges Afrocentrists’, mainly Molefi Asante’s, rejection of the existence of American identity within a Black body. He argues against the “flawed” perception that Black Americans remain essentially African despite centuries of separation in slavery. According to Adeleke, to suggest that Blacks retain distinct Africanisms undermines the brutality and calculating essence of the slave system that served as a process of “unmasking and remaking of a people’s consciousness of self” (32). -

Martin Luther King Jr., Cesar Chavez, and the Images of Their Movements

MIXED UP IN THE MAKING: MARTIN LUTHER KING JR., CESAR CHAVEZ, AND THE IMAGES OF THEIR MOVEMENTS A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by ANDREA SHAN JOHNSON Dr. Robert Weems, Jr., Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2006 © Copyright by Andrea Shan Johnson 2006 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled MIXED UP IN THE MAKING: MARTIN LUTHER KING JR., CESAR CHAVEZ AND THE IMAGES OF THEIR MOVEMENTS Presented by Andrea Shan Johnson A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of History And hereby certify that in their opinion it is worthy of acceptance. __________________________________________________________ Professor Robert Weems, Jr. __________________________________________________________ Professor Catherine Rymph __________________________________________________________ Professor Jeffery Pasley __________________________________________________________ Professor Abdullahi Ibrahim ___________________________________________________________ Professor Peggy Placier ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe thanks to many people for helping me in the completion of this dissertation. Thanks go first to my advisor, Dr. Robert Weems, Jr. of the History Department of the University of Missouri- Columbia, for his advice and guidance. I also owe thanks to the rest of my committee, Dr. Catherine Rymph, Dr. Jeff Pasley, Dr. Abdullahi Ibrahim, and Dr. Peggy Placier. Similarly, I am grateful for my Master’s thesis committee at Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis, Dr. Annie Gilbert Coleman, Dr. Nancy Robertson, and Dr. Michael Snodgrass, who suggested that I might undertake this project. I would also like to thank the staff at several institutions where I completed research. -

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. October 15, 2018 to Sun. October 21, 2018

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. October 15, 2018 to Sun. October 21, 2018 Monday October 15, 2018 7:00 PM ET / 4:00 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT John Mayer With Special Guest Buddy Guy The Big Interview John Mayer’s soulful lyrics, convincing vocals, and guitar virtuosity have gained him worldwide Dwight Yoakam - Country music trailblazer takes time from his latest tour to discuss his career fans and Grammy Awards. John serenades the audience with hits like “Neon”, “Daughters” and and how he made it big in the business far from Nashville. “Your Body is a Wonderland”. Buddy Guy joins him in this special performance for the classic “Feels Like Rain”. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT The Big Interview 9:00 PM ET / 6:00 PM PT Emmylou Harris - Spend an hour with Emmylou Harris, as Dan Rather did, and you’ll see why she The Life & Songs of Emmylou Harris: An All-Star Concert Celebration is a legend in music. Shot in January 2015, this concert features performances by Emmylou Harris, Alison Krauss, Conor Oberst, Daniel Lanois, Iron & Wine, Kris Kristofferson, Lucinda Williams, Martina McBride, 10:00 AM ET / 7:00 AM PT Mary Chapin Carpenter, Mavis Staples, Patty Griffin, Rodney Crowell, Sara Watkins, Shawn The Life & Songs of Emmylou Harris: An All-Star Concert Celebration Colvin, Sheryl Crow, Shovels & Rope, Steve Earle, The Milk Carton Kids, Trampled By Turtles, Vince Shot in January 2015, this concert features performances by Emmylou Harris, Alison Krauss, Gill, and Buddy Miller. Conor Oberst, Daniel Lanois, Iron & Wine, Kris Kristofferson, Lucinda Williams, Martina McBride, Mary Chapin Carpenter, Mavis Staples, Patty Griffin, Rodney Crowell, Sara Watkins, Shawn 11:00 PM ET / 8:00 PM PT Colvin, Sheryl Crow, Shovels & Rope, Steve Earle, The Milk Carton Kids, Trampled By Turtles, Vince Rock Legends Gill, and Buddy Miller. -

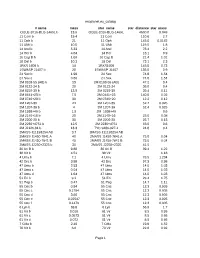

Exoplanet.Eu Catalog Page 1 # Name Mass Star Name

exoplanet.eu_catalog # name mass star_name star_distance star_mass OGLE-2016-BLG-1469L b 13.6 OGLE-2016-BLG-1469L 4500.0 0.048 11 Com b 19.4 11 Com 110.6 2.7 11 Oph b 21 11 Oph 145.0 0.0162 11 UMi b 10.5 11 UMi 119.5 1.8 14 And b 5.33 14 And 76.4 2.2 14 Her b 4.64 14 Her 18.1 0.9 16 Cyg B b 1.68 16 Cyg B 21.4 1.01 18 Del b 10.3 18 Del 73.1 2.3 1RXS 1609 b 14 1RXS1609 145.0 0.73 1SWASP J1407 b 20 1SWASP J1407 133.0 0.9 24 Sex b 1.99 24 Sex 74.8 1.54 24 Sex c 0.86 24 Sex 74.8 1.54 2M 0103-55 (AB) b 13 2M 0103-55 (AB) 47.2 0.4 2M 0122-24 b 20 2M 0122-24 36.0 0.4 2M 0219-39 b 13.9 2M 0219-39 39.4 0.11 2M 0441+23 b 7.5 2M 0441+23 140.0 0.02 2M 0746+20 b 30 2M 0746+20 12.2 0.12 2M 1207-39 24 2M 1207-39 52.4 0.025 2M 1207-39 b 4 2M 1207-39 52.4 0.025 2M 1938+46 b 1.9 2M 1938+46 0.6 2M 2140+16 b 20 2M 2140+16 25.0 0.08 2M 2206-20 b 30 2M 2206-20 26.7 0.13 2M 2236+4751 b 12.5 2M 2236+4751 63.0 0.6 2M J2126-81 b 13.3 TYC 9486-927-1 24.8 0.4 2MASS J11193254 AB 3.7 2MASS J11193254 AB 2MASS J1450-7841 A 40 2MASS J1450-7841 A 75.0 0.04 2MASS J1450-7841 B 40 2MASS J1450-7841 B 75.0 0.04 2MASS J2250+2325 b 30 2MASS J2250+2325 41.5 30 Ari B b 9.88 30 Ari B 39.4 1.22 38 Vir b 4.51 38 Vir 1.18 4 Uma b 7.1 4 Uma 78.5 1.234 42 Dra b 3.88 42 Dra 97.3 0.98 47 Uma b 2.53 47 Uma 14.0 1.03 47 Uma c 0.54 47 Uma 14.0 1.03 47 Uma d 1.64 47 Uma 14.0 1.03 51 Eri b 9.1 51 Eri 29.4 1.75 51 Peg b 0.47 51 Peg 14.7 1.11 55 Cnc b 0.84 55 Cnc 12.3 0.905 55 Cnc c 0.1784 55 Cnc 12.3 0.905 55 Cnc d 3.86 55 Cnc 12.3 0.905 55 Cnc e 0.02547 55 Cnc 12.3 0.905 55 Cnc f 0.1479 55 -

The Place of Art in Black Panther Party Revolutionary Thought and Practice: from Revolution to Reform, a Content Analysis

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-2018 The Place of Art in Black Panther Party Revolutionary Thought and Practice: From Revolution to Reform, A Content Analysis Michael James Macaluso Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Macaluso, Michael James, "The Place of Art in Black Panther Party Revolutionary Thought and Practice: From Revolution to Reform, A Content Analysis" (2018). Dissertations. 3364. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/3364 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PLACE OF ART IN BLACK PANTHER PARTY REVOLUTIONARY THOUGHT AND PRACTICE: FROM REVOLUTION TO REFORM, A CONTENT ANALYSIS by Michael Macaluso A dissertation submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sociology Western Michigan University December 2018 Doctoral Committee: Zoann Snyder, Ph.D., Chair Thomas VanValey, Ph.D. Richard Yidana, Ph.D. Douglas Davidson, Ph.D. Copyright by Michael Macaluso 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to thank Dr. Zoann Snyder, Dr. Richard Yidana, Dr. Thomas Lee VanValey, and Dr. Douglas Davidson for agreeing to serve on this committee. Zoann, I want thank you for your patience throughout this journey, I truly appreciate your assistance. Richard, your help with this work has been a significant influence to this study. -

Excerpts from Dusk of Dawn: an Essay Toward an Autobiography Of

DUSK OF DAWN An Essay Toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept W. E. B. Du Bois Series Editor, Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Introduction by K. Anthony Appiah OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Contents SERIES INTRODUCTION: THE BLACK LETTERS ON THE SIGN xi INTRODUCTION xxv APOLOGY xxxiii I. THEPLOT 1 II. A NEW ENGLAND BOY AND RECONSTRUCTION 4 III. EDUCATION IN THE LAST DECADES OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY 13 IV. SCIENCE AND EMPIRE 26 V. THE CONCEPT OF RACE 49 VI. THE WHITE WORLD 68 VII. THE COLORED WORLD WITHIN 88 VIII. PROPAGANDA AND WORLD WAR 111 IX. REVOLUTION 134 INDEX 163 WILLIAM EDWARD BURGHARDT DUBOIS: A CHRONOLOGY 171 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 179 ix CHAPTER VII The Colored World Within Not only do white men but also colored men forget the facts of the Negro's dou ble environment. The Negro American has for his environment not only the white surrounding world, but also, and touching him usually much more nearly and compellingly, is the environment furnished by his own colored group. There are exceptions, of course, but this is the rule. The American Negro, therefore, is surrounded and conditioned by the concept which he has of white people and he is treated in accordance with the concept they have of him. On the other hand, so far as his own people are concerned, he is in direct contact with individuals and facts. He fits into this environment more or less willingly. It gives him a social world and mental peace. On the other hand and especially if in education and ambition and income he is above the average culture of his group, he is often resentful of its environilcg power; partly because he does not recognize its power and partly because he is determined to consider himself part of the white group from which, in fact, he is excluded.