The Changing Relationship Between ENSO and Its Extratropical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report COOPERATIVE INSTITUTE for RESEARCH in ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES

2015 Annual Report COOPERATIVE INSTITUTE FOR RESEARCH IN ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES COOPERATIVE INSTITUTE FOR RESEARCH IN ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES 2015 annual report University of Colorado Boulder UCB 216 Boulder, CO 80309-0216 COOPERATIVE INSTITUTE FOR RESEARCH IN ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES University of Colorado Boulder 216 UCB Boulder, CO 80309-0216 303-492-1143 [email protected] http://cires.colorado.edu CIRES Director Waleed Abdalati Annual Report Staff Katy Human, Director of Communications, Editor Susan Lynds and Karin Vergoth, Editing Robin L. Strelow, Designer Agreement No. NA12OAR4320137 Cover photo: Mt. Cook in the Southern Alps, West Coast of New Zealand’s South Island Birgit Hassler, CIRES/NOAA table of contents Executive summary & research highlights 2 project reports 82 From the Director 2 Air Quality in a Changing Climate 83 CIRES: Science in Service to Society 3 Climate Forcing, Feedbacks, and Analysis 86 This is CIRES 6 Earth System Dynamics, Variability, and Change 94 Organization 7 Management and Exploitation of Geophysical Data 105 Council of Fellows 8 Regional Sciences and Applications 115 Governance 9 Scientific Outreach and Education 117 Finance 10 Space Weather Understanding and Prediction 120 Active NOAA Awards 11 Stratospheric Processes and Trends 124 Systems and Prediction Models Development 129 People & Programs 14 CIRES Starts with People 14 Appendices 136 Fellows 15 Table of Contents 136 CIRES Centers 50 Publications by the Numbers 136 Center for Limnology 50 Publications 137 Center for Science and Technology -

Diffuse Spectral Reflectance-Derived Pliocene and Pleistocene Periodicity from Weddell Sea, Antarctica Sediment Cores

Wesleyan University The Honors College Diffuse Spectral Reflectance-derived Pliocene and Pleistocene Periodicity from Weddell Sea, Antarctica Sediment Cores by Tavo Tomás True-Alcalá Class of 2015 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in Earth and Environmental Sciences Middletown, Connecticut April, 2015 Table of Contents List of Figures------------------------------------------------------------------------------IV Abstract----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------V Acknowledgements-----------------------------------------------------------------------VI 1. Introduction------------------------------------------------------------------------------1 1.1. Project Context-------------------------------------------------------------------------1 1.2. Antarctic Glacial History-------------------------------------------------------------5 1.3. Pliocene--------------------------------------------------------------------------------11 1.4. Pleistocene-----------------------------------------------------------------------------13 1.5. Weddell Sea---------------------------------------------------------------------------14 1.6. Site & Cores---------------------------------------------------------------------------19 1.7. Project Goals-------------------------------------------------------------------------22 2. Methodology----------------------------------------------------------------------------23 -

How Significant Was the 1877/78 El Niño?

1JUNE 2020 H U A N G E T A L . 4853 How Significant Was the 1877/78 El Niño? BOYIN HUANG NOAA/National Centers for Environmental Information, Asheville, North Carolina MICHELLE L’HEUREUX AND ZENG-ZHEN HU NOAA/Climate Prediction Center, College Park, Maryland XUNGANG YIN Riverside Technology, Inc. (government contractor for NOAA/NCEI), Asheville, North Carolina HUAI-MIN ZHANG NOAA/National Centers for Environmental Information, Asheville, North Carolina (Manuscript received 27 August 2019, in final form 29 February 2020) ABSTRACT Previous research has shown that the 1877/78 El Niño resulted in great famine events around the world. However, the strength and statistical significance of this El Niño event have not been fully addressed, largely due to the lack of data. We take a closer look at the data using an ensemble analysis of the Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature version 5 (ERSSTv5). The ERSSTv5 standard run indicates a strong El Niño event with a peak monthly value of the Niño-3 index of 3.58C during 1877/78, stronger than those during 1982/83, 1997/98, and 2015/16. However, an analysis of the ERSSTv5 ensemble runs indicates that the strength and significance (uncertainty estimates) depend on the construction of the ensembles. A 1000- member ensemble analysis shows that the ensemble mean Niño-3 index has a much weaker peak of 1.88C, and its uncertainty is much larger during 1877/78 (2.88C) than during 1982/83 (0.38C), 1997/98 (0.28C), and 2015/16 (0.18C). Further, the large uncertainty during 1877/78 is associated with selections of a short (1 month) period of raw-data filter and a large (20%) acceptance criterion of empirical orthogonal teleconnection modes in the ERSSTv5 reconstruction. -

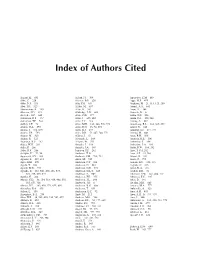

Index of Authors Cited

Index of Authors Cited Aagard, K. 641 Alford, J.J. 308 Apostolov, E.M. 665 Abbe, C. 226 Alissow, B.P. 226 Apps, M.J. 459 Abbs, D.J. 153 Aliu, Y.O. 164 Arakawa, H. 21, 114, 125, 260 Aber, J.D. 523 Allaby, M. 657 Arendt, A.A. 643 Abercromby, R. 703 Allan, R. 587 Arens, E. 164 Aberson, S.D. 243 Alldredge, L.R. 699 Arimoto, R. 6 Acevedo, O.C. 685 Allen, C.D. 177 Arkin, G.F. 804 Ackerman, B.S. 777 Allen, J. 625, 665 Arkin, P.A. 120, 266 Ackerman, T.P. 794 Allen, J.C. 318 Arking, A. 667 Ackley, S.F. 52 Allen, M.R. 163, 266, 546, 552 Armstrong, R.L. 662, 663, 804 Adams, G.A. 390 Allen, R.G. 16, 94, 373 Arnell, N. 242 Adams, J. 571, 679 Allen, R.J. 153 Arnfield, A.J. 177, 777 Adams, J.B. 793 Alley, R.B. 53, 427, 546, 571 Arnold, M. 643 Adams, M. 323 Allison, I. 54 Aron, R.H. 500 Adams, R. 323 Alvarado, L. 188 Aronson, R.B. 306 Adamson, R.S. 787 Alvarez, W. 793 Arrhenius, S. 508 Adger, W.N. 269 Amador, J. 188 Arrhenius, S.A. 460 Adler, P. 266 Amador, J.A. 189 Arritt, R.W. 164, 242 Adler, R.F. 266 Jamason, P.F. 242 Arya, S. Pal, 282 Adolphs, U. 52, 54 Ambrizzi, T 53 Arya, S.P. 31, 761 Agaponov, S.V. 699 Ambrose, S.H. 793, 794 Asami, O. 164 Agassiz, L. 387, 412 Ames, M. 740 Asaro, F. -

Sensitivity to Resolution and Topography

1DECEMBER 2019 V A R U O L O - C L A R K E E T A L . 8355 Characterizing the North American Monsoon in the Community Atmosphere Model: Sensitivity to Resolution and Topography ARIANNA M. VARUOLO-CLARKE School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Stony Brook University, State University of New York, Stony Brook, and Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, and Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Columbia University, New York, New York KEVIN A. REED Downloaded from http://journals.ametsoc.org/jcli/article-pdf/32/23/8355/4940054/jcli-d-18-0567_1.pdf by guest on 27 July 2020 School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Stony Brook University, State University of New York, Stony Brook, New York BRIAN MEDEIROS National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, Colorado (Manuscript received 29 August 2018, in final form 25 August 2019) ABSTRACT This work examines the effect of horizontal resolution and topography on the North American monsoon (NAM) in experiments with an atmospheric general circulation model. Observations are used to evaluate the fidelity of the representation of the monsoon in simulations from the Community Atmosphere Model version 5 (CAM5) with a standard 1.08 grid spacing and a high-resolution 0.258 grid spacing. The simulated monsoon has some realistic features, but both configurations also show precipitation biases. The default 1.08 grid spacing configuration simulates a monsoon with an annual cycle and intensity of precipitation within the observational range, but the monsoon begins and ends too gradually and does not reach far enough north. This study shows that the improved representation of topography in the high-resolution (0.258 grid spacing) configuration improves the regional circulation and therefore some aspects of the simulated monsoon com- pared to the 1.08 counterpart. -

Seasonal Climatology and Dynamical Mechanisms of Rainfall in the Caribbean

Climate Dynamics (2019) 53:825–846 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-019-04616-4 Seasonal climatology and dynamical mechanisms of rainfall in the Caribbean Carlos Martinez1,2 · Lisa Goddard2 · Yochanan Kushnir1 · Mingfang Ting1 Received: 22 October 2018 / Accepted: 4 January 2019 / Published online: 14 January 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract The Caribbean is a complex region that heavily relies on its rainfall cycle for its economic and societal needs. This makes the Caribbean especially susceptible to hydro-meteorological disasters (i.e. droughts and floods). Previous studies have investigated the seasonal cycle of rainfall in the Caribbean with monthly or longer resolutions that often mask the seasonal transitions and regional differences of rainfall. This has resulted in inconsistent findings on the seasonal cycle. In addition, the mechanisms that shape the climatological rainfall cycle in the region are not fully understood. To address these problems, this study conducts: (i) a principal component analysis of the annual cycle of precipitation across 38 Caribbean stations using daily observed precipitation data; and, (ii) a moisture budget analysis for the Caribbean, using the ERA-Interim Reanalysis. This study finds that the seasonal cycle of rainfall in the Caribbean hinges on three main facilitators of moisture convergence: the Eastern Pacific ITCZ, the Atlantic ITCZ, and the western flank of the North Atlantic Subtropical High (NASH). The Atlantic Warm Pool and Caribbean Low-Level Jet modify the extent of moisture provided by these main facilitators. The expansion and contraction of the western flank of NASH generate the bimodal pattern of the precipitation annual cycle in the northwestern Caribbean, central Caribbean, and with the Eastern Pacific ITCZ the western Caribbean. -

Changes and Variability in Centres of Action of the Atmosphere in the Northern Hemisphere in January and July

IGU Regional Conference, Kraków, Poland 18-22 August 2014 IGU 2014 Book of Abstracts IGU2014 – 1175 Changes and variability in centres of action of the atmosphere in the Northern Hemisphere in January and July Falarz M. Department of Climatology, Faculty of Earth Sciences, University of Silesia There were analysed long-term changes and variability of centres of action of the atmosphere (CAA) in the Northern Hemisphere in January and July in the second half of the 20th century. The geographical coordinates, baric extent and the atmospheric pressure value in the centre of each baric system (Icelandic Low (IL), Azores High (AH), Siberian High (SH), North American High (NAH), Aleutian Low (AL) and Hawaii High (HH) in January, IL, AH, Siberian Low (SL), HH in July) were read in maps of mean monthly sea level pressure basing on gridded 2,5°x 2,5 data of Reanalysis Project of the National Centre for Atmospheric Research for the period 1948-2003. The baric extent of the CAA was defined as the absolute value of the difference between the sea level pressure value in the centre of baric system and the value of pressure of the last closed isobar not including the other CAA. There were investigated trends of each CAA features and these of differences of sea level pressure values in the centres of AH and IL (D1), SH or SL and AH (D2), SH or SL and IL (D3), AH and HH (D4), HH and AL (D5), IL and AL (D6). Moreover indices of location changing of CAA centres in 4 directions (E-W/W-E, N-S/S-N, SW-NE/NE-SW, NW-SE/SE-NW) were created and analysed in the investigated period. -

Permian Paleoclimate Data from Fluid Inclusions in Halite

Chemical Geology 154Ž. 1999 113±132 Permian paleoclimate data from fluid inclusions in halite Kathleen Counter Benison a,b,), Robert H. Goldstein a a The Department of Geology, The UniÕersity of Kansas, Lawrence, USA b The Kansas Geological SurÕey, Lawrence, KS, USA Abstract This study has yielded surface water paleotemperatures from primary fluid inclusions in mid Permian Nippewalla Group halite from western Kansas. A `cooling nucleation' method is used to generate vapor bubbles in originally all-liquid primary inclusions. Then, surface water paleotemperatures are obtained by measuring temperatures of homogenization to liquid. Homogenization temperatures ranged from 218Cto508C and are consistent along individual fluid inclusion assemblages, indicating that the fluid inclusions have not been altered by thermal reequilibration. Homogenization temperatures show a range of up to 268C from base to top of individual cloudy chevron growth bands. Petrographic and fluid inclusion evidence indicate that no significant pressure correction is needed for the homogenization temperature data. We interpret these homogenization temperatures to represent shallow surface water paleotemperatures. The range in temperatures from base to top of single chevron bands may reflect daily temperatures variations. These Permian surface water temperatures fall within the same range as some modern evaporative surface waters, suggesting that this Permian environment may have been relatively similar to its modern counterparts. Shallow surface water temperatures in evaporative settings correspond closely to local air temperatures. Therefore, the Permian surface water temperatures determined in this study may be considered proxies for local Permian air temperatures. q 1999 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Lacustrine sediments; Evaporites; Nonmarine; Nippewalla group; Homogenization temperatures 1. -

Late Quaternary Changes in Climate

SE9900016 Tecnmcai neport TR-98-13 Late Quaternary changes in climate Karin Holmgren and Wibjorn Karien Department of Physical Geography Stockholm University December 1998 Svensk Kambranslehantering AB Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Co Box 5864 SE-102 40 Stockholm Sweden Tel 08-459 84 00 +46 8 459 84 00 Fax 08-661 57 19 +46 8 661 57 19 30- 07 Late Quaternary changes in climate Karin Holmgren and Wibjorn Karlen Department of Physical Geography, Stockholm University December 1998 Keywords: Pleistocene, Holocene, climate change, glaciation, inter-glacial, rapid fluctuations, synchrony, forcing factor, feed-back. This report concerns a study which was conducted for SKB. The conclusions and viewpoints presented in the report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily coincide with those of the client. Information on SKB technical reports fromi 977-1978 {TR 121), 1979 (TR 79-28), 1980 (TR 80-26), 1981 (TR81-17), 1982 (TR 82-28), 1983 (TR 83-77), 1984 (TR 85-01), 1985 (TR 85-20), 1986 (TR 86-31), 1987 (TR 87-33), 1988 (TR 88-32), 1989 (TR 89-40), 1990 (TR 90-46), 1991 (TR 91-64), 1992 (TR 92-46), 1993 (TR 93-34), 1994 (TR 94-33), 1995 (TR 95-37) and 1996 (TR 96-25) is available through SKB. Abstract This review concerns the Quaternary climate (last two million years) with an emphasis on the last 200 000 years. The present state of art in this field is described and evaluated. The review builds on a thorough examination of classic and recent literature (up to October 1998) comprising more than 200 scientific papers. -

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript and are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was scanned as received. 61,81 , & 82 This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE INTRASEASONAL VARIABILITY OF THE NORTH AMERICAN MONSOON OVER ARIZONA A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Pamela Lynn Heinselman Norman, Oklahoma 2004 UMI Number: 3117196 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3117196 Copyright 2004 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 © Copyright by Pamela Lynn Heinselman 2004 All Rights Reserved INTRASEASONAL VARIABILITY IN THE NORTH AMERICAN MONSOON OVER ARIZONA A Dissertation APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF METEOROLOGY BY Dr. Frederick Carr . ^ r. David Sch Dr. Michael Richman D^. Alan Sfiapiro . David S î^s fu d /I Dr. May Yuan Acknowledgments This dissertation arose from personal perseverance and support and encouragement from my Ph.D. -

Atlantic Multi-Decadal Oscillation and Changes of Summer Air Temperature in Montenegro

Doderovic, M. M., et al.: Atlantic Multi-Decadal Oscilation and Changes ... THERMAL SCIENCE: Year 2015, Vol. 19, Suppl. 2, pp. S405-S414 S405 ATLANTIC MULTI-DECADAL OSCILLATION AND CHANGES OF SUMMER AIR TEMPERATURE IN MONTENEGRO by * Miroslav M. DODEROVIC a and Dragan B. BURIC b a Faculty of Philosophy, University of Montenegro, Niksic, Montenegro b Hydrometeorological Institute of Montenegro, Podgorica, Montenegro Original scientific paper DOI: 10.2298/TSCI150430115D The paper has examined the impact of variations of Atlantic multidecadal oscilla- tion on the change in air temperature during the summer season on the territory of Montenegro. Starting from the fact that in recent years more and more extreme weather events occur, as well as from the intention to comprehensively consider the temperature conditions in the territory of Montenegro, first analysis is of changes in air temperature in 8 parameters, of which 5 climate indices; connections with At- lantic multidecadal oscillation have also been analyzed. To study changes in tem- perature extreme indexes proposed by the WMO CCL/CLIVAR are used. Research within the listed topics was realized using data from 23 meteorological stations for the period 1951-2010 and the calculations are done for the summer season. The re- sults show that there is increased number of maximum and minimum daily tempera- tures of warmer value. The impact assessment Atlantic multidecadal oscillation, teleconnection pattern that is quite distant, showed that its variability affects changes in summer temperatures in Montenegro, both in terms of mean values, and the frequency of extreme actions presented by climate indices. Key words: temperature, extremes, the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation, Montenegro. -

Drought Impacts in the Southern Regionoffice of Sustainability & Climate

United States Department of Agriculture Drought Impacts in the Southern RegionOffice of Sustainability & Climate A synopsis of presentations and ideas from the Drought Adaptation Workshop in Region 8 January 2017 Atlanta, GA Forest Service Washington Office February 2018 Office of Sustainability and Climate Office of Sustainability & Climate Drought Impacts Office of Sustainability & Climate in the Southern Region Background In January 2017, the USDA Forest Service hosted a two-day drought adaptation workshop in Atlanta, Georgia to share state-of-science information on drought and climate effects in the region and to develop management response strategies. The workshop was attended by regional experts Arno Photography/Shutterstock © Phillip from the Forest Service Southern Region, Southern According to the National Drought Mitigation Research Station, and Office of Sustainability and Climate; the USDA Southeast Regional Climate Hub; Center, drought originates from an and state and federal climate offices. They met to insufficiency of precipitation over an extended address challenges, cultivate opportunities, and time period—usually more than a season— develop and expand the collective understanding producing a water shortage for some activity, of the most effective management strategies to group, or environmental sector. Types of adapt to and mitigate the effects of drought in the drought include: region. The workshop focused on the effects of, » Meteorological – degree of dryness in and management responses to, drought in forest, weather over a defined period of time; riparian, and aquatic ecosystems. » Agricultural – links meteorological drought Drought in the Southern Region with agricultural impacts; » Hydrological – precipitation deficits, with Although the southeastern United States is emphasis on effects on the hydrological frequently impacted by hurricanes and floods, system (e.g., water storage and flux); and drought conditions are also relatively common.