Psychological Realism in Modern Animation: Greater Unities of Form and Content

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memetic Proliferation and Fan Participation in the Simpsons

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL Craptacular Science and the Worst Audience Ever: Memetic Proliferation and Fan Participation in The Simpsons being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of PhD Film Studies in the University of Hull by Jemma Diane Gilboy, BFA, BA (Hons) (University of Regina), MScRes (University of Edinburgh) April 2016 Craptacular Science and the Worst Audience Ever: Memetic Proliferation and Fan Participation in The Simpsons by Jemma D. Gilboy University of Hull 201108684 Abstract (Thesis Summary) The objective of this thesis is to establish meme theory as an analytical paradigm within the fields of screen and fan studies. Meme theory is an emerging framework founded upon the broad concept of a “meme”, a unit of culture that, if successful, proliferates among a given group of people. Created as a cultural analogue to genetics, memetics has developed into a cultural theory and, as the concept of memes is increasingly applied to online behaviours and activities, its relevance to the area of media studies materialises. The landscapes of media production and spectatorship are in constant fluctuation in response to rapid technological progress. The internet provides global citizens with unprecedented access to media texts (and their producers), information, and other individuals and collectives who share similar knowledge and interests. The unprecedented speed with (and extent to) which information and media content spread among individuals and communities warrants the consideration of a modern analytical paradigm that can accommodate and keep up with developments. Meme theory fills this gap as it is compatible with existing frameworks and offers researchers a new perspective on the factors driving the popularity and spread (or lack of popular engagement with) a given media text and its audience. -

Ten Years Supporting, Delivering & Promoting the Whole Spectrum of Animation

TEN YEARS SUPPORTING, DELIVERING & PROMOTING THE WHOLE SPECTRUM OF ANIMATION Directors Message Wow – we made it to our 10th anniversary!! Who would have thought it? From very humble beginnings – our first festival in 2004 screened at the now-defunct Rupert Street Cinema in Piccadilly – to LIAF 2013, 10 days at 3 different venues. We have survived - sort of. Over 10 years we’ve received more than 12,000 entries, screened more than 2,500 films, and had some of the most talented animators in the world come and hang out with us. And we’ve had a ball on the way. It’s time to blow our own trumpet. As well as being the largest festival of it’s kind in the UK in terms of films and programmes screened, we have a substantial touring component and we run satellite events all year-round. We’ve screened at festivals, cinemas, theatres and colleges all around the world and in the UK and hopefully we have spread the word that animation is a valid artform that is only limited by the animator’s imagination. In short, our maxim is that in animation anything can happen. Long may this be. There are far too may people to thank here (hopefully you know who you are) but the guidance and immense work-rate of my co-Director Malcolm Turner has to be acknowledged. Way back when in our ground zero - actually in the year 1999 - I still vividly recall that very first meeting Malcolm and I had with our then-colleague Susi Allender in the back garden of our Melbourne flat. -

Printable Syllabus Here

ART 4101 MOVING IMAGE ART OSU ART & TECHNOLOGY SPRING 2021 JANUARY 11- APRIL 23 SYLLABUS CLASS SESSIONS Tuesdays & Thursdays 8:10AM - 10:55AM EST Hybrid Delivery Method Located on ~*~The Internet~*~ ++ occasionally Hopkins Hall 156 INSTRUCTOR Dalena Tran [email protected] Oice hours by appointment DESCRIPTION This studio course critically engages with moving images. We will generate, manipulate, and animate digital imagery into durative, artistic projects. To develop a broader context around moving images, we will watch, read, create, critique, and discuss. We will screen time-based works and study a collection of texts in relationship to historical, contemporary, and experimental uses of time-based digital media. The developments in digital imaging, computer simulation, and animation has shied notions of cinema and techniques of film/artmaking into ever-evolving forms. In the beginning of this course, we will create a constellation of short, experimental projects that aim to familiarize our art practices with various media, soware, techniques, contexts, and implications of animated computer imaging. The later duration of this course is aimed at synthesizing the relevant technical and creative concepts learned throughout the course into a self-directed, final project. Final works will be publicly exhibited at the end of the semester. Experimentation with media, non-traditional tools, platforms, and methods are encouraged. LEARNING GOALS Create original art using digital imaging, computer animation, and sequencing tools such as Blender, -

Summer 08 Continuum FINAL.Indd

The For family, friends, and alumni of Cistercian Preparatory School Summer 2008 MMakingaking A T wworkoRrk Geoff Marslett ‘92 Earning a living in with scenes from his upcoming feature, Mars, the arts can test even and the short, Bubblecraft. the most talented The Memorare Society was established for members of our community who wish to include Cistercian in their financial plans through bequests, trusts, wills, or other means. It’s a wonderful way for people to include the school as part of their long-term financial planning. As a member of the Memorare Society, you’ll enable us to continue educating Cistercian students and the Abbey’s young monks for many years. All while ensuring your legacy with Cistercian for generations to come. After all, Memorare means “remember.” To find out if the Memorare Society is right for you and your family, simply contact Jennifer Rotter in the Development Office today. All enquiries are welcome. Call 469-499-5406, or send an email to [email protected]. Required reading for the school year This edition will inspire you to pursue your highest ideals and goals he best preparation for this school year, I think, himself, while contemplating the transition from Tis to read this edition of The Continuum from home and Cistercian to college. front to back. You will fi nd stories to help you set Most importantly, however, this edition of The CISTERCIAN goals for the year and fi nd the motivation to keep Continuum provides many reasons for gratitude. PREPARATORY working toward them. The remodeling of the Upper School is com- SCHOOL Our cover story, “Mak- ing to a completion. -

Cailen Pybus

Pybus 1 Introduction Beyond the entrance, passing under an enormous sculpture of a minotaur’s head, you walk down a long, straight, narrow corridor with walls of indistinguishable height disappearing into blackness. Despite the sense of crampt emptiness the corridor gives you, you are all the while comforted by the presence of dozens of other wonder-struck visitors. Your group distributes among four different floors where they remain for the rest of the excursion. Your group arrives at the first chamber and watches a huge film projected on both the floor and a wall in a way you’ve never seen before. The film finishes and you proceed behind the wall screen and through the narrow maze of the second chamber while formless ‘moving’ sounds and synchronized blinking lights reflect infinitely from mirrors all around you, and you find yourself in contemplation. Finally your group arrives at the third chamber, the last chamber, where you are once again confronted by a strange screen composed of five smaller screens arranged in a cross. You twist and turn your neck to see everything you can on the screens. You’re too close to see everything on the screens in a single gaze. You move and look and absorb every strange emotion unfold on the screen and around you until the film abruptly ends. You leave the pavilion. Emerging from darkness you see an elevated view of the St. Lawrence River and the remaining Expo grounds of Ile-Notre-Dame and Ile-Sainte-Helene in the distance. Such was the experience of the Labyrinth pavilion from the National Film Board of Canada at Expo ’671. -

Ambler Theater

Ambler Theater Previews65A SEPTEMBER - DECEMBER 2008 Keira Knightley and Ralph Fiennes in THE DUCHESS and Ralph FiennesKeira Knightley in INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS A MBLERT HEATER.ORG 215 345 7855 Welcome to the nonprofit Ambler Theater The Ambler Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. ADMISSION Give us your feedback Your film experience is the most important thing to us, so we welcome your feedback. Please let us know what we can do General ............................................................$8.50 better. Call (215) 345-7855, or email us at Members .........................................................$4.50* [email protected] Seniors (62+) Children under 18 and When will films play? Students w/valid I.D. .....................................$6.50 Matinee (before 5:00 pm) ...............................$6.50 Main Attractions Wed Early Matinee (before 2:30 pm) ...............$5.00 Film Booking. Our main films play week-to-week from Friday Affiliated Theaters Members** .........................$5.50 through Thursday. Every Monday we determine what new films will start on Friday, what current films will end on Thursday, **Affiliated Theaters Members and what current films will continue through Friday for another The Ambler Theater, the County Theater, and the Bryn Mawr Film In- week. All films are subject to this week-to-week decision-mak- ing process. We try to play all of our Main Attraction films as stitute have reciprocal admission benefits. Your Ambler membership soon as possible. -

Gsff18 Brochure

CONTENTS TICKETS Introduction 3 £7.00 (£5.00 concessions) Opening Screening: What Makes A Glasgow Short? 3 Concessions apply to children under 16, full-time International Competition 4–5 students, over-60s, Jobseekers Allowance or Income Support recipients and registered disabled people. Please Award Winners 5 produce proof of eligibility when purchasing or collecting Scottish Competition 6 tickets. Some events are individually priced or free of Blueprint: Scottish Independent Shorts 7 charge – see listings for details. GFT CineCard and 15–25 NFTS Scotland presents Eva Riley 7 Card discounts apply. Ten Years of FilmG 7 CERTIFICATION The Forgotten Films of Falconer Houston 7 Films not certified by the BBFC are marked N/C and Calendar 8–9 accompanied by an age recommendation e.g. N/C 15 Kalampag Tracking Agency: 10 + (suitable for ages 15 and older, no-one under 15 will Experimental Films & Videos from the Philippines be admitted). Screenings marked with this icon are Nguyễn Trinh Thi 10 captioned for deaf and hard-of-hearing audiences, with BSL interpreters for Q&As. Death and Killing in Southeast Asia 10 Symposium: Archives, Activism, Aesthetics 10 HOW TO BUY Apichatpong Weerasethakul 11 In Advance Kevin Jerome Everson: now y’all have to look at us 11 From Thursday 1 February tickets can be purchased Babe live + New Scottish Music Videos 12 from glasgowfilm.org/gsff. Tickets can be purchased online until one hour before the screening. Alternatively, Big Fun In The Big Town + Hip Hop Shorts 12 from Thursday 1 February tickets can be purchased + after party with Tomboy from Glasgow Film Theatre box office, in person or by Transit Arts presents Soft Cells 13 telephone (£1.50 booking fee applies to telephone Don Hertzfeldt: World of Tomorrow 1 & 2 13 bookings). -

Sundance Institute Announces Short Film Awards for 2016 Sundance Film Festival

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: January 26, 2016 Elizabeth Latenser 435.658.3456 [email protected] SUNDANCE INSTITUTE ANNOUNCES SHORT FILM AWARDS FOR 2016 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL Thunder Road Wins Grand Jury Prize (LR) Maman(s), Credit: Sundance Film Festival; The Procedure, Credit: Jacob Rosen; Thunder Road, Credit:Jim Cummings. Park City, UT — Sundance Institute announced today the jury prizes in short filmmaking at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival. The Short Film Grand Jury Prize, awarded to one film in the program of 72 short films selected from 8,712 submissions, went to Thunder Road by director and screenwriter Jim Cummings. The awards were presented at a ceremony in Park City, Utah; full video of the ceremony is at youtube.com/sff. The Short Film program is presented by YouTube. This year's Short Film jurors are: star and cocreator of Comedy Central’s Key & Peele, KeeganMichael Key; development executive at Amazon Studios, Gina Kwon; and chief film critic for MTV, Amy Nicholson. Short Film awards winners in previous years include World of Tomorrow by Don Hertzfeldt, SMILF by Frankie Shaw, Of God and Dogs by Abounaddara Collective, Gregory Go Boom by Janicza Bravo, The Whistle by Grzegorz Zariczny, Whiplash by Damien Chazelle, FISHING WITHOUT NETS by Cutter Hodierne, The Tsunami and the Cherry Blossom by Lucy Walker and The Arm by Brie Larson, Sarah Ramos and Jessie Ennis. The short film program at the Festival is the centerpiece of Sundance Institute’s yearround efforts to support short filmmaking, including a series of daylong workshops and a traveling program of short films. -

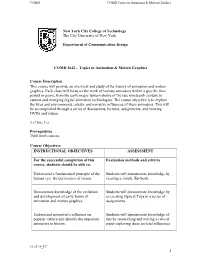

COMD 3642 – Topics in Animation & Motion Graphics

COMD COMD Topics in Animation & Motion Graphics New York City College of Technology The City University of New York Department of Communication Design COMD 3642 – Topics in Animation & Motion Graphics Course Description This course will provide an overview and study of the history of animation and motion graphics. Each class will focus on the work of various animators within a specific time period or genre, from the early magic lantern shows of the late nineteenth century to current and emerging digital animation technologies. The course objective is to explore the lives and environments, artistic and narrative influences of these animators. This will be accomplished through a series of discussions, lectures, assignments, and viewing DVDs and videos. 3 cl hrs, 3 cr Prerequisites 3500 level courses Course Objectives INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES ASSESSMENT For the successful completion of this Evaluation methods and criteria course, students should be able to: Understand a fundamental principle of the Students will demonstrate knowledge by human eye: the persistence of vision. creating a simple flip-book. Demonstrate knowledge of the evolution Students will demonstrate knowledge by and development of early forms of re-creating Optical Toys in a series of animation and motion graphics. assignments. Understand animation's influence on Students will demonstrate knowledge of popular culture and identify the important this by researching and writing a critical animators in history. paper exploring these societal influences. 10.25.14_LC 1 COMD COMD Topics in Animation & Motion Graphics INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES ASSESSMENT Define the major innovations developed by Students will demonstrate knowledge of Disney Studios. these innovations through discussion and research. -

Norfolk Chamber Music Festival Also Has an Generous and Committed Support of This Summer’S Season

Welcome To The Festival Welcome to another concerts that explore different aspects of this theme, I hope that season of “Music you come away intrigued, curious, and excited to learn and hear Among Friends” more. Professor Paul Berry returns to give his popular pre-concert at the Norfolk lectures, where he will add depth and context to the theme Chamber Music of the summer and also to the specific works on each Friday Festival. Norfolk is a evening concert. special place, where the beauty of the This summer we welcome violinist Martin Beaver, pianist Gilbert natural surroundings Kalish, and singer Janna Baty back to Norfolk. You will enjoy combines with the our resident ensemble the Brentano Quartet in the first two sounds of music to weeks of July, while the Miró Quartet returns for the last two create something truly weeks in July. Familiar returning artists include Ani Kavafian, magical. I’m pleased Melissa Reardon, Raman Ramakrishnan, David Shifrin, William that you are here Purvis, Allan Dean, Frank Morelli, and many others. Making to share in this their Norfolk debuts are pianist Wendy Chen and oboist special experience. James Austin Smith. In addition to I and the Faculty, Staff, and Fellows are most grateful to Dean the concerts that Blocker, the Yale School of Music, the Ellen Battell Stoeckel we put on every Trust, the donors, patrons, volunteers, and friends for their summer, the Norfolk Chamber Music Festival also has an generous and committed support of this summer’s season. educational component, in which we train the most promising Without the help of so many dedicated contributors, this festival instrumentalists from around the world in the art of chamber would not be possible. -

FFF 2012 Program.Qxp

Opening Events! • Tuesday, March 6th Wednesday Morning • March 7th 12:00 p.m. Opening Press Conference at the Fargo Theatre 9:00 a.m. Registration / Box Office Opens Best in Show Announcements 10:00 a.m. My Hometown • Animation (7 min) Directed by Jerry Levitan and Terry Tompkins, PRE-PARTY • 5:00 - 7:45 p.m. Toronto, ON, Canada – In 2009, Yoko Ono wrote a 220 Broadway • Downtown Fargo timeless message of home, hope, faith and love. Weaving a storyline that encompasses children and places from all over the world, this animation plays out 8:00 p.m. LIVE! AND IN PERSON – Jay and Silent Bob Get Old My Hometown Yoko’s instructional positivism, using a backdrop of her voice, recorded especially for this film. By way of a New Jersey Quick Stop, Kevin Smith and Jason Mewes 10:10 a.m. Falling • Experimental (7 min) Directed by Karim Azimi, Aradbil, Iran have become bona fide pop culture icons. Their on-screen alter egos Jay and A human being is exiled to roam and endure loneliness. Silent Bob are far more than small-town, small-time pot dealers. Armed with Smith’s trademark 10:20 a.m. Serial Killer • Student Film (3 min) Directed by Adam Jacobs, Brooklyn Park, MN dialogue (peppered with carnal references, cultural observations, and pop-culture diatribes) they Two chaps have an argument about the mysterious man skipping towards them. Falling are pranksters, lovers, action heroes and prophets. 10:25 a.m. Heliotropes • Animation (4 min) Directed by Michael Langan – The parallel goals of man and nature are explored through the most primitive “One speaks.. -

Of SHOWS SHOW ANIMATION

11 ALL NEW ANIMATED INTERNATIONAL SHORTS ACME FILMWORKS PRESENTS the 17TH ANNUAL ANIMATION of Buy DVDs and downloads of films from past SHOW SHOWS Animated Show of Shows www.animationshowofshows.com “ The animated short film is a great art form - always beautiful, innovative, and extremely entertaining. The Animation Show of Shows is the best place to see all the latest and greatest animated short films. You will never be disappointed. ” John Lasseter, Chief Creative Officer Pixar and Walt Disney Animation Studios * Special appearance by Curator, Producer Ron Diamond, check theaters for dates and times. * Hollywood, CA • Arclight Cinemas • Sept 24 - Oct 1 Silver Spring, MD • AFI Silver Theatre • Oct 23 - Oct 29 * Santa Ana, CA • The Frida Cinema • Oct 2 - Oct 8 * Seattle, WA • SIFF Egyptian Theatre • Oct 30 - Nov 5 GLOUSTER, MA, • The Cape Ann Cinema • Oct 2 - Oct 4 Larkspur, CA • The Lark Theater • Oct 30 - Nov 5 ALBANY, NY • Spectrum 8 Theatres • Oct 5 one night only * VANCOUVER, BC • Rio Theatre • Nov 1 one night only * San Francisco, CA • Vogue Theatre • Oct 9 - Oct 15 * PORTLAND, OR • CINEMA 21 Theatre • Nov 13 - Nov 19 * CHICAGO, IL • Gene Siskel Film Center • Oct 16 - Oct 22 * Eugene, OR • Bijou Art Cinemas • Nov 13 - Nov 19 © 2015 The Animation Show of Shows, Inc. PittsburgH, PA • Melwood Screening Room • Oct 16 - Oct 22 Denver, CO • Denver Film Society SIE FilmCenter • Nov 27 - Dec 3 The 17th Annual (2014 - 2015) Animation Show of Shows A whimsical story about living an impractical life based on a childhood promise. While playing on stilts as a child, Percival Pilts declares that he’ll ‘never again let his John Lewis and Janette Goodey’s feet touch the ground!’ Australia 2014 The Story of Percival Pilts Golden Gate Award, San Francisco Intl.