Problem Bodies and Sideshow Space: a Study of the Twentieth Century Sideshow in Blackpool 1930-1940

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Circus Friends Association Collection Finding Aid

Circus Friends Association Collection Finding Aid University of Sheffield - NFCA Contents Poster - 178R472 Business Records - 178H24 412 Maps, Plans and Charts - 178M16 413 Programmes - 178K43 414 Bibliographies and Catalogues - 178J9 564 Proclamations - 178S5 565 Handbills - 178T40 565 Obituaries, Births, Death and Marriage Certificates - 178Q6 585 Newspaper Cuttings and Scrapbooks - 178G21 585 Correspondence - 178F31 602 Photographs and Postcards - 178C108 604 Original Artwork - 178V11 608 Various - 178Z50 622 Monographs, Articles, Manuscripts and Research Material - 178B30633 Films - 178D13 640 Trade and Advertising Material - 178I22 649 Calendars and Almanacs - 178N5 655 1 Poster - 178R47 178R47.1 poster 30 November 1867 Birmingham, Saturday November 30th 1867, Monday 2 December and during the week Cattle and Dog Shows, Miss Adah Isaacs Menken, Paris & Back for £5, Mazeppa’s, equestrian act, Programme of Scenery and incidents, Sarah’s Young Man, Black type on off white background, Printed at the Theatre Royal Printing Office, Birmingham, 253mm x 753mm Circus Friends Association Collection 178R47.2 poster 1838 Madame Albertazzi, Mdlle. H. Elsler, Mr. Ducrow, Double stud of horses, Mr. Van Amburgh, animal trainer Grieve’s New Scenery, Charlemagne or the Fete of the Forest, Black type on off white backgound, W. Wright Printer, Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, 205mm x 335mm Circus Friends Association Collection 178R47.3 poster 19 October 1885 Berlin, Eln Mexikanermanöver, Mr. Charles Ducos, Horaz und Merkur, Mr. A. Wells, equestrian act, C. Godiewsky, clown, Borax, Mlle. Aguimoff, Das 3 fache Reck, gymnastics, Mlle. Anna Ducos, Damen-Jokey-Rennen, Kohinor, Mme. Bradbury, Adgar, 2 Black type on off white background with decorative border, Druck von H. G. -

Xochitl Sosa- Circus Performer 2126 Emerson St Berkeley, CA 94705 Phone: (510)219-5157 E-Mail: [email protected]

Xochitl Sosa- Circus Performer 2126 Emerson st Berkeley, CA 94705 Phone: (510)219-5157 www.xochitlsosa.com E-mail: [email protected] Skills Dance Trapeze – Static Trapeze - Silks – Rope/Corde Lisse – Duo Trapeze – Straps – Acrobatics – Lyra/Cerceaux – Partner acrobatics – Stilting – Modern Dance Height: 5’5” Weight: 127 lbs Hair Color: Brown Experience Acrobatic Conundrum: Dance Trapeze, Duo Trapeze, Rope, partner acrobatics, acting (USA tour) 2016 Rolling in the Hay Cabaret: Dance trapeze (San Francisco, CA) 2015 Circovencion Mexicana: Performer on Dance Trapeze & Workshop instructor (Oaxtepec,Morelos MX) 2015 Yerba Buena Night: Performer on Dance Trapeze & Rope (San Francisco, CA) 2014-2015 Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Festival: Performer on Silks (San Francisco, CA) 2015 Topsy Turvy Queer arts Festival: Performer on Dance Trapeze (San Francisco, CA) 2015 Aerial Acrobatics Festival: Performer on Dance Trapeze (Denver,CO) 2014 Aerial Horizon: Performer on Dance Trapeze (San Antonio, TX) 2014 Crash Alchemy/ AgentRed: Dancer, Lyra, Trapeze, Partner Acrobatics, Contortion (USA) 2010-2015 Sky Candy Productions: Trapeze, Duo trapeze, Dancer, partner acrobatics, instructor (Austin,TX) 2010-2015 NASCAR’s Wild Asphalt Circus – Hellzapoppin Sideshow: Static Trapeze, Silks (Dallas,TX) 2013 Formula One Inaugeration: OMEGA events: Duo Trapeze, Static Trapeze (Austin,TX) 2012 Education Leslie Tipton: Contortion San Francisco, CA 2015 Chloe Farah: Duo Trapeze, Dance Trapeze, Rope Montreal, Canada 2015 Itzel Virguenza: Duo Trapeze, Dance Trapeze Montreal, Canada 2015 Victor Fomine: Straps Montreal, Canada 2015 Serchmaa Byamba: Contortion San Francisco, CA 2014-2015 Rachel Walker: Dance Trapeze Montreal , Canada 2013 NECCA Protrack Program Brattleboro, Vermont 2012-2013 (coaches: Aimee Hancock, Elsie & Serenity Smith, Bill Forchion, Sellam Ouahabi) NECCA Bootcamp Brattleboro, Vermont 2011 Sky Candy Austin Austin, TX 2010- 2014 Camp Winnarainbow (coahing under: Carrie Heller) Laytonville, CA summers 2000- 2009 2 . -

Sound Recording in the British Folk Revival: Ideology, Discourse and Practice, 1950–1975

Sound recording in the British folk revival: ideology, discourse and practice, 1950–1975 Matthew Ord Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD International Centre for Music Studies Newcastle University March 2017 Abstract Although recent work in record production studies has advanced scholarly understandings of the contribution of sound recording to musical and social meaning, folk revival scholarship in Britain has yet to benefit from these insights. The revival’s recording practice took in a range of approaches and contexts including radio documentary, commercial studio productions and amateur field recordings. This thesis considers how these practices were mediated by revivalist beliefs and values, how recording was represented in revivalist discourse, and how its semiotic resources were incorporated into multimodal discourses about music, technology and traditional culture. Chapters 1 and 2 consider the role of recording in revivalist constructions of traditional culture and working class communities, contrasting the documentary realism of Topic’s single-mic field recordings with the consciously avant-garde style of the BBC’s Radio Ballads. The remaining three chapters explore how the sound of recorded folk was shaped by a mutually constitutive dialogue with popular music, with recordings constructing traditional performance as an authentic social practice in opposition to an Americanised studio sound equated with commercial/technological mediation. As the discourse of progressive rock elevated recording to an art practice associated with the global counterculture, however, opportunities arose for the incorporation of rock studio techniques in the interpretation of traditional song in the hybrid genre of folk-rock. Changes in studio practice and technical experiments with the semiotics of recorded sound experiments form the subject of the final two chapters. -

CY 2001 Compared to CY 2000

Source: 2001 ACAIS Summary of Enplanement Activity CY 2001 Compared to CY 2000 Svc Hub CY 2001 CY 2000 % Locid Airport Name City ST RO Lvl Type Enplanement Enplanement Change ATL The William B Hartsfield Atlanta International Atlanta GA SO P L 37,181,068 39,277,901 -5.34% ORD Chicago O'Hare International Chicago IL GL P L 31,529,561 33,845,895 -6.84% LAX Los Angeles International Los Angeles CA WP P L 29,365,436 32,167,896 -8.71% DFW Dallas/Fort Worth International Fort Worth TX SW P L 25,610,562 28,274,512 -9.42% PHX Phoenix Sky Harbor International Phoenix AZ WP P L 17,478,622 18,094,251 -3.40% DEN Denver International Denver CO NM P L 17,178,872 18,382,940 -6.55% LAS Mc Carran International Las Vegas NV WP P L 16,633,435 17,425,214 -4.54% SFO San Francisco International San Francisco CA WP P L 16,475,611 19,556,795 -15.76% IAH George Bush Intercontinental Houston TX SW P L 16,173,551 16,358,035 -1.13% Minneapolis-St Paul International/Wold- MSP Chamberlain/ Minneapolis MN GL P L 15,852,433 16,959,014 -6.53% DTW Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Detroit MI GL P L 15,819,584 17,326,775 -8.70% EWR Newark International Newark NJ EA P L 15,497,560 17,212,226 -9.96% MIA Miami International Miami FL SO P L 14,941,663 16,489,341 -9.39% JFK John F Kennedy International New York NY EA P L 14,553,815 16,155,437 -9.91% MCO Orlando International Orlando FL SO P L 13,622,397 14,831,648 -8.15% STL Lambert-St Louis International St. -

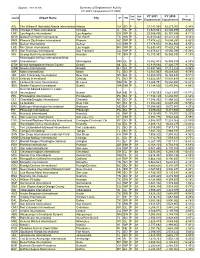

Airport Enplanement Activity for CY 2001 Listed by State and Rank

Source: 2001 ACAIS Airport Enplanement Activity For CY 2001 12/11/2002 Listed by State and Rank Order within the State Service Hub 2001 ST Region City Locid Airport Name Rank Level Type Boardings AK AL Anchorage ANC Ted Stevens Anchorage International P M 60 2,419,261 AK AL Juneau JNU Juneau International P S 122 402,117 AK AL Fairbanks FAI Fairbanks International P S 124 384,828 AK AL Bethel BET Bethel P N 191 132,665 AK AL Kenai ENA Kenai Municipal P N 206 106,673 AK AL Ketchikan KTN Ketchikan International P N 208 102,634 AK AL Sitka SIT Sitka Rocky Gutierrez P N 234 72,912 AK AL Kodiak ADQ Kodiak P N 246 62,768 AK AL Kotzebue OTZ Ralph Wien Memorial P N 254 57,841 AK AL Nome OME Nome P N 257 55,922 AK AL King Salmon AKN King Salmon P N 274 44,335 AK AL Ketchikan 5KE Ketchikan Harbor GA - 281 38,077 AK AL Barrow BRW Wiley Post-Will Rogers Mem P N 282 38,068 AK AL Dillingham DLG Dillingham P N 284 37,545 AK AL Homer HOM Homer P N 294 32,936 AK AL Unalaska DUT Unalaska P N 297 31,409 AK AL Deadhorse SCC Deadhorse P N 330 22,817 AK AL Valdez VDZ Valdez Pioneer Field P N 337 20,384 AK AL Anchorage LHD Lake Hood P N 338 20,363 AK AL Cordova CDV Merle K (Mudhole) Smith P N 341 19,261 AK AL Petersburg PSG Petersburg James A Johnson P N 348 18,292 AK AL Kodiak KDK Kodiak Municipal P N 349 18,285 AK AL Aniak ANI Aniak P N 354 16,963 AK AL Yakutat YAK Yakutat P N 363 14,765 AK AL Gustavus GST Gustavus P N 364 14,652 AK AL Taku Harbor A43 Taku Harbor GA - 365 14,354 AK AL Manokotak 17Z Manokotak P N 381 12,588 AK AL Red Dog AED Red Dog GA - 382 12,472 AK AL Iliamna ILI Iliamna P N 389 12,023 AK AL Anchorage MRI Merrill Field P N 407 10,572 AK AL Wrangell WRG Wrangell P N 411 10,231 AK AL Skagway SGY Skagway P N 416 10,168 AK AL Metlakatla MTM Metlakatla P N 418 10,026 AK AL Haines HNS Haines CS - 424 9,652 AK AL Hoonah HNH Hoonah CS - 427 9,510 AK AL Galena GAL Edward G. -

Keith Resume

347-404-0422 Height: 5’ 11’’ [email protected] Weight: 185 lbs. bindlestiff.org Hair: Dk Brown, Long Keith Nelson Eyes: Brown VARIETY ENTERTAINER * J UGGLER * S IDESHOW MARVEL * C LOWN * M ASTER OF CEREMONIES PERFORMING PROFESSIONALLY SINCE 1994 Performance Skills Sideshow Feats: Circus Skills: Diabolo Bullwhip Sword Swallowing Clowning Balloon Sculpture Archery Fire-eating Stilt Walking Balancing Gun Spinning Bed of Nails Unicycling Mouth sticks Human Blockhead Basic Tumbling/Acrobatics Bottle and glass tricks Additional Skills Mental Floss Tuba Straight Jacket Escape Prop Manipulation: Western Skills: Concertina Juggling Trick Rope Spinning Magic Plate Spinning Knife Throwing Basic Tap Dancing Work Experience - Venues & Festivals Avery Fischer Hall (w/ Ornette Coleman), NYC King Opera House, Van Buren, AK Hall & Christ’s World of Wonders, NJ San Diego Street Scene, CA Yale Cabaret, Yale University, CT Blue Angel Cabaret, NY Toyota Comedy Festival, NY Knitting Factory, NY Burning Man Festival, NV Bonnaroo, TN Glastonbury Festival, UK All Good Festival, WV Coney Island Sideshow by the Seashore, NY MGM Grand Theater, Washington, DC Wild Style Tattoo Convention, Austria Borgata Hotel and Casino, Atlatnic City Television/Film/Video Late Late Show with James Corden “The Today Show,” NBC “On the Inside,” BBC Late Night w/ David Letterman,” CBS “Twisted Lives of Contortionist,” “Tudo de Bom,” MTV Brazil “Carson Daly Show,” NBC Discovery “Tonigh Show wih Jay Leno” “Oddville,” MTV “Rock of Ages,” VH-1 “OZ.” HBO “212,” FOX Clients Bendel’s -

The University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire “Flirting and Boisterous Conduct Prohibited”: Women's Work in Wisconsin Circuse

THE UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN – EAU CLAIRE “FLIRTING AND BOISTEROUS CONDUCT PROHIBITED”: WOMEN’S WORK IN WISCONSIN CIRCUSES: 1890-1930 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY REBECCA N. REID EAU CLAIRE, WISCONSIN MAY 2010 Copyright © 2010 by Rebecca N. Reid All rights reserved Because I was born a member of the so-called weaker sex and had to work out some kind of career for myself… -Mabel Stark, tiger trainer CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . vi GLOSSARY . .vii ABSTRACT . .ix Step Right Up! . 2 Wisconsin: Center of the Circus World. .7 How Many Women?. 8 Circus Women in Popular Media . 11 Circus Propaganda?. .12 “The Circus Girl is Industrious”. .14 Notable Circus Woman: Mayme Ward . 15 Sunday School Show . 16 Family Connections . 18 Notable Circus Women: The Rooneys . .19 Bare Legs and Bloomers . 20 Vaudeville and Burlesque. .21 Hoochie Coochie Girls and Grifters . .23 Freaks . .24 City on a Train . 26 The Dining Tent . 28 Queen’s Row . 29 Salaries and Wages . .32 iv The Tent, Folded . .36 APPENDIX . 38 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 43 v ILLUSTRATIONS Figures 1. Mayme Ward, catcher . .15 2. Lizzie Rooney, 1898 . .19 vi GLOSSARY ballyhoo. A sideshow performer that came out of the sideshow tent to entice marks; often a scantily clad woman, either a snake charmer or tattooed lady. ballet girl. A young woman who appeared in the opening spectacle or parade. Little dancing skill was required of ballet girls, as their primary job was to look pretty and entice customers to buy a ticket to the circus. -

FY 2015 AIP Grants Awarded in FY 2015 by State

FAA Airports AIP Grants Awarded by State: FY 2015 AIP Grants Awarded in FY 2015 by State Service Grant Federal City Airport/Project Location Description of Project Level No. Funds Alabama General Alabaster Shelby County 18 261,448 Construct Building Aviation Albertville Regional-Thomas General Albertville 25 142,211 Rehabilitate Apron J Brumlik Field Aviation Alexander General Thomas C Russell Field 16 1,009,662 Extend Taxiway City Aviation General Aliceville George Downer 13 349,205 Construct Fuel Farm, Rehabilitate Runway Aviation South Alabama Regional at General Andalusia 20 106,598 Install Perimeter Fencing Bill Benton Field Aviation General Anniston Anniston Regional 31 150,000 Rehabilitate Apron, Rehabilitate Runway Aviation General Atmore Atmore Municipal 12 1,841,856 Improve Runway Safety Area, Rehabilitate Runway Aviation General Bay Minette Bay Minette Municipal 11 51,837 Conduct Environmental Study Aviation Bessemer Bessemer Reliever 14 682,500 Rehabilitate Apron, Rehabilitate Taxiway Birmingham-Shuttlesworth Birmingham Primary 96 3,715,596 Expand Terminal Building International Total AIP Grant Funds Awarded 11/13/2017 Page 1 of 131 FY 2015 APP-500 Service Grant Federal City Airport/Project Location Description of Project Level No. Funds Birmingham-Shuttlesworth Birmingham Primary 97 482,820 Acquire Snow Removal Equipment International Birmingham-Shuttlesworth Birmingham Primary 98 2,590,500 VALE Infrastructure International General Brewton Brewton Municipal 13 271,990 Construct Taxiway, Improve Airport Drainage Aviation General -

Representations of Intersex People in Circus and Sideshow Novels

Networking Knowledge 10(3)Sex and Sexualities in Popular Culture (Oct. 2017) The Hidden Sex: Representations of Intersex People in Circus and Sideshow Novels NAOMI FRISBY, Sheffield Hallam University ABSTRACT Despite being the hidden sex in society, intersex people with ambiguous genitalia are visible in a number of circus and sideshow novels. These characters are often used as plot devices, performing a stable gender identity whilst concealing their intersex status for the sake of the plot. They are portrayed as deceptive and licentious, their identities placing them outside of the sex and gender binaries and leaving them dehumanised. It is only in Pantomime by Laura Lam that the possibility of an alternative portrayal is glimpsed, although questions regarding the sex and gender binaries and non-normative sexuality remain. KEYWORDS Intersex, Gender, Performativity, Sexuality, Literature Introduction The US publishing industry came under scrutiny in 2015 due its failure to offer a true reflection of the society in which we live. A ‘Diversity Baseline Survey’ (2015) conducted by the publisher Lee & Low Books sought to explain why, in the past twenty years, the number of diverse books published in the USA never exceeded an average of 10%. The authors of the survey drew a correlation between the high percentage of white (80), cis (98.7), heterosexual (88.2), non-disabled (92.8) people working in the publishing industry and the lack of broad representation in published books. One genre in which we might expect to find a diverse range of characters is circus and sideshow literature. The circus has been seen as a safe space for those who fall outside of mainstream society, particularly those with non-normative bodies1. -

America's News English Big Top Chicago Sun-Times - Friday, April 6, 2001 Author: Delia O'hara

America's News English big top Chicago Sun-Times - Friday, April 6, 2001 Author: Delia O'Hara `Under the Big Top' Through Sept. 9 Museum of Science and Industry, 57th Street and South Lake Shore Free with museum admission (773) 684-1414 A circus must appeal to people at a very basic level. At a time when other traditional entertainments are withering, the circus is evolving, gaining strength, astonishing new generations of children with its distinctive panoply of sights, sounds, smells and emotions. Now the Museum of Science and Industry will take us "Under the Big Top" to look at the mystique of the circus. Beginning today, the Hyde Park museum will present a 15,000-square-foot exhibit based on the traveling "Circus Magicus," more than 200 artifacts, photographs and videos of circus history developed by the Musee de La Civilisation in Quebec. The exhibit was co- produced by Cirque du Soleil, one of the performance groups that is re-creating the concept of the circus in our time. Some of the artifacts are remarkable, including a cast of a bronze statuette of an acrobat from ancient Rome, the makeup of famous American clowns, photographs such as one of the bearded woman Annie Jones, and a reproduction of a show costume worn by the great acrobat Karl Wallenda, who died performing his act in the 1960s. In addition, the museum staff has developed some lively components of their own to complement Circus Magicus. "Giant Science Circus" highlights the science behind the magic. How can tightrope walkers stay on a cable five-eighths of an inch thick? Why is the diameter of a circus ring always 42 feet? The answers to these questions are based in physics. -

Towards a Genealogy of Circus Cinema by Brian Mcilroy

The Big Top on Screen: Towards a Genealogy of Circus Cinema By Brian McIlroy [delivered as a conference paper at the Film Studies Association of Canada annual conference at UBC on June 5th, 2019] Ever since the contemporary circus arose to significant public attention in the 1970s and 1980s, a form which cast away the use of animals in favour of the supremacy of the human body, general themes, theatricality, basic narrative, and modest character development, circus both recreational and professional has exploded in popularity. Circus themed films have waxed and waned in popularity over the history of cinema, but yet have been omnipresent. For example, the recent musical circus film The Greatest Showman (2017) was made on a budget of $84 million and scored $435 million at the box-office. In a strange way, study of the circus and its representations on screen tells us just as much about conformism as it does about iconoclasm. The freedom of the circus so engrained in the often-used phrase “ran away to the circus” proves to be more often than not a reckoning rather than an escape. And it is undeniable that the circus relies on an economy of exchange that fits within the capitalist system, even if living conditions as itinerant travelers give the illusion of freedom. Theorists such as Paul Bouissac have extolled the characteristics of circus performance as amenable to cybernetic and semiotic approaches in order to understand its cultural meaning, although circus within cinema I argue here goes beyond these formal theoretical structures to suggest that it is a reinsertion of spectacle and disruption within the contemporary cinematic universe, one that cannot be easily controlled. -

That's All Folks! Teacher Resource Pack Primary

That’s All Folks! Teacher Resource Pack Primary INTRODUCTION Audiences have been delighted and entertained by circus and vaudeville acts for generations. The combination of short performances, showcasing music, dance, comedy and magic, was hugely successful among the working classes during the 19th century, alongside burlesque and minstrel shows, up until the 1930s. That’s’ All Folks blends the ideas from vaudeville, or short and entertaining acts, with the skills of modern circus and slapstick clowning to create an energetic show featuring separate yet interlinked routines that explore different characters and situations throughout the history of the theatre. The actors use a range of circus and clowning skills including juggling, acrobalance, bell routines, slapstick, comical routines, musical chairs, improvisation and audience participation to create an entertaining performance reminiscent of the variety shows of yesteryear. These notes are designed to give you a concise resource to use with your class and to support their experience of seeing That’s All Folks! CLASSROOM CONTENT AND CURRICULUM LINKS Essential Learnings: The Arts (Drama), SOSE (History, Culture), English Style/Form: Vaudeville, Commedia dell’Arte, Mask, Traditional and Contemporary Clowning, Melodrama, Visual Theatre, Physical Theatre, Physical Comedy, Circus, non-verbal communication and Mime, Improvisation and Slapstick. Themes and Contexts: Creativity and imagination, awareness, relationships. © 2016 Deirdre Marshall for Homunculus Theatre Co. 1 HISTORICAL CONTEXT Vaudeville Vaudeville was a uniquely American phenomenon and was the most popular form of American entertainment for around fifty years, from its rise in the 1880s, until the 1930s. It played much the same a role in people's lives that radio and later television would for later generations.