1. Bombay-Mumbai and the Dabbawalas: Origin and Development of a Parallel Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

IDL-56493.Pdf

Changes, Continuities, Contestations:Tracing the contours of the Kamathipura's precarious durability through livelihood practices and redevelopment efforts People, Places and Infrastructure: Countering urban violence and promoting justice in Mumbai, Rio, and Durban Ratoola Kundu Shivani Satija Maps: Nisha Kundar March 25, 2016 Centre for Urban Policy and Governance School of Habitat Studies Tata Institute of Social Sciences This work was carried out with financial support from the UK Government's Department for International Development and the International Development Research Centre, Canada. The opinions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect those of DFID or IDRC. iv Acknowledgments We are grateful for the support and guidance of many people and the resources of different institutions, and in particular our respondents from the field, whose patience, encouragement and valuable insights were critical to our case study, both at the level of the research as well as analysis. Ms. Preeti Patkar and Mr. Prakash Reddy offered important information on the local and political history of Kamathipura that was critical in understanding the context of our site. Their deep knowledge of the neighbourhood and the rest of the city helped locate Kamathipura. We appreciate their insights of Mr. Sanjay Kadam, a long term resident of Siddharth Nagar, who provided rich history of the livelihoods and use of space, as well as the local political history of the neighbourhood. Ms. Nirmala Thakur, who has been working on building awareness among sex workers around sexual health and empowerment for over 15 years played a pivotal role in the research by facilitating entry inside brothels and arranging meetings with sex workers, managers and madams. -

Spatial Utopia and Contested Realities

SPATIAL UTOPIA AND CONTESTED REALITIES Anita Patil - Deshmukh Photo Credit : Author 09 / 183 Dattaram Lad Marg, Chinchpokli, Girangaon: Mill workers demonstrating for their right to work and justice. A public space as a platform for showcasing resistance, and gathering support ! Photo Credit : Author Meghwadi in Mumbai right behind Finlay mill is one of the last spots in the island city where farm lands are seen. The constant vigilance and ongoing stuggles of the residents of Meghwadi has kept this piece of land out of the clutches of builders and still functional as a farm. The MCGM has been supportive, helping to safeguard it by building a wall around and restricting access. Photo Credit : Author 184 / 09 SPATIAL UTOPIA AND CONTESTED REALITIES Lalbaug residents are used to walking around the drying chillies on the side walks during summer months. No shenanigan is ever created by anyone about that occupied space! Greed for good taste creates tolerance within the pedestrian or others! Photo Credit : Author 09 / 185 This Rani Baug playground surrounded by greenery is a choice spot for the local youngersters to hone their skills of cricket. Perhaps some day a future master blaster would emerge from this spot! Compared to the open spaces in the suburbs, the island city still has the luxury of many open grounds, parks and gardens. Photo Credit : Author This courtyard of the Kaamgar Sadan Chawl in Curry road, serves as a common space to conduct daily chores of life as well as family celebrations and religious festivals. Reuse, recycle…. Since the homes in chawls are 100-150 sq feet, this community space gathers a special significance in the lives of the residents. -

Mumbai District

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Mumbai District MSME – Development Institute Ministry of MSME, Government of India, Kurla-Andheri Road, Saki Naka, MUMBAI – 400 072. Tel.: 022 – 28576090 / 3091/4305 Fax: 022 – 28578092 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.msmedimumbai.gov.in 1 Content Sl. Topic Page No. No. 1 General Characteristics of the District 3 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 3 1.2 Topography 4 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 5 1.4 Forest 5 1.5 Administrative set up 5 – 6 2 District at a glance: 6 – 7 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Areas in the District Mumbai 8 3 Industrial scenario of Mumbai 9 3.1 Industry at a Glance 9 3.2 Year wise trend of units registered 9 3.3 Details of existing Micro & Small Enterprises and artisan 10 units in the district. 3.4 Large Scale Industries/Public Sector undertaking. 10 3.5 Major Exportable item 10 3.6 Growth trend 10 3.7 Vendorisation /Ancillarisation of the Industry 11 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 11 3.8.1 List of the units in Mumbai district 11 3.9 Service Enterprises 11 3.9.2 Potentials areas for service industry 11 3.10 Potential for new MSME 12 – 13 4 Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprises 13 4.1 Details of Major Clusters 13 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 13 4.2 Details for Identified cluster 14 4.2.1 Name of the cluster : Leather Goods Cluster 14 5 General issues raised by industry association during the 14 course of meeting 6 Steps to set up MSMEs 15 Annexure - I 16 – 45 Annexure - II 45 - 48 2 Brief Industrial Profile of Mumbai District 1. -

612, Raheja Chambers, Nariman Point, Mumbai-400 021

Ref.No. SH/13/2021 9th April, 2021 BSE Limited. National Stock Exchange of India Ltd., Market-Operation Dept., Exchange Plaza, 5th floor, 1st Floor, New Trading Ring, Plot No. C/1, G. Block, Rotunda Bldg., P.J. Towers, Bandra-Kurla Complex, Dalal Street, Bandra (East), Fort, MUMBAI 400023 MUMBAI – 400051 Sub: Confirmation under SEBI circular SEBI/HO/DDHS/CIR/P/2018/144 dated November 26, 2018. With reference to captioned subject, we hereby confirm that The Supreme Industries Limited does not fall under criteria of Large corporate given under the SEBI circular SEBI/HO/DDHS/CIR/P/2018/144 dated November 26, 2018. Disclosure as required under the aforesaid circular is enclosed for your records. Thanking you, Your faithfully, For The Supreme Industries Ltd. (R. J. Saboo) Vice President (Corporate Affairs) & Company Secretary The Supreme Industries Limited +91(022)22820072,22851656 Regd. Ofi. : 612, Raheja Chambers, Nariman Point, Mumbai-400 021. INDIA +91 (022) 22851657, 30925825 CIN : L35920MH1942PLC0035S4 PAN : AAACT 1344F sil [email protected] Corp. OP. : T T61 & 1162, Solitaire Corporate Park, 167, Guru Hargovindji Marg, Andheri- Ghatkopar Link Road, Chakala, Andheri (East), Mumbai- 400093. INDIA *91 (022) 67710000, 40430000 +91 (022) 67710099, 40430099 sil [email protected] www.supreme.co.in Annexure A Format of the initial Disclosure to be made by an entity identified as a Large corporate Sr. No. Particulars Details 1 Name of the company The Supreme Industries Limited 2 CIN L35920MH1942PLC003554 3 Outstanding borrowing of company as on Nil 31st March, 2021 (in Rs Cr.) 4 Highest Credit Rating During the previous Credit Rating : AA/Stable FY along with name of the Credit Rating Rating Agency: CRISIL Agency 5 Name of Stock Exchanges# in which the fine BSE Limited shall be paid, in case of shortfall in the required borrowing under the framework We confirm that we are not a Large Corporate as per the applicability criteria given under the SEBI circular SEBI/HO/DDHS/CIR/P/2018/144 dated November 26, 2018. -

History of Modern Maharashtra (1818-1920)

1 1 MAHARASHTRA ON – THE EVE OF BRITISH CONQUEST UNIT STRUCTURE 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Political conditions before the British conquest 1.3 Economic Conditions in Maharashtra before the British Conquest. 1.4 Social Conditions before the British Conquest. 1.5 Summary 1.6 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES : 1 To understand Political conditions before the British Conquest. 2 To know armed resistance to the British occupation. 3 To evaluate Economic conditions before British Conquest. 4 To analyse Social conditions before the British Conquest. 5 To examine Cultural conditions before the British Conquest. 1.1 INTRODUCTION : With the discovery of the Sea-routes in the 15th Century the Europeans discovered Sea route to reach the east. The Portuguese, Dutch, French and the English came to India to promote trade and commerce. The English who established the East-India Co. in 1600, gradually consolidated their hold in different parts of India. They had very capable men like Sir. Thomas Roe, Colonel Close, General Smith, Elphinstone, Grant Duff etc . The English shrewdly exploited the disunity among the Indian rulers. They were very diplomatic in their approach. Due to their far sighted policies, the English were able to expand and consolidate their rule in Maharashtra. 2 The Company’s government had trapped most of the Maratha rulers in Subsidiary Alliances and fought three important wars with Marathas over a period of 43 years (1775 -1818). 1.2 POLITICAL CONDITIONS BEFORE THE BRITISH CONQUEST : The Company’s Directors sent Lord Wellesley as the Governor- General of the Company’s territories in India, in 1798. -

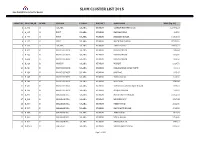

List of Slum Cluster 2015

SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. M.) 1 A_001 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GANESH MURTHI NAGAR 120771.23 2 A_005 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI BANGALIPURA 318.50 3 A_006 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI NARIMAN NAGAR 14315.98 4 A_007 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI MACHIMAR NAGAR 37181.09 5 A_009 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GEETA NAGAR 26501.21 6 B_021 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 939.53 7 B_022 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 1292.90 8 B_023 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 318.67 9 B_029 B MANDVI COLABA MUMBAI MANDVI 1324.71 10 B_034 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI NALABANDAR JOPAD PATTI 600.14 11 B_039 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI JHOPDAS 908.47 12 B_045 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI INDRA NAGAR 1026.09 13 B_046 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MAZGAON 1541.46 14 B_047 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI SUBHASHCHANDRA BOSE NAGAR 848.16 15 B_049 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MASJID BANDAR 277.27 16 D_001 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI MATA PARVATI NAGAR 21352.02 17 D_003 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI BRANHDHARY 1597.88 18 D_006 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI PREM NAGAR 3211.09 19 D_007 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI NAVSHANTI NAGAR 4013.82 20 D_008 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI ASHA NAGAR 1899.04 21 D_009 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SIMLA NAGAR 9706.69 22 D_010 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SHIVAJI NAGAR 1841.12 23 D_015A D GIRGAUM COLABA MUMBAI SIDHDHARTH NAGAR 2189.50 Page 1 of 101 SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. -

Total List of MCGM and Private Facilities.Xlsx

MUNICIPAL CORPORATION OF GREATER MUMBAI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARIES SR SR WARD NAME OF THE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY ADDRESS NO NO 1 1 COLABA MUNICIPALMUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 1ST FLOOR, COLOBA MARKET, LALA NIGAM ROAD, COLABA MUMBAI 400 005 SABOO SIDIQUE RD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY ( 2 2 SABU SIDDIQ ROAD, MUMBAI (UPGRADED) PALTAN RD.) 3 3 MARUTI LANE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY MARUTI LANE,MUMBAI A 4 4 S B S ROAD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 308, SHAHID BHAGATSINGH MARG, FORT, MUMBAI - 1. 5 5 HEAD OFFICE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY HEAD OFFICE BUILDING, 2ND FLOOR, ANNEX BUILDING, MUMBAI - 1, 6 6 HEAD OFFICE AYURVEDIC MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY HEAD OFFICE BUILDING, 2ND FLOOR, ANNEX BUILDING, MUMBAI - 1, 7 1 SVP RD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 259, SARDAR VALLABBHAI PATEL MARG, QUARTERS, A BLOCK, MAUJI RATHOD RD, NOOR BAUG, DONGRI, MUMBAI 400 8 2 WALPAKHADI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 009 9B 3 JAIL RD. UNANI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 259, SARDAR VALLABBHAI PATEL MARG, 10 4 KOLSA MOHALLA MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 20, KOLSA STREET, KOLSA MOHALLA UNANI , PAYDHUNI 11 5 JAIL RD MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 20, KOLSA STREET, KOLSA MOHALLA UNANI , PAYDHUNI CHANDANWADI SCHOOL, GR.FLOOR,CHANDANWADI,76-SHRIKANT PALEKAR 12 1 CHANDAN WADI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY MARG,MARINELINES,MUM-002 13 2 THAKURDWAR MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY THAKURDWAR NAKA,MARINELINES,MUM-002 C PANJRAPOLE HEALTH POST, RAMA GALLI,2ND CROSS LANE,DUNCAN ROAD 14 3 PANJRAPOLE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY MUMBAI - 400004 15 4 DUNCAN RD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY DUNCAN ROAD, 2ND CROSS GULLY 16 5 GHOGARI MOHALLA MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY HAJI HASAN AHMED BAZAR MARG, GOGRI MOHOLLA 17 1 NANA CHOWK MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY NANA CHOWK, FIRE BRIGADE COMPOUND, BYCULLA 18 2 R. S. NIMKAR MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY R.S NIMKAR MARG, FORAS ROAD, 19 3 R. -

Working Papers

Working Papers www.mmg.mpg.de/workingpapers MMG Working Paper 13-04 ● ISSN 2192-2357 SUMEET MHASKAR Indian Muslims in a Global City: Socio-Political Effects on Economic Preferences in Contemporary Mumbai Religious and Ethnic Diversity und multiethnischer Gesellschaften Max Planck Institute for the Study of Max Planck Institute for the Study of Max-Planck-Institut zur Erforschung multireligiöser Sumeet Mhaskar Indian Muslims in a Global City: Socio-Political Effects on Economic Preferences in Contemporary Mumbai MMG Working Paper 13-04 Max-Planck-Institut zur Erforschung multireligiöser und multiethnischer Gesellschaften, Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity Göttingen © 2013 by the author ISSN 2192-2357 (MMG Working Papers Print) Working Papers are the work of staff members as well as visitors to the Institute’s events. The analyses and opinions presented in the papers do not reflect those of the Institute but are those of the author alone. Download: www.mmg.mpg.de/workingpapers MPI zur Erforschung multireligiöser und multiethnischer Gesellschaften MPI for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity, Göttingen Hermann-Föge-Weg 11, 37073 Göttingen, Germany Tel.: +49 (551) 4956 - 0 Fax: +49 (551) 4956 - 170 www.mmg.mpg.de [email protected] Abstract This paper examines the effects of socio-political processes on economic preferences in Mumbai by focussing on the case of Muslim ex-millworkers. The argument of this paper is that the feeling of karahiyat [Urdu: nausea, disgust, hate, etc.] com- bined with suspicion, in terms of terrorism and mafia, creates barriers for Muslims’ employment and self-employment opportunities. The argument is substantiated by using the survey data of 924 ex-millworkers and in-depth interviews with 80 ex-mill- workers collected during 2008-09 and 2010-11. -

VISIONS CATALOGO URBAN VISIONS.Indd

C I T I ES **** E FUTUR he R T O AS F E S MICHELED BONINO I ie T 10 ci F O urban visions ichele Bonino is assistant professor in esigners have always cultivated the risk of authoritarianism and the loss of MArchitectural and Urban Design at the Ddream of long lasting projects. The dialogue. Politecnico di Torino. He holds a PhD in History history of architecture and urban planning of Architecture and Urbanism. He has taught is dotted by this kind of far future visions. evertheless today we are stunned by at Konkuk University in Seoul, at Tsinghua This system has often found partners and Nsome cities which still invest in long- University in Beijing and at Sint Lucas School of sponsors along centuries, until it clogged term scenarios. This fact seems in apparent Architecture at Bruxelles. He is responsible for with the rules of contemporary democratic contradiction with the present moment of the “projects” section in the Italian architecture city: long-term visions often involve the crisis and prudence, when short-term emer- paper “Il Giornale dell’Architettura”. He is the authors of 3 monographs and is curator and 01 translator, with Daniele Vitale, of the writings by Ignasi de Solà-Morales. His writings have been published on “Cahiers de la recherche architec- turale et urbaine”, “Abitare”, “de Architect”, “Controspazio”, “Parametro”, “Ilsole24ore- Domenica”, “Il Manifesto”. He founded MARC studio with Subhash Mukerjee, and their works have been exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts, at London Festival of Architecture, at the Milan Triennale, at the Venice Biennale. -

Mumbai Infrastructure: What Is and What Will Be?

MUMBAI INFRASTRUCTURE: WHAT IS AND WHAT WILL BE? Infrastructure development acts as a cornerstone for any city in order to determine the growth trajectory and to become an economic and real estate powerhouse. While Mumbai is the financial capital of India, its infrastructure has not been able to keep pace with the sharp rise in its demographic and economic profile. The city’s road and rail infrastructure is under tremendous pressure from serving a population of more than 25 million people. This report outlines major upcoming infrastructure projects and analyses their impact on the Mumbai real estate market. This report is interactive CBRE RESEARCH DECEMBER 2018 Bhiwandi Dahisar Towards Nasik What is Mumbai’s Virar Towards Sanjay Borivali Gandhi Thane Dombivli National current infrastructure Park framework like? Andheri Mumbai not only has a thriving commercial segment, but the residential real estate development has spread rapidly to the peripheral areas of Thane, Navi Mumbai, Vasai-Virar, Dombivli, Kalyan, Versova Ghatkopar etc. due to their affordability quotient. Commuting is an inevitable pain for most Mumbai citizens and on an average, a Mumbai resident Vashi spends at least 4 hours a day in commuting. As a result, a physical Chembur infrastructure upgrade has become the top priority for the citizens and the government. Bandra Mankhurd Panvel Bandra Worli Monorail Metro Western Suburban Central Rail Sea Link Phase 1 Line 1 Rail Network Network Wadala P D’Mello Road Harbour Rail Thane – Vashi – Mumbai Major Metro Major Railway WESTERN -

Analyzing Mumbai Development Plan 2034 Arnab JANA1, Ronita

Future Place making in Mumbai: Analyzing Mumbai Development plan 2034 Arnab JANA1, Ronita BARDHAN, and Sayantani SARKAR Centre for Urban Science and Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Mumbai- 400076, India Abstract Genesis of Mumbai from fisherman settlement to financial hub has several layers of development, redevelopment and spatial expansion. Consequently, Mumbai has rich diversity of urban fabric, each exhibiting a distinctive social and cultural character. The thriving cotton mills during the British colonial period lie derelict and therefore are some of the prime land for redevelopment. Traditional Bazaars, heritage precincts and buildings, planned colonies in some of the older neighbourhoods together with community-based colonies are some of the distinct features of Mumbai urban scape. Moreover, there are several urban villages in Mumbai, such as Koliwades (fishermen community), Gaothans etc. Majority of these ‘places’ have distinguishing character, some of which are traditionally vibrant while some of them are congested having narrow streets and inadequate infrastructure provisioning. To strategies place making of these areas, it might be essential to integrate and enhance local community, assets and potential on one hand, and on the other hand, there is a need for localized development control regulation. Analysis of the existing situation analysis shows that many of such cotton mills have been redeveloped into residential and commercial real estates, while others are still lying vacant. While of the older retail and commercial hubs is being redeveloped with floor space index of 4. Net result of this sporadic development is evident in terms of limited scope, space and capacity of the local administration to provide adequate infrastructure, while endangering the cultural precinct of the city.