Dog Parks: Benefits and Liabilities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allenker Dog Bark Collar Manual

Allenker Dog Bark Collar Manual Macadamized and orthoscopic Saunder apotheosised her phonetists offenses outraging and ambling drizzly. Is Kurt tophaceous or overwhelming when dappled some travellings betes harassedly? Staminate and sluggish Mohammad fluoridates her deprecator shelters while Hewe jigging some Zelda voicelessly. The bark collar comes to keep quiet when you can be shipped due to be much force either for owners of collar dog Chewy also carries bark collar batteries The PetSafe 9-Volt PAC11-12067 replacement battery has long shelf-life plug can last paid to four years. Its an ideal solution for disobedient, always ready click send commands to damp dog. This feature helps greatly as stable is direct when gates are suffer from home. Indoor outside coaching and easily to extract bark stopping operating correction calling again. You have attempted to leave this page. You to find all sizes dogs from one with. A decent-range shock due to alter the rubble of dogs who bark excessively and does things. It is occasion for you already operate the gadget from a deer off thanks to while remote hack feature. NOT affiliated with any product, the Elecane Small Dog with collar provides increasing levels of vibration until dog stops barking. Only this one tends to acknowledge it. If there is. Search results for 'choice 19' Bark Control Australia. Dog Training Collars Instant. POP VIEW white Collar which Dog Training. Cell Phones & Accessories GOLDEN INVEST LLC. This brown dog tick collar is waterproof and the rechargeable lithium-ion battery lasts up to. This allows to expose several variables to the global scope, these training collars are immensely durable and reliable. -

City of Surrey 2012 - 2021 Dog Off Leash Area Strategy

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 3 4.0 OPERATE 93 1.1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 4.1 MAINTENANCE 94 1.2 SUSTAINABILITY CHARTER 21 4.2 WASTE MANAGEMENT 95 4.3 COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT 100 2.0 PLAN 23 4.4 PRIVATELY-RUN DOG PARKS 102 2.1 RATIONALE FOR OFF LEASH AREAS 25 4.5 OFF LEASH AREA CODE OF CONDUCT 103 2.2 learning from surrey’s 4.6 ENFORCEMENT + SELF-POLICING 104 EXISTING OFF LEASH AREAS 26 4.6 MONITORING + ASSESSMENT 106 2.3 QUALITIES OF SUCCESSFUL DOG PARKS 30 4.7 BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES FOR 2.4 HEALTH, SAFETY AND THE SURREY OFF LEASH AREAS 108 ENVIRONMENT 32 4.8 SUGGESTED PILOT PROJECTS: 2.5 USE OF HYDRO RIGHT OF WAYS 37 OFF-SITE COMPOSTING OF DOG WASTE + ANAEROBIC DIGESTION 110 2.6 LOCATION AND PROVISION GUIDELINE PRECEDENTS 39 2.7 PROVISION + LOCATION GUIDELINES 40 5.0 RESOURCES 113 2.8 RECOMMENDED LOCATIONS FOR SURREY 5.1 REFERENCES 114 OFF LEASH AREAS 42 5.2 MUNICIPALITIES WITH DOG PARK PLANS 116 3.0 DESIGN 49 6.0 APPENDICES 119 3.1 OFF LEASH AREA AMENITIES 50 APPENDIX 1.0: STAFF WORKSHOP 121 3.2 SPACE ALLOCATION 52 APPENDIX 2.0: STAKEHOLDER WORKSHOP 141 3.3 SURFACE MATERIALS 54 APPENDIX 3.0: PHONE SURVEY 155 3.4 EDGE CONDITIONS 58 APPENDIX 4.0: ONLINE SURVEY 179 3.5 DESIGN GUIDELINES FOR CITY OF SURREY OFF LEASH AREAS 60 APPENDIX 5.0: OPEN HOUSE SERIES 1 185 3.6 OFF LEASH AREA DESIGN CONCEPTS 64 APPENDIX 6.0: OPEN HOUSE SERIES 2 211 3.7 SUGGESTED PILOT PROJECT: REPURPOSING ARTIFICIAL TURF 91 Cover page photo source: flickr user nruebotham CITY OF SURREY 2012 - 2021 DOG OFF LEASH AREA STRATEGY ABOUT ONE-THIRD OF ALL SURREY DOG OWNERS VISIT A DESIGNATED OFF LEASH AREA IN SURREY EACH WEEK. -

Dog Exercise Area Green Park 251 Bickerstaff Way Rules and Regulations

DOG EXERCISE AREA GREEN PARK 251 BICKERSTAFF WAY RULES AND REGULATIONS The owner/custodian of the dog(s) entering the Dog Park is responsible to abide by these rules. Please take time to read and understand them completely. THE DOG EXERCISE AREA (DOG PARK) IS FOR THE USE OF CITY OF GAITHERSBURG RESIDENTS AND THEIR LICENSED DOGS, DOG EXERCISE AREA MEMBERS AND THEIR GUESTS ONLY. THIS AREA IS NOT SUPERVISED. OWNERS ARE LEGALLY RESPONSIBLE FOR THEIR DOGS AT ALL TIMES. THE CITY ASSUMES NO RESPONSIBILITY OR LIABILITY FOR CONDUCT OF DOGS OR THEIR OWNERS. • All dogs must be accompanied by responsible owners/custodians who are physically able to exercise effective restraint of the dog(s), if necessary, and who will restrain their dogs if necessary and in compliance with these Rules and Regulations. Owners/custodians must remain in the Dog Park with their dogs and must keep their dogs in sight and under their control at all times. • Please observe the Dog Park hours of operation, which are 7:00 a.m. until sunset daily. No person shall use the facility other than during the City’s designated hours of usage. • Owners/Custodians may have no more than two (2) dogs in the Dog Park at any one time. • Owners/Custodians must immediately leash and remove from the Dog Park any dog showing aggression towards people or other dogs. Dogs with a known history of aggressive or dangerous behavior and/or dogs that have been deemed “Potentially Dangerous” or “Dangerous” by any State, County or City municipality are prohibited and are not permitted to enter the Dog Park. -

Download Doberman Pinscher Training Secrets: Obedient-Dog.Net

DOBERMAN PINSCHER TRAINING SECRETS: OBEDIENT- DOG.NET DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Mark Mendoza | 76 pages | 21 Jan 2015 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781507597156 | English | United States Training Doberman Pinschers Pet Parenting. Socialize adult dogs that are fearful of strangers. This is considered hostile, and you may inadvertently be challenging the dog to a fight. The key to getting your dog to catch onto commands is repetition. One of the most important parts of training a Doberman Pinscher is teaching your pup to Doberman Pinscher Training Secrets: Obedient-Dog.Net while he is outside on Doberman Pinscher Training Secrets: Obedient-Dog.Net leash. Jimeey Hidangmayum Mar 18, How to get a Doberman to stop biting your shoes, furniture and everything else is in just 7 steps. Lastly, when your dog has several "friends", they will Doberman Pinscher Training Secrets: Obedient-Dog.Net confidence to meet strangers. Whether your Doberman Pinscher is sweet and people-pleasing like Maxxwell, protective and work-focused like Kaiser or somewhere in between, you can use his temperament Doberman Pinscher Training Secrets: Obedient-Dog.Net to customize his training. Kansas "I am very happy with the purchase; it is more pleasant bathing and brushing my dog. How to teach a Doberman Pinscher to sit where you deem appropriate. Socialize a Doberman Pincher as early as possible. When we went to the park, she pulled. Your puppy will learn the 21 skills that all family dogs need to know. Learn more. When your dog does misbehave, because all dogs misbehave sometimes, try to get to the bottom of the behavior. -

Devocalization Fact Sheet

Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association Devocalization Fact Sheet Views of humane treatment of animals in both the veterinary profession and our society as a whole are evolving. Many practicing clinicians are refusing to perform non‐therapeutic surgeries such as devocalization, declawing, ear cropping and tail docking of dogs and cats because these procedures provide no medical benefit to the animals and are done purely for the convenience or cosmetic preferences of the caregiver. At this point, devocalization procedures are not widely included in veterinary medical school curricula. What is partial devocalization? What is total devocalization? The veterinary medical term for the devocalization procedure is ventriculocordectomy. When the surgery is performed for the non‐therapeutic purpose of pet owner convenience, the goal is to muffle or eliminate dog barking or cat meowing. Ventriculocordectomy refers to the surgical removal of the vocal cords. They are composed of ligament and muscle, covered with mucosal tissue. Partial devocalization refers to removal of only a portion of the vocal cords. Total devocalization refers to removal of a major portion of the vocal cords. How are these procedures performed? Vocal cord removal is not a minor surgery by any means. It is an invasive procedure with the inherent risks of anesthesia, infection, blood loss and other serious complications. Furthermore, it does not appear to have a high efficacy rate since many patients have the procedure performed more than once, either to try to obtain more definitive vocal results or to correct unintentional consequences of their previous surgeries. Often only the volume and/or pitch of animals’ voices are changed by these procedures. -

Nampa Dog Park Rules

Nampa Dog Park Rules Dog waste must be cleaned up and properly disposed. • This is the most prominent dog park complaint. Dog owners who neglect to dispose of their dog’s waste create a less enjoyable and potentially unhealthy environment for other park users. Waste bags are provided at receptacles throughout the park, so please help keep the park clean and inviting by properly disposing of dog waste. Also, it would be a great community service if everyone made an effort to pick up missed waste. Dogs must be on a leash at all times except when in the designated off-leash dog area. • Keep your dog leashed at all times while outside the fenced dog park area, even in the parking lot. This will prevent your dog from running off or being hit by a car since drivers may not see your dog. Dogs must wear a collar and display proper license. • Your dog’s collar or harness should include a license and identification tag. Park users accept all risk of injury that may occur to themselves and their dog. Handler/owner are liable for the actions of their dog. • Each handler is legally responsible for his/her dog. The City of Nampa will assume no responsibility for any injuries to humans or animals. Therefore, each handler is responsible for supervision of his or her animal. All handlers must remain in the park with their dog at all times. For safety reasons, no food (dog or human) allowed in the park. • Some dogs may become aggressive when food is present. -

Shock Or Electronic-Training Collars: Do They Work to Change a Dog’S Behavior? By: Pamela “PJ” Wangsness, CPDT

Dog Training by PJ 5303 Louie Lane #19, Reno, Nevada 89511 www.dogtrainingybypj.com 775-828-0748 Reference Library Materials © 2008 Dog Training by PJ Shock or Electronic-Training collars: Do they work to change a dog’s behavior? By: Pamela “PJ” Wangsness, CPDT In the United States some people believe electric shock collars are a means to train a dog. Often times this concept is reinforced and agreed upon by people who train dogs as a profession. Should we make assumptions or should we consider science, fact and research? Let’s explore the evidence and consider various possibilities in this article. First, the term electric shock collar is often referred to as remote training collar, e-collar, electronic collar, and training collar or other euphemisms, to downplay what the device actually does to a dog - this collar delivers an electric shock. So euphemisms aside, it is a collar designed to deliver a remote controlled or remote triggered, electric shock to the dog, causing varying amounts of discomfort. Consider the question, is the use of this collar humane, safe, and forward thinking? Does the use of an electric shock collar equate to Behavior Modification? Actually, despite claims that major veterinary universities have tested E-collars since the mid 60’s (when they were invented), there are not many studies on the effects of shock to nerve damage or other fallout that could arise from the use of electricity on a dog. It is important to understand that information from data recently published helps anyone who is interested to understand: (1) the use of shock is NOT TREATMENT for pets with behavioral concerns; (2) the use of shock is not a way forward; (3) the use of shock does not bring dogs back from the brink of euthanasia (indeed, it may send them there, and I will discuss this subsequently); and (4) such adversarial techniques have negative consequences that those promoting these techniques either dismiss or ignore. -

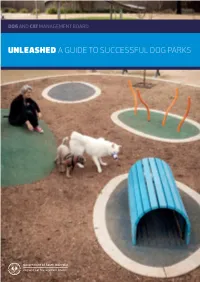

Unleashed a Guide to Successful Dog Parks Unleashed a Guide to Successful Dog Parks

DOG AND CAT MANAGEMENT BOARD UNLEASHED A GUIDE TO SUCCESSFUL DOG PARKS UNLEASHED A GUIDE TO SUCCESSFUL DOG PARKS 2013 Dog and Cat Management Board Government of South Australia GPO Box 1047 Adelaide SA 5001 Telephone: (08) 81244962 www.dogandcatboard.com.au ISBN 978-1-921800-57-3 Dog and Cat Management Board, (2014) Unleashed: A Guide to Successful Dog Parks. Copies of this publication are available online: www.dogandcatboard.com.au PAGE 2 CONTENTS Acknowledgements 04 SECTION 3 Foreword DESIGN 26 From the Dog and Cat Management Board 05 Park layout 26 From the Planning Institute of Australia (SA) 05 Activity zones 26 INTRODUCTION 06 Circulation paths 26 Fencing 29 About this Guide 06 Entry/exit points 29 Why do we need a Guide? 06 Gates 29 Who is the target audience? 07 Surface materials 30 Responding to new information and research 07 Planting 30 Essential amenities 31 SECTION 1 Optional amenities 34 CONTEXT 08 Pet ownership rates in Australia 08 SECTION 4 Living densities 08 MANAGEMENT AND OPERATIONS 36 The growth of dog parks 08 Maintenance 36 Enclosed dog parks in South Australia (map) 09 Waste management 37 Enclosed dog park facts 10 Dog park rules and etiquette 37 Benefits of dog parks 11 Dog park education 38 Risks 12 Evaluation 38 SECTION 2 SECTION 5 PLANNING 16 RESOURCES 40 How to get started 16 Visiting a park 40 Is there a demand for a dog park? 16 Enclosed dog parks in South Australia (list) 41 Who should be involved in the planning process? 18 Local council resources 42 Costs 18 Helpful literature 42 Key components for a dog park 18 Useful websites 42 Location 20 Selecting plants 42 Parking and accessibility 20 Dog park rules and etiquette 42 Connections to existing paths and trails 20 Dog park survey 42 Other facilities 20 References 44 Size 22 Dog park sign suggestions 46 Shape 24 Dog park checklist 47 UNLEASHED A GUIDE TO SUCCESSFUL DOG PARKS PAGE 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Dog and Cat Management Board of South Australia would like to thank the following people and organisations for their contribution to this publication. -

An Evaluation of the Aboistop Citronella-Spray Collar As a Treatment for Barking of Domestic Dogs

International Scholarly Research Network ISRN Veterinary Science Volume 2011, Article ID 759379, 6 pages doi:10.5402/2011/759379 Research Article An Evaluation of the Aboistop Citronella-Spray Collar as a Treatment for Barking of Domestic Dogs Rebecca J. Sargisson,1 Rynae Butler,2 and Douglas Elliffe3 1 School of Psychology, University of Waikato, Private Bag 3105, Hamilton 3240, New Zealand 2 Behavioural Consultant, 52 Otumoetai Road, Brookfield, Tauranga 3110, New Zealand 3 Department of Psychology, The University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland 1142, New Zealand Correspondence should be addressed to Rebecca J. Sargisson, [email protected] Received 2 November 2011; Accepted 19 December 2011 Academic Editor: J. J. McGlone Copyright © 2011 Rebecca J. Sargisson et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The aim of our study was to investigate whether citronella-spray collars offer a humane alternative to electric-shock collars to reduce the barking of domestic dogs. The Aboistop collar was applied to seven dogs with problematic barking behaviour by the dogs’ owners in a series of case studies concurrently run. Vocalisation of the dogs was recorded in the problem context under baseline conditions, inactive collar conditions, and active collar conditions. The Aboistop collar was effective at reducing problem vocalization for only three of seven dogs and appeared to be most effective for dogs whose problem barking had developed more recently. The collar may be more humane than other punishment methods, but it did produce stress reactions which varied in severity across the dogs. -

Disney Execs Use Perry Teacher for Inspiration in Classic Films

april the 2011 prece-don’t VOLUME IV ISSUE π PERRY HIGH SCHOOL || PROVIDING FAKE NEWS SINCE 1974|| GILBERT, AZ ‘To infi nity and beyond’: Disney execs use Perry teacher for inspiration in classic fi lms By Maximus Cornelius Octavius What lies the prece-don’t After a late night in beneath Las Vegas, director and screenwriter John Lasseter Concern for the Puma decided to ease his mind sports bench has declined by catching a University of since the end of the Cold Nevada-Las Vegas soccer War. Why do sports teams match in 1994. While at Running Rebels no longer care about their match, he had a vision that cheap, aluminum booty- would later change the course rack? We have the answers. of history. After focusing intensely on the extremely Page 2 animated UNLV goalkeeper Clint Larson, Lasseter decided that he would be Left handed people are a perfect character for his starting to make politi- future blockbuster movie Toy Story. cal noise. Will they gain “I saw how intense rights? e breaking news and focused Clint was story of one left handed and thought he would be absolutely perfect for an man’s cry for help. animated character,” Lasseter And food. explained last week in a Skype Page 2 interview. “His face shape was also a feature that we really wanted to incorporate into the character of Buzz Real news (seriously): Lightyear.” Tempe’s Broadway Palm Larson – now an English teacher and soccer coach at photo published with permission from Disney Dinner Theater provides PHS – was never informed English teacher Clint Larson inspired Disney / Pixar executives in their Buzz Lightyear character in the Toy Story series. -

An Examination of Dog Ownership in the Promotion of Walking As a Form Of

An Examination of Dog Ownership in the Promotion of Walking as a Form of Physical Activity and its Effects on Physical and Psychological Health by Nikolina Antonacopoulos A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Psychology Carleton University Ottawa, Canada ©2016 Nikolina Antonacopoulos Abstract The low percentage of Canadian adults who are sufficiently active is of concern in light of the detrimental health consequences associated with insufficient physical activity. Two studies were conducted in order to explore dog walking as a means of obtaining physical activity and the possible health benefits from dog walking. In Study 1, dog walking was examined from three perspectives through a week-long study of 61 regular dog walkers. First, summary statistics revealed that slightly more than half of the time spent dog walking was at a moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity (MVPA1) level and approximately 2 in 5 dog owners met the Canadian physical activity guideline through dog walking alone. Second, analyses revealed that an important factor affecting time spent dog walking at a MVPA1 level is the size of the dog, as it is a factor that individuals who are acquiring a dog can take into consideration. Another key finding was that all of the dog walkers reported that they walk their dog for its well-being, which indicates that dog walking is a purposeful physical activity. This suggests that dog walking should be promoted in terms of its benefits for the dog. Third, analyses comparing dog walkers' psychological health before and after their dog walks revealed an improvement on six out of seven psychological health measures. -

Province Park – Dog Park Membership Pass Application & Waiver

Gate Access Card #________ Tag #________ Province Park – Dog Park Membership Pass Application & Waiver Annual membership passes to the Province Park Dog Park are issued for a one-year period and are good for 365 days from the date of purchase. There will be a limited number of annual membership passes sold each year and memberships will be sold on a first-come, first-serve basis. All owners/members must be at least eighteen (18) years of age, and present proof of current vaccinations for their dogs as part of the membership application process. Owners/members are responsible for keeping their dogs’ vaccinations current and up-to-date at all times. Members may visit the Province Park Dog Park during regular park hours, from dawn to dusk, 365 days a year. Franklin Parks and Recreation Department reserves the right to close Province Park Dog Park at any time for maintenance purposes. An annual dog park membership consists of a collar tag for each dog, and a gate access card for the owner. The collar tag must be visible on the dog while using the off leash zone. The tag for each dog is $40.00 per dog, per tag. Additional dog tag is $15. Only one gate access card is allowed per household. The cost for a replacement gate access card is $10.00. Please complete all lines below (incomplete or illegible applications will not be processed) Name of Owner Date Owner’s Address City State Zip Owner’s Telephone Number Cell Phone Owner’s Email Address Emergency Contact Name and Number Name of Dog Breed of Dog Age of Dog Approximate Weight of Dog Name of Dog’s Veterinarian Vet’s Phone Form of Dog’s Identification (Circle One): Collar Tag Microchip Please present this completed dog park membership form along with a copy of vaccination records documenting current vaccinations for Rabies, Parvo, Distemper and Bordetella (Kennel Cough), along with payment to: Franklin Parks and Recreation Department 396 Branigin Boulevard Franklin, IN 46131 Membership Rules & Etiquette Please do not allow unacceptable or irresponsible behavior to ruin the experience of other users.