Vivian Maier the Color Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The President's Corner 1

VOLUME 41 NUMBER 2 JAN-MAR 2015 The President’s Corner vision, craftsmanship, and art, have influ‐ enced the photography of many of us at the Thinking About club and across the photosphere. Spring, (continued on next page) Influencers, and Gestures By David Marshak In This Issue page As we all try to The President's Corner 1 endure this end‐ by Dave Marshak less winter (and SW Trek II 3 wish we were in Florida with our esteemed by Joe Kennedy treasurer), my thoughts turn to spring. Results of the Newsletter Survey 7 by Ellen Berenson I am thinking of a spring that will not only be the end of winter, but also the calling of New Member Interviews 9 new photo opportunities that will get us out by Janet Casey of the house and back in the woods, by the Reflections on Vivian Maier 11 shore, or on the street. by Deb Maynard Exploring Portrait Photography 12 For SBCC, spring will bring an exciting set of by Orin Siliya guest speakers including three who have SBCC Holiday Banquet 16 presented to us multiple times before – Ron by Kirsten Torkelson Rosenstock, Joe LeFevre, and Mark Bowie – SBCC Programming: What's Next? 19 and whom I personally have seen speak in other venues many times. It is exactly for by Janet Casey the same reason that I’ve seen them before Meeting Schedule 27 that I am very excited to see them again. It’s List of Club Officers and Committees 28 because I put them in the category of Influ‐ encers—people who, with their unique (continued from previous page) Gesture makes the photo interesting. -

Vivian Maier: a Photographer Found Free Ebook

FREEVIVIAN MAIER: A PHOTOGRAPHER FOUND EBOOK John Maloof,Howard Greenberg,Marvin Heiferman,Laura Lippman | 288 pages | 20 Nov 2014 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780062305534 | English | New York, United States About Vivian Maier Vivian Dorothy Maier was an American street photographer whose work was discovered and recognized after her death. She worked for about 40 years as a nanny, mostly in Chicago's North Shore, while pursuing photography. She took more than , photographs during her lifetime, primarily of the people and architecture of Chicago, New York City, and Los Angeles, although she also traveled and photographed worldwide. During her lifetime, Maier's photographs were unknown and unpublished; many of her. This month, Vivian Maier: A Photographer Found will be published— the largest collection of her work to date. On October 30, a new exhibit of her photographs will open at the Howard Greenberg. John Maloof, who bought most of it, put up a selection of scans on a website, which immediately went viral; Maier posthumously became a media sensation. Maloof’s VIVIAN MAIER: A Photographer Found. Photography This was created in dedication to the photographer Vivian Maier, a street photographer from the s - s. Vivian's work was discovered at an auction here in Chicago where she resided most of her life. Often regarded as the Emily Dickinson of photography – since united by the same reticence in life and posthumous popularity as the American poetess – Vivian Maier was a street photographer before this term was even coined and has today secured her place in photography’s pantheon. Information about the discovery of Vivian Maier's photographs at an auction in Chicago and how research about her was conducted. -

VIVIAN MAIER: out of the SHADOWS Kill Date – March 23

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE VIVIAN MAIER: OUT OF THE SHADOWS Kill Date – March 23 Exhibition Title: Vivian Maier: Out of the Shadows Exhibition Dates: February 1 - March 23, 2013 Opening Reception: Friday, February 15, 6-8PM for immediate release Gallery Hours: Monday - Thursday 11 am – 10 pm, Friday – Sunday 12 pm – 8 pm VIVIAN MAIER: Location: Photo Center NW, 900 12th Avenue, Seattle, 98122 OUT OF THE SHADOWS More info & images: Erin Spencer, [email protected], 206.720.7222 Lecture & Book Signing: Richard Cahan, co-author of Vivian Maier: Out of the Shadows February 8, 6:30 pm @ Photo Center NW CONTACt RAFAEL SOLDI The Photo Center NW is proud to present Vivian Maier: Out of the Shadows, an Marketing Director exhibition of photographs by Vivian Maier (1926-2009) from the Jeffrey Goldstein collection. This exhibition of posthumous silver gelatin prints puts Maier’s work in Phone the context of her life during her highly creative period from the 1950s through the 206.720.7222 x20 1970s. This is the first time Maier’s impressive body of work and unique story will e-mail be shared in Seattle. [email protected] online Maier’s work was discovered in Chicago in 2007 when boxes of abandoned prints, www.pcnw.org negatives and undeveloped film were sold at auction. Born in New York, Maier spent much of her youth in France. Starting in the late 1940s, she shot an average of a roll of film a day. She moved to Chicago in the mid-1950s, and spent the next 40 years Photo Center northwest working as a nanny to support her passion for photography. -

F14 US Catalogue.Pdf

HARPERAUDIO You Are Not Special CD ...And Other Encouragements Jr. McCullough, David Summary A profound expansion of David McCullough, Jr.’s popular commencement speech—a call to arms against a prevailing, narrow, conception of success viewed by millions on YouTube—You Are (Not) Special is a love letter to students and parents as well as a guide to a truly fulfilling, happy life Children today, says David McCullough—high school English teacher, father of four, and HarperAudio 9780062338280 son and namesake of the famous historian—are being encouraged to sacrifice On Sale Date: 4/22/14 passionate engagement with life for specious notions of success. The intense pressure $43.50 Can. to excel discourages kids from taking chances, failing, and learning empathy and self CDAudio confidence from those failures. Carton Qty: 20 Announced 1st Print: 5K In You Are (Not) Special, McCullough elaborates on his nowfamous speech exploring Family & Relationships / how, for what purpose, and for whose sake, we’re raising our kids. With wry, Parenting affectionate humor, McCullough takes on hovering parents, ineffectual schools, FAM034000 professional college prep, electronic distractions, club sports, and generally the 6.340 oz Wt 180g Wt manifestations, and the applications and consequences of privilege. By acknowledging that the world is indifferent to them, McCullough takes pressure off of students to be extraordinary achievers and instead exhorts them to roll up their sleeves and do something useful with their advantages. Author Bio David McCullough started teaching English in 1986. He has appeared on and/or done interviews for the following outlets: Fox 25 News, CNN, NBC Nightly News, CBS This Morning, NPR’s All Things Considered, ABC News, Boston Herald, Boston Globe, Wellesley Townsman, Montreal radio, Vancouver radio, Madison, WI, radio, Time Magazine and Epoca (Brazilian magazine). -

Finding Vivian Maier Discussion Guide

www.influencefilmclub.com Finding Vivian Maier Discussion Guide Directors: John Maloof, Charlie Siskel Year: 2014 Time: 83 min You might know this director from: FINDING VIVIAN MAIER is the first feature-length film from these directors. FILM SUMMARY Mysterious, eccentric, caring, cruel, paranoid, reclusive, loner, pack rat, spinster. Viv, Vivian, Miss Maier, Mrs. Mayers. The elusive Vivian Maier went by many names. She was many things to many people. Attempting to comprehend who this prolific street photographer really was, FINDING VIVIAN MAIER reaches out to the many lives Vivian touched. Where did she come from and what drove her to create so much, and yet reveal so little? After discovering Vivian’s work at a Chicago auction house, historian and director John Maloof became determined to uncover the tale of this woman who touched so many lives but disclosed so little of her own. Through interviews with her employers and an extensive treasure hunt which took him from a tiny village in the French Alps to Southampton, New York and all across the greater Chicago area, Maloof pieces together the puzzle of Vivian’s creative, solitary life. As he develops her unexposed negatives and exhibits her art, the extent of Vivian’s previously unknown life unfolds in full color. A tale of opposites, FINDING VIVIAN MAIER dares to open a Pandora’s box to those who lived with her, while unveiling extensive imagery of the world between the 1950s and early 2000s. Ultimately, the film reveals the true story of one woman’s quest to capture the dark side of existence and to expose the stories of the downtrodden while living under the roof of the well-to-do. -

Exhibit Unearths Long-Long Photos by Vivian Maier

Exhibit unearths long-long photos by Vivian Maier Alex Taylor | Contributor Oct 15, 2014 Alex Taylor | Contributor “A Quiet Pursuit” is an appropriate title for the new exhibit displaying almost 100,000 negatives from an American photographer’s work, which spanned over 50 years and waited silently in storage facilities for years until they were discovered and developed. As a part of the FotoFocus 2014 Biennial event, Vivian Maier’s long-lost photography is being displayed at 1400 Elm Street at Washington Park from Sept. 26 to Nov. 1. In 2007, historian John Maloof brought Maier’s photos out from the files and into galleries. Maier, who died in 2009 at the age of 83, was an American photographer of French and Austrian descent. She lived in New York City then Chicago and worked as a nanny in both cities, but also briefly traveled around the world. Her first camera was a Kodak Brownie box camera that had only one shutter speed and no focus control or aperture dial. Maier eventually graduated to a Rolleiflex camera, in square-medium format, then to a Leica IIIc and various German SLR cameras. For most of her adult life, Maier did not have a dark room or even money to expose her pictures. She would shoot photos that captured herself in reflections, but also captured the people who passed by her. Most of Maier’s’s work is directed to street scenes and portraits of people she never met. Later in her career, Vivian switched to color film and also changed her subject matter. -

PHOTOGRAPHY When Chicago-Based Nanny Vivian Maier Died In

PHOPHOTOGRAPHYTOGRAPHY SSTREETTREET LIFE ORIGINAL EYE Vivian Maier, left, in an undated self-portrait. Most of the photographs here are from the 1950s. Her astonishing portfolio of street portraits covers all ages and classes. One woman’s extraordinary images of ordinary lives he story of Vivian Maier is so It was only when the book was finished a few calls her, “a really, really awesome person to hang portraiture and street life, she covers children, “I hope she’s OK with what I’m doing,” he says. When Chicago-based nanny Vivian Maier died in 2009, she left behind incredible that the man who months later that he looked at the negatives out with if you were a kid. To be honest, I wish she covers abstraction and she does them all “She had no love life, no family and really had discovered her says: “If you again and slowly realised he was in possession she had been my nanny. She would take kids on with a style that I think digests the history of nobody that was close to her. The only thing that 100,000 negatives that no one but she had ever seen. Her work was made this up for Hollywood of something unimaginably precious. He began these wild adventures that only the coolest kids photography.” she had was the freedom of her camera to express it would be like, ‘Oh, come on, printing and posting Maier’s photographs to would think of doing.” She was also, he says, extraordinarily prescient: herself and I think the reason she kept it secret is that’s too hard to believe.’ She a blog (vivianmaier.blogspot.com), which he They had no idea, though, that their nanny “There’s work that reminds me of Diane Arbus, because it’s all she had.” discovered by chance by an estate agent who set about putting her pictures is,” he adds, “the most riveting describes as “a snowball that just started rolling spent her days off taking some of the most for example, but they were done before Diane He adds: “I wish I could go back in time to person I have ever encountered.” and has just been building ever since. -

A Necessary Condition for Photographic Art

VALUE PERSPECTIVE: A NECESSARY CONDITION FOR PHOTOGRAPHIC ART A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Humanities By MICHELLE MARIE BURDINE B.A., Antioch McGregor, 2005 A.A.S., Ohio Institute of Photography, 1995 2013 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL April 25, 2013 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Michelle Marie Burdine ENTITLED Value Perspective: A Necessary Condition for Photographic Art BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Humanities. ________________________________ Donovan Miyasaki, Ph.D. Thesis Director ________________________________ Ava Chamberlain, Ph.D. Director, Masters of Humanities Program Committee on Final Examination ___________________________________ Donovan Miyasaki, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Karla T. Huebner, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Tracy Longley-Cook, MFA ___________________________________ R. William Ayres, Ph.D. Interim Dean, Graduate School ABSTRACT Burdine, Michelle Marie. M.H. Master of Humanities Program, Wright State University, 2013. Value Perspective: A Necessary Condition for Photographic Art. The conjoined relationship photography has with technology complicates conversations about photography as art because this relationship allows photography to be used interchangeably for practical, social, and commercial purposes, as well as for art. A theory of art for photography is needed in order to accurately separate photographic -

Fall 2020 Nonfiction Rights Guide

Fall 2020 Nonfiction Rights Guide 19 West 21st St. Suite 501, New York, NY 10010 / Telephone: (212) 765-6900 / E-mail: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS MEMOIRS & BIOGRAPHIES TONIC HEAD OF THE MOSSAD STORIES I MIGHT REGRET TELLING YOU THE SEEKERS TANAQUIL BLIND AMBITION PLEASE DON’T KILL MY BLACK SON PLEASE NOTHING PERSONAL PROOF OF LIFE MINDFULNESS & SELF-HELP THE SPARE ROOM BRAT HEART BREATH MIND HOUSE OF STICKS HI, JUST A QUICK QUESTION VIVIAN MAIER DEVELOPED BE WATER, MY FRIEND CRYING IN THE BATHROOM MY EVERYTHING I REGRET I AM ABLE TO ATTEND THE SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY OF GROWING YOUNG HOW TO SAY BABYLON THE SECRETS OF SILENCE REBEL TO AMERICA TRUE AGE HORSE GIRLS INTIMACIES KIKI MAN RAY OUTSMART YOUR BRAIN THE BIG HURT THE POWER OF THE DOWNSTATE AUGUST WILSON THE SUM OF TRIFLES NARRATIVE NONFICTION YOU HAD ME AT PET NAT MURDER BOOK THE DOCTOR WHO FOOLED THE WOLRD THE RECKONING THE MISSION GUCCI TO GOATS THE POWER OF STRANGERS RHAPSODY CAN’T KNOCK THE HUSTLE SWOLE CHASING THE THRILL ONBOARDING CURE-ALL CONQUERING ALEXANDER IN THIS PLACE TOGETHER UNTITLED TOM SELLECK MEMOIR SQUIRREL HILL THE GLASS OF FASHION NOSTALGIA DOT DOT DOT PORTRAIT OF AN ARTIST CHANGE BEGINS WITH A QUESTION SPOKEN WORD MUHAMMED THE PROPHET UNFORGETTABLE TABLE OF CONTENTS, CONT. NARRATIVE NONFICTION, CONT. SCIENCE, BUSINESS & CURRENT AFFAIRS TALKING FUNNY 2030 DEMOCRACY’S DATA BREAK IT UP THE KINGDOM OF PREP BATTLE TESTED GOOD COP GOOD COMPANY OSCAR WARS EDITING HUMANITY EDITING AROUND THE CORNER TO AROUND THE WORLD WE DON’T EVEN KNOW YOU ANYMORE BETTING -

Vivian Maier

3-5 Swallow Street, London, W1B 4DE / [email protected] Vivian Maier 04 August - 05 September 2015 Vivian Maier was a professional nanny who, unbe- knownst to those that knew her, used her spare time to scour the streets of Chicago and New York, using her trusty Rolleiflex, to shoot up to a whole roll of film each day. Unknown in her life- time, she left an outstanding body of work com- posed of more than 100,000 negatives and unde- veloped roll films. Self-Portrait, Chicago Area, 1960 Her recent ascent from recluse to revered artist is phenomenal, and has become one of the most remarkable stories in the history of photography. Her photographs show her exceptional eye for detail and flair for composition. They are witty and intelligent, and charged with a strong sense of empathy. She took photographs of the downtrodden as well as the well-heeled, of youth and of age. Maier was endlessly inspired by the lives around her. If it had not been for a chance discovery at a Chicago auction in 2007, the world would still be una- ware of her vast oeuvre and undeniable talent. Maier held the accumulation of her passion for pho- tography in storage lockers, as she had no permanent home of her own. Undeveloped film, negatives and prints from her storage locker were auctioned off when Maier fell on hard times later in her life. John Maloof, an amateur historian, bid blind on a box packed with negatives taken from Maier’s lock- er. What he found inside would change his life, and the history of photography, forever. -

VIVIAN MAIER Self-Portraits

LES DOUCHES LA GALERIE PRESS KIT VIVIAN MAIER Self-Portraits UNTIL JANUARY 30TH, 2021 © Estate of Vivian Maier / Courtesy Maloof Collection; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York & Les Douches la Galerie, Paris Les Douches la Galerie is pleased to present a new selection of self-portraits by Vivian Maier. Produced between 1953 and the 1970s, they once again demonstrate her eye for reflections, her great sense of composition and, more generally, the richness of her work. Les Douches la Galerie 5, rue Legouvé 75010 Paris | lesdoucheslagalerie.com Closed until further notice Self-Portrait: My Impressions of Vivian Maier BY ELIZABETH AVEDON “I have often wondered about the significance of capturing your own likeness, the experience of being represented on both sides of the frame. I have to believe it is more than just vanity or narcissism. One would naively imagine a self-portrait informs us about the person. We observe the figure illustrated, and in the gaze back we believe we can determine something about their life, their work, their day. Searching for expression we discern clothes, choices, surroundings – all in an effort to resolve the mystery of self. I am not sure if we can read the « self » in Vivian Maier’s self-portraiture or even chart the progression of her life through their images. We look at her self-portraits for revelations, but she does not really give us much. She is alone in her reflections. Her viewpoint difficult to judge. No hint of emotion or reaction. Never a portrait with a partner. She is seldom with a friend, occasionally with a child. -

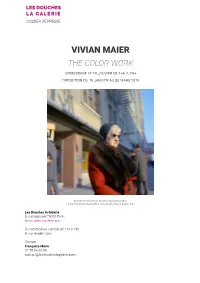

Vivian Maier the Color Work

LES DOUCHES LA GALERIE DOSSIER DE PRESSE VIVIAN MAIER THE COLOR WORK VERNISSAGE LE 19 JANVIER DE 14H À 19H EXPOSITION DU 19 JANVIER AU 30 MARS 2019 ©Estate of Vivian Maier, Courtesy Maloof Collection; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York; Les Douches la Galerie, Paris Les Douches la Galerie 5, rue Legouvé 75010 Paris lesdoucheslagalerie.com Du mercredi au samedi, de 14h à 19h et sur rendez-vous Contact : Françoise Morin 01 78 94 03 00 [email protected] VIVIAN MAIER, THE COLOR WORK Un des préceptes incontournables de la photographie veut que les meilleurs photographes de rue soient ceux qui ont appris à être invisibles, ou du moins, à se convaincre qu’ils le sont. Au fil des années, j’ai arpenté les rues aux côtés de Cartier-Bresson, Garry Winogrand, Tony Ray-Jones, Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, Tod Papageorge, ainsi que de quelques artistes de la jeune génération – Gus Powell, Mela- nie Einzig, Ben Ingham et Matt Stuart –, et chacun de nous a un petit numéro bien rodé pour travailler dans la rue. Esquives, feintes, pirouettes, c’est en se faufilant, le regard aux aguets, que l’on traverse les foules ou les manifestations, les avenues et les ruelles, les parcs et les plages, tous les lieux où la vie ordinaire attire notre attention et notre désir. C’est notre invisibilité qui nous permet de dérober impu- nément le feu des dieux. En 2009, c’est sans crier gare que la tornade Vivian Maier est entrée dans l’histoire déjà très riche de la photographie de rue. En octobre de cette année-là, j’ai reçu un e-mail de John Maloof, un jeune artiste que je ne connaissais pas.