Why Grand Juries Do Not (And Cannot) Protect the Accused Andrew D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current, January 19, 1984

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Current (1980s) Student Newspapers 1-19-1984 Current, January 19, 1984 University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/current1980s Recommended Citation University of Missouri-St. Louis, "Current, January 19, 1984" (1984). Current (1980s). 113. https://irl.umsl.edu/current1980s/113 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Current (1980s) by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. January 19, 1 ~84 University of Missouri-St. Louis Issue 470 Degrees conferred on 603 students Olson's remarks to the near stu'dents are shouldering a larger "What is most important for in scholastic societies. Kevin A. Curtin editor capacity crowd at the gym part of the financial burden than the people of Missouri is that we Speaking directly to tile nasium offered both a reflection ever. In 1963, fees were $100 per take affirmative steps to ensut:e graduates, Olson praised their Celebrating its 20th birthday, of the past 20 years and also a semester. Nciw they are in excess we retain the quality of indi successes and reminded them of UMSL graduated 603 students message to Missouri citizens not of $600. viduals that have been so pains their personal and social from its ranks during to abandon higher education in "Some say that is as it should takingly recruited," Olson said. res·ponsibilities. ceremonies held Jan. 8 at the the future. -

Buried Treasure

THE DETROIT CONTINUING THE STRUGGLE FOR JUSTICE A N C 0 N T INSIDE NEWS Young musicians will call for an end to vio lence at today's Hip- Hop Peace Summit in Detroit. Page 5. SPORTS Even with a good year from Steve Yzerman, below, it won't be last season all over again. Without Konsantinov and Vernon, a Stanley Cup for the Red Wings is unlikely. Back Page. Journal photo by GEORGE WALDMAN Point RosaMarsh at Metro Beach, one of the state’s most popular bird-watching spots, is threatened by encroaching development. Meanwhile, an Ann Arbor group creates a wetland. Story, Page 3. Buried treasure Metropark marshwatchers see troubleon drawing board Journal photo by COOK By Robin Fornoff That it remains intact is a testa of stalwarts fear the marsh is dying Journal Staff Writer ment to the endurance of nature. Itand is a new park development may INDEX On this warm and bright autumnsurrounded by illegal fill, huge chunksobliterate one of the last remnants of morning there are dozens of woodof concrete, scrap wood and othercoastal marsh on the Michigan side of Between the Lines Page 12 ducks prattling near a long-dead trashtree dumped by park employees atLake a St. Clair. The park authority Classifieds Page 28 trunk and a blue-winged teal skimstime wetlands were considered and Michigan’s Department of the water’s surface in a silent landing.swamps that needed to be filled, levNatural Resources plan to build a Crossword Page 29 Last fall Fred Charbonneau ofeled and paved. boat launch within 50 feet of the Editorials Page 10 Warren counted 300 loons here, a birdThe marsh has survived years ofmarsh. -

Layout 1 (Page 2)

AUGUST 12-18, 2011 CURRENTSURRENTS CThe News-Review’s guide to arts, entertainment and television TURBULENT TROUBADOUR Roseburg musician brings Texas-style blues to show Saturday MICHAEL SULLIVAN/The News-Review INSIDE: What’s Happening/3 Calendar/4 Galleries/6 Book Review/10 TV/15 Page 2, The News-Review Roseburg, Oregon, Currents—Thursday, August 11, 2011 * &YJUt$BOZPOWJMMF 03t*OGPt3FTtTFWFOGFBUIFSTDPN Roseburg, Oregon, Currents—Thursday, August 11, 2011 The News-Review, Page 3 what’s HAPPENING ROSEBURG tonight, blues artists Buddy Guy and Jimmie Vaughan Fri- Optimist hosts FOUR-SQUEAL DRIVE day and tribute band Beatle- Mania Live! Saturday. Con- band fundraiser certs on the Umpqua Park The Roseburg Optimist Club stage start at 8 p.m. each night. hosts its Battle of the Bands Daily, 4-H and FFA events fundraiser from 6 to 10 p.m. begin at 9 a.m., carnival gates Saturday at Pyrenees Vineyard open from 10 a.m. to 11 p.m. and Cellars, north location, daily, exhibit buildings open 707 Hess Lane, Roseburg. 11 a.m. to 11 p.m. Local musi- Music entertainment cal acts happen throughout the includes Not Penny’s Boat, day on the Charter Communi- The Dixonville Chicks and cations Stage. Dylan James. Reserved seating for con- Advance tickets are $20 certs is extra and tickets are each or $35 for a couple. Price available at the fair office or at the door is $25 per person. ticketsoregon.com. General Tickets include wine tasting seating is free with admission and sandwiches. to the fairgrounds. Information: 541-672-8060 Admission is $9 for adults or 13 years and older, $7 for sen- www.pyreneesvineyard.com. -

Moral Disengagement and Lawyers: Codes, Ethics, Conscience, and Some Great Movies

Duquesne Law Review Volume 37 Number 4 Article 4 1999 Moral Disengagement and Lawyers: Codes, Ethics, Conscience, and Some Great Movies Marianne M. Jennings Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/dlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Marianne M. Jennings, Moral Disengagement and Lawyers: Codes, Ethics, Conscience, and Some Great Movies, 37 Duq. L. Rev. 573 (1999). Available at: https://dsc.duq.edu/dlr/vol37/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Duquesne Law Review by an authorized editor of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. Moral Disengagement and Lawyers: Codes, Ethics, Conscience, and Some Great Movies Marianne M Jennings* "The prosecution is not going to get him because I am. My client is guilty and he deserves to go to jail."' The quote is from the opening statement of lawyer Arthur Kirkland, an ethically troubled soul, in the film And Justice for All. Kirkland/Pacino was not ethically troubled in the sense of disciplinary rule ("DR") violations;2 he was having trouble with the notion of moral disengagement. 3 Pacino had fairly solid evidence that the defendant he was representing in the case was indeed guilty.4 But Pacino was pressured5 into representing a guilty and * The author is Professor of Legal and Ethical Studies and Director of the Joan and David Lincoln Center for Applied Ethics, at the College of Business, Arizona State University, in Tempe, Arizona The author is grateful for the assistance of Martin Karpuk in the research for this article. -

Movies on Reserve

Movies on Reserve List updated January 30, 2015 Movies can be checked out for 3 days at a time. IF THERE IS NO CALL NUMBER, THE MOVIE IS ON ORDER. Call # Title Format PN 1992.77 A13 2010 24 (Seasons 1-8; Bonus disc) PN 1992.77 A13 2010 24 Redemption PN 1997 .A273 2012 Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter PN 1997 .A27 1997 Absence of Malice PN 1997 .A276 2010 Absolute Power PN 1997 .A22 1988a The Accused PN 1997 .A33 2000 Adam’s Rib PN 1997 .A34 2001 The Age of Innocence PN 1997 .A42 2002 Ali PN 1997 .A43 1999 Alice in Wonderland PN 1997 .A35 2006 All the King’s Men PN 1997 .A44 1976a All the President’s Men PN 1997 .A45 1999 Ally McBeal PN 1997 .A43 2007 Amazing Grace PN 1997 .A4545 2008 American Gangster PN 1997 .A455 2000 American Tragedy PN 1997 .A456 1999 Amistad PN 1997.A527 1959a Anatomy of a Murder PN 1997 .A52 2004 And Justice for All PN 1997 .A53 2003 The Andersonville Trial PN 1997 .A54 2000 Angel on My Shoulder PN 1997 .A56 2002 Another Stakeout PN 1997 .A73 2012 Arbitrage PN 1997 .A74 2013 Argo PN 1997 .A75 1999 Arlington Road PN 1997 .A773 2008 The Assassination of Jesse James PN 1997 .A86 2008 Atonement PN 1997 .A95 2005 The Aviator PN 1997 .B215 2001 Babette’s Feast PN 1997.B335 2009 Bad Lieutenant PN 1997 .B33 2010 Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans PN 1997 .B36 2008 Bamako PN 1997 .B365 2000 Bananas PN 1997 .B367 1994a Bandit Queen PN 1997 .B38 2004 Battle of Algiers PN 1997 .B44 2008 Bee Movie PN 1997 .B45 2002 Beijing Bicycle PN 1997 .B475 2001 Best in Show PN 1997 .B478 1964a The Best Man 2 PN 1997 .B497 2008 Beyond -

Grand Jury Under Attack, The--Part I Richard D

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 46 | Issue 1 Article 4 1955 Grand Jury Under Attack, The--Part I Richard D. Younger Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Richard D. Younger, Grand Jury Under Attack, The--Part I, 46 J. Crim. L. Criminology & Police Sci. 26 (1955-1956) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE GRAND JURY UNDER ATTACK f3 Part One RICHARD D. YOUNGER The author is Assistant Professor of History in the University of Houston, Texas. He was formerly Instructor in the Milwaukee Extension Division of the University of Wis- consin. His interest in the Grand Jury began when he was a student in law in the Uni- versity. What intrigued him particularly was the question why about one half of our states have abandoned it. The article following is an abbreviation of Dr. Younger's doctor's thesis entitled A History of the Grand Jury in the United States which he pre- sented to the University of Wisconsin in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Part three under this title, the final portion of Professor Younger's contribution, will be published in our next number.-EDITOR a. As Justice James Wilson took his place at the front of the hall of the Philadelphia Academy, he was clearly pleased to see that so many cabinet officers, members of Congress, and leaders of Philadelphia society had braved the winter weather to attend his weekly law lecture. -

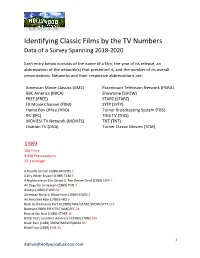

Identifying Classic Films by the TV Numbers Data of a Survey Spanning 2018-2020

Identifying Classic Films by the TV Numbers Data of a Survey Spanning 2018-2020 Each entry below consists of the name of a film, the year of its release, an abbreviation of the network(s) that presented it, and the number of its overall presentations. Networks and their respective abbreviations are: American Movie Classics (AMC) Paramount Television Network (PARA) BBC America (BBCA) Showtime (SHOW) FREE (FREE) STARZ (STARZ) FX Movie Channel (FXM) SYFY (SYFY) Home Box Office (HBO) Turner Broadcasting System (TBS) IFC (IFC) THIS TV (THIS) MOVIES! TV Network (MOVIES) TNT (TNT) Ovation TV (OVA) Turner Classic Movies (TCM) 1989 150 Films 4,958 Presentations 33,1 Average A Deadly Silence (1989) MOVIES 1 A Dry White Season (1989) TCM 4 A Nightmare on Elm Street 5: The Dream Child (1989) SYFY 7 All Dogs Go to Heaven (1989) THIS 7 Always (1989) STARZ 69 American Ninja 3: Blood Hunt (1989) STARZ 2 An Innocent Man (1989) HBO 5 Back to the Future Part II (1989) MAX/STARZ/SHOW/SYFY 272 Batman (1989) SYFY/TNT/AMC/IFC 24 Best of the Best (1989) STARZ 16 Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989) STARZ 140 Black Rain (1989) SHOW/MOVIES/MAX 85 Blind Fury (1989) THIS 15 1 [email protected] Born on the Fourth of July (1989) MAX/BBCA/OVA/STARZ/HBO 201 Breaking In (1989) THIS 5 Brewster’s Millions (1989) STARZ 2 Bridge to Silence (1989) THIS 9 Cabin Fever (1989) MAX 2 Casualties of War (1989) SHOW 3 Chances Are (1989) MOVIES 9 Chattahoochi (1989) THIS 9 Cheetah (1989) TCM 1 Cinema Paradise (1989) MAX 3 Coal Miner’s Daughter (1989) STARZ 1 Collision -

Ordeal by Trial: Judicial References to the Nightmare World of Franz Kafka

The University of New Hampshire Law Review Volume 3 Number 2 Pierce Law Review Article 6 May 2005 Ordeal by Trial: Judicial References to the Nightmare World of Franz Kafka Parker B. Potter Jr. Law clerk to the Hon. Steven J. McAuliffe, Chief Judge, United States DistrictJudge for the District of New Hampshire; Adjunct Professor, University of New Hampshire School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/unh_lr Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Law Commons Repository Citation Parker B. Potter, J. , Ordeal by Trial: Judicial References to the Nightmare World of Franz Kafka, 3 Pierce L. Rev. 195 (2005), available at http://scholars.unh.edu/unh_lr/vol3/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce School of Law at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The University of New Hampshire Law Review by an authorized editor of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. File: Potter-Macroed Created on: 4/26/2005 12:02:00 PM Last Printed: 5/18/2005 10:50:00 AM Ordeal by Trial: Judicial References to the Nightmare World of Franz Kafka PARKER B. POTTER, JR.∗ Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial is firmly entrenched in the modern con- sciousness as an exemplar of judicial indifference to the most basic rights of citizens to understand the nature of criminal proceedings directed against them. Yet, Kafka was not mentioned in an American judicial opin- ion until forty years after his death in 1924.