Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PEDAGOGY and ETHICS of IMPROVISATION USING the HAROLD David Dellus Patton Virginia Commonwealth University

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2007 THE PEDAGOGY AND ETHICS OF IMPROVISATION USING THE HAROLD David Dellus Patton Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons © The Author Downloaded from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/906 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © David Patton 2007 All Rights Reserved THE PEDAGOGY AND ETHICS OF IMPROVISATION USING THE HAROLD A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. by DAVID PATTON Bachelor of Arts, College of William and Mary 1997 Master of Divinity, Union Theological Seminary and PSCE 2005 Director: AARON ANDERSON ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF THEATRE Reader: JANET RODGERS HEAD OF PERFORMANCE Reader: CHARNA HALPERN ARTISTIC DIRECTOR OF IO CHICAGO Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May, 2007 ii Acknowledgement I would like to thank my father for inspiring my love of theatre and supporting me no matter what. I would also like to thank my Aunt Jane and Uncle Norman for being so very cool. Thanks to my old friends, Matt Williams and Tina Medlin Nelson, and my new VCU friends, Shanea N. Taylor and Kim Parkins, for making grad school bearable. Also thanks to Hana, Tara and the whole Beatty family for their love and support. -

Jokes So Effective

CHAPTER TWO But Seriously, Folks ... One of the biggest mistakes an improviser can make is attempting to be funny. In fact, if an audience senses that any performer is deliberately trying to be funny, that performer may have made his task more difficult (this isn't always the case for an established comedian playing before a sympathetic crowd — comics like Jack Benny and Red Skelton were notorious for breaking up during their sketches, and their audiences didn't seem to mind it a bit. A novice performer isn't usually as lucky, unless he's managed to win the crowd over to his side). When an actor gives the unspoken message "Watch this, folks, it's really going to be funny," the audience often reads this as "This is going to be so funny, I'm going to make you laugh whether you want to or not." Human nature being what it is, many audience members respond to this challenge with "Oh, yeah? Just go ahead and try, because I'm not laughing," to the performer's horror. A much easier approach for improvisers is to be sincere and honest, drawing the audience into the scene rather than reaching out and trying to pull them along. Improvisers can be relaxed and natural, knowing that if they are sincere, the audience will be more receptive to them. Audience members laugh at things they can relate to, but they cannot empathize if the performers are insincere. Ars est celare artem, as the ancient Romans would say: the art is in concealing the art. -

Download Master List

Code Title Poem Poet Read by Does Note the CD Contain AIK Conrad Aiken Reading s N The Blues of Ruby Matrix Conrad Aiken Conrad Aiken Time in the Rock (selections) Conrad Aiken Conrad Aiken A Letter from Li Po Conrad Aiken Conrad Aiken BEA(1) The Beat Generation (Vol. 1) Y San Francisco Scene (The Beat Generation) Jack Kerouac Jack Kerouac The Beat Generation (McFadden & Dor) Bob McFadden Bob McFadden Footloose in Greenwich Village Blues Montage Langston Hughes Langston Hughes / Leonard Feather Manhattan Fable Babs Gonzales Babs Gonzales Reaching Into it Ken Nordine Ken Nordine Parker's Mood King Pleasure King Pleasure Route 66 Theme Nelson Riddle Nelson Riddle Diamonds on My Windshield Tom Waits Tom Waits Naked Lunch (Excerpt) William Burroughs William Burroughs Bernie's Tune Lee Konitz Lee Konitz Like Rumpelstiltskin Don Morrow Don Morrow OOP-POP-A-DA Dizzy Gillespie Dizzy Gillespie Basic Hip (01:13) Del Close and John Del Close / John Brent Brent Christopher Columbus Digs the Jive John Drew Barrymore John Drew Barrymore The Clown (with Jean Shepherd) Charles Mingus Charles Mingus The Murder of the Two Men… Kenneth Patchen Kenneth Patchen BEA(2) The Beat Generation (Vol.2) Y The Hip Gahn (06:11) Lord Buckley Lord Buckley Twisted (02:16) Lambert, Hendricks & Lambert, Hendricks & Ross Ross Yip Roc Heresy (02:31) Slim Gaillard & His Slim Gaillard & His Middle Middle Europeans Europeans HA (02:48) Charlie Ventura & His Charlie Ventura & His Orchestra Orchestra Pull My Daisy (04:31) David Amram Quintet David Amram Quintet with with Lynn Sheffield Lynn Sheffield October in the Railroad Earth (07:08) Jack Kerouac Jack Kerouac / Steve Allen The Cool Rebellion (20:15) Howard K. -

Freshman Press Students Support Proposed Bar and Grill ANDREW SCHEINMAN & PENG SHAO NEWS REPORTERS

CAMPUS PHOTOS 8 PAGE HIDDEN GEMS 3 SCENE, PAGE WU FOOTBALL 5 SPORTS, PAGE Freshman Press Students support proposed Bar and Grill ANDREW SCHEINMAN & PENG SHAO NEWS REPORTERS Students may now have a place to enjoy late night programming and deep fried food on campus. This summer, Student Union proposed adding a bar and grill in the basement of Umrath Hall, where Subway used to reside. “Students approached us last year about getting a bar on campus,” Student Union President Morgan DeBaun said. Over the summer, a survey was sent to students and received overwhelming support, with 97 percent of over 1100 students responding positively. This nearly unanimous response convinced the administration to negotiate the project. “The numbers were impressive,” said Steve Hoffner, associate vice chancellor for operations. At the moment, the project is still in its infancy. DeBaun, Hoffner PHOTOS BY NNEKA ONWUZURIKE | STUDENT LIFE and Nadeem Siddiqui, the resident The new South 40 Dining Center offers several district manager of Bon Appétit, are still comfortable chairs around a fireplace. The new anticipating further development but are Bear’s Den was finished was over the summer waiting for a completed design of the and offers many different dining options such as pizza and the new Indian station. space. The proposal outlines a late night bar and grill managed by both the Student Union and Bon Appétit, with a unique Revamped Bear’s Den provides menu and nightly programming, such as musical guests. According to the Student Union survey, students would prefer a new dining location that offers authentic grill more choices for student dining food, such as hamburgers, chicken wings, and deep fried food. -

Beatnik Fashion

Greater Bay Area Costumers Guild Volume 12, Number 5 September-October 2014 Beatnik Fashion Not every member of the Beat Generation wore a beret BY KALI PAPPAS s any fan of the Beat Generation writers will tell The Beatnik. When most people hear the word “beatnik,” you, there’s a chasmic difference between the they probably imagine bored-looking bohemian gals in A beret-wearing, bongo-beating “beatnik” of berets and guys in turtlenecks and weird little goatees. These popular imagination and the people who created stereotypes are rooted in truth, but like the term “beatnik” and lived the Beat philosophy in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s. In itself, they’re not really very representative of the movement defined by the “Beat Generation” nor the people inspired by its counterculture philosophy. The reality is that the intellectuals, artists, and anti- bourgeois iconoclasts of mid-twentieth century America dressed a lot like everyone else. Legendary San Fig. 1: Spoofing beatnik stereotypes Fig. 2: Jack Kerouac Francisco columnist Herb Caen created the anticipation of our “On the Road” event in November, I’ve term “beatnik” in 1958, a portmanteau of “beat” and compiled a short list of looks - for both men and women - that “Sputnik” (as in the Soviet satellite) that - in conjunction combine standard 1950s fashions with enough bohemian with a short report about freeloading hep cats helping sensibility to help you fit in without looking like a stereotype themselves to booze at a magazine party - was meant to (unless you really want to). poke fun at common perceptions of the counterculture. -

Funny Feminism: Reading the Texts and Performances of Viola

FUNNY FEMINISM: READING THE TEXTS AND PERFORMANCES OF VIOLA SPOLIN, TINA FEY AND AMY POEHLER, AND AMY SCHUMER A Thesis by LYDIA KATHLEEN ABELL Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Chair of Committee, Kirsten Pullen Committee Members, James Ball Kristan Poirot Head of Department, Donnalee Dox May 2016 Major Subject: Performance Studies Copyright 2016 Lydia Kathleen Abell ABSTRACT This study examines the feminism of Viola Spolin, Tina Fey and Amy Poehler, and Amy Schumer, all of whom, in some capacity, are involved in the contemporary practice and performance of feminist comedy. Using various feminist texts as tools, the author contextually and theoretically situates the women within particular feminist ideologies, reading their texts, representations, and performances as nuanced feminist assertions. Building upon her own experiences and sensations of being a fan, the author theorizes these comedic practitioners in relation to their audiences, their fans, influencing the ways in which young feminist relate to themselves, each other, their mentors, and their role models. Their articulations, in other words, affect the ways feminism is contemporarily conceived, and sometimes, humorously and contentiously advocated. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would briefly like to thank my family, especially my mother for her unwavering support during this difficult and stressful process. Her encouragement and happiness, as always, makes everything worth doing. I would also like to thank Paul Mindup for allowing me to talk through my entire thesis with him over the phone; somehow you listening diligently and silently on the other end of the line helped everything fall into place. -

The Second City: Notes on Chicago's Funny Urbanism

The Second City: Notes on Chicago’s Funny Urbanism The story is of how the city of Chicago provided the ground for the development of a style of improvisational comedy, making it a setting, but also a seedbed; the fertile ground for a creative explosion. This is an urban study as cultural history, and also as performance. JOHN MCMORROUGH Cities are funny things, both equation and caprice, they are testaments to, and University of Michigan limit cases of, “big plans,” and nowhere more so than Chicago. Chicago is the Magnificent Mile, the South Side, and the Loop; it is also the ‘Windy City,’ the JULIA MCMORROUGH ‘City of Broad Shoulders,’ and the ‘Second City.’ “Come and show me another city University of Michigan with lifted head singing so proud to be alive and coarse and strong and cunning.” Published one hundred years ago, this line from Carl Sandburg’s seminal poem “Chicago” speaks to the unique character of the city, borne of equal parts opti- mism and effort. Chicago, like all cities, is a combination of circumstantial facts (the quantities and dispositions of its urban form) and a projective imagination (how it is seen and understood). In Chicago these combinations have been par- ticularly colored by the city’s status as an economic capital; its history is one of money and power, its form one of hyperbolic extrapolation. Whether revers- ing the flow of the Chicago River in 1900, or raising the mean level of the city by physically lifting buildings six feet in the 1850s, Chicago’s answer to the question of what the city is, has always been, in a manner of speaking, funny (both peculiar and amusing). -

Rhetorical Ripples: the Church of the Subgenius, Kenneth Burke & Comic, Symbolic Tinkering

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2014 Rhetorical Ripples: The hC urch of the SubGenius, Kenneth Burke & Comic, Symbolic Tinkering Lee A. Carleton Virginia Commonwealth University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Discourse and Text Linguistics Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, New Religious Movements Commons, and the Rhetoric and Composition Commons © The Author Downloaded from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/3667 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rhetorical Ripples: The Church of the SubGenius, Kenneth Burke & Comic, Symbolic Tinkering A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Media, Art and Text Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University by Lee Allen Carleton B.S. Bible, Lancaster Bible College, 1984 M.A. English Composition, Virginia Commonwealth University, 1996 Director: Dr. Nicholas Sharp Assistant Professor English Department Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia November 2014 ii Dedication This work is dedicated to my wife Clary, my son Holden (6) and my daughter Huxley (3) who have inspired my ongoing efforts and whose natural joy, good humor and insight lit my wandering path. On the eve of my 53rd birthday, I can honestly say that I am a very fortunate and happy man. Acknowledgements Without a doubt, these few words can hardly express the gratitude I feel for my committee and their longsuffering patience with me as I finally found my focus. -

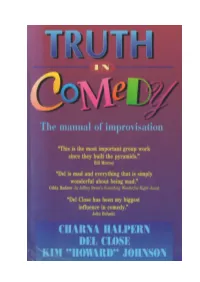

Improv Nerd with Jimmy Carrane Welcomes Special Guest Charna Halpern at Four Star Comedy Fest at Navy Pier

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: September 24, 2012 Nick Shields, Navy Pier 312-595-5136 [email protected] Lauren M. Heist 847-868-3653 [email protected] Improv Nerd with Jimmy Carrane welcomes special guest Charna Halpern at Four Star Comedy Fest at Navy Pier CHICAGO — Navy Pier, Inc. is excited to announce that iO Chicago founder Charna Halpern will be the guest of honor at a special performance of Improv Nerd at the inaugural Four Star Comedy Fest at Navy Pier! On Saturday, Oct. 6 at 5 p.m., host Jimmy Carrane will interview Halpern about her legendary life during a live taping of Improv Nerd, a popular podcast that gives audiences a behind-the-scenes look at careers in comedy. Tickets to Improv Nerd are free. Born in 1952, Halpern co-founded the iO with Del Close in 1984 and has launched the careers of such famous comedians as Mike Myers, Chris Farley, David Koechner, Adam McKay, Tina Fey and many more. She is the co-author of Truth in Comedy and the author of Group Improvisation and Art by Committee. “Charna is one of the most important figures in comedy today, and I think audiences are going to be fascinated with the anecdotes and history she’ll be able to give about so many celebrities,” Carrane says. “It’s going to be a great show!” The live Improv Nerd taping is just one of many events taking place on Oct. 6 as part of the Four Star Comedy Fest. From 1 p.m. – 4 p.m., attendees will have the chance to participate in free workshops for the entire family taught by some of Chicago’s most well-respected improv training centers including The Annoyance Theater, ComedySportz and iO. -

Truth in Comedy.Pdf

Meriwether Publishing Ltd., Publisher P.O. Box 7710 Colorado Springs, CO 80933 Editor: Arthur L. Zapel Typesetting: Sharon E. Garlock Cover design: Tom Myers © Copyright MCMXCIV Meriwether Publishing Ltd. Printed in the United States of America First Edition All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without permission of the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Halpern, Charna, 1952- Truth in Comedy : the manual for improvisation / by Charna Halpern, Del Close, and Kim "Howard" Johnson. - 1st ed. p. cm. ISBN 1-56608-003-7 1. Improvisation (Acting) 2. Stand-up comedy. I. Close, Del, 1934-1999. II. Johnson, Kim, 1955- . III. Title. PN2071.I5H26 1993 792\028-dc20 93-43701 CIP 6 7 8 01 02 03 04 DEDICATIONS Charna Halpern To my loving parents, Jack and Iris Halpern. Without their constant calls to push me to continue writing, this book might never have been finished. I also thank them for raising me in a home that was always filled with laughter. and to Rick Roman — wherever you are. Del Close To Severn Darden, Elaine May and Theodore J. Flicker. Kim "Howard" Johnson To Laurie Bradach, who improvises with me every day, and for the Baron's Barracudas, who blazed the trail. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS So many have been so wonderful. I'd like to send my thanks — To Bill Murray, Mike Myers, George Wendt, Chris Farley, Andy Richter, and Andy Dick for their support — To Suzanne Plunkett, the best photographer in Chicago — To Thorn Bishop for his way with words — To David Shepherd, Paul Sills, and Bill Williams for their inspiration — To Betsy Nolan for being a perfectionist — To "The Family" and all the other ImprovOlympic teams, for helping us to learn from them — Special thanks to Kim Yale — TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword by Mike Myers …………………………………………………. -

August, 2007 19

August, 2007 19 LYRALEN KAYE (AFTRA/SAG) is a Meisner-trained actress who Some people coin the feeling as the "acting bug," but there's nothing buggy received her MFA Theatre from Sarah Lawrence College in 2002. She about it. The word that best describes what JUDITH KALAORA lives for as is seen regularly in Boston theatre and her credits include The Seagull an actress is "rush" - the thrill of adrenaline exploding inside and coming with Theatre Zone, Unveiling with Molasses Tank, Tomboy with J. Rene out of her body thru voice, expression and physicality. Her euphoria? Productions/NYC Fringe Festival, They Named Us Mary with PS Passing that rush to her audience. Judith’s career began at the age of nine. Films/ACP and numerous shows at the Devanaughn Theatre. Her film She was active in community theatre throughout her adolescence, and she credits include 27 Dresses with Columbia Pictures, Mama's Boy with Flancrest Films, and Escape graduated Syracuse University Magna cum Laude, receiving a BFA in from the Night with Smithline Films. Contact Lyralen at [email protected]. Acting and Spanish Literature & Language. She studied at the Shakespeare's Globe in London, and performed the role of Lady Macbeth ROBERT “Big Jake” JACOBS (AEA/SAG) has performed on on the Globe stage. Upon completion of her degree in '05, she returned to Broadway and in Regional and Stock Theatres throughout the East the Boston area and has become extremely involved in the theatre, television and film (feature & Coast; including: Worcester Foothills, Worcester Forum Theatre, Lyric indie) scenes. -

A Look at the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre and Hidden Collections of Improv Comedy

Never Done Before, Never Seen Again: A Look at the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre and Hidden Collections of Improv Comedy By Caroline Roll A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Moving Image Archiving and Preservation Program Department of Cinema Studies New York University May 2017 1 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Chapter 1: A History of Improv Comedy ...……………………………………………………... 5 Chapter 2: Improv in Film and Television ...…………………………………………………… 20 Chapter 3: Case Studies: The Second City, The Groundlings, and iO Chicago ...……………... 28 Chapter 4: Assessment of the UCB Collection ……………..………………………………….. 36 5: Recommendations ………..………………………………………………………………….. 52 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………………………... 57 Bibliography …………………………………………………………………………………… 60 Acknowledgements …...………………………………………………………………………... 64 2 Introduction All forms of live performance have a certain measure of ephemerality, but no form is more fleeting than an improvised performance, which is conceived in the moment and then never performed again. The most popular contemporary form of improvised performance is improv comedy, which maintains a philosophy that is deeply entrenched in the idea that a show only happens once. The history, principles, and techniques of improv are well documented in texts and in moving images. There are guides on how to improvise, articles and books on its development and cultural impact, and footage of comedians discussing improv in interviews and documentaries. Yet recordings of improv performances are much less prevalent, despite the fact that they could have significant educational, historical, or entertainment value. Unfortunately, improv theatres are concentrated in major cities, and people who live outside of those areas lack access to improv shows. This limits the scope for researchers as well.