Closing the Gap: Rights Based Solutions for Tackling Deforestation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dramatic Rise in Killings of Environmental and Land Defenders 1.1.2002–31.12.2013 Deadly Environment Contents

DEADLY ENVIRONMENT THE DRAMATIC RISE IN KILLINGS OF ENVIRONMENTAL AND LAND DEFENDERS 1.1.2002–31.12.2013 DEADLY ENVIRONMENT CONTENTS Executive summary 4 Recommendations 7 Methodology and scope 8 Global findings and analysis 12 Case study: Brazil 18 Case study: Phillipines 20 Conclusion 22 Annex: methodology and scope 23 Endnotes 24 3 The report’s findings and recommendations were noted DEADLY at the summit, with UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay commenting, “It is shocking, but it is not ENVIRONMENT a surprise to me because this is what my own office has been finding in respect of the land claims of indigenous people, not only here in Brazil but elsewhere.”5 THE RISE IN KILLINGS Yet in the month after the Rio summit, 18 environmental OF ENVIRONMENTAL and land defenders were murdered across seven countries. The day the summit closed, two advocates for fishermen’s AND LAND DEFENDERS rights were abducted nearby in Rio de Janeiro state. Almir Nogueira de Amorim and João Luiz Telles Penetra6 7 8 9 were found executed a few days later. They had long campaigned to protect Rio’s fishing communities from the expansion of oil operations. To date, no-one has been held to account for their killings. Executive summary They were just two of 147 known killings of activists in 2012, making it the deadliest year on record to be defend- Never has it been more important to protect the environ- ing rights to land and the environment. ment, and never has it been more deadly. Competition for access to natural resources is intensifying against a back- In December 2014 government officials from around drop of extreme global inequality, while humanity has the world will gather for the next climate change talks already crossed several vital planetary environmental in Lima, Peru. -

Complete Dissertation

VU Research Portal Renewing Destruction: Wind Energy Development in Oaxaca, Mexico Dunlap, A.A. 2017 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Dunlap, A. A. (2017). Renewing Destruction: Wind Energy Development in Oaxaca, Mexico. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 08. Oct. 2021 4 VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT Renewing Destruction: Wind Energy Development in Oaxaca, Mexico ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. V. Subramaniam, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van de promotiecommissie van de Faculteit der Sociale Wetenschappen op donderdag 1 juni 2017 om 11.45 uur in de aula van de universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105 door Alexander Antony Dunlap geboren te Los Angeles 4 promotor: prof.dr. -

State of the World's Indigenous Peoples

5th Volume State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples Photo: Fabian Amaru Muenala Fabian Photo: Rights to Lands, Territories and Resources Acknowledgements The preparation of the State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples: Rights to Lands, Territories and Resources has been a collaborative effort. The Indigenous Peoples and Development Branch/ Secretariat of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues within the Division for Inclusive Social Development of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat oversaw the preparation of the publication. The thematic chapters were written by Mattias Åhrén, Cathal Doyle, Jérémie Gilbert, Naomi Lanoi Leleto, and Prabindra Shakya. Special acknowledge- ment also goes to the editor, Terri Lore, as well as the United Nations Graphic Design Unit of the Department of Global Communications. ST/ESA/375 Department of Economic and Social Affairs Division for Inclusive Social Development Indigenous Peoples and Development Branch/ Secretariat of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues 5TH Volume Rights to Lands, Territories and Resources United Nations New York, 2021 Department of Economic and Social Affairs The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environ- mental data and information on which States Members of the United Nations draw to review common problems and to take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises interested Governments on ways and means of translating policy frameworks developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. -

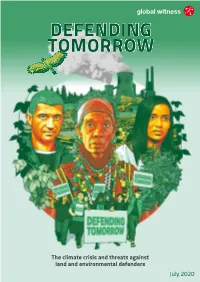

Defending Tomorrow

DEFENDING TOMORROW The climate crisis and threats against land and environmental defenders DEFENDING TOMORROW The climate crisis and threats against land and environmental defendersJuly 20201 Cover image: Benjamin Wachenje / Global Witness DEFENDING TOMORROW The climate crisis and threats against land and environmental defenders Executive summary 6 A global analysis and top findings 8 Defenders: on the frontline of the climate crisis 11 Global map of attacks in 2019 14 Colombia: a rising tide of violence 20 Victories for people – and the planet 24 Philippines: criminalised for protecting the environment 26 Agribusiness: attacks on the rise 30 Romania: corruption and murder in the EU 32 Conclusion: business that costs the earth 35 Recommendations 36 Impacts and achievements of the Defenders’ Campaign 38 Methodology 40 Acknowledgements 42 Endnotes 43 This report, and our campaign, is dedicated to all those EMILIANO CHOCUE, COLOMBIA individuals, communities and organisations that are ENRIQUE GUEJIA MEZA, COLOMBIA bravely taking a stand to defend human rights, their ERIC ESNORALDO VIERA PAZ, COLOMBIA land, and our environment. EUGENIO TENORIO, COLOMBIA 212 of them were murdered last year for doing just that. FERNANDO JARAMILLO, COLOMBIA FREIMAN BAICUÉ, COLOMBIA We remember their names, and celebrate their activism. GERSAÍN YATACUÉ, COLOMBIA GILBERTO DOMICÓ DOMICÓ, COLOMBIA RONALD ACEITUNO ROMERO, BOLIVIA HENRY CAYUY, COLOMBIA ALEXANDRE COELHO FURTADO NETO, BRAZIL HERNÁN ANTONIO BERMÚDEZ ARÉVALO, COLOMBIA ALUCIANO FERREIRA DOS SANTOS, BRAZIL -

Demands for Economic and Environmental Justice

Farmers shout anti-government slogans on a blocked highway during a protest against new farm laws in December 2020 in Delhi, India. Photo by Yawar Nazir/Getty Images 2021 State of Civil Society Report DEMANDS FOR ECONOMIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE Economic and environmental climate mobilisations↗ that marked 2019 and that pushed climate action to the top of the political agenda. But people continued to keep up the momentum justice: protest in a pandemic year by protesting whenever and however they could, using their imaginations In a year dominated by the pandemic, people still protested however and offering a range of creative actions, including distanced, solo and online and whenever possible, because the urgency of the issues continued protests. State support to climate-harming industries during the pandemic and to make protest necessary. Many of the year’s protests came as people plans for post-pandemic recovery that seemed to place faith in carbon-fuelled responded to the impacts of emergency measures on their ability to economic growth further motivated people to take urgent action. meet their essential needs. In country after country, the many people left living precariously and in poverty by the pandemic’s impacts on Wherever there was protest there was backlash. The tactics of repression were economic activity demanded better support from their governments. predictably familiar and similar: security force violence against protesters, Often the pandemic was the context, but it was not the whole story. For arrests, detentions and criminalisation, political vilification of those taking some, economic downturn forced a reckoning with deeply flawed economic part, and attempts to repress expression both online and offline. -

The 'Agora' Is Under Attack: Assessing the Closure Of

IGARAPÉ INSTITUTE a think and do tank SP 49 STRATEGIC PAPER 49 PAPER STRATEGIC 2020 OCTOBER TheThe ‘Agora’‘Agora’ isis underunder attack:attack: Assessing the closure of civic space in Brazil and around the world IGARAPÉ INSTITUTE | STRATEGIC PAPER 49 | OCTOBER 2020 Index Introduction .....................................2 Democratic backsliding .................3 The closure of civic space ...............4 Mapping threats ..............................5 The case of Brazil ..........................11 Fighting back .................................18 Endnotes ........................................20 References for Table 1 ...................25 Cover image: Presentation used by Joice Hasselmann (PSL-SP) at Fake News CPMI, https://noticias.uol.com.br/album/2019/12/04/ apresentacao-usada-por-joice-hasselmann-psl-sp-na-cpmi-das-fake-news.amp.htm?foto=1. IGARAPÉ INSTITUTE | STRATEGIC PAPER 49 | OCTOBER 2020 TheThe ‘Agora’‘Agora’ isis underunder attack:attack: Assessing the closure of civic space in Brazil and around the world 1 THE ‘AGORA’ IS UNDER ATTACK: Assessing the closure of civic space in Brazil and around the world IGARAPÉ INSTITUTE | STRATEGIC PAPER 49 | OCTOBER 2020 Ilona Szabó de Carvalho* But what, exactly, does the closure of civic space mean? What are its implications for democracy more generally? And most importantly, what can civil society groups do Introduction about it? Many countries are experiencing a dramatic closure of civic space. Populist and Civic space is an abstract social science authoritarian governments on the left and construct. It is described by Antoine Buyse as right are increasingly exerting influence over the layer between state, business and family artists, activists, journalists and scholars, in which citizens organize, debate and act.10 demonizing human rights and science, A healthy and open civic space implies that harassing and criminalizing political opponents, groups and individuals within civil society are and implementing repressive legislation to able to organize, participate and communicate chilling effect. -

Hidden Faces of Homelessness: Volume Ii | 1 Introduction

HiddenHidden FacesFaces ofof HomelessnessHomelessness international research on families: volume ii Foreword UNANIMA International is a Coalition of 23 Address Homelessness”, was an achievement for Communities of Women Religious and Friends, in Member States, the United Nations, and Civil 85 Countries with 25,000 Members. We have been Society alike. It was set in the context of declarations advocating on behalf of Women and Children/ and agendas such as the 25th anniversary of the Girls for over 18 years at the United Nations in Copenhagen Declaration on Social Development New York and Geneva. Our mission is to ensure and Program of Action; the General Assembly that the voice and the journey of those who have Resolution 70/1 (2015); the 2030 Agenda for experienced homelessness continues to be heard in Social Development; the Addis Ababa Action places of power. For the past two years our research Agenda of the Third International Conference on on Family Homelessness, Displacement and Trauma Financing for Development; the Sendai Frame- has enabled us to bring the lived experiences of work for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030; and people—especially women and children who have the Agenda 2063 of the African Union. no home— and give them a place at the table, to be heard directly by decision makers. As well as its first 10-year implementation plan, and the New Urban Agenda, the Priority Theme’s In its 75 years of existence, the United Nations had Resolution resulted from a consideration of home- not addressed the issue of homelessness as a prior- lessness within a human rights framework and an ity theme until the 58th Commission on Social examination of its relationship with social protec- Development (CSOCD58) held in February 2020. -

Speak Without Fear

Speak Without Fear The Case for a Stronger U.S. Policy on Human Rights Defenders June 2020 Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 6 Methodology 10 Background: The Impunity Crisis 11 Findings 15 Recommendations 28 Annex 1: Embassy Human Rights Tools 32 Annex 2: Advice for Human Rights Officers 38 About the Authors 41 Endnotes 42 Executive Summary Even before the COVID-19 crisis began, attacks In this report, we call for a more consistent, coordi- against human rights defenders had reached alarm- nated and elevated U.S. State Department response ing levels around the world, especially for those who to these attacks. work on land and environmental issues. The attacks — which include killings and other tactics designed EarthRights International, which works globally to threaten, criminalize and stigmatize — have had a to support land and environmental defenders, has chilling effect on civil society, while allowing powerful prepared this report in conjunction with the Defend- political and economic actors to harm their fellow cit- ing Land and Environmental Defenders Coalition.1 izens with almost total impunity. Governments rarely While our coalition’s goal is to protect those who investigate and prosecute these cases. work on land and environmental issues, many of the threats that we see — and the solutions — apply to The global pandemic has made the situation worse. a broader range of human rights defenders. Accord- In many countries, human rights defenders find ingly, the scope of this report examines U.S. embassy themselves more vulnerable to attacks as they stay support for human rights defenders broadly. at home, unable to vary their movements. -

Enemies of the State?

ENEMIES OF THE STATE? How governments and business silence land and environmental defenders JULY 2019 ENEMIES OF THE STATE? How governments and business silence land and environmental defenders 1 2 ENEMIES OF THE STATE? How governments and business silence land and environmental defenders Executive summary 6 Number of killings per country in 2018 8 Top findings of this report 9 Global map of physical and legal attacks in 2018 10-15 Philippines: The world’s deadliest country 16 Guatemala: A five-fold surge in killings 22 A focus on criminalisation 27 Iran: Crackdown on human rights spreads to environmentalists 30 UK: Draconian jail sentences for anti-fracking protesters 31 Conclusion 34 Recommendations 36 Methodology 38 Acknowledgements 39 This report, and our campaign, is dedicated to all JESÚS ORLANDO GRUESO OBREGÓN, COLOMBIA those individuals, communities and organisations that JHONATAN CUNDUMÍ ANCHINO, COLOMBIA are bravely taking a stand to defend human rights, JOSÉ ABRAHAM GARCÍA, COLOMBIA their land, and our environment. JOSÉ OSVALDO TAQUEZ TAQUEZ, COLOMBIA 164 of them were murdered last year for doing just that. JOSÉ URIEL RODRÍGUEZ, COLOMBIA We remember their names, and celebrate their activism. LUIS ALEXANDER CASTELLANOS TRIANA, COLOMBIA ALUÍSIO SAMPAIO DOS SANTOS, BRAZIL MARÍA DEL CARMEN MORENO PAEZ, COLOMBIA CARLOS ANTÔNIO DOS SANTOS, BRAZIL NIXON MUTIS, COLOMBIA EDEMAR RODRIGUES DA SILVA, BRAZIL ÓLIVER HERRERA CAMACHO, COLOMBIA EDUARDO PEREIRA DOS SANTOS, BRAZIL PLINIO PULGARÍN, COLOMBIA GAZIMIRO SENA PACHECO, BRAZIL RAMÓN -

Daring to Stand up for Human Rights in a Pandemic

DARING TO STAND UP FOR HUMAN RIGHTS IN A PANDEMIC Artwork by Jaskiran K Marway @J.Kiran90 INDEX: ACT 30/2765/2020 AUGUST 2020 LANGUAGE: ENGLISH amnesty.org 1 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 1. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF DEFENDING HUMAN RIGHTS DURING A PANDEMIC 5 2. ATTACKS DURING THE COVID-19 CRISIS 7 2.1 COVID-19, A PRETEXT TO FURTHER ATTACK DEFENDERS AND REDUCE CIVIC SPACE 8 2.2 THE DANGERS OF SPEAKING OUT ON THE RESPONSE TO THE PANDEMIC 10 2.3 DEFENDERS EXCLUDED FROM RELEASE DESPITE COVID-19 – AN ADDED PUNISHMENT 14 2.4 DEFENDERS AT RISK LEFT EXPOSED AND UNPROTECTED 16 2.5 SPECIFIC RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH THE IDENTITY OF DEFENDERS 17 3. RECOMMENDATIONS 20 4. FURTHER DOCUMENTATION 22 INDEX: ACT 30/2765/2020 AUGUST 2020 LANGUAGE: ENGLISH amnesty.org 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The COVID-19 pandemic and states’ response to it have presented an array of new challenges and threats for those who defend human rights. In April 2020, Amnesty International urged states to ensure that human rights defenders are included in their responses to address the pandemic, as they are key actors to guarantee that any measures implemented respect human rights and do not leave anyone behind. The organization also called on all states not to use pandemic-related restrictions as a pretext to further shrink civic space and crackdown on dissent and those who defend human rights, or to suppress relevant information deemed uncomfortable to the government.1 Despite these warnings, and notwithstanding the commitments from the international community over two decades ago to protect and recognise the right to defend human rights,2 Amnesty International has documented with alarm the continued threats and attacks against human rights defenders in the context of the pandemic. -

Defending Tomorrow

DEFENDING TOMORROW The climate crisis and threats against land and environmental defenders DEFENDING TOMORROW The climate crisis and threats against land and environmental defendersJuly 20201 Since the publication of this report new information has come to light resulting on one case from Kazakhstan being removed from our database. Additional information has led to the inclusion of an extra case from Kazakhstan which meets our criteria for inclusion. As such, the figures for 2019 remain 212 killings globally, with no changes to country level or sector statistics. Please contact us at [email protected] if you have any further enquiries on this or the methodology involved. Cover image: Benjamin Wachenje / Global Witness DEFENDING TOMORROW The climate crisis and threats against land and environmental defenders Executive summary 6 A global analysis and top findings 8 Defenders: on the frontline of the climate crisis 11 Global map of attacks in 2019 14 Colombia: a rising tide of violence 20 Victories for people – and the planet 24 Philippines: criminalised for protecting the environment 26 Agribusiness: attacks on the rise 30 Romania: corruption and murder in the EU 32 Conclusion: business that costs the earth 35 Recommendations 36 Impacts and achievements of the Defenders’ Campaign 38 Methodology 40 Acknowledgements 42 Endnotes 43 This report, and our campaign, is dedicated to all those EMILIANO CHOCUE, COLOMBIA individuals, communities and organisations that are ENRIQUE GUEJIA MEZA, COLOMBIA bravely taking a stand to defend human rights, their ERIC ESNORALDO VIERA PAZ, COLOMBIA land, and our environment. EUGENIO TENORIO, COLOMBIA 212 of them were murdered last year for doing just that. -

Land Matters: Dispossession and Resistance November 2015 Poverty Is an Outrage Against Humanity

Land Matters: Dispossession and Resistance November 2015 Poverty is an outrage against humanity. It robs people of dignity, freedom and hope, of power over their own lives. Christian Aid has a vision – an end to poverty – and we believe that vision can become a reality. We urge you to join us. christianaid.ie Lead authors: Sarah Hunt and Karol Balfe. With contributions from Eric Gutierrez, Gaby Drinkwater, William Bell, Julie Mehigan, Hanan Elmasu, Thomas Mortensen, Catalina Ballesteros Rodriguez, Alexia Haywood, Ezekiel Conteh, Kato Lambrechts, Nadia Saracini, Chiara Capraro, Gaby Drinkwater, Roisin Gallagher, Oliver Pierce and Alix Tiernan. With special thanks to Frances Thompson, Robin Palmer, John Reynolds, Shane Darcy, Fionnuala Ni Aolain, Rachel Ibreck and Edward Lahiff. Special thanks also to Mary Kessi, Sinead Coakley, Anna Flaminio and Mara Lilley. Cover photo: In October 2012, 60,000 people, mainly dalits and tribal Indians, started a 300km non-violent land rights march from Gwalior to Delhi. The aim: to ask the Indian government to create and implement a new land reform policy to guarantee access to land and livelihood resources for all, regardless of wealth or caste. 8 days in, the Indian government agreed to the marchers’ demands. The march was organised by Christian Aid partner Ekta Parishad over four years. Photo: Christian Aid / Sarah Filbey Contents 4 Some concepts defined 6 Introduction 6 The focus of this report 8 Why land matters for development 9 Power dynamics and politics 10 Persecution, conflict and violence 11