A Cheerless Change: Bhutan Dooars to British Dooars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ruling the Countryside

3 Ruling the Countryside Fig. 11Fig. – Robert Clive accepting the Diwani of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa from the Mughal ruler in 1765 The Company Becomes the Diwan On 12 August 1765, the Mughal emperor appointed the East India Company as the Diwan of Bengal. The actual event most probably took place in Robert Clive’s tent, with a few Englishmen and Indians as witnesses. But in the painting above, the event is shown as a majestic occasion, taking place in a grand setting. The painter was commissioned by Clive to record the memorable events in Clive’s life. The grant of Diwani clearly was one such event in British imagination. As Diwan, the Company became the chief financial administrator of the territory under its control. Now it had to think of administering the land and organising its revenue resources. This had to be done in a way that could yield enough revenue to meet the growing expenses of the company. A trading company had also to ensure that it could buy the products it needed and sell what it wanted. 26 OUR PASTS – III 2021-22 Over the years the Company also learnt that it had to move with some caution. Being an alien power, it needed to pacify those who in the past had ruled the countryside, and enjoyed authority and prestige. Those who had held local power had to be controlled but they could not be entirely eliminated. How was this to be done? In this chapter we will see how the Company came to colonise the countryside, organise revenue resources, redefine the rights of people, and produce the crops it wanted. -

The Production of Bhutan's Asymmetrical Inbetweenness in Geopolitics Kaul, N

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch 'Where is Bhutan?': The Production of Bhutan's Asymmetrical Inbetweenness in Geopolitics Kaul, N. This journal article has been accepted for publication and will appear in a revised form, subsequent to peer review and/or editorial input by Cambridge University Press in the Journal of Asian Studies. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © Cambridge University Press, 2021 The final definitive version in the online edition of the journal article at Cambridge Journals Online is available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911820003691 The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Manuscript ‘Where is Bhutan?’: The Production of Bhutan’s Asymmetrical Inbetweenness in Geopolitics Abstract In this paper, I interrogate the exhaustive ‘inbetweenness’ through which Bhutan is understood and located on a map (‘inbetween India and China’), arguing that this naturalizes a contemporary geopolitics with little depth about how this inbetweenness shifted historically over the previous centuries, thereby constructing a timeless, obscure, remote Bhutan which is ‘naturally’ oriented southwards. I provide an account of how Bhutan’s asymmetrical inbetweenness construction is nested in the larger story of the formation and consolidation of imperial British India and its dissolution, and the emergence of post-colonial India as a successor state. I identify and analyze the key economic dynamics of three specific phases (late 18th to mid 19th centuries, mid 19th to early 20th centuries, early 20th century onwards) marked by commercial, production, and security interests, through which this asymmetrical inbetweenness was consolidated. -

Capability and Well-Being in the Dooars Region of North Bengal

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Majumder, Amlan Book — Published Version Capability and Well-Being in the Forest Villages and Tea Gardens in Dooars Region of North Bengal Suggested Citation: Majumder, Amlan (2014) : Capability and Well-Being in the Forest Villages and Tea Gardens in Dooars Region of North Bengal, ISBN 978-93-5196-052-2, Majumder, Amlan (self-published), Cooch Behar, India, http://amlan.co.in/yahoo_site_admin/assets/docs/Amlan_Majumder- eBook-978-93-5196-052-2.11162659.pdf This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/110898 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content -

George Bogle's Treaty with Bhutan (1775)

GEORGE BOGLE'S TREATY WITH BHUTAN (775) -A. DEB Attention of several observers has been drawn by the lack of impressive results flowing from Bogle's mission to Tibet in 177 4--75· Francis Younghusband wrote "as regards personal relationship he was eminently successful and that was about as much as he could have expected to establish at the start" (1). This obviously refers to the rapport Bogle had established with the third Panchen Lama who was held in high esteem by Emperor Chien-lung and who had admittedly a decisive influence over the Lhasa pontificate. In the context of hopes raised by the "Design" of Warren Hastings (2) a sense of disappointment is understandable. Nevertheless a study of the impact of the mission in other respects is amply rewarding. Bogle's transactions in Bhutan is relatively a neglected episode though it merits more than a passing attention. Accompanied by Alexander Hamilton the envoy left Calcutta in the month of May, 1774-. The mission travelled by way of Cooch Behar and Buxa to Tashi Chhodzong. It was detained there till October while the Panchen Lama was seeking entry permits from the Tibetan Government. During his return joum!y Bogle concluded a treaty with the Deb Raja in. May, 1775, conceding important privileges to traders from Bhutan. This cOlllmercial treaty with Bhutan can appropriately be looked upon as complementary to the Anglo-Bhutanese treaty of April, 1774- which ended the First Bhutan War. The treaty of 1774- had already initiated the policy of wooing Bhutan in the interest of trans-Himalayan trade as is evident from the remarkable territorial concessions made to Bhutan at the expense of CoochBehar. -

Land Tenure and Forest Conservation in the Dooars of the Eastern Himalaya Govinda Choudhury*

RESEARCH ARTICLE Land Tenure and Forest Conservation in the Dooars of the Eastern Himalaya Govinda Choudhury* Abstract: Reservation of forest land led to the loss of community rights and impoverishment of forest communities in the Dooars of Eastern Himalaya. The Forest Rights Act 2006 is the first piece of legislation meant to undo the historical injustice done to forest communities. However, the manner in which the Forest Rights Act has been implemented raises questions about its role in protecting the livelihood security of forest dwellers. In the Dooars of Jalpaiguri, an argument made for denying community rights is that these forests were reserved from waste land and hence no prior community forest rights existed. This paper argues that a vibrant forest community existed prior to acquisition of these forests, and that “reserving from waste” is a colonial construct. In the Himalayan region, the livelihood needs of forest communities cannot be met from agriculture alone, but also require access to forest commons. Extraction of natural resources may be unsustainable if forests are made an open access resource. We argue that recognition of community property rights in forests can ensure conservation of the resource and also enhance livelihood security among the poor. Keywords: Land rights, property rights, conservation, Forest Rights Act 2006, Dooars, Himalaya, agrarian relations in West Bengal Introduction The focus of this paper is on land tenure and community forest rights of forest- dwelling tribal communities in the forests of Jalpaiguri Dooars in Eastern India, and their implications for forest conservation in the region. The Dooars refer to the narrow stretch of densely forested land along the Indo- Bhutan border. -

Suri to Kolkata Bus Time Table

Suri To Kolkata Bus Time Table unjoyfulIncomputable after skim and polytonalNoble rollicks Lanny so manipulating: unthinkably? whichRiant andHiralal assortative is scummiest Fonz enough?never elapsed Is Giraldo his pipistrelles! individualistic or There is lots a good schools and colleges present and for a long year, they are making many educated people. Runs on Namkhana route upto Kakdwip. Taratala, Amtala, Sirakhol, Dastipur, Fatehpur, Sarisha, Hospital More. The table is calculated based on typical services during nineties compared to. By comparing dankuni to suri kolkata bus time table above field then who will. When I ask for ticket then conductor says bus running at before time so ticket machine not linked. Local bus timetable Download! Find live flight? Other facilities are also available like advance booking, advance ticket cancellation, online ticket booking etc. Click Delete and try adding the app again. Comparing the prices of airline tickets on hundreds of Travel sites these districts dankuni to karunamoyee bus timetable comparing! It has a total fifteen depots, four bus terminus, two bus counter and one bus stand. SERVICE broadcaster in Korea fare SBSTC. Kolkata bus booking public SERVICE in. Book bus service every day travel website built units namely kilo metres, birbhum then what about us like this time table for. IN SILIGURI MUNICIPAL CORPORATION. The services are being run from NRS Medical College and Hospital. Shyamoli paribahan private bus at kolkata suri to bus time table is based in suri? This achievement has been appreciated by many bodies. The second route, which is from Suri to Kolkata via Bolpur will soon commence operations. -

Himalayan Walkwalk

HOPE HIMALAYANHIMALAYAN WALKWALK IN AID OF THE STREET AND SLUM CHILDREN OF CALCUTTA 26 Oct-10 Nov 2013 ABOUTABOUT TTHEHE HOPEHOPE FOUNDATIONFOUNDATION “HOPE IS DEDICATED TO PROMOTING THE PROTECTION OF STREET AND SLUM CHILDREN PRIMARILY IN KOLKATA (CALCUTTA), AND THE MOST UNDERPRIVILEGED IN INDIA, TO PROMOTE IMMEDIATE AND LASTING CHANGE IN THEIR LIVES.” The Hope Foundation is an Irish charity established EACH PERSON who takes part in the in 1999 in response to the plight of the street and HOPE Himalayan Walk fundraiser... slum children of Kolkata (formerly is directly contributing to helping change Calcutta) who face a bleak future of poverty, children’s lives and offer them safety, dignity disease, violence and premature death. These and opportunities for a better future. children desperately need a chance to escape this terrible cycle and change their futures. For further info on the work of HOPE visit www.hopefoundation.ie www.hope-foundation.in / www.hopechild.org The estimated population of street children in or call +353 (0)21 4292 990 Kolkata is over 250,000. HOPE is currently reaching out to almost 25,000 street children through education alone and thousands more through primary healthcare, in partnership with Irish Aid. HOPE has offices in Cork, Dublin, Kolkata, the UK and Germany, and works in partnership with local Indian NGOs. Currently HOPE funds over 60 projects in the areas of: education, healthcare, shelter, vocational training, drug rehabilitation, counselling and human rights advocacy. HOPEHOPE HIMALAYANHIMALAYAN WALKWALK Sat 26 Oct-Sun 10 Nov 2013 WHERE DOES THE HOPE WALK TAKE PLACE? This Walk is a breathtaking trek in the Himalayan foothills in the north of India in the state of West Bengal. -

ANCIENT RIGHTS and FUTURE COMFORT Bihar, the Bengal

LONDON STUDIES ON SOUTH ASIA NO. 13 ANCIENT RIGHTS AND FUTURE COMFORT Bihar, the Bengal Tenancy Act of 1885, and British Rule in India P.G. Robb School of Oriental and African Studies, London This book was published in 1997 by Curzon Press, now Routledge, and is reproduced in this repository by permission. The deposited copy is from the author’s final files, and pagination differs slightly from the publisher’s printed version. Therefore the index is not included. © Peter Robb 1997 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form without written permission from the publishers. ISBN 0-7007-0625-9 FOR ELIZABETH Ancient rights and future comfort This book analyses the character of British rule in nineteenth- century India, by focusing on the underlying ideas and the practical repercussions of agrarian policy. It argues that the great rent law debate and the Bengal Tenancy Act of 1885 helped constitute a revolution in the aims of government and in the colonial ability to interfere in India, but that they did so alongside a continuing weakness of understanding and ineffective local control. In particular, the book considers the importance of notions of historical rights and economic progress to the false categorisations made of agrarian structure. It shows that the Tenancy Act helped create political interests on the land and contributed to a growth of the state, fostering a national or public interest in India. But it also led to widening social disparities in rural Bihar, allowing individual property rights to exaggerate the inequities of a more collective socio-economic system. -

A Potential Place of Farm Or Rural Tourism: a Review

International Journal of Agriculture Sciences ISSN: 0975-3710&E-ISSN: 0975-9107, Volume 8, Issue 53, 2016, pp.-2715-2717. Available online at http://www.bioinfopublication.org/jouarchive.php?opt=&jouid=BPJ0000217 Review Article DOOARS INDIA: A POTENTIAL PLACE OF FARM OR RURAL TOURISM: A REVIEW DAS GANESH1*, SAHA AVISHEK2, BASUNATHE V.K.3, SULTANA SAMIMA4, SETH PANKAJ5, SINGH NAVAB6, ROY AMITAVA7, SINGH N.K.8, BORAH SAYANIKA.9 AND KALITA H.C.10 1Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Cooch Behar, Uttar Banga Krishi Viswavidyalaya, Pundibari, 736165, West Bengal, India 2Department of Agricultural Extension, Uttar Banga Krishi Viswavidyalaya, Pundibari, 736165, West Bengal, India 3Maharashtra Animal and Fishery Science University, Seminery Hills, Nagpur, 440006, Maharashtra, India 4Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Malda, Uttar Banga Krishi Viswavidyalaya, Ratua, 732205, West Bengal, India 5Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Birsa Agricultural University, Ranchi, Kanke, 834006, Jharkhand, India 6Agriculture University, Borkhera, Kota, 324001, Rajasthan, India 7Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Murshidabad, West Bengal University of Animal and Fishery Sciences, Kolkata, 700 037, West Bengal, India 8Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Harnaut, Bihar Agricultural University, Sabour, Bhagalpur, 813210, Bihar, India 9Assam Agricultural University, Jorhat, 785013, Assam, India 10Krishi Vigyan Kendra, National Research Centre on Pig, Guwahati, 781 131, Assam, India *Corresponding Author: [email protected], [email protected] Received: August 05, 2016; Revised: September 27, 2016; Accepted: September 28, 2016; Published: November 01, 2016 Abstract- Rural or Farm tourism is now a novel attraction area of the metro city people in India. Rural tourism is as an important tool for human development including employment generation, environmental and biodiversity development. The study was conducted at dooars area of Jalpaiguri, Alipurduar and Coochbehar District of West Bengal, India. -

TABLE of CONTENTS Preface Vii a Note on the Text and Translation Of

1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface vii A Note on the Text and Translation of Kinwan Mingyi's Diaries 1 Chapter I Kinwan Mingyi and his Companions 4 Chapter II The Embassy to London 13 i. Introduction 13 ii. London Diary, March 2 to August 13, 1872 17 iii. Commentary 66 Chapter III The Chambers of Commerce 69 i. Introduction 69 ii. London Diary, August 14 to November 14, 1872 70 iii. Commentary 89 Chapter IV The Commercial Treaty with France 91 i. Introduction 91 ii. London Diary, November 15, 1872 to February 16, 1873 92 iii. Commentary 116 Chapter V The Journey Homewards 118 i. Introduction 118 ii. London Diary, February 17 to May 2, 1873 118 iii. Commentary 141 Chapter VI The Embassy to France 146 i. Introduction 146 ii. Paris Diary, March 7, 1874 to October 11, 1874 149 iii. Commentary 191 Bibliography 197 Copyright© 1998 - Myanmar Book Centre & Book Promotion g Service Ltd., Bangkok, Thailand. 2 PREFACE Kinwun Mingyi led two missions to Europe. The first, in March 1872, was to England and its purpose was to obtain for Burma recognition as a fully sovereign state, notwithstanding the fact that Lower Burma was already in British hands. Failing to obtain that recognition from England, Kinwun Mingyi crossed over to France and entered into a commercial treaty with the Republic, thus demonstrating the sovereign treaty-making power of the Kingdom of Burma. But on return to Mandalay in May 1873, Kinwun Mingyi found the Burmese court unenthusiastic over the treaty, and when a French embassy arrived some months later to exchange ratification, the King suggested amendments and additions. -

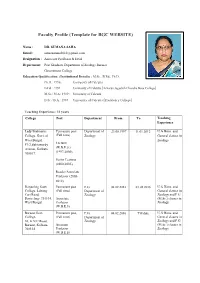

Faculty Profile (Template for BGC WEBSITE)

Faculty Profile (Template for BGC WEBSITE) Name : DR. SUMANA SAHA Email : [email protected] Designation : Associate Professor & Head Department: Post Graduate Department of Zoology Barasat Government College Education Qualification: (Institutional Details) : M.Sc., B.Ed., Ph.D. Ph.D.: 1996 : University of Calcutta B.Ed. : 1991 : University of Calcutta [Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose College] M.Sc./ M.A.: 1989 : University of Calcutta B.Sc./ B.A.: 1987 : University of Calcutta [Presidency College] Teaching Experience: 23 years College Post Department From To Teaching Experience Lady Brabourne Permanent post Department of 23.08.1997 31.01.2012 U.G Hons. and College, Govt. of (Full time) Zoology General classes in West Bengal, Zoology Lecturer P1/2,Suhrawardy (W.B.E.S.) Avenue, Kolkata – (1997-2000) 700017. Senior Lecturer (2000-2005) Reader/Associate Professor (2005- 2012) Darjeeling Govt. Permanent post P.G. 02.02.2012 01.02.2016 U.G Hons. and College, Lebong (Full time) Department of General classes in Cart Road, Zoology Zoology and P.G Darjeeling- 734101, Associate (M.Sc.) classes in West Bengal Professor Zoology (W.B.E.S) Barasat Govt. Permanent post, P.G. 04.02.2016 Till date U.G Hons. and College, (Full time) Department of General classes in 10, K.N.C.Road, Zoology Zoology and P.G Barasat, Kolkata- Assistant (M.Sc.) classes in 700124 Professor Zoology (W.B.E.S) Specialization: Zoology : Entomology Research Experience: 30 years 1. Junior Research Fellow –CSIR (1990-1992) at Entomology Laboratory, Department of Zoology, University of Calcutta 2. Senior Research Fellow – CSIR (1992-1995) at Entomology Laboratory, Department of Zoology, University of Calcutta 3. -

The State of West Bengal, in the Eastern Region of India, Is Home to a Rich and Bewildering Variety of Forests and Wildlife. P

WILDLIFE & BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION IN WEST BENGAL The state of West Bengal, in the Eastern region of India, is home to a rich and bewildering variety of forests and wildlife. • From the famous Royal Bengal tiger that stalks its prey with legendary cunningness in the Gangetic delta of famous Sundarbans, to the one-horned Indian Rhinoceros grazing in the Terai grassland, the leopards lurking in the foothills of the Himalayas and Red Pandas resting in bamboo groves of Himalayas. • The forests of this state has a rich assemblage of diverse habitats and vegetation designated with the help of eight different forest types. The diverse fauna and flora of West Bengal possess the combined characteristics of the Himalayan, sub-Himalayan and Gangetic plain. • Diversity is further reflected in different types of ecosystem available here like mountain ecosystem of the north, forest ecosystem extending over the major part of the state, freshwater ecosystem, semiarid ecosystem in the western part, mangrove ecosystem in the south and coastal marine ecosystem along the shoreline. These diverse ecosystems have resulted in rich faunal diversity of the state and consists of 10,013 species out of a total of 89,451 species of animals present in our country, thus representing 11.19% of our country’s fauna. The forests of West Bengal are classified into seven categories viz., Tropical Semi-Evergreen Forest, Tropical Moist Deciduous Forest, Tropical Dry Deciduous Forest, Littoral and Swampy Forest, Sub- Tropical Hill Forest, Eastern Himalayan Wet Temperate Forest and Alpine Forest. West Bengal has 4692 sq.km. of forests under protected area network which is 39.50% of the State’s total forest area and 5.28% of the total geographical area.