Tribal Development Policy in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NMML OCCASIONAL PAPER HISTORY and SOCIETY New

NMML OCCASIONAL PAPER HISTORY AND SOCIETY New Series 86 Debating Tribe and Nation: Hutton, Thakkar, Ambedkar, and Elwin (1920s-1940s) Saagar Tewari Assistant Professor, Jindal School of Liberal Arts and Humanities, O.P. Jindal Global University, Sonipat, Haryana Nehru Memorial Museum and Library 2017 © Saagar Tewari, 2017 All rights reserved. No portion of the contents may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the author. This Occasional Paper should not be reported as representing the views of the NMML. The views expressed in this Occasional Paper are those of the author(s) and speakers and do not represent those of the NMML or NMML policy, or NMML staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide support to the NMML Society nor are they endorsed by NMML. Occasional Papers describe research by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to further debate. Questions regarding the content of individual Occasional Papers should be directed to the authors. NMML will not be liable for any civil or criminal liability arising out of the statements made herein. Published by Nehru Memorial Museum and Library Teen Murti House New Delhi-110011 e-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-93-84793-012 Debating Tribe and Nation: Hutton, Thakkar, Ambedkar and Elwin (1920s-1940s)1 During the period 1920-1950, an intense debate surrounded the ‘Tribal Question’, the issue of the future of tribal communities in the emergent Indian nation. This paper seeks to situate the debate historically, analysing in particular the arguments made by certain key figures involved in this discourse especially J.H. -

Comm.Ttee on the Welfare of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes

SCTC No. " COMM.TTEE ON THE WELFARE OF SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES (FIFTH LOK SABRA) TWENTY -SIX11I REPORT MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS Central Grants to Voluntary Organisations Eng.led b the Welfare of Scheduled Castes and . Scheduled Tribes. (Presented on 7th May, 1974) --- LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI April I974,'Vaisakha I896 (Saka) .3./. "'3 L Price: Rs. l' 50 LIST OF AUTHORISED AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF LOK SA-BHA SECRETARIAT PUBLICATIONS SI.No. Name of Agent SL No. , Name of Agent At-.'DHRA PRADESH MAHARASHTRA 10. MIs. Sunderdas Gianchand, I. Andhra University General Cooperative 601, Girgaum Road, Stores Ltd., Waltair New Princess Street, (Visakhapatnam). BombaY-2. 2. G. R. Lakahmipaty Chetty-and Sons, II. The International Book House, (Private) Limited, General Merchants and News Agents, 6, Ash Lane, Newpet, Chandragiri, . Mahatma Gandhi Road, Bombay-!. Chittoor District. 12. The International Book'Service, ASSAM Deccan Gymkhana, Poona-4. 13. Charles Lambert & Company, 3. Western Book Depot, Pan Bazar, 10, Mahatma Gandhi Road, Gauhati. Opposite Clock Tower, Fort, Bombay. BIHAR 14. The Current Book House, Maruti Lane, 4. Amar Kitab Ghar, Post Box. 78, Raghunath Dadaji Street, Diagonal Road, Jamshedpur. BombaY-I 5. MIs. Crown Book Depot, Upper 15. Deccan Book Stall, Bazar, Rancili. Fergusson College Road, Poona-4. GUJARAT 16. M & J. Services, Publishers Representatives, Accounts & Law 6. Vijay Stores, Book Sellers, Station Road, Anand. Babri Road, Bombay-IS. MYSORE' 7. The New Order Book Company, Ellis Bridge, 17. People Book House, Ahmedabad-6. Opp, Jaganmohan Palace, Mysore. HARYANA RAJASTHAN 8. M/, .Prabhu Book Service. Ii. Information Centre, Nal Subzi Mandi, Government of Rajasthan, Gurgaon. -

GRO Details (Branches)

GRO Details (Branches) Region Name Type of Branch Branch / HPC Name GRO NAME ADDRESS CONTACT NUMBER Email SBI Life Insurance Company Ltd, Ahmedabad Primary Branch Ahmedabad 5 Mr. Ankit Panchal Office No. 303, Landmark Building, 100 Ft. Road, Anand 079-26934464 [email protected] Nagar, Satelite, Ahmedabad - 380015 SBI Life Insurance Company Ltd, 2Nd Floor, Office No.221 To 223, City Centre (Labha Ahmedabad Primary Branch Surendranagar Mr. Rakesh Zaveri 02752-226022 [email protected] Complex), Oppositem.P. Arts And Science College, Bus Stand, Surendranagar - 363001 SBI Life Insurance Company Ltd, 3Rd Floor, Office No. 302 Ahmedabad Primary Branch Anand Mr. Ajay Prasad And 303,Maruti Skand, Nr. Ioc Petrol Pump, Anand Vidhyanagar 02692-246270/1 [email protected] Road, Anand - 388001 SBI Life Insurance Company Ltd, Poonam Plaza, 3Rd Floor, Part 3 + Wing C, Near Ahmedabad Primary Branch Ahmedabad 4 Mr. Vikas Sharma 9033047072/3 [email protected] Swaminarayan Temple, Rambaug, Maninagar, Ahmedabad - 380028 Mr. Mahendra SBI Life Insurance Company Ltd, 301, 3Rd Floor, Shri Krishna Ahmedabad Primary Branch Jamnagar Avenue, Opp. Town Hall, Jamnagar District, Jamnagar - 361001 9033047968 / 69 [email protected] Dalsaniya SBI Life Insurance Company Ltd, 2Nd Floor, Tulsimilestone Ahmedabad Primary Branch Nadiad Mr. Anil Luhana Complex, Samir Hospital Compound, College Road, Nadia - 387001 0268 - 2526883/916 [email protected] SBI Life Insurance Co Ltd, 4Th Floor, 2/2, Pushpak Arcade, Ahmedabad Primary Branch Ahmedabad 6 Mr. Chirag Oza Near Holly Child School, Opp Hirawadi Brts Bus Stand, 079-22782220 [email protected] Thakkar Bapa Nagar, Ahmedabad - 382350 SBI Life Insurance Company Ltd, Ahmedabad Primary Branch Porbandar Mr. -

1. May the Old Man Live for a Hundred Years1 2. Fragment of Letter to Jivanji D. Desai

1. MAY THE OLD MAN LIVE FOR A HUNDRED YEARS1 [January 18, 1934]2 You would add to the glory of Gujarat and its people by cele- brating the eighty-first birthday of Abbas Saheb. No one can compete with Abbas Saheb in zeal, self-sacrifice and generosity. I came in contact with him during the inquiry regarding the Punjab Martial Law. Knowing that he belonged to the Tyabji family and had been a Congress worker for a long time, I suggested his name for the Committee. Though a staunch Mussalman, he can live with a staunch Hindu like his own bloodbrother. Among such Hindus I am as one of his family. His secrets are not unknown to me. Everyone in his family contributes to the national service according to his or her capacity. May the old man live for a hundred years! [From Gujarati] Gujarati, 28-1-1934 2. FRAGMENT OF LETTER TO JIVANJI D. DESAI January 18, 1934 PS. I was forgetting one thing completely. I cannot give the right decision on the question of closing of the Prakashan Mandir. The matter was discussed in my presence. I had expressed the view that, if some people took up the task of propagating Gandhi literature, we could leave it to them and let those who wished to court arrest do so. We do not wish to stop anyone from courting arrest so that we can carry on the work of publication. But the converse of this also may be worth considering. We can decide about that only after taking into account all the relevant factors. -

Scheduled Castes

Directory of Voluntary Organisations SCHEDULED CASTES 2009 Documentation Centre for Women and Children (DCWC) National Institute of Public Cooperation and Child Development 5, Siri Institutional Area, Hauz Khas, New Delhi – 110016 Number of Copies: 100 Copyright: National Institute of Public Cooperation and Child Development, 2009 Project Team Project In-charge : Mrs. Meenakshi Sood Project Team : Ms. Alpana Kumari Ms. Renu Computer Assistance : Mrs. Sandeepa Jain Mr. Varun Kumar Acknowledgements : Voluntary Organizations NIPCCD Faculty NIPCCD Regional Centres Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment Ministry of Women and Child Development Ministry of Human Resource Development Planning Commission DISCLAIMER All efforts have been made to verify and collate information about organizations included in the Directory. Information has been collected from various sources, namely directories, newsletters, Internet, proforma filled in by organizations, telephonic verification, letterheads, etc. However, NIPCCD does not take any responsibility for any error that may inadvertently have crept in. The address of offices of organizations, telephone numbers, e-mail IDs, activities, etc. change from time to time, hence NIPCCD may not be held liable for any incorrect information included in the Directory. Foreword Voluntary organizations play a very important role in society. Social development has been ranked high on the priority list of Government programmes since Independence, and voluntary organizations have been equal partners in accelerating -

Social Service, Work & Reform

Social Service, Work & Reform Volume III M. K. Gandhi Compiled & Edited by: V. B. Kher First Published: December 1976 Printed and Published by Jitendra T. Desai Navajivan Publishing House Ahmedabad-380 014 INDIA Phone: 079 - 27540635, 27542634 E-mail:[email protected] Website: www.navajivantrust.org Social Service, Work & Reform – Volume III EDITORIAL NOTE "To me political power is not an end but one of the means of enabling people to better their condition in every department of life." Young India, 2-7-1931 "Mere withdrawal of English is not independence. It means the consciousness in the average villager that he is the maker of his own destiny, he is his own legislator through his chosen representatives." Young India, 13-2-1930 When peaceful transfer of power to India was effected in a unique way, hopes were universally aroused that the non-violent revolution initiated by Gandhiji would be carried to its fruition in post-independent India. Three decades is comparatively a short span in a nation's life, but it is sufficiently indicative of the lines on which the country is proceeding. Seen in this light, it is undeniable that the revolution has soured on the way. In independent India the humble villager in the 7,00,000 villages dotting the map of the country was to come into his own. He was to be the maker of his destiny and, in effect, the future of the country. The dung heap in the village was to be transformed into a green common ensuring adequate food, clothing and shelter for its inhabitants. -

UNTOUCHABLE FREEDOM a Social History of a Dalit Community

UNTOUCHABLE FREEDOM UNTOUCHABLE FREEDOM A Social History of a Dalit Community VVVijay Prashad vi / Acknowledgements Contents Introduction of illustrations viii Chapter 1. Mehtars ix Chapter 2. Chuhras 25 Chapter 3. Sweepers 46 Chapter 4. Balmikis 65 Chapter 5. Harijans 112 Chapter 6. Citizens 135 Epilogue 166 Glossary 171 Archival Sources 173 Index 175 List of Illustrations Sweepers Outside the Town Hall 8 Entrance to Valmiki Basti 33 Gandhi in Harijan Colony (Courtesy: Nehru Memorial Museum and Library) 114 Portrait of Bhoop Singh 139 Introduction Being an Indian, I am a partisan, and I am afraid I cannot help taking a partisan view. But I have tried, and I should like you to try to consider these questions as a scientist impartially examining facts, and not as a nationalist out to prove one side of the case. Nationalism is good in its place, but it is an unreliablev friend and vanvunsafe vhistorian. (Jawaharlal Nehru, 14 December 1932).1 In the aftermath of the pogrom against the Sikhs in Delhi (1984), in which 2500 people perished in a few days, reports filled the capital of the assail- ants and their motives. It was clear from the very first that this was no disorganized ‘riot’ and that the organized violence visited upon Sikhs was engineered by the Congress (I) to avenge the assassination of Indira Gandhi. Of the assailants, we only heard rumours, that they came from the outskirts of the city, from those ‘urban villages’ inhabited by Jats and Gujjars as well as dalits (untouchables) resettled there during the Na- tional Emergency (1975–7). -

1. a Case for Fasting 1

1. A CASE FOR FASTING 1 One who describes himself as a Harjian worker writes a long letter of which I give the following substance: With the Chairman of the local Harijan Seva Sangh and a sister I went the other day to a village. We were in a bullock-cart. On the way the Chairman and the sister were engaged in conver-sation exch- anging jokes. The sister seemed to be fatigued and lay in the Chair- man’s lap. This familiarity somewhat startled me. On returning we were to take the train to the city from which we had started. We had to wait for a few hours at the station. The Chairman and the sister occu- pied a bench. I sat on the platform ground. It was a moonlight night. I had a mind to test them, for I thought that there was some-thing wrong with them. I, therefore, pretended that I would sleep and told the Chairman: ‘We have yet to wait for some time. If you don’t mind I would sleep for a while. I am tired. Will you wake me up when the train arrives?’ Hearing this, the Chairman seemed to be delighted over my proposal and he readily permitted me to sleep. I lay down and pretended that I was in deep sleep. In order to make sure that I was asleep he called out. Not having any response from me he felt free to take what liberties he liked with the sister. They quietly went into a cluster of trees near by. -

Gupta/Padel, Pedagogy of Assimilation

Gupta/Padel, Pedagogy of assimilation CONFRONTING A PEDAGOGY OF ASSIMILATION: THE EVOLUTION OF LARGE-SCALE SCHOOLS FOR TRIBAL CHILDREN IN INDIA MALVIKA GUPTA AND FELIX PADEL1 Abstract. The policy of assimilating, ‘mainstreaming’ or ‘de-tribalizing’ indigenous communities by placing their children in boarding schools has been increasingly discredited and abandoned, most publicly throughout North America and Australia since the 1980s and 1990s. In India, this history and its dangers are little known, with relatively little awareness of how they are being replicated among many of India’s tribal communities. Education-induced assimilationism has evolved more slowly in India, but has now reached a larger scale than in any other country, with many similar manifestations to the ‘stolen generations’ model that has created outrage in Australia, Canada, the USA and elsewhere. This article traces the evolution and dangers of this history and the present situation in India. Introduction ‘Assimilation’ encapsulates a policy aim regarding indigenous peoples that has often appeared to many people as reasonable and humane – certainly in contrast to the policy of extermination alongside which it often grew up. It is also connected with nationalist ideologies. Alexis de Tocqueville’s influential study of American democracy argued that ‘the Indian nations of North America are doomed to perish’ in the face of an advancing ‘civilization’ that was inherently democratic and – unlike the example of Spanish imperialism – was managing to annihilate them with ‘respect for the laws of humanity’.2 De Tocqueville visited America during the presidency of Andrew Jackson, whose anti-Indian policy culminated in the Cherokees’ ‘trail of tears’ expulsion from their homeland, and de Tocqueville’s statement that Indian nations were being allowed to perish ‘without shedding blood’ proved to be far from the truth. -

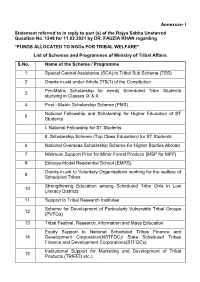

Annexure- I Statement Referred to in Reply to Part (A) of the Rajya Sabha Unstarred Question No

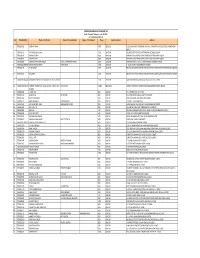

Annexure- I Statement referred to in reply to part (a) of the Rajya Sabha Unstarred Question No. 1248 for 11.02.2021 by DR. FAUZIA KHAN regarding “FUNDS ALLOCATED TO NGOs FOR TRIBAL WELFARE” List of Schemes and Programmes of Ministry of Tribal Affairs S.No. Name of the Scheme / Programme 1 Special Central Assistance (SCA) to Tribal Sub Scheme (TSS) 2 Grants-in-aid under Article 275(1) of the Constitution Pre-Matric Scholarship for needy Scheduled Tribe Students 3 studying in Classes IX & X 4 Post - Matric Scholarship Scheme (PMS) National Fellowship and Scholarship for Higher Education of ST 5 Students I. National Fellowship for ST Students II. Scholarship Scheme (Top Class Education) for ST Students 6 National Overseas Scholarship Scheme for Higher Studies Abroad 7 Minimum Support Price for Minor Forest Produce (MSP for MFP) 8 Eklavya Model Residential School (EMRS) Grants-in-aid to Voluntary Organisations working for the welfare of 9 Scheduled Tribes Strengthening Education among Scheduled Tribe Girls in Low 10 Literacy Districts 11 Support to Tribal Research Institutes Scheme for Development of Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups 12 (PVTGs) 13 Tribal Festival, Research, information and Mass Education Equity Support to National Scheduled Tribes Finance and 14 Development Corporation(NSTFDC)/ State Scheduled Tribes Finance and Development Corporations(STFDCs) Institutional Support for Marketing and Development of Tribal 15 Products (TRIFED etc.) Annexure- II Statement referred to in reply to part (b) & (c) of the Rajya Sabha Unstarred Question No. 1248 for 11.02.2021 by DR. FAUZIA KHAN regarding “FUNDS ALLOCATED TO NGOs FOR TRIBAL WELFARE” STATE-WISE LIST OF VOLUNTARY ORGANISATIONS/NON GOVERNMNENTAL ORGANISATIONS FUNDED DURING 2018-19 TO 2020- 21(as on 31.12.2020) UNDER THE SCHEME OF 'GRANT-IN-AID TO VOLUNTARY ORGANISATION WORKING FOR THE WELFARE OF SCHEDULED TRIBES' (Amount in Rs) 2020-21 Name of the VOs/NGOs with S.No. -

List of Shareholders Whose Final Dividend

TORRENTPHARMACEUTICALSLIMITED Details of Unpaid Dividend as on 01.09.2018 for Final Dividend 2017‐18 Sno Folio/DpidClid Name o f the Holder Name of Second Holder Name of Third Holder Shares Amount Due (Rs.) Address 1 TRE0026719 VIDEHA R SHAH 5600 28000.00 D 502, DHANANJAY TOWER,NR. SHYAMAL CHAR RASTA,SATELLITE ROAD,AHMEDABAD‐ 380015 2 TRE0026716 HASMUKHLAL M SHAH 5600 28000.00 18 LAD SOCIETY OUTSIDE VASTRAPURAHMEDABAD‐380054 3 TRE0036281 HARSHAD DESAI 8000 40000.00 SANJIVANI BLDG PHEROZSHAH STSANTACRUZ WBOMBAY‐400054 4 TRE0038073 PUSHPA DESAI 8000 40000.00 SANJIVANI BLDG PHEROZSHAH STSANTACRUZ WBOMBAY‐400054 5 TRE0005089 KANAYO DWARKADAS AHUJA GOPAL DWARKADAS AHUJA 2400 12000.00 DYNA HOUSE A‐57 STREET 1 MIDC ANDHERI EBOMBAY‐400093 6 IN30018312968815 RAJESH PRASAD MISRA MAYA MISRA 2400 12000.00 E ‐1/ 183 ARERA COLONYBHOPAL‐462016 7 TRE0031464 P VENKATESH 2400 12000.00 SRIVARU SECURITIES PRIVATE LIMITED49 THATHA MUTHIAPPAN STREETMADRAS‐600001 8 TRE0031465 D GANESH 2400 12000.00 SRIVARU SECURITIES PRIVATE LIMITED49 THATHA MUTHIAPPAN STREETMADRAS‐600001 9 IN30045010084885 KOOMBER PROPERTIES & LEASING COMPANY LIMITED 2200 11000.00 CAMELLIA HOUSE14, GURUSADAY ROADCALCUTTA‐700019 10 IN30039418405533 TORRENT PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED ‐ UNCLAIMED SE ACCOUNT 57880 289400.00 TORRENT HOUSEOFF ASHRAM ROADAHMEDABADGUJARAT‐380009 SUSPEN 11 TRE0010943 J K RATHOD 800 4000.00 R F O ATPOST KASA D THANE0 12 TRE0012716 JAGDISH LAL RAJ KUMAR 800 4000.00 42 A EKTA VIHAR AMBALA CANTTHARYANA0 13 TRE0012833 BALVINDER SINGH 400 2000.00 H NO 1365/3 MIG FLAT PHASE‐XI -

PROPOSAL for RURAL AREA Ashram School and Ashram Student’S PURCHASE of ……………………

PROPOSAL FOR RURAL AREA Ashram School and Ashram Student’s PURCHASE OF …………………….. SUBMITTED TO GENERAL MANAGER, GAIL INDIA LTD, BARODA By BHIL SEVA MANDAL Thakker Bapa Road, At & Post DAHOD, Taluka: Dahod Pin: 3890 151 Gujarat State Phone: 02673-246670 Mobile: 9427319500 Email: [email protected] Bhil Seva Mandal, Dahod Project Perposal Report Project Proposal Area District Project Area :- The Dahod and Panchmahal district is one of the most backward and poorest district not only in Gujarat but also perhaps in the country as whole. The extreme poverty and subsequent abnormally havy, our migrations are two major problem of Dahod and Panchmahals district Incidentally, all the villagers in the region have their own land means they are landholders and their condition is worse than other landholders. PROJECT AREA DAHOD DISTICT PANCHMAHALS DISCTRICT Bhil Seva Mandal, Dahod Project Perposal Report Contents Sr No Contents Page No. 1 Project Area 2 Administrative Details 3 Organizational Background 4 Details of Board Members 5 Details of the Proposed Project 6 Competence of the Trust 7 Budget Annexure 9 onawards Bhil Seva Mandal, Dahod Project Perposal Report Administrative Details :- 1. Name and Address : Name : Bhil Seva Mandal, Dahod Address : Thakkar Bapa Road, At & Post DAHOD Tal & Dist : DAHOD Pin : 389 151 Gujarat-India Phon : 02673-246 670 Mobile : 94273 19500 Email : [email protected] 2. Contect Persson : Name :Mr. Narsinhbhai K. Hathila President, Bhil Seva Mandal, Dahod Mobile No. 94273 19500 3. Legal Status : Legal Clearance /Status : 1. Registered under Societies Registration Act 1960 Reg. No 956 Dt. 15.7.1939 2. Registered under Bombay Public Trust Act, 1950 Reg.No.F-6 Panchmahals 3.