Evidence of Predation by Kiore Upon Lizards from The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coastal Resources Limited Marine Dumping Consent Application

Coastal Resources Limited marine dumping consent application Submission Reference no: 78 Izzy Fordham (alternatively Helgard Wagener), Aotea Great Barrier Local Board Submitter Type: Not specified Source: Email Overall Notes: Clause Do you intend to have a spokesperson who will act on your behalf (e.g. a lawyer or professional adviser)? Position Yes Notes The chair of the Aotea Great Barrier Local Board Clause Please list your spokesperson's first name and last name, email address, phone number, and postal address. Notes Izzy Fordham, [email protected], 0212867555, Aotea Great Barrier Local Board, 81 Hector Sanderson Road, Claris, Great Barrier Island Clause Do you wish to speak to your submission at the hearing? Position Yes I/we wish to speak to my/our submission at the hearing Notes Clause If you wish to speak to your submission at the hearing, tick the boxes that apply to you: Position If others make a similar submission I/we will consider presenting a joint case with them at the hearing. Notes Clause We will send you regular updates by email Position I can receive emails and my email address is correct. Notes Clause What decision do you want the EPA to make and why? Provide reasons in the box below. Position Refuse Notes Full submission is attached Coastal Resources Ltd Marine Dumping Consent: Submission by the Aotea Great Barrier Local Board Proposal number: EEZ100015 Executive Summary 1. The submission is made by the Aotea Great Barrier Local Board on behalf of our community, who object to the application. Our island is the closest community to the proposed dump site and the most likely to be affected. -

Atoll Research Bulletin No. 182 the Murine Rodents

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 182 THE MURINE RODENTS RATTUS RATTUS, EXULANS, AND NORVEGICUS AS AVIAN PREDATORS by F. I. Norman Issued by THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Washington, D.C., U.S.A. January 15,1975 Contents Page Introduction 1 References to Predation by Rats 3 Apterygiformes 3 Procellariiformes 3 Pelicaniformes 4 Ciconiiformes 4 Ans eriformes Gallif ormes Charadriiformes Columbiformes Psittaciformes Passeriformes lliscussion References THE MURINE RODENTS RATTUS RATTUS, EXULANS, AND NORVEGICUS AS AVIAN PREDATORS by F. I. Norman-1 / INTRODUCTION Few mammals have adventitiously accompanied man around the world more than members of the Murinae and of these, the most ubiquitous must surely be the --Rattus group. Three species, R. rattus Linn., R. norvegicus Berkenhout, and R. exulans T~eale),have been h~storically associated with-man, and their present distribution reflects such associations. Thus although -R. exulans is generally distributed through the Pacific region, -R. rattus and norvegicus are almost worldwide in distribution, having originated presumably in Asia Minor, as did exulans (walker 1964.). All have invaded, with man's assistance, habitats which previously did not include them, and they have developed varying degrees of commensalism with man. Neither --rattus nor norvegicus has entered antarctic ecosystems, but Law and Burstall (1956) recorded their presence on subantarctic Macquarie Island. Kenyon (1961) and Schiller (1956), however, have shown that norvegicus has become established in the arctic where localised populations are dependent on refuse as a food source during the winter. More frequently, reports bave been made of the over-running of islands by these alien rats. Tristan da Cunha is one such example (Elliott 1957; Holdgate 1960), and Dampier found rattus to be common on Ascension Island in 1701 though presently -norvegicus is more widespread there (nuffey 1964). -

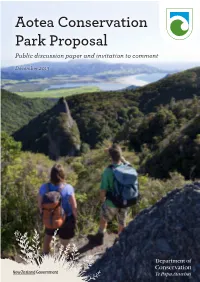

Aotea Conservation Park Proposal Public Discussion Paper and Invitation to Comment

Aotea Conservation Park Proposal Public discussion paper and invitation to comment December 2013 Cover: Trampers taking in the view of Whangapoua beach and estuary from Windy Canyon Track, Aotea/Great Barrier Island. Photo: Andris Apse © Copyright 2013, New Zealand Department of Conservation In the interest of forest conservation, we support paperless electronic publishing. Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 4 2. PROPOSED AOTEA CONSERVATION PARK ................................................................................ 5 2.1 Why is the Department proposing a conservation park? .................................................... 5 2.2 What is a conservation park? ................................................................................................................ 5 2.3 What are the benefits of creating a conservation park? ....................................................... 6 2.4 Proposed boundaries .................................................................................................................................. 6 2.4.1 Map 1: Proposed Aotea Conservation Park ....................................................................... 7 2.4.2 Map 2: Proposed Aotea Conservation Park and other conservation land on Aotea/Great Barrier Island ...................................................................................... 8 2.4.3 Table 1: Land proposed for inclusion in -

Changing Invaders: Trends of Gigantism in Insular Introduced Rats

Environmental Conservation (2018) 45 (3): 203–211 C Foundation for Environmental Conservation 2018 doi:10.1017/S0376892918000085 Changing invaders: trends of gigantism in insular THEMATIC SECTION Humans and Island introduced rats Environments ALEXANDRA A.E. VAN DER GEER∗ Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands Date submitted: 7 November 2017; Date accepted: 20 January 2018; First published online 14 March 2018 SUMMARY within short historical periods (Rowe-Rowe & Crafford 1992; Michaux et al. 2007;Renaudet al. 2013; Lister & Hall 2014). The degree and direction of morphological change in Additionally, invasive species may also alter the evolutionary invasive species with a long history of introduction pathway of native species by mechanisms such as niche are insufficiently known for a larger scale than the displacement, hybridization, introgression and predation (e.g. archipelago or island group. Here, I analyse data for 105 Mooney & Cleland 2001; Stuart 2014; van der Geer et al. island populations of Polynesian rats, Rattus exulans, 2013). The timescale and direction of evolution of invasive covering the entirety of Oceania and Wallacea to test rodents are, however, insufficiently known. Data on how whether body size differs in insular populations and, they evolve in interaction with native species are urgently if so, what biotic and abiotic features are correlated needed with the increasing pace of introductions today due to with it. All insular populations of this rat, except globalized transport: invasive rodent species are estimated to one, exhibit body sizes up to twice the size of their have already colonized more than 80% of the world’s island mainland conspecifics. -

Rattus Exulans) from Fanal Island, New Zealand

Eradication of Pacific rats (Rattus exulans) from Fanal Island, New Zealand. C. R. Veitch Department of Conservation, Private Bag 68-908, Newton, Auckland, New Zealand. Present address: 48 Manse Road. Papakura, New Zealand. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Fanal Island (73 ha) is the largest island in the Mokohinau Group, Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand. Pacific rats, or kiore, (Rattus exulans) reached these islands between about 1100 and 1800 A.D. Pacific rats were removed from all islands in this group, except Fanal Island, in 1990. An aerial application of Talon 7-20 (containing brodifacoum at 20 ppm) at a nominal rate of 10 kg/ha was made on Fanal Island on 4 August 1997 with the intention of eradicating the rats. Despite heavy rainfall immediately after the poisoning operation, and the fact that baits were not of optimum palatability, the rats were eradicated. Keywords Bitrex; brodifacoum; aerial baiting. INTRODUCTION cations they were presumed to be detrimental to natural Fanal Island (Motukino), 73 ha, is the largest and most processes (Holdaway 1989; Atkinson and Moller 1990). southerly island in the Mokohinau Group which is at the Pacific rats were removed from all islands in this group, northern extremity of the Hauraki Gulf, about mid way except Fanal Island, by the Department of Conservation between Great Barrier Island and the mainland (Fig. 1). in 1990 (McFadden and Greene 1994). Fanal Island is part of Mokohinau Islands Nature Reserve, Under the Regulations Act 1936 and the Grey-faced Pet- which is administered by the Department of Conservation rel (Northern Muttonbird) Notice 1979, Ngati Wai of Aotea under the Reserves Act 1977. -

Indirect Effects on Seabirds in Northern North Island POP2017-06

Indirect effects on seabirds in northern North Island POP2017-06 Summarising new information on a range of seabird populations in northern New Zealand June 2019 Prepared by Chris Gaskin, Project Coordinator, Northern New Zealand Seabird Trust (NNZST), Peter Frost, Science Support Service and Megan Friesen (Saint Martin’s University, Lacey, WA, USA/NNZST). Funding support from the and the Birds NZ Research Fund Cover photo (top). Mahuki Island Australasian gannet colony, aerial survey 27 November 2018. Photo: Richard Robinson. Cover photo (bottom). Buller’s shearwater colony on Tawhiti Rahi, Poor Knights Islands. Photo: Chris Gaskin Figure 1 (this page top). Thermal imaging of fluttering shearwaters at the lighthouse, Taranga Hen Island. Screenshot from video: NNZST Figure 2 (this page bottom). Pinnacles and Hanging Rock from the lighthouse, Taranga Hen Island. Photo: Chris Gaskin 2 Introduction This project (POP2017-06) builds on the findings of INT2016-04 (Gaskin 2017). A range of commercial fisheries target aggregations of surface shoaling fish and purse seining is commonly used to capture these fish schools. The dense fish schools create a phenomenon known as fish workups. These fish drive up prey items to the sea surface and observations suggest that this forms an important food source for a range of seabird species. There is currently poor knowledge of both the diet of surface-foraging seabirds and what prey items are being made available to seabirds from fish workups. This has limited our understanding of the mechanisms through which changes in the distribution and/or abundance of fish workups may be driving seabird population changes (population status and annual breeding success). -

Aotea Great Barrier Environmental Trust

Membership Fees Annual Subscriptions: Ordinary: $25, Senior: $20, Family $35, Student $15 Issue 38 Spring/Summer 2017 Life Subscriptions: Life Seniors: $200, Life Ordinary: $250 www.gbiet.org Corporate Subscriptions: Negotiable (contact: [email protected]) NAME: ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. ADDRESS: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… EMAIL: ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. PHONE: ………………………………………………………………………………………………………... CONTACT PREFERENCE (circle): mail/email RESIDENT RATEPAYER RESIDENT AND RATEPAYER MEMBERSHIP TYPE (circle): Ordinary/Senior/Family/Student/Life (senior)/Life SEND TO: Great Barrier Island Environmental Trust, PO Box 35, Okiwi, Great Barrier Island, 0963 DIRECT CREDIT: 12-3110-0058231-00 REFERENCE: Name DID YOU KNOW? You can access back issues of the Environment News (and Bush Telegraph) online at: http://www.gbiet.org/news CONTACT US Email: [email protected] /Facebook and Twitter Readers are welcome to send in contributions to the Environmental News. Email: [email protected] Aotea - Island of Lizards Hauraki Gulf Seabird Research - Claris Fire Scar Little Windy Hill - Conservation Dogs The Needles, the northern-most point on Aotea Great Barrier. Photo: I. Mabey Beyond Barrier GBIET gratefully acknowledges the support of the Great Barrier Local Board. 24 The trees, plants and ground cover had been Pest free sculpted by the movement of a million Four days later, sitting on the back deck of the seabirds, but the most striking feature was that hut and taking the petrel boards off for the last the very island itself – the ground beneath our time, I give a sigh of relief and my partner a feet - was nothing but an enormous labyrinth quick rub for a job well done. No rats. In all of catacombs, excavated by the subterranean honesty, there never usually is on these jobs, movements of a million burrowing seabirds. -

Motokawa, M., Lu, K. and Lin, L. 2001. New Records of the Polynesian Rat

Zoological Studies 40(4): 299-304 (2001) New Records of the Polynesian Rat Rattus exulans (Mammalia: Rodentia) from Taiwan and the Ryukyus Masaharu Motokawa1, Kau-Hung Lu2, Masashi Harada3 and Liang-Kong Lin4,* 1Kyoto University Museum, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan 2Taiwan Agricultural Chemicals and Toxic Substances Research Institute, Wufeng, Taichung, Taiwan 413, R.O.C. 3Laboratory Animal Center, Osaka City University Medical School, Osaka 545-8585, Japan 4Laboratory of Wildlife Ecology, Department of Biology, Tunghai University, Taichung, Taiwan 407, R.O.C. (Accepted June 19, 2001) Masaharu Motokawa, Kau-Hung Lu, Masashi Harada and Liang-Kong Lin (2001) New records of the Polynesian rat Rattus exulans (Mammalia: Rodentia) from Taiwan and the Ryukyus. Zoological Studies 40(4): 299-304. The Polynesian rat Rattus exulans (Mammalia: Rodentia: Muridae) is newly recorded from Taiwan and the Ryukyus on the basis of 3 specimens from the lowland area of Kuanghua, Hualien County, eastern Taiwan, and 2 from Miyakojima Island, the southern Ryukyus. This rat may have been introduced by ships sailing to Taiwan and the Ryukyus from other islands where the species occurs. The morphological identification of R. exulans from young R. rattus is established on the basis of cranial measurements. In R. exulans, two measure- ments (breadth across the 1st upper molar and coronal width of the 1st upper molar) are smaller than corre- sponding values in R. rattus. The alveolar length of the maxillary toothrow is smaller in R. exulans from Taiwan and the Ryukyus than in available conspecific samples from Southeast Asia and other Pacific islands. Thus, this character may be useful in detecting the origin of the northernmost populations of R. -

The Polynesian Rat

Getting To Know … THE POLYNESIAN RAT Drawing of Polynesian Rat. Acknowledgement: Picture taken from “A Field Guide to the Mammals of Borneo”, a publication of Sabah Society and World Wildlife Fund Malaysia. Our rapid urban development has changed the rodent distribution in Singapore. In the past the rodents caught were either the Norway Rat Polynesian Rat, with a damaged tail. (Rattus norvegicus) or the Roof rat (Rattus rattus diiardii). But today with our buildings encroaching into the nature reserves, we are trapping more of the third most common rodent in the The Polynesian rat has become more closely associated with Pacific region, the Polynesian rat(Rattus exulans). It is also humans due to its easy access to food. In the Pacific islands called the Pacific rat or to the Maori, Kiore. where it is resident, it is responsible for the extinction of native birds, insects and also deforestation, by eating the It is smaller and less aggressive than the Norway rat or the stems and nuts of local palms, thus preventing the re-growth Roof rat. With large round eyes, mounted on a pointed snout, of the forest. It has also been associated with the diseases its body is covered with black/brown hair, with a lighter grey leptospirosis and murine typhus. belly and comparatively small, pale feet. The body is thin (weighs up to 80 grams) and the adult measures up to 15 cm Being a poor swimmer, its distribution to the Pacific islands (6 inches) from nose to the base of the tail. The tail is about was helped by the fact that it is considered a delicacy. -

Diversity of Rodents and Treeshrews in Different Habitats in Western Sarawak, Borneo

Malays. Appl. Biol. (2021) 50(1): 221–224 DIVERSITY OF RODENTS AND TREESHREWS IN DIFFERENT HABITATS IN WESTERN SARAWAK, BORNEO SIEU ZHIEN TEO1, YEE LING CHONG2 and ANDREW ALEK TUEN1* 1Institute of Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, 94300 Kota Samarahan, Sarawak, Malaysia 2Department of Science and Environmental Studies, The Education University of Hong Kong, 10 Lo Ping Road, Tai Po, New Territories, Hong Kong *E-mail: [email protected] Accepted 12 March 2021, Published online 15 May 2021 A diverse community of 63 rodent species and nine stopped once the targeted number of 50 or more treeshrew species are found in Borneo (Phillipps & small mammals were caught. These four habitat Phillipps, 2016). They play an important role in types were selected because they are the main providing ecosystem services by contributing to landscape in western Sarawak and have been pollination, seed dispersal, and germination; and subjected to different degrees of disturbance from also food for larger carnivores (Shanahan & a human. Forest sites were categorized as the least Compton, 2000; Morand et al., 2006; Payne & disturbed areas and urban sites as the most Francis, 2007; Phillipps & Phillipps, 2016). Bornean disturbed areas. Trapped rodents and treeshrews tropical forests have been lost, degraded, and were anesthetized using chloroform (Ng et al., 2017). fragmented by anthropogenic activities since the Their morphometric measurements were taken and early 1970s (Bryan et al., 2013; Gaveau et al., 2014), photographed to aid in species identification. The consequently created new or alternative habitats for method of catching rodents and treeshrews generally rodents and treeshrews especially resilient, adaptive, followed that of Aplin et al. -

The Ecology of Rodents in the Tonga Islandsi

Pacific Science (1973), Vol. 27, No.1, p. 92-98 Printed in Great Britain The Ecology of Rodents in the Tonga Islands I JOHN TWIBELL2 THE INFLUENCE on crop damage of Rattus nor shipping came numerous introduced plants and vegicus, Rattus rattus, and the native Polynesian animals. The arrival dates for the common rat, rat, Rattus exulans, was studied during the es Rattus norvegicus, and the "European" roof rat, tablishment of a rat control program for the Rattus rattus, are not known, but are believed Tongan Department of Agriculture in 1969. to be more recent, probably since the increase This was the first long-term study of Tongan of regular shipping trade and the construction rodents. Previous scientific literature on Ton of wharves. gan mammals is very sparse. The Kingdom of Presently rodents account for approximately Tonga, or Friendly Islands, consists ofapproxi 20 percent of the agricultural losses and mately 150 small islands with a combined area $50,000 worth ofeconomic loss each year (Twi of about 256 square miles at lat 21 0 S. The bell, unpublished). This is a conservative esti majority ofthese islands are composed ofraised mate based on damage counts and observation. coral limestone; however, there is a row of six In some areas rats destroy or damage up to volcanic islands on Tonga's western border. 50 percent of the coconuts, which represent the Tongatapu, the location of the government main economic crop in Tonga. center, is the largest and most important island. The following are acknowledged for their The Ha'apai island group lies 80 miles north of greatly appreciated assistance in making this Tongatapu, and 150 miles north is the Vava'u article possible: E. -

Awana Area 9 - Awana

PART 5 - STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT AREAS StrategicStrategic Management Management Area 9 - Awana Area 9 - Awana CITY OF AUCKLAND - DISTRICT PLAN Page 32 HAURAKI GULF ISLANDS SECTION - OPERATIVE 1996 reprinted 1/12/00 PART 5 - STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT AREAS STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT AREA 9 : AWANA • Protection of significant wildlife habitats and 5.9.0 DESCRIPTION ecosystems, particularly those sensitive to disturbance. • Management and control over the location of buildings The Awana SMA is characterised by an enclosed valley and structures in recognition of the propensity of low system opening out to a series of alluvial flats and wetland lying areas to flooding. systems and a sensitive coastal margin comprised of sand • Recognition of high water tables and the limited dunes. A number of smaller bays and headlands along the capability of areas of land for effluent disposal, together rugged coast to the north are also included within the with the consequent implications for development. catchment. Much of the area is in forest or regenerating shrublands with cleared areas in pasture confined to the • Protection of sensitive dune areas and management of foothills and alluvial flats in the lower catchment. A large recreational access and other activities likely to affect portion of the flat land has a high water table and is prone to sand dune stability. flooding. The dunes backing Awana Bay are exposed and • Retention of vegetation and restrictions on land use subject to erosion, while parts of the surrounding hills have activities in upper catchment areas. areas with significant erosion scars. • Management of the sensitive coastal environment. A number of smaller lots exist at the southern end of Awana Bay.